Abstract

Background

Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors have been found to be safe alternatives in adults with cross-intolerant hypersensitivity to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). However they are usually not prescribed in children and there is little information about their tolerance in the pediatric age group.

Objective

This study aims to evaluate the tolerance to etoricoxib in children with hypersensitivity to multiple antipyretics.

Methods

A retrospective case series of children diagnosed with hypersensitivity reactions to NSAIDs and/or paracetamol who underwent a drug provocation test (DPT) with etoricoxib. Information on atopy, family history of allergic diseases, and medication usage was collected. Outcomes of the DPTs and tolerance to etoricoxib were also evaluated.

Results

A total of 24 children, mean age 13.5 years, had a diagnosis of cross-intolerant hypersensitivity to NSAIDs and/or paracetamol. All except one patient successfully tolerated an oral challenge with etoricoxib. Of those who passed the DPT, the majority continued to use etoricoxib with no problems. It was found to be moderately effective in reducing fever and pain.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are widely used for their antipyretic and analgesic properties. They are also frequently involved in hypersensitivity drug reactions [1, 2] and the reported prevalence of NSAID hypersensitivity among children is about 0.3% [3, 4], while NSAIDs account for 24.6% of adverse drug reactions among Singaporean children [5]. Acetylsalicylic acid and other NSAIDs form a group of medications with heterogenic chemical structures whose mechanism of action is the inhibition of prostaglandin production through inhibition of the cyclooxygenase (COX) pathway of arachidonic acid metabolism. This results in shunting towards the 5-lipoxygenase pathway and the increased production of cysteinyl leukotrienes. In general, NSAIDs may cause 2 types of hypersensitivity reactions [6]. The more common type consists of reactions due to the COX-1 inhibitor activity of the drugs, with patients reacting to chemically nonrelated NSAIDs and being classified as cross-intolerant (CI). The second type includes drug-specific, probably immunologically mediated reactions. These patients react to a single drug class of NSAIDs and are considered selective reactors. Several studies have found that most children have CI reactions and that COX-1 inhibition appears to be the main mechanism causing these reactions [7, 8, 9].

Paracetamol is the most commonly used antipyretic medication in children. Although not usually considered an NSAID medication, it is an inhibitor of prostaglandin synthesis. The published incidence of paracetamol cross-reactivity in adults and adolescents with CI NSAID hypersensitivity varies from 4-25% [10, 11, 12].

Patients with a diagnosis of cross-reactive hypersensitivity to NSAIDs and paracetamol are limited in their choice for the treatment of fever and pain. Although selective COX-2 inhibitors were initially developed to reduce the incidence of adverse effects of COX-1 inhibition, many studies have since shown that they may also be safe alternatives in patients with CI NSAID hypersensitivity [13, 14]. Of the coxibs currently in clinical use, etoricoxib exhibits the highest selectivity for COX-2 in vitro [15, 16].

Currently no COX-2 inhibitors are approved for use in children in the United Kingdom, United States or Australia. Despite not being licensed for the pediatric age group, selective COX-2 inhibitors have been used in patients with gastrointestinal comorbidities or severe gastrointestinal intolerance to traditional NSAIDs. A study by Tsoukas et al. [17] evaluated the efficacy and safety of 90-mg etoricoxib once daily versus placebo in the treatment of hemophilic arthropathy. Of the 102 patients recruited in this 6-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 6 were younger than 18 years old. The most common adverse events were upper respiratory tract infections and headache. Intra-articular and gastrointestinal bleeding was attributed to their underlying medical condition. There were no reports of hypersensitivity reactions.

As COX-2 inhibitors are usually not prescribed in children, there is little information about their tolerance in those with hypersensitivity to NSAIDs. Sanchez-Borges et al. [18] studied the tolerance of NSAID-sensitive patients to etoricoxib and of the 58 patients included, 7 children (aged 13-16 years) tolerated an oral challenge with etoricoxib. Recently, Corzo et al. [19] analyzed tolerance to etoricoxib and meloxicam in 41 children aged 9-14 years with NSAID hypersensitivity. Drug provocation test (DPT) with etoricoxib was negative in all patients, suggesting it is a good alternative for treatment in older children with hypersensitivity to NSAIDs.

In our hospital, etoricoxib is only prescribed if other conventional NSAIDs have been proven ineffective or are contraindicated. The dosing regimen as set out in the hospital NSAIDs prescribing protocol states that etoricoxib should only be used in children ≥40 kg and for less than 5 days. Children with cross-reactive hypersensitivity to paracetamol and NSAIDs would be referred to the pediatric allergy clinic where a DPT with etoricoxib would be offered to establish tolerance. This retrospective study aims to analyze tolerance to etoricoxib in this group of patients.

A retrospective case series from the pediatric drug allergy clinic at KK Women's and Children's Hospital (KKH), Singapore. The work was reviewed and approved by the Singhealth Institutional Review Board.

The clinical records of all children diagnosed with hypersensitivity reactions to NSAIDs and paracetamol between January 2011 and December 2013 were analyzed.

Children with suspected hypersensitivity to NSAIDs and paracetamol were evaluated by a pediatric allergist and offered an oral DPT when needed. Information on atopy, family history of allergic diseases and medication usage was recorded in the patient's chart.

Patients were included in the analysis if they had a confirmed hypersensitivity to multiple antipyretics and underwent an oral DPT with etoricoxib. Diagnosis was made either by a clear history of recurrent reactions or by an oral DPT. Atopy was confirmed with skin prick tests with a standard panel of respiratory allergens.

Where the diagnosis could not be convincingly made on history alone, hypersensitivity to NSAIDs and paracetamol was confirmed by performing an oral provocation test in an open procedure. Oral provocation tests were performed according to our previous published protocol [20].

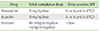

In brief, all tests were performed in the outpatient clinic of KKH. Prior to test administration, patients were interviewed and examined, and vital signs were recorded. All antihistamines were stopped 1 week prior to the test. Increasing doses of the suspected NSAID or paracetamol were administered orally at intervals of 60 minutes up to a total of three administrations in 1 day, depending on the drug (Table 1). Patients were monitored in the clinic for at least 2 hours after the last ingested dose. If cutaneous and/or respiratory symptoms or alterations in vital signs appeared, the procedure was stopped and the symptoms were evaluated and treated. If no symptoms appeared during the oral provocation test, the therapeutic or total cumulative dose was deemed to have been administered successfully.

In cases with confirmed hypersensitivity to NSAIDs and paracetamol, tolerance to etoricoxib was subsequently evaluated.

All tests were performed in the respiratory laboratory by an experienced technician using commercial allergen extracts and the GreerPick skin prick test device (Greer Laboratories, Lenoir, NC, USA), and evaluated by a pediatric allergist. A wheal diameter of 3 mm or more in excess of the negative control was considered a positive test result. The test panel included: house dust mite mix (Dermatophagoides farinae 5,000 AU/mL + Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus 5,000 AU/mL, standardised); Blomia tropicalis 0.2 mg protein/mL, 50% vol/vol glycerol; cockroach mixture (Periplaneta Americana, Blattella germanica); mould mix (Alternaria alternate, Aspergillus fumigatus, Candida albicans, Cladosporium herbarum, Curvularia lunata, Penicillium expansum); cat hair (Felis catus [domesticus] 10,000 BAU (bioequivalent allergy unit)/mL, standardised); dog epithelia (Canis familiaris).

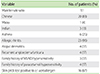

The clinical records of 24 patients, aged 8-18 years (mean, 13.5 years), who underwent a DPT with etoricoxib between January 2011 and December 2013 were analyzed. This group comprised of 12 males (50%), 20 Chinese (83%), 1 Malay (4%), and 3 Indians (13%). Most (96%) had clinically significant atopic disease; 25% had asthma, 96% had allergic rhinitis, and 17% had atopic dermatitis. Recurrent urticaria and/or angioedema were present in 17% of patients while 21% had a positive family history of hypersensitivity to at least one NSAID or paracetamol. Skin prick tests were performed for 16 patients (67%), of which 88% were positive for ≥1 aeroallergen; all of them tested positive for either house dust mites or B. tropicalis. None of the patients had a history of renal or liver disease. The clinical and demographic data for the patients are detailed in Table 2.

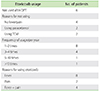

All except 2 patients had a clinical or test proven diagnosis of paracetamol and ibuprofen cross-reactive hypersensitivity (Table 3). Of the remaining 2 patients, one had cross-reactive hypersensitivity to ibuprofen and diclofenac. The other patient had cross-reactive hypersensitivity to paracetamol, diclofenac and aspirin.

A DPT with paracetamol was performed for 6 patients of which 3, after tolerating an oral paracetamol dose of 15 mg/kg of body weight, subsequently developed clinically significant reactions to paracetamol 6 months to 5 years later. These 3 patients were hence diagnosed to have paracetamol hypersensitivity. Among the patients diagnosed with ibuprofen hypersensitivity, 6 were confirmed following a DPT while the rest were diagnosed clinically based on a clear history of repeated reactions to ibuprofen.

Of the 24 patients who underwent a DPT with etoricoxib, all except one successfully tolerated the outpatient oral challenge. The patient who did not pass the challenge was a 15-year-old Chinese female who had allergic rhinitis, recurrent spontaneous urticaria/angioedema, shellfish allergy and sensitization to house dust mites. During the DPT with etoricoxib, the patient developed angioedema and urticaria 8 hours after the last ingested dose. This patient was assessed as having an equivocal challenge result.

Following the DPT with etoricoxib, 20 patients were reviewed in clinic or contacted via telephone while the remaining 4 patients were lost to follow-up. Of the 20 patients, 14 continued to use etoricoxib for fever (57%), pain (14%) or both (29%). The majority took etoricoxib 1-2 times a year and only 1 patient used it >10 times a year (Table 4). Among the 14 patients, 1 complained of intermittent urticaria, sometimes associated with etoricoxib. This was the patient who was assessed as having an equivocal challenge result. When combined with cetirizine, she does not develop urticaria and hence has continued to use etoricoxib for pain relief. All but one patient felt that etoricoxib was effective in reducing fever and pain and would continue using it in the future. Of the 6 patients who did not use etoricoxib after the challenge, 4 cited the reason of no fever for not using the medication. Interestingly, 2 patients returned to using paracetamol at half the therapeutic dose with no problems. Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) was used as an alternative antipyretic for 2 other patients. There were no other adverse reactions reported.

Paracetamol and ibuprofen are widely used as antipyretics among children. Patients with a cross-reactive hypersensitivity to antipyretics, particularly those with reactions to both paracetamol and ibuprofen are limited in their choice for the treatment of fever and pain. In addition, children with early onset NSAID hypersensitivity appear to have a significantly increased likelihood of reacting to paracetamol when compared to children with later onset NSAID hypersensitivity [12]. In particular, Asian children, especially atopic children, seem to be at an increased risk for hypersensitivity reactions to COX-inhibitors [20].

Given that the majority of reactions are due to COX-1 inhibitor activity, drugs that selectively inhibit the COX-2 enzyme may be considered as safe alternatives. However, hypersensitivity reactions to selective COX-2 inhibitors have recently been published, with 6-25% of patients reacting to this group of drugs [21, 22, 23], especially those who do not tolerate paracetamol [13]. Etoricoxib has been found to be a safe alternative for NSAID intolerance in Asian adults although a DPT is still recommended to confirm tolerance [24]. As COX-2 inhibitors are usually not prescribed in children, there are few studies evaluating their use in this population. While it would be hard to justify the routine use of selective COX-2 inhibitors in the pediatric population based on reduction in gastrointestinal adverse effects alone, children with hypersensitivity reactions to multiple antipyretics are limited in their choices of analgesia and antipyretic medication. Recent studies have shown that etoricoxib may be a safe alternative in children >8 years of age [18, 19] and they may benefit from an oral provocation test to confirm tolerance.

Here we have described a series of 24 patients who underwent an oral provocation test with etoricoxib. The majority of patients were adolescents with only 5 being less than 12 years old (range, 8-18 years). All except one patient tolerated the oral challenge and there were no adverse reactions in those who continued to use etoricoxib for fever and pain relief. Even the patient, who initially had an equivocal response during the oral challenge, could subsequently tolerate the full dose.

Clinically significant allergic disease was noted in 96% of patients, with the majority having allergic rhinitis and sensitization to ≥1 aerollergen on skin prick tests. This association of NSAID hypersensitivity with atopy is consistent with previous publications [25, 26], including a previous publication where patients with rhinitis and environmental sensitization were more likely to have greater drug hypersensitivity to antipyretic medications [27]. This is of particular relevance since chronic rhinitis affects 25-42% of the pediatric population in Singapore and allergic rhinitis accounts for two-thirds of these cases [28]. In addition, 21% of our patients had a positive family history of hypersensitivity to at least one NSAID/paracetamol. In a recent study by Yilmaz et al. [29], it was noted that a parental history of NSAID hypersensitivity was the only parameter that increased the odds of a positive NSAID challenge in children. This, together with our findings, suggests there may be a genetic predisposition in NSAID hypersensitivity.

Interestingly, 3 of the patients who initially passed an oral challenge with paracetamol subsequently developed reactions when the same dose was administered during a febrile illness. The appearance of symptoms only in the presence of a fever suggests reduced tolerance to the drug during a febrile illness and that a cofactor may be required for certain reactions to occur or that a possible interaction between the drug and infectious agent is responsible for the symptoms.

Previous adult studies have found that patients who react to paracetamol are more likely to react to a COX-2 inhibitor [30]. It was noted that up to 25% of patients who react to paracetamol also fail to tolerate etoricoxib, compared with 6% who tolerate paracetamol [23]. However in our study, despite 23 of 24 patients having hypersensitivity reactions to both paracetamol and an NSAID, all were found to tolerate etoricoxib. This might be attributed to false positive diagnoses since not all the patients underwent a DPT with the culprit NSAID and paracetamol. In children with a known NSAID hypersensitivity, the risk of reactions to multiple NSAIDs is postulated to increase with time especially if they have concomitant paracetamol hypersensitivity. Hence, children presenting to our hospital with clear histories of recurrent immediate reactions to ≥2 chemically unrelated antipyretics (NSAIDs and/or paracetamol) are offered, for practical purposes, a DPT with etoricoxib.

Among those who continued to use etoricoxib after the DPT, 93% felt that it was moderately effective in reducing fever and pain. However 4 did not use etoricoxib despite passing the challenge as there had been no febrile episodes. A few patients resorted to using TCM and tepid sponging during febrile illnesses while 2 reverted to using paracetamol at half the therapeutic dose. These patients chose not to use etoricoxib because their parents were worried about the potential side effects associated with COX-2 inhibitors. It is also a prescription-only drug, and more expensive than the alternatives. However, when asked if they would consider using etoricoxib in the future, most responded positively and said they would use it as a "last resort".

Considering the lack of antipyretic medications for children with cross-reactive NSAID and paracetamol hypersensitivity, finding a safe alternative is warranted. In our population of children, etoricoxib has been found to be well tolerated, both during the oral challenge test as well as during subsequent use. However we cannot predict if reactions to etoricoxib may appear later in these children and a longer follow-up would be necessary to identify these cases as well as any other long-term side effects. Other limitations of our study include the small study cohort and possible false positive diagnosis in children who did not undergo a DPT with the culprit drug.

In conclusion, etoricoxib can be used as a safe alternative in older children with reactions to multiple antipyretics. Further studies are needed to confirm long-term tolerance and side effects of this drug in adolescents and young adults.

Figures and Tables

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the assistance of the respiratory technologists Tan Soh Gin, Tan Choy Hoon, Lim Mei Lan, Tan Yi Ping, Choo Pui Shan, He Qixian, and Teo Jia Hui Candice.

References

1. Roberts LJ, Morrow JD. Analgesic-antipyretic and antiinflammatory agents and drugs employed in the treatment of gout. In : Hardman JG, Limbird LL, Goodman Gilman A, editors. The pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 10th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill;2001. p. 687–731.

2. Szczeklik A, Nizankowska E, Sanak M. Hypersensitivity to aspirin and non-steroidal antiinflammtory drugs. In : Adkinson NF, Bochner BS, Busse WW, Holgate S, Lemanske RF, Simons FE, editors. Middelton's allergy, principles and practice. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby;2009. p. 1227–1243.

3. Settipane RA, Constantine HP, Settipane GA. Aspirin intolerance and recurrent urticaria in normal adults and children. Epidemiology and review. Allergy. 1980; 35:149–154.

4. Jenkins C, Costello J, Hodge L. Systematic review of prevalence of aspirin induced asthma and its implications for clinical practice. BMJ. 2004; 328:434.

5. Tan VA, Gerez IF, Van Bever HP. Prevalence of drug allergy in Singaporean children. Singapore Med J. 2009; 50:1158–1161.

6. Stevenson DD, Sanchez-Borges M, Szczeklik A. Classification of allergic and pseudoallergic reactions to drugs that inhibit cyclooxygenase enzymes. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2001; 87:177–180.

7. Dona I, Blanca-Lopez N, Torres MJ, Garcia-Campos J, Garcia-Nunez I, Gomez F, Salas M, Rondon C, Canto MG, Blanca M. Drug hypersensitivity reactions: response patterns, drug involved, and temporal variations in a large series of patients. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2012; 22:363–371.

8. Kidon MI, Kang LW, Chin CW, Hoon LS, Hugo VB. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug hypersensitivity in preschool children. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2007; 3:114–122.

9. Zambonino MA, Torres MJ, Munoz C, Requena G, Mayorga C, Posadas T, Urda A, Blanca M, Corzo JL. Drug provocation tests in the diagnosis of hypersensitivity reactions to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2013; 24:151–159.

10. Boussetta K, Ponvert C, Karila C, Bourgeois ML, Blic J, Scheinmann P. Hypersensitivity reactions to paracetamol in children: a study of 25 cases. Allergy. 2005; 60:1174–1177.

11. Pastorello EA, Zara C, Riario-Sforza GG, Pravettoni V, Incorvaia C. Atopy and intolerance of antimicrobial drugs increase the risk of reactions to acetaminophen and nimesulide in patients allergic to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Allergy. 1998; 53:880–884.

12. Kidon MI, Liew WK, Chiang WC, Lim SH, Goh A, Tang JP, Chay OM. Hypersensitivity to paracetamol in Asian children with early onset of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug allergy. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2007; 144:51–56.

13. Woessner KM, Simon RA, Stevenson DD. The safety of celecoxib in patients with aspirin-sensitive asthma. Arthritis Rheum. 2002; 46:2201–2206.

14. Martin-Garcia C, Hinojosa M, Berges P, Camacho E, Garcia-Rodriguez R, Alfaya T, Iscar A. Safety of a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor in patients with aspirin-sensitive asthma. Chest. 2002; 121:1812–1817.

15. Riendeau D, Percival MD, Brideau C, Charleson S, Dube D, Ethier D, Falgueyret JP, Friesen RW, Gordon R, Greig G, Guay J, Mancini J, Ouellet M, Wong E, Xu L, Boyce S, Visco D, Girard Y, Prasit P, Zamboni R, Rodger IW, Gresser M, Ford-Hutchinson AW, Young RN, Chan CC. Etoricoxib (MK-0663): preclinical profile and comparison with other agents that selectively inhibit cyclooxygenase-2. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001; 296:558–566.

16. Tacconelli S, Capone ML, Sciulli MG, Ricciotti E, Patrignani P. The biochemical selectivity of novel COX-2 inhibitors in whole blood assays of COX-isozyme activity. Curr Med Res Opin. 2002; 18:503–511.

17. Tsoukas C, Eyster ME, Shingo S, Mukhopadhyay S, Giallella KM, Curtis SP, Reicin AS, Melian A. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of etoricoxib in the treatment of hemophilic arthropathy. Blood. 2006; 107:1785–1790.

18. Sanchez-Borges M, Caballero-Fonseca F, Capriles-Hulett A. Safety of etoricoxib, a new cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor, in patients with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced urticaria and angioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005; 95:154–158.

19. Corzo JL, Zambonino MA, Munoz C, Mayorga C, Requena G, Urda A, Gallego C, Blanca M, Torres MJ. Tolerance to COX-2 inhibitors in children with hypersensitivity to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Br J Dermatol. 2014; 170:725–729.

20. Kidon MI, Kang LW, Chin CW, Hoon LS, See Y, Goh A, Lin JT, Chay OM. Early presentation with angioedema and urticaria in cross-reactive hypersensitivity to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs among young, Asian, atopic children. Pediatrics. 2005; 116:e675–e680.

21. Weberschock TB, Muller SM, Boehncke S, Boehncke WH. Tolerance to coxibs in patients with intolerance to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): a systematic structured review of the literature. Arch Dermatol Res. 2007; 299:169–175.

22. Dona I, Blanca-Lopez N, Jagemann LR, Torres MJ, Rondon C, Campo P, Gomez AI, Fernandez J, Laguna JJ, Rosado A, Blanca M, Canto G. Response to a selective COX-2 inhibitor in patients with urticaria/angioedema induced by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Allergy. 2011; 66:1428–1433.

23. Asero R, Quaratino D. Cutaneous hypersensitivity to multiple NSAIDs: never take tolerance to selective COX-2 inhibitors (COXIBs) for granted. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013; 45:3–6.

24. Llanora GV, Loo EX, Gerez IF, Cheng YK, Shek LP. Etoricoxib: a safe alternative for NSAID intolerance in Asian patients. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2013; 31:330–333.

25. Sanchez-Borges M, Capriles-Hulett A. Atopy is a risk factor for nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug sensitivity. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000; 84:101–106.

26. Rachelefsky GS, Coulson A, Siegel SC, Stiehm ER. Aspirin intolerance in chronic childhood asthma: detected by oral challenge. Pediatrics. 1975; 56:443–448.

27. Chiang WC, Chen YM, Tan HK, Balakrishnan A, Liew WK, Lim HH, Goh SH, Loh WY, Wong P, Teoh OH, Goh A, Chay OM. Allergic rhinitis and non-allergic rhinitis in children in the tropics: prevalence and risk associations. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2012; 47:1026–1033.

28. Wang XS, Tan TN, Shek LP, Chng SY, Hia CP, Ong NB, Ma S, Lee BW, Goh DY. The prevalence of asthma and allergies in Singapore; data from two ISAAC surveys seven years apart. Arch Dis Child. 2004; 89:423–426.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download