2. Bousquet J, Khaltaev N, Cruz AA, Denburg J, Fokkens WJ, Togias A, Zuberbier T, Baena-Cagnani CE, Canonica GW, van Weel C, Agache I, Aït-Khaled N, Bachert C, Blaiss MS, Bonini S, Boulet LP, Bousquet PJ, Camargos P, Carlsen KH, Chen Y, Custovic A, Dahl R, Demoly P, Douagui H, Durham SR, van Wijk RG, Kalayci O, Kaliner MA, Kim YY, Kowalski ML, Kuna P, Le LT, Lemiere C, Li J, Lockey RF, Mavale-Manuel S, Meltzer EO, Mohammad Y, Mullol J, Naclerio R, O'Hehir RE, Ohta K, Ouedraogo S, Palkonen S, Papadopoulos N, Passalacqua G, Pawankar R, Popov TA, Rabe KF, Rosado-Pinto J, Scadding GK, Simons FE, Toskala E, Valovirta E, van Cauwenberge P, Wang DY, Wickman M, Yawn BP, Yorgancioglu A, Yusuf OM, Zar H, Annesi-Maesano I, Bateman ED, Ben Kheder A, Boakye DA, Bouchard J, Burney P, Busse WW, Chan-Yeung M, Chavannes NH, Chuchalin A, Dolen WK, Emuzyte R, Grouse L, Humbert M, Jackson C, Johnston SL, Keith PK, Kemp JP, Klossek JM, Larenas-Linnemann D, Lipworth B, Malo JL, Marshall GD, Naspitz C, Nekam K, Niggemann B, Nizankowska-Mogilnicka E, Okamoto Y, Orru MP, Potter P, Price D, Stoloff SW, Vandenplas O, Viegi G, Williams D. Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) 2008 update (in collaboration with the World Health Organization, GA(2)LEN and AllerGen). Allergy. 2008; 63(Suppl 86):8–160. PMID:

18331513.

5. Bousquet J, Schünemann HJ, Samolinski B, Demoly P, Baena-Cagnani CE, Bachert C, Bonini S, Boulet LP, Bousquet PJ, Brozek JL, Canonica GW, Casale TB, Cruz AA, Fokkens WJ, Fonseca JA, van Wijk RG, Grouse L, Haahtela T, Khaltaev N, Kuna P, Lockey RF, Lodrup Carlsen KC, Mullol J, Naclerio R, O'Hehir RE, Ohta K, Palkonen S, Papadopoulos NG, Passalacqua G, Pawankar R, Price D, Ryan D, Simons FE, Togias A, Williams D, Yorgancioglu A, Yusuf OM, Aberer W, Adachi M, Agache I, Aït-Khaled N, Akdis CA, Andrianarisoa A, Annesi-Maesano I, Ansotegui IJ, Baiardini I, Bateman ED, Bedbrook A, Beghé B, Beji M, Bel EH, Ben Kheder A, Bennoor KS, Bergmann KC, Berrissoul F, Bieber T, Bindslev Jensen C, Blaiss MS, Boner AL, Bouchard J, Braido F, Brightling CE, Bush A, Caballero F, Calderon MA, Calvo MA, Camargos PA, Caraballo LR, Carlsen KH, Carr W, Cepeda AM, Cesario A, Chavannes NH, Chen YZ, Chiriac AM, Chivato Pérez T, Chkhartishvili E, Ciprandi G, Costa DJ, Cox L, Custovic A, Dahl R, Darsow U, De Blay F, Deleanu D, Denburg JA, Devillier P, Didi T, Dokic D, Dolen WK, Douagui H, Dubakiene R, Durham SR, Dykewicz MS, El-Gamal Y, El-Meziane A, Emuzyte R, Fiocchi A, Fletcher M, Fukuda T, Gamkrelidze A, Gereda JE, González Diaz S, Gotua M, Guzmán MA, Hellings PW, Hellquist-Dahl B, Horak F, Hourihane JO, Howarth P, Humbert M, Ivancevich JC, Jackson C, Just J, Kalayci O, Kaliner MA, Kalyoncu AF, Keil T, Keith PK, Khayat G, Kim YY, Koffi N'goran B, Koppelman GH, Kowalski ML, Kull I, Kvedariene V, Larenas-Linnemann D, Le LT, Lemière C, Li J, Lieberman P, Lipworth B, Mahboub B, Makela MJ, Martin F, Marshall GD, Martinez FD, Masjedi MR, Maurer M, Mavale-Manuel S, Mazon A, Melen E, Meltzer EO, Mendez NH, Merk H, Mihaltan F, Mohammad Y, Morais-Almeida M, Muraro A, Nafti S, Namazova-Baranova L, Nekam K, Neou A, Niggemann B, Nizankowska-Mogilnicka E, Nyembue TD, Okamoto Y, Okubo K, Orru MP, Ouedraogo S, Ozdemir C, Panzner P, Pali-Schöll I, Park HS, Pigearias B, Pohl W, Popov TA, Postma DS, Potter P, Rabe KF, Ratomaharo J, Reitamo S, Ring J, Roberts R, Rogala B, Romano A, Roman Rodriguez M, Rosado-Pinto J, Rosenwasser L, Rottem M, Sanchez-Borges M, Scadding GK, Schmid-Grendelmeier P, Sheikh A, Sisul JC, Solé D, Sooronbaev T, Spicak V, Spranger O, Stein RT, Stoloff SW, Sunyer J, Szczeklik A, Todo-Bom A, Toskala E, Tremblay Y, Valenta R, Valero AL, Valeyre D, Valiulis A, Valovirta E, Van Cauwenberge P, Vandenplas O, van Weel C, Vichyanond P, Viegi G, Wang DY, Wickman M, Wöhrl S, Wright J, Yawn BP, Yiallouros PK, Zar HJ, Zernotti ME, Zhong N, Zidarn M, Zuberbier T, Burney PG, Johnston SL, Warner JO. Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA): achievements in 10 years and future needs. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012; 130:1049–1062. PMID:

23040884.

6. King HC, Mabry RL, Mabry CS, Gordon BR, Marple BF. Allergy in ENT practice: the basic guide. 2nd ed. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers;2004.

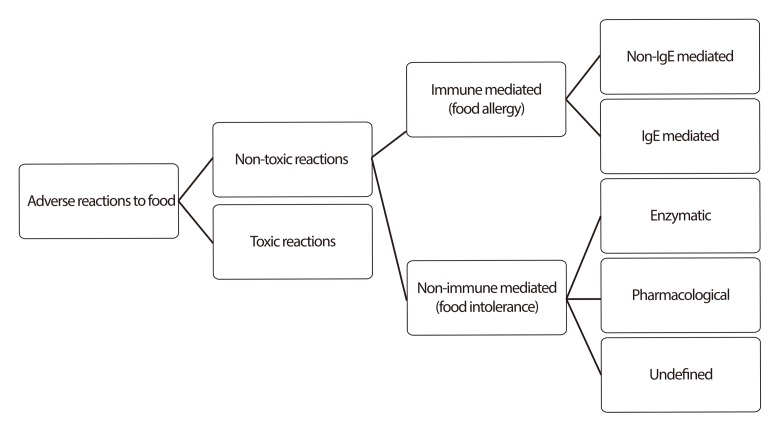

8. Dean T. Food intolerance and the food industry. 1st ed. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing Limited;2000.

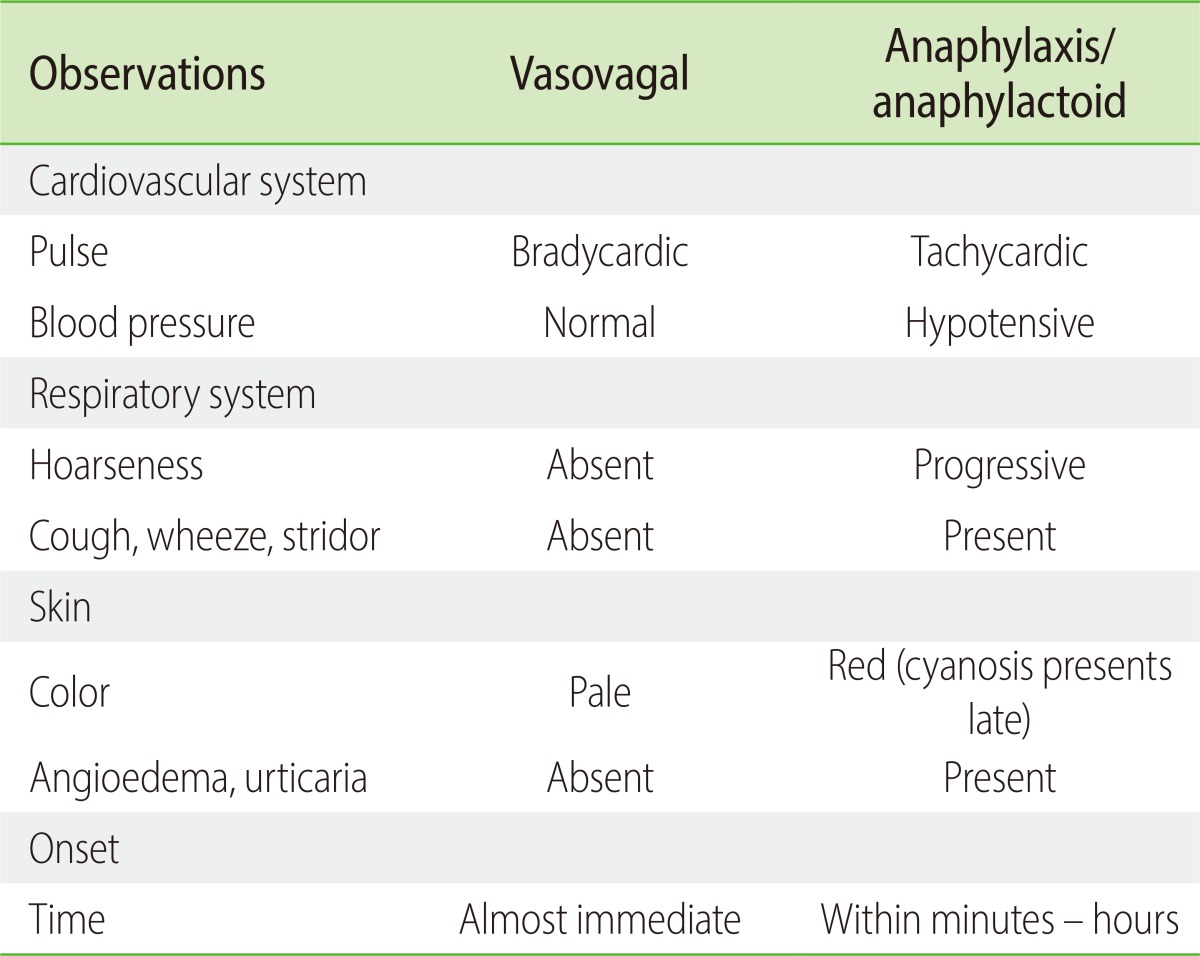

10. Australian Government, Department of Health and Ageing. Clinical Features that may assist differentiation between a vasovagal episode and anaphylaxis. The Australian Immunization Handbook. Canberra: Australian Government, Department of Health and Ageing;2013. p. 88.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download