Abstract

Background

Upper respiratory diseases have been linked with lower respiratory diseases. However, the long-term effect of sinusitis on the clinical outcomes of asthma has not been fully evaluated.

Objective

The aim of this study was to investigate the impact of sinusitis on the disease progression of asthma.

Methods

Seventy-five asthmatic patients confirmed with the methacholine bronchial provocation test or bronchodilator response were included. The study patients underwent paranasal sinus x-ray upon their asthma evaluation and they visited the hospital at least 3 years or longer. We retrospectively reviewed their medical records and compared data according to the presence of comorbid sinusitis.

Results

Among the 75 asthmatic subjects, 38 subjects (50.7%) had radiologic evidence of sinusitis. Asthmatics with sinusitis had significantly lower forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1; 79.2% vs. 88.2%) and PC20 values (5.2 mg/mL vs. 8.9 mg/mL) compared to asthmatics without sinusitis at the time of diagnosis. This difference in FEV1 disappeared (82.6% vs. 87.2%) in the 3-year follow-up, although FEV1 was more variable (31.7% vs. 23.5%) and worst FEV1 was also significantly lower in patients with sinusitis compared to those without (70.9% vs. 79.0%). There were no significant differences in the number of hospital visits, acute exacerbations, and scores for the asthma control test.

Conclusion

Although sinusitis was associated with lower baseline lung function and higher hyperreactivity, sinusitis was not related with significant deterioration in lung function over 3 years of follow-up. Asthmatics with sinusitis showed more variability in lung function during the follow-up period. Healthcare utilization was not different except antibiotics use.

Since many studies have investigated the association of rhinosinusitis and asthma, it has become a widely accepted concept that these two diseases are not separate and distinct disease entities but interrelated diseases of one airway. The upper and lower airways are connected to each other anatomically and both are composed of pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium and have innate and acquired immune defense mechanisms [1, 2]. If patients have either rhinosinusitis or asthma, they would be accompanied by the other disease with significantly higher frequency [3]. Asthma prevalence in the general population is 5-8% but it reaches up to 20% among chronic sinusitis patients [3]. Closely related with this, 75% of patients with asthma have chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) symptoms [4], and 84% of patients with severe asthma have sinusitis in the computed tomography (CT) findings [5].

The mechanisms that explain the association between rhinosinusitis and asthma include nasopharyngeal-bronchial reflex, postnasal drip of inflammatory material, and common pathogenic mechanisms such as systemic inflammatory diseases [3]. Despite these concepts, there have been only a few studies that verified whether sinusitis could affect the long-term progress of asthma and most studies evaluated mainly the effects of surgical intervention or were done with children [6, 7]. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the long-term effect of sinusitis on the course of adult asthma.

We enrolled asthma patients who were diagnosed with the methacholine bronchial challenge test or bronchodilator response and evaluated with paranasal sinus (PNS) x-ray as a work up for their asthma from January 2005 to March 2007. Current and ex-smokers, and patients lost to follow-up within 3 years were excluded. Patients were divided by PNS x-ray results as asthma patients with sinusitis and without sinusitis during the 3 years of follow-up.

We reviewed the medical records of the study subjects retrospectively. Clinical characteristics (age, sex, outpatient visits over 3 years, admission to the Emergency Department or wards due to asthma exacerbation, and on the asthma control test (ACT) score [8], laboratory test (total IgE, peripheral blood leukocyte count, and peripheral blood eosinophil count), airway hyperresponsiveness (provocative concentration of methacholine causing a 20% fall in forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1], PC20), baseline and follow-up spirometric values, and history of medication use were compared based on the presence or absence of sinusitis. Prescription of systemic steroids and antibiotics were also reviewed.

Pulmonary function test was done with a spirometry system (SensorMedics 2130, SensorMedics, Yorba Linda, CA, USA). The methacholine challenge test was performed as the Chai method with some modifications [9]. After the basal lung function was measured, the methacholine challenge test was done with concentrations of 0.25, 0.625, 1, 4, 16, and 25 mg/mL. PC20 was considered positive when it was 25 mg/mL or less. FEV1 variability during 3 years was calculated as follow: FEV1 variability = (best FEV1 (mL) -worst FEV1 (mL))/[(best FEV1 (mL) + worst FEV1 (mL))/2].

If any one of the findings that included mucosal thickening, opacity, and air-fluid level was observed in the PNS x-ray, the subject was considered as having comorbid sinusitis [10].

Skin prick test was performed with 55 kinds of common inhaled allergens (Allergopharma GmbH & Co. KG, Reinbek, Germany), and histamine (1 mg/mL) and saline were used as the positive and negative control, respectively. The results were read after 15 minutes. The wheal size by allergen (A) was compared to the wheal size by histamine (H), and an A/H ratio higher than 1 was considered as positive. The atopy index was calculated as the number of inhaled allergens which showed a positive result on the skin prick test. The atopy score was defined as the mean diameter of the wheals showing positive reactions on the skin prick test [11].

IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 19.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA) was used to analyze the data. Spirometric values, PC20, total IgE, eosinophil count, atopy index, atopy score, frequency of hospital visits, and frequency of exacerbations were compared using Student t-test, and adjusted for age and sex by multiple linear regression. The association of sinusitis and medication use was verified by the chi-square test. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Measurements were expressed as the means ± standard deviation.

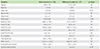

There were 75 patients enrolled. The mean age of the subjects was 57.0 ± 14.7 years and 9 (12%) were male. The baseline subject demographics were compared according to the presence or absence of sinusitis (Table 1). There were no significant differences in age, gender, atopic index, or atopic score between the two groups.

The FEV1 (%, predicted value) at study entry was significantly lower in asthma patients with sinusitis than in those without sinusitis, 79.2% vs. 88.2% (p = 0.031). This difference was sustained after adjusting for age and gender. The FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio trended lower in asthmatic patients with sinusitis, but did not reach significance, 72.6% vs. 76.1%, (p = 0.076). The PC20 was significantly lower in asthma patients with sinusitis, 5.2 mg/mL vs. 8.9 mg/mL, (p = 0.017). The FVC (%, predicted value) was not significantly different between the two groups, 90.0% vs. 96.9% (p = 0.117). Total IgE levels, 308.3 IU/mL vs. 154.1 IU/mL (p = 0.191), leukocyte counts, 7,226.7/mm3 vs. 6,892.8/mm3 (p = 0.500), and peripheral blood eosinophil counts, 395.3/mm3 vs. 296.1/mm3 (p = 0.168) also did not show statistically significant differences between the two groups. The sputum eosinophil percentages were higher in asthmatic patients with sinusitis than in those without sinusitis, 13.1% vs. 6.6% (p = 0.026).

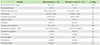

The best recorded FEV1 during the three year follow-up did not differ between the two groups, 96.0% vs. 99.0% (p = 0.452). On the contrary, a worst FEV1 was significantly lower (70.9% vs. 79.0%, p = 0.046) and FEV1 variability was greater (31.7% vs. 23.5%, p = 0.040) in patients with sinusitis compared to those without sinusitis (Fig. 1). These differences were sustained after adjusting for age and gender. The number of hospital visits and the frequency of acute asthma exacerbations were not different between the two groups (Table 2).

There were no significant differences in the proportion of patients who received systemic steroids or antibiotics, or in the total dose of systemic steroids used. However, patients with sinusitis were prescribed antibiotics for significantly longer periods compared to those without sinusitis, 39.5 days vs. 18.0 days (p = 0.013). There was no significant difference in the frequency of use of antiasthmatic drugs such as inhaled steroids, inhaled long-acting β-agonists, leukotriene modifiers, theophylline, and anticholinergics or in the frequency of use of rhinitis medications such as antihistamines and intranasal steroids (Table 2).

After 3 years of follow-up, the FEV1 and FEV1/FVC significantly improved in patients with sinusitis (79.2% vs. 82.6%, p = 0.046 and 72.6% vs. 76.0%, p = 0.001, respectively). The FEV1 and FEV1/FVC did not significantly change in patients without sinusitis (88.2% vs. 87.2%, p = 0.503 and 76.1% vs. 77.7%, p = 0.050, respectively). As a result, the initial difference in FEV1 between the two groups disappeared after 3 years of follow-up (82.6% vs. 87.2%, p = 0.262) (Fig. 1). Peripheral blood leukocyte and eosinophil counts at 3 years after diagnosis were not different between the two groups (Table 2). The ACT score after 3 years did not differ depending on the presence of sinusitis (Table 2).

Although there have been many studies and reports about the relationship between upper airway and lower airway diseases [5, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19], sinusitis has not been intensively studied in terms of its impact on asthma compared to allergic rhinitis [20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25]. Even until currently, there have been only a few epidemiologic studies on CRS and asthma, and that was investigated in 2012 [12]. In that study, asthma and CRS was associated strongly (odds ratio, 3.47; 95% confidence interval, 3.20-3.76), and CRS without nasal allergies was associated with late-onset asthma [12].

Chronic sinusitis is one of the common upper respiratory diseases and known to affect airway hyperresponsiveness of the lower airways [26]. Ponikau et al. [26] had showed that 91% of CRS patients without asthma revealed airway hyperresponsiveness by methacholine challenge test and asthma patients with sinusitis showed more severe airway hyperresponsiveness than those without sinusitis in the current study.

In a previously reported study, eosinophil counts in the blood and sputum of asthma patients were correlated with the CT score of their sinusitis, which suggested that asthma and sinusitis is a combined single inflammatory disease [27]. In the current study, sputum eosinophil counts of asthma patients with sinusitis were two times higher than patients without sinusitis and blood eosinophil counts and total IgE also showed a tendency to be higher in the group with sinusitis though without statistical significance.

To date, studies over the impact of sinusitis on asthma have been mainly about the surgical intervention of sinusitis or done with children patients [28, 29, 30, 31]. In one study, 78% of pediatric patients who suffered from chronic respiratory symptoms more than 3 months and used bronchodilator every day were able to stop the bronchodilator after 2-5 weeks of antibiotic treatment for sinusitis [6]. This research revealed that sinusitis could be an aggravating factor of asthma and that treatment of sinusitis could improve the clinical course of asthma. Friedman et al. [7] also showed that asthma symptoms and lung function improved after antibiotic treatment of sinusitis over 2-4 weeks in asthmatic patients with bacterial sinusitis. In addition, a few studies observed short term improvement in asthma after medical treatment of sinusitis in children [12, 13]; however, research observed long-term effects in adult patients have been limited.

In this study, we analyzed the effect of sinusitis on the long-term clinical outcome of asthma in adult patients. We observed that baseline lung function was lower and airway hyperresponsiveness and eosinophilic airway inflammation was more severe in the asthma patients with sinusitis than in those without sinusitis. These results suggest that sinusitis contributed to the aggravation of lower airway inflammation. However, after 3 years active treatment for asthma and sinusitis, the initial difference in lung function between the two groups disappeared by improvement in lung function in the patients with sinusitis.

Previously, ten Brinke et al. [16] revealed that chronic severe sinus disease is a risk factor of frequent asthma exacerbation in difficult-to-treat asthma patients. The study revealed that severe chronic sinusitis is an independent risk factor of frequent asthma exacerbations. In our study, there was no difference in the rate of patients who experienced acute exacerbations and in the frequency of exacerbations between the two groups. There were no differences in the use of systemic steroids, asthma medications, and rhinitis medications according to comorbid sinusitis. However, the findings that patients with sinusitis showed significantly larger fluctuations of FEV1 and lower worst FEV1 suggest comorbid sinusitis make the patients more vulnerable to asthma exacerbations. Hence, asthma patients with sinusitis can have favorable outcomes in respect to long term lung function; however, they still should be educated about their susceptibility to asthma exacerbations and pay attention to sinus management.

There are several limitations in this study. First of all, we only defined sinusitis as radiologic findings of simple PNS x-ray; therefore, we could not differentiate between acute and chronic sinusitis. In addition, a recent guideline suggested that the definition of CRS is based on characteristic symptoms (≥2 of the followings nasal congestion, facial pain/pressure, anterior or posterior nasal drainage, and reduced or absent sense of smell) that last over 12 weeks and over the imaging studies [32]. When considering the research design of our study which was a retrospective study, we could not collect information about the patients' symptoms in detail. Because of our retrospective study design, we could not collect all information about reasons of antibiotics prescription, asthma exacerbation and variable lung function. We could consider that antibiotics might be prescribed to control other diseases, such as upper respiratory infections (URI). Viral infection, air pollutants, aspirin medication could also affect asthma exacerbation and variable lung function and these factors could not be excluded. However, asthma patients with sinusitis could be more vulnerable to viral infection (URI) or air pollutants and more accompanied by nasal polyp and aspirin hypersensitivity. Therefore, these factors could be one of the characteristics of asthma patients with sinusitis. In the future study, we have to gather information about exact reasons for antibiotics use and asthma exacerbation. Second, we did not evaluate additional examinations routinely other than the simple x-rays, for example, rhinoscopy or PNS CT or magnetic resonance imaging for identifying polyps in the nasal cavity. The presence of polyps could be an important factor because the future direction of treatment may be different [32]. Third, aspirin hypersensitivity was not checked, which could be associated with CRS with nasal polyp and asthma and might be candidates for treatment with aspirin desensitization [32]. Finally, although this was the first study that observed the long-term follow-up of adult asthma patients according to the presence or absence of sinusitis, a three-year study might be a relatively short period to conclude the long-term effects of sinusitis on asthma and it is difficult to clarify the causal relationship between sinusitis and lung function variability. Therefore, a study that examines a longer period with a prospective design will be needed.

In conclusion, comorbid sinusitis was related with lower lung function, higher airway hyperreactivity, and more variable lung function despite anti-asthmatic treatment; however, after 3 years of continuous treatment, they showed good treatment response; consequently, the lung functions between the two groups became similar. Sinusitis may have a negative impact on asthma initially; however, it can be overcome by steady treatment of asthma and sinusitis.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Serial change in spirometric values after 3 years according to comorbid sinusitis in asthmatics patients. (A) Forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) predictive value was improved only in asthma patients with sinusitis; therefore, an initial gap between the sinusitis group and without sinusitis group disappeared after 3 years. (B) Best FEV1 predictive value during 3 years showed no difference between sinusitis group and without sinusitis group. (C) Asthma patients with sinusitis showed a lower FEV1 predictive value than those without sinusitis. (D) FEV1 variability was higher in asthma patients in the sinusitis group than in those in the sinusitis group. *p < 0.05, statistically significant. |

Table 1

Comparison of demographics and clinical characteristics at the time of initial diagnosis of asthma according to the comorbid sinusitis

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation or number (%).

NS, not significant; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; PC20, provocative concentration causing a 20% drop in FEV1; WBC, white blood cell.

*Nasal polyp was evaluated by paranasal sinus computed tomography or rhinoscopy. †Multiple linear regression analysis with adjustment for age, sex.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from the Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project, Ministry for Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (A102065).

References

1. Hellings PW, Hens G. Rhinosinusitis and the lower airways. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2009; 29:733–740.

3. Jani AL, Hamilos DL. Current thinking on the relationship between rhinosinusitis and asthma. J Asthma. 2005; 42:1–7.

4. Bresciani M, Paradis L, Des Roches A, Vernhet H, Vachier I, Godard P, Bousquet J, Chanez P. Rhinosinusitis in severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001; 107:73–80.

5. ten Brinke A, Grootendorst DC, Schmidt JT, De Bruïne FT, van Buchem MA, Sterk PJ, Rabe KF, Bel EH. Chronic sinusitis in severe asthma is related to sputum eosinophilia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002; 109:621–626.

6. Rachelefsky GS, Katz RM, Siegel SC. Chronic sinus disease with associated reactive airway disease in children. Pediatrics. 1984; 73:526–529.

7. Friedman R, Ackerman M, Wald E, Casselbrant M, Friday G, Fireman P. Asthma and bacterial sinusitis in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1984; 74:185–189.

8. Nathan RA, Sorkness CA, Kosinski M, Schatz M, Li JT, Marcus P, Murray JJ, Pendergraft TB. Development of the asthma control test: a survey for assessing asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004; 113:59–65.

9. Chai H. Antigen and methacholine challenge in children with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1979; 64(6 pt 2):575–579.

10. Stelmach R, Junior SA, Figueiredo CM, Uezumi K, Genu AM, Carvalho-Pinto RM, Cukier A. Chronic rhinosinusitis in allergic asthmatic patients: radiography versus low-dose computed tomography evaluation. J Asthma. 2010; 47:599–603.

11. Laprise C, Boulet LP. Asymptomatic airway hyperresponsiveness: a three-year follow-up. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997; 156(2 Pt 1):403–409.

12. Jarvis D, Newson R, Lotvall J, Hastan D, Tomassen P, Keil T, Gjomarkaj M, Forsberg B, Gunnbjornsdottir M, Minov J, Brozek G, Dahlen SE, Toskala E, Kowalski ML, Olze H, Howarth P, Kramer U, Baelum J, Loureiro C, Kasper L, Bousquet PJ, Bousquet J, Bachert C, Fokkens W, Burney P. Asthma in adults and its association with chronic rhinosinusitis: the GA2LEN survey in Europe. Allergy. 2012; 67:91–98.

13. Dixon AE, Kaminsky DA, Holbrook JT, Wise RA, Shade DM, Irvin CG. Allergic rhinitis and sinusitis in asthma: differential effects on symptoms and pulmonary function. Chest. 2006; 130:429–435.

14. Litvack JR, Fong K, Mace J, James KE, Smith TL. Predictors of olfactory dysfunction in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2008; 118:2225–2230.

15. Bachert C, Zhang N, Holtappels G, De Lobel L, van Cauwenberge P, Liu S, Lin P, Bousquet J, Van Steen K. Presence of IL-5 protein and IgE antibodies to staphylococcal enterotoxins in nasal polyps is associated with comorbid asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010; 126:962–968. 968.e1–968.e6.

16. ten Brinke A, Sterk PJ, Masclee AA, Spinhoven P, Schmidt JT, Zwinderman AH, Rabe KF, Bel EH. Risk factors of frequent exacerbations in difficult-to-treat asthma. Eur Respir J. 2005; 26:812–818.

17. Lotvall J, Ekerljung L, Lundback B. Multi-symptom asthma is closely related to nasal blockage, rhinorrhea and symptoms of chronic rhinosinusitis-evidence from the West Sweden Asthma Study. Respir Res. 2010; 11:163.

19. Tomassen P, Van Zele T, Zhang N, Perez-Novo C, Van Bruaene N, Gevaert P, Bachert C. Pathophysiology of chronic rhinosinusitis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2011; 8:115–120.

20. Fuhlbrigge AL, Adams RJ. The effect of treatment of allergic rhinitis on asthma morbidity, including emergency department visits. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003; 3:29–32.

21. Stelmach R, do Patrocinio T Nunes M, Ribeiro M, Cukier A. Effect of treating allergic rhinitis with corticosteroids in patients with mild-to-moderate persistent asthma. Chest. 2005; 128:3140–3147.

22. Choi SH, Kim do K, Yoo Y, Yu J, Koh YY. Comparison of deltaFVC between patients with allergic rhinitis with airway hypersensitivity and patients with mild asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007; 98:128–133.

23. Ciprandi G, Cirillo I, Pistorio A. Impact of allergic rhinitis on asthma: effects on spirometric parameters. Allergy. 2008; 63:255–260.

24. Guerra S, Sherrill DL, Martinez FD, Barbee RA. Rhinitis as an independent risk factor for adult-onset asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002; 109:419–425.

25. Sherrill DL, Guerra S, Minervini MC, Wright AL, Martinez FD. The relation of rhinitis to recurrent cough and wheezing: a longitudinal study. Respir Med. 2005; 99:1377–1385.

26. Ponikau JU, Sherris DA, Kephart GM, Kern EB, Gaffey TA, Tarara JE, Kita H. Features of airway remodeling and eosinophilic inflammation in chronic rhinosinusitis: is the histopathology similar to asthma? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003; 112:877–882.

27. Jaaskelainen IP, Ahveninen J, Andermann ML, Belliveau JW, Raij T, Sams M. Short-term plasticity as a neural mechanism supporting memory and attentional functions. Brain Res. 2011; 1422:66–81.

28. Senior BA, Kennedy DW, Tanabodee J, Kroger H, Hassab M, Lanza DC. Long-term impact of functional endoscopic sinus surgery on asthma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999; 121:66–68.

29. Manning SC, Wasserman RL, Silver R, Phillips DL. Results of endoscopic sinus surgery in pediatric patients with chronic sinusitis and asthma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994; 120:1142–1145.

30. Palmer JN, Conley DB, Dong RG, Ditto AM, Yarnold PR, Kern RC. Efficacy of endoscopic sinus surgery in the management of patients with asthma and chronic sinusitis. Am J Rhinol. 2001; 15:49–53.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download