Abstract

Background

Chronic urticaria is termed as idiopathic if there is an absence of any identifiable causes of mast cell and basophil degranulation. Various cytokines have been found to be involved in inflammatory processes associated with chronic idiopathic urticaria, including interleukin (IL) 18 and IL-6.

Objective

To evaluate any possible correlation of IL-18 and IL-6 cytokines with the clinical disease severity in chronic idiopathic urticaria (CIU).

Methods

IL-18 and IL-6 levels of CIU patients (n = 62) and healthy controls (n = 27) were assessed by commercially available enzyme linked immunosorbent assay kits following the manufacturer's protocols.

Results

Serum IL-18 concentration (mean ± standard deviation [SD], 62.95 ± 36.09 pg/mL) in CIU patients and in healthy controls (54.35 ± 18.45 pg/mL) showed no statistical significance (p > 0.05). No statistically significant difference (p > 0.05) was observed between autologous serum skin test (ASST) positive and ASST negative patients with regard to the serum IL-18 levels either. Similarly, serum IL-6 concentration (0.82 ± 4.6 pg/mL) in CIU patients and in healthy controls (0.12 ± 1.7 pg/mL), showed no statistical significance (p > 0.05). Also, comparison between positive and ASST negative patients with regard to the serum IL-6 levels was statistically nonsignificant (p > 0.05). However, statistical significance was found both in IL-18 and IL-6 concentrations in certain grades with regard to the clinical disease severity of urticaria.

Urticaria involves the superficial portion of the dermis, presenting as well-circumscribed wheals with erythematous raised serpeginous borders with blanched centers that may coalesce to become giant wheals whose recurrent episodes persisting beyond 6 weeks duration are termed chronic [1]. The basic mechanism for the urticaria is degranulation of tissue mast cells and basophils (either immunological, nonimmunological or idiopathic) [2]. There is evidence for histamine releasing activity in chronic urticaria (CU) due to autoantibodies against to either IgE or high affinity IgE receptor (FcεRIα) [3]. The autologous serum skin test (ASST) is an in vivo screening test for histamine releasing autoantibodies and other vasoactive factors, and allows distinction between chronic autoimmune and chronic idiopathic urticaria (CIU) [4, 5].

Interleukin (IL) 18 is a pleiotropic cytokine produced by monocytes/macrophages, dendritic cells, keratinocytes, Langerhans' cells and B cells, which can activate T cells and induce either T helper Th1 or Th2 responses, depending on the cytokine environment [6]. It has been suggested that IL-18 may play an important role either in autoimmune disorders, characterized by a predominant Th1 response, or in allergic diseases, characterized by a Th2 response [7]. IL-6 is believed to be the central regulator of the immunological and inflammatory processes and in humans the cytokine is elevated in many inflammatory diseases [8, 9]. This inflammation-associated cytokine is produced by a variety of cell types, including mast cells [10]. The increased secretion of IL-6 occurs during various immune-inflammatory processes, including hypersensitivity reactions and autoimmune diseases [11, 12].

Few studies have shown the involvement of IL-18 and IL-6 in inflammatory processes associated with CIU. Thus in the present study, we measured serum IL-18 and IL-6 levels in patients with CIU so as to evaluate any possible association of these cytokines with the clinical disease severity.

Sixty-two patients (42 females and 20 males) with CIU were included in the study of IL-18 and IL-6. Blood samples were collected during the period from November 2010 to March 2013 by the Allergy & Immunology outpatient department clinic of the Department of Immunology & Molecular Medicine, SKIMS Srinagar Kashmir. The age of the subjects ranged from 7-65 years. The diagnosis was dependent on the recurrence of wheals with or without angioedema for more than 6 weeks. In all the patients, the known causes of chronic or recurrent urticaria were ruled out by careful history taking and by the proper investigations. Patients with physical urticaria or other chronic inflammatory diseases including atopic dermatitis were excluded from the study. Twenty-seven gender and age matched healthy subjects respectively for IL-18 and IL-6 were used as a control group. Informed consents were obtained from patients and control subjects.

Patients discontinued antihistamines 5 days prior to the date of testing. Disease activity was estimated according to the number of wheals present at the time when the serum samples for the patients were collected as per the following criteria: mild/grade I, 1-10 small wheals (<3 cm in diameter); moderate/grade II, 10-50 small wheals or 1-10 large wheals; severe/grade III, ≥50 small wheals or >10 large wheals; and very severe/grade IV, body fully covered with wheals. In addition, all the patients underwent the ASST, the test was performed by an intradermal injection of 0.05 mL of fresh autologous serum and read after 30 minutes. We used a normal saline solution (0.9% NaCl sol) injected intradermally as a negative control and histamine solution 1 mg/mL for the skin prick test as a positive control. Wheals 1.5 mm greater than that produced by the normal saline were considered positive.

Blood samples (2 mL from each patient) and from healthy controls were collected from time to time.The blood was allowed to clot at room temperature for exactly 60 ± 10 minutes. Then, the serum isolation was carried out by the centrifugation method at 3,000 rpm for 10 minutes. The serum was transferred to 1.5-mL labeled tubes, aliquoted and stored at -70℃.

Serum IL-18 concentration was measured by using a sandwich enzyme immunoassay with a sensitivity of 12.5 pg/mL using a commercially available human IL-18 enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (MBL-Medical and Biological Laboratories, Nagoya, Japan) as per the manufacturer's instructions. This assay uses two monoclonal antibodies against two different epitopes of human IL-18. Samples to be measured or standards are incubated in the microwells coated with antihuman IL-18 monoclonal antibody. After washing, the peroxidase conjugated antihuman IL-18 monoclonal antibody is added into the microwells and incubated. After another washing, the substrate reagent is mixed with the chromogen and allowed to incubate for an additional period of time. An acid solution is added to each microwell to terminate the enzyme reaction and to stabilize the color development. The optical density (OD) of each microwell is measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader. The concentration of human IL-18 is calibrated from a dose response curve based on the reference standards.

Serum IL-6 concentration was measured by using ELISA with a sensitivity of 2 pg/mL using a commercially available human IL-6 ELISA kit (Gen-Probe, Diaclone France) as per the manufacturer's instructions. Binding of IL-6 samples and known standards to the capture antibodies and subsequent binding of the biotinylated anti-IL-6 secondary antibody to the analyte is completed during the same incubation period. Any excess unbound analyte & secondary antibody is removed. The HRP-conjugate is removed by careful washing. A chromogen substrate is added to the wells resulting in the progressive development of a blue colored complex with the conjugate. The color development is then stopped by the addition of acid turning the resultant final product yellow. The intensity of the produced colored complex is directly proportional to the concentration of IL-6 present in the samples & standards. The absorbance of the colored complex is then measured & the generated OD values for each standard are plotted against expected concentration forming a standard curve.

Discrete variables are reported as frequency, proportions and continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Normally distributed interval data are reported as means (SD) and evaluated by unpaired t-test. Categorical data was compared using chi-square test. GraphPad Prism ver. 6.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) was used for all statistical analysis and all tests are two sided and p-value considered <0.05 as significant.

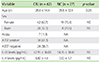

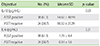

The study comprised of 62 patients with CIU with age ranged from 7-65 years; the mean age was 28 years with females outnumbering males. 61.3% patients (n = 38) were ASST positive, while as, 38.7% patients (n = 24) were ASST negative. Mostly females were ASST positive (81.6% out of 38). The serum IL-18 levels in pg/mL were (62.95 ± 36.09 pg/mL) in CIU patients and in healthy control it was (54.35 ± 18.45 pg/mL). There was no statistically significant difference (p = 0.24) with regard to serum IL-18 levels between patients and healthy controls as shown in Table 1. When the serum IL-18 levels in pg/mL were compared in CIU patients according to the results of the ASST, again there was no statistically significant difference (p = 0.65). The IL-18 levels in ASST positive patients were (64.60 ± 40.94 pg/mL) and in ASST negative patients, the levels were (60.32 ± 27.29 pg/mL) as shown in Table 2.

When the patients with CIU were grouped according to the severity of the disease, the highest serum IL-18 levels were detected in patients with severe disease with a statistical significance found in grade III (n = 8) and grade IV (n = 2) (p < 0.05) among the ASST positive patients when compared with grade I (n = 16) (Fig. 1). However, in case of ASST negative patients statistical significance was found in grade III (n = 3) only when compared to grade I (n = 16) as shown in Fig. 2.

The Serum IL-6 levels in pg/mL was (0.82 ± 4.6 pg/mL) in CIU patients and in healthy control it was (0.12 ± 1.7 pg/mL). There was no statistically significant difference (p = 0.44) with regard to serum IL-6 levels between patients and healthy controls as shown in Table 1. When the serum IL-6 levels in pg/mL were compared in CIU patients according to the results of the ASST, again there was no statistically significant difference (p = 0.31). The IL-6 levels in ASST positive patients were (1.29 ± 4.4 pg/mL) and in ASST negative patients, the levels were (0.34 ± 1.6 pg/mL) as shown in Table 2.

When the patients with CIU were grouped according to the severity of the disease, the highest serum IL-6 levels were detected in patients with severe disease with a statistical significance found in grade II (n = 12), grade III (n = 8), and grade IV (n = 2) (p < 0.05) among the ASST positive patients when compared with grade I (n = 16) (Fig. 3). In case of ASST negative patients, statistical significance was also found in grades II (n = 5) and III (n = 3) (p < 0.05) when compared with grade I (n = 16) as shown in Fig. 4.

The main purpose of this study was to evaluate the status and/or correlation of serum IL-18 levels in the patients with CIU. In our study we found that there was no statistically significant difference (p = 0.14) with regard to serum IL-18 levels between CIU patients and healthy controls. Tedeschi et al. [13] did not find any difference in IL-18 serum levels between CSU patients and healthy controls but, interestingly, in the ASST-positive group the IL-18 level correlated with the clinical activity of urticaria assessed by the clinical severity score. In this study we also found that the comparison between the serum IL-18 levels in the ASST positive patients versus the ASST negative patients proved statistically nonsignificant (p = 0.65). The results are in agreement with the study done by Ibrahim and Khalifa [14] which shows that the serum IL-18 levels did not differ between ASST positive and ASST negative groups. On the contrary, a correlation between IL-18 levels and ASST positive CU has been detected by Kurt et al. [15].

IL-18 binding protein (IL-18BP) is a circulating antagonist of the proinflammatory Th1 cytokine-IL-18, which effectively blocks IL-18 by forming a 1:1 high affinity complex thereby showing a very low dissociation rate. In this study we measured serum IL-18 concentration without distinction of free form by using a sandwich enzyme immunoassay. As we know sandwich ELISA is used for detecting IL-18BPa, while total IL-18 is measured by an electrochemiluminescence assay and free IL-18 is calculated by the mass action law. Herein we limited ourselves as per availability of resources and simply measured serum IL-18 levels without distinction of free form. Moreover, the mean IL-18 levels in CIU patients of this study were much lower (62.95 pg/mL) than previous studies (246.47 pg/mL) despite using the same ELISA kit, the probable cause would be impact of genetic variation in the study population. This ambiguity warrants further study and clarification.

When the patients with CIU were grouped according to the severity of the disease, the highest serum IL-18 levels were detected in patients with severe disease with a statistical significance found in grade III (n = 8) and grade IV (n = 2) (p < 0.05) among the ASST positive patients when compared with grade I (Fig. 1). This study is in agreement with the study conducted by Tedeschi et al. [13]. However, no significant correlation was found in case of ASST negative patients except in grade III (n = 3) when compared with grade I as shown in Fig. 2. Our data suggest that there is no statistical significance found as such between the serum IL-18 levels with the CIU patients, however, there is a statistical significance between IL-18 concentration and the clinical disease severity of urticaria. This kind of association with the urticarial activity scores indicates a potential role of IL-18 as a marker of the urticarial activity. This study is in agreement with the study done by Tedeschi et al. [13]. IL-18 is able to generate Th2 responses under certain conditions and promote allergic inflammation through the stimulation of IL-4, IL-13, and histamine release [7].

It is well known that IL-6 concentration is elevated in the peripheral circulation of patients with many inflammatory diseases. The source of IL-6 in CU has not been identified. Mast cells and other inflammatory cells types identified in skin biopsies of CU patients, including monocytes, basophils, eosinophils, activated T cells, and neutrophils release this cytokine [8, 9, 16, 17]. It has been suggested that IL-6 is involved in pathogenesis of severe acute urticaria, resistant to conventional antihistamine treatment [18]. In the present study, we found statistically higher serum concentration of IL-6 in CIU patients as compared with the healthy controls although, the comparison was statistically nonsignificant. This study is in agreement with the study done by Kasperska-Zajac et al. [10]. Elevated IL-6 plasma levels in CIU patients maybe a systemic manifestation of immune activation & inflammation in the skin, and that infection by several different viruses as well as bacterial products enhance IL-6 production [9].

The study showed that the comparison between serum IL-6 levels in the ASST positive and ASST negative patients is statistically nonsignificant (p = 0.31), however, there was a statistical significance between IL-6 concentration and the clinical disease severity of urticaria. This kind of association with the urticarial activity scores may indicate a potential role of IL-6 as a marker of the urticarial activity.

Thus, we conclude that there is no significant association as such between the IL-18 and IL-6 levels with CIU, however, both IL-18 and IL-6 may play an important role in immune activation in patients with CIU and may help in predicting the clinical disease severity. Hence, these cytokines may indicate a role as a biomarker to assess the disease severity in CIU.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Serum interleukin (IL) 18 levels in autologous serum skin test positive patients classified according to clinical severity score. SD, standard deviation. *p < 0.05, statistical significant.

Fig. 2

Serum interleukin (IL) 18 levels in autologous serum skin test negative patients classified according to clinical severity score. SD, standard deviation. *p < 0.05, statistical significant.

Fig. 3

Serum interleukin (IL) 6 levels in autologous serum skin test positive patients classified according to clinical/disease severity score. SD, standard deviation. *p < 0.05, statistical significant.

Fig. 4

Serum interleukin (IL) 6 levels in autologous serum skin test negative patients classified according to clinical/disease severity score. SD, standard deviation. *p < 0.05, statistical significant.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the entire staff of the Immunology & Molecular Medicine Department, SKIMS for their overwhelming support and help.

References

1. Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J. Chapter 311. Harrison's principles of internal medicine. 17th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical;2008. p. 2061–2074.

2. Ring J, Brockow K, Ollert M, Engst R. Antihistamines in urticaria. Clin Exp Allergy. 1999; 29:Suppl 1. 31–37.

4. Sabroe RA, Grattan CE, Francis DM, Barr RM, Kobza Black A, Greaves MW. The autologous serum skin test: a screening test for autoantibodies in chronic idiopathic urticaria. Br J Dermatol. 1999; 140:446–452.

5. Grattan CE. The urticaria spectrum: recognition of clinical patterns can help management. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004; 29:217–221.

6. Nakanishi K, Yoshimoto T, Tsutsui H, Okamura H. Interleukin-18 regulates both Th1 and Th2 responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001; 19:423–474.

7. Izakovicova Holla L. Interleukin-18 in asthma and other allergies. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003; 33:1023–1025.

8. Gabay C. Interleukin-6 and chronic inflammation. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006; 8:Suppl 2. S3.

10. Kasperska-Zajac A, Brzoza Z, Rogala B. Plasma concentration of interleukin 6 (IL-6), and its relationship with circulating concentration of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S) in patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria. Cytokine. 2007; 39:142–146.

11. Lin RY, Trivino MR, Curry A, Pesola GR, Knight RJ, Lee HS, Bakalchuk L, Tenenbaum C, Westfal RE. Interleukin 6 and C-reactive protein levels in patients with acute allergic reactions: an emergency department-based study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2001; 87:412–416.

12. Papanicolaou DA, Wilder RL, Manolagas SC, Chrousos GP. The pathophysiologic roles of interleukin-6 in human disease. Ann Intern Med. 1998; 128:127–137.

13. Tedeschi A, Lorini M, Suli C, Asero R. Serum interleukin-18 in patients with chronic ordinary urticaria: association with disease activity. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007; 32:568–570.

14. Ibrahim SA, Khalifa NA. Interleukin-18 correlates with disease severity in chronic autoimmune urticaria. Egypt Dermatol Online J. 2009; 5:1.

15. Kurt E, Aktas A, Aksu K, Keren M, Dokumacioglu A, Goss CH, Alatas O. Autologous serum skin test response in chronic spontaneous urticaria and respiratory diseases and its relationship with serum interleukin-18 level. Arch Dermatol Res. 2011; 303:643–649.

16. Nettis E, Dambra P, Loria MP, Cenci L, Vena GA, Ferrannini A, Tursi A. Mast-cell phenotype in urticaria. Allergy. 2001; 56:915.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download