Abstract

It has been well known that mesalazine can cause the interstitial lung disease, such as Bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia (BOOP), Non-Specific Interstitial Pneumonia (NSIP), or eosinophilic pneumonia. 5-Aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), mesalazine, and sulfasalazine are important drugs for treating inflammatory bowel disease. Topical products of these limited systemic absorption and have less frequent side effects, therefore suppository form of these drugs have been used more than systemic drug. Most cases of measalzine-induced lung toxicity develop from systemic use of the drug. A 30-year-old woman had an interstitial lung disease after using mesalazine suppository because of ulcerative colitis. The lung biopsy demonstrated eosinophilic pneumonia combined with BOOP. She was recovered after stopping of mesalazine suppository and treatment with systemic steroid.

Mesalazine and sulfasalazine are important drugs for treating inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Adverse effects of mesalazine include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, rash, fever, and hepatic dysfunction. The incidence rate of adverse effects is 3%, but most cases are not serious [1-3]. There have been many reports of interstitial lung disease (ILD) induced by sulfasalazine or mesalazine for treating IBD [4, 5]. Sulfasalazine and mesalazine can cause problems in the lung, such as Bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia (BOOP), Non-Specific Interstitial Pneumonia (NSIP), or eosinophilic pneumonia, although it has been known that there are associations between IBD and lung involvement [6]. Most cases of mesalazine or sulfasalazine-induced lung toxicity develop from systemic use of the drugs. There were limited reports that lung toxicity associated with using of suppository form of mesalazine. We report a patient with eosiophilc pneumonia combined with BOOP that developed after using mesalazine suppository.

A 30-year-old woman presented with cough that was aggravated at night for 10 days. She had ulcerative colitis and had undergone a left hemi-colectomy with a colostomy 7 weeks ago. She had received a mesalazine suppository (1 g/day) for 19 days after the operation. At the time of presentation, the patient complained of fatigue, general weakness, myalgia, cough, and a small amount of non-purulent sputum. A chest X-ray and high resolution computed tomography showed peripheral patchy consolidations with interlobular septal thickening in both lungs. Blood eosinophils were 24.5%, level of total IgE was 169 KU/L and specific IgE for dust mites were 3+ in UniCAP system. Total cell count was 31.5 × 105 cell/mL with 73.2% macrophages, 19.6% neutrophils, 1.6% eosinophils, 0% lymphocytes in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Tests for nine respiratory associated viruses (adenovirus; Rous sarcoma virus; rhinovirus; metapneumovirus; seasonal influenza A and B; parainfluenza virus 1, 2, and 3; and novel H1N1 virus) were all negative by real-time PCR. Test results for antinuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor, anti-ds DNA antibody, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody were negative. The lung biopsy demonstrated that a patchy interstitial and intra-alveolar histiocytic infiltration was admixed with many eosinophils and some neutrophils and foci of organizing fibrosis, suggestive of eosinophilic pneumonia and BOOP (Fig. 1). The mesalazine suppository was stopped. She was treated with 500 mg methylprednisolone intravenously for 3 days followed by 30 mg prednisolone orally. She recovered completely.

Sulfasalazine or mesalazine for treating IBD has been known to be associated with development of ILD [4, 5]. This issue is open to dispute. Because these drugs can cause problems in the lung, such as BOOP, NSIP, or eosinophilic pneumonia, some ILDs are similar to those seen in patients with IBD unexposed to drugs [6]. Lung involvement with IBD as a part of the extra-intestinal manifestations of IBD is not common, and the incidence rate is only 0.4% [7]. In this case, no lesion was found in the mid and lower lung areas on an abdominal computed tomography scan that was performed at the time of IBD evaluation, before the operation, although the whole lung condition was not shown.

The incidence of mesalazine-associated lung disease is unknown but appears to be low. A study of 1,700 mesalazine treated patients had a 3%-20% incidence of adverse effects and did not include any patients with pulmonary complications [2, 3].

When the drug was administrated orally, the mean age of sulfasalazine-induced lung toxicity patients was 48.3 years. Dose-dependent lung toxicity was not defined. The daily dose of sulfasalazine ranged from 1 to 8 g, with a mean of 3 g. The average duration of exposure to sulfasalazine was 17.8 months [1].

Most cases of mesalazine or sulfasalazine-induced lung toxicity developed from systemic use of the drugs. In this case, mesalazine was used as a suppository and the patient had never been exposed to mesalazine or other 5-Aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) before. The dose of mesalazine suppository was 1 g/day, and the duration of use was only 19 days. The dosage and duration are thought to be smaller and shorter for inducing lung toxicity than when the drugs are used systemically. It is also uncertain whether the lung lesions in this patient were side effects of the drug or hypersensitivity reactions.

The mechanisms of pharmacologic effect of mesalazine has been thought to block the production of interleukin-1 (IL-1), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and inhibit nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activation. The pathogenesis of mesalazine-induced lung injury is unknown, but four mechanisms are considered as a causes of drug induced lung injury; 1) oxidant injury by a drug, such as nitrofurantoin ingestion; 2) direct cytotoxic effect on alveolar capillary endothelial cells; 3) injury mediated by deposition of phospholipids within the cell; and 4) immune-mediated injury causing clinical symptoms of systemic lupus erythematosus. Currently, it is postulated that mesalazine causes immune-mediated alveolitis as evidenced by lymphocyte stimulation [2, 5, 8].

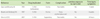

It has not been known the incidence rate of hypersensitivity reaction after using 5-ASA suppository form including mesalazine and sulfasalazine. We failed to find a case concerning the side effects or hypersensitivity reactions in the lung after using a mesalazine suppository. Only three cases are available that reported side effects after using topical 5-ASA [9-11]. Two cases were the development of pancreatitis caused by 5-ASA enema [9] or suppository [10] and the other was a case of fever and skin rash by 5-ASA enema [10] (Table 1). The cases of pancreatitis were thought be associated with form of administration. The best indicator of mesalazine's release and subsequent action in the bowel is unknown. Administrating mesalazine as an enema or suppository, effectively bypassing the threat of small bowel absorption [12]. Mesalazine has a lower absorption rate after rectal administration compared to oral administration (10% vs. 35%, respectively) [13, 14]. Because of this, the incidence of systemic side effect of the administration of suppository mesalazine is lower than other form of intake. The common side effects are dizziness (3%), rectal pain (2%), fever, rash, acne, and colitis (1% each) [15].

We didn't try to administration of mesalazine to the patient for confirm, because the condition of patient was serious at time of diagnosis. Suppository has been thought to be safer than systemic administration, even some adverse effects reported. This is a first report that a patient who experienced lung involvement to mesalazine suppository.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

(A) Many chronic inflammatory cells (predominantly macrophages) and some aggregation of eosinophils are seen. (B) Interstitial thickenings with chronic inflammatory cells infiltration and intraluminal young fibroblastic polyps, that are consistent with Bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia, are also seen.

References

1. Parry SD, Barbatzas C, Peel ET, Barton JR. Sulphasalazine and lung toxicity. Eur Respir J. 2002. 19:756–764.

2. Foster RA, Zander DS, Mergo PJ, Valentine JF. Mesalamine-related lung disease: clinical, radiographic, and pathologic manifestations. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2003. 9:308–315.

3. Brimblecombe R. Mesalazine: a global safety evaluation. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1990. 172:66.

4. Salerno SM, Ormseth EJ, Roth BJ, Meyer CA, Christensen ED, Dillard TA. Sulfasalazine pulmonary toxicity in ulcerative colitis mimicking clinical features of Wegener's granulomatosis. Chest. 1996. 110:556–559.

5. Tanigawa K, Sugiyama K, Matsuyama H, Nakao H, Kohno K, Komuro Y, Iwanaga Y, Eguchi K, Kitaichi M, Takagi H. Mesalazine-induced eosinophilic pneumonia. Respiration. 1999. 66:69–72.

7. Carter MJ, Lobo AJ, Travis SP. IBD Section, British Society of Gastroenterology. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2004. 53:Suppl 5. V1–V16.

8. Sviri S, Gafanovich I, Kramer MR, Tsvang E, Ben-Chetrit E. Mesalamine-induced hypersensitivity pneumonitis. A case report and review of the literature. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997. 24:34–36.

9. Isaacs KL, Murphy D. Pancreatitis after rectal administration of 5-aminosalicylic acid. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1990. 12:198–199.

10. Kim KH, Kim TN, Jang BI. A case of acute pancreatitis caused by 5-aminosalicylic acid suppositories in a patient with ulcerative colitis. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2007. 50:379–383.

11. Borum ML, Ginsberg A. Hypersensitivity to 5-ASA suppositories. Dig Dis Sci. 1997. 42:1076–1078.

12. Qureshi AI, Cohen RD. Mesalamine delivery systems: do they really make much difference? Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2005. 57:281–302.

13. Aumais G, Lefebvre M, Tremblay C, Bitton A, Martin F, Giard A, Madi M, Spénard J. Rectal tissue, plasma and urine concentrations of mesalazine after single and multiple administrations of 500 mg suppositories to healthy volunteers and ulcerative proctitis patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003. 17:93–97.

14. Williams CN, Haber G, Aquino JA. Double-blind, placebo-controlled evaluation of 5-ASA suppositories in active distal proctitis and measurement of extent of spread using 99mTc-labeled 5-ASA suppositories. Dig Dis Sci. 1987. 32:71S–75S.

15. Physicians' desk reference. 2004. 58th ed. Montvale, NJ: Thomson PDR;795–796.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download