Abstract

Background

There are little objective data regarding the optimal practice methods of bathing, although bathing and the use of moisturizers are the most important facets to atopic dermatitis (AD) management.

Methods

Ninety-six children with AD were enrolled during the summer season. Parents were educated to bathe them once daily with mildly acidic cleansers, and to apply emollients for 14 days. Parents recorded the frequency of bathing and skin symptoms in a diary. Scoring AD (SCORAD) scores were measured at the initial and follow-up visits. Patients were divided into two groups, based on the compliance of bathing; poor compliance was defined as ≥ 2 bathless days.

Atopic dermatitis (AD), a chronic inflammatory skin disease, is one of the most common disorders in children with a worldwide prevalence of 8-20% [1, 2]. The mechanism for the development of AD involves skin barrier dysfunction as well as immunologic alterations such as Th1/Th2 polarization [3]. Supportive or basic treatments of AD include application of emollients, proper bathing, dietary management, and avoidance of triggering factors [2, 4, 5]. When these supportive measures fail to control the disease exacerbation, therapeutic agents, such as topical corticosteroids (TCS), antibiotics and immunomodulating agents, might be indicated in a stepwise fashion [2, 5, 6].

Most guidelines for AD stress the importance of basic skin care such as proper application of moisturizers and bathing/showers [2, 4, 7, 8]. The Korean guideline for AD recommends that patients should bathe using mildly acidic soaps once daily, for several minutes in warm water, and immediately apply emollients after bathing [7]. Epidermal barrier impairment in AD patients can contribute to the penetration of allergens and antigens through the skin [9]. Mild syndets with an adjusted pH value (acidified to pH 5.5-6.0) should be used for cleansing, because the use of neutral-to-alkaline soaps can lead the precipitation of AD through barrier-dependent increases in pH and serine protease activity [10, 11]. Therefore, regular showers using weakly acidic pH soaps might be beneficial for the practical management of AD by the removal of infectious organisms, irritants or allergens.

However, a previous study has found that appreciable numbers of AD patients do not use soap or apply emollients after a bath/shower [12]. More than half of the AD patients or their guardians did not have knowledge of the benefits of everyday bathing before an education program [13]. Moreover, all patients who avoided soap and cleansers to areas of eczema thought these measures to be helpful to subjective skin symptoms [14].

There are little objective data regarding the optimal practice methods of bathing, although bathing and the use of moisturizers are the most important facets to AD management [15]. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate whether skin condition would improve when patients with AD followed general guidelines of bathing without TCS during the summer season.

From July to August in 2010, 96 patients (54 boys and 42 girls) were recruited from a pediatric allergy clinic in Chung-Ang University Hospital. Their ages ranged from 1-13 years, with the mean ± standard deviation age of 4.7 ± 2.3 years. AD was diagnosed by Hanifin and Rajka's criteria [16], and the severity was evaluated by the SCORing AD (SCORAD) (range 0-103) [17].

The patients were examined at the first visit and 14 days after the beginning of the study. At the first visit, the SCORAD score and transepidermal water loss (TEWL) were obtained by the same pediatric allergist (JK). The SCORAD score comprises objective and subjective scores [17]. The objective score takes into account the extent and the severity of AD lesions, such as erythema, edema/papulation, oozing/crust, excoriation, lichenification, and dryness. The subjective score includes the evaluation of pruritus and insomnia using a visual analogue scale that ranges from 1-10. TEWL was measured using a Vapometer® (Delfin Technologies Ltd, Kuopio, Finland). Participants were asked to complete a questionnaire eliciting basic demographic information, such as parental education and monthly income.

Parents were educated by pediatricians and trained nurses to bathe once daily from 10-15 minutes in warm (not hot) water with a mildly acidic cleanser (Physiogel®; Stiefel, Offenbach, Germany). They were also taught to wash the cleanser out completely, with no remaining soap bubbles, and not to rubbing off dirt. After bathing, the parents were instructed to dry by dabbing with towels and to apply emollients (Physiogel lotion®, Stiefel, Offenbach, Germany) within 3 minutes of towel drying. Additionally, parents were asked to apply the emollient 2-3 times a day and avoid irritants, TCSs were not allowed during the study period.

The parents were asked to record in a diary their child's symptoms and frequency of bathing, as well as the application of a moisturizer on a daily basis. The symptoms included skin lesion, pruritus, and insomnia with grading on an 11-point visual analogue scale (0-10). At the follow-up after 14 days, the symptom diary was reviewed. Based on the compliance of bathing, according to the symptom diary, the participants were divided into group A (good compliance) and group B (poor compliance, defined as ≥ 2 bathless days during the follow-up period).

This study was approved by the institutional review board at Chung-Ang University Hospital in Seoul, and written informed consent was obtained from all the parents prior to participation in this study.

Data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows version 13.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). The data are shown as the mean ± standard deviation. The Chi-squared test was applied to determine the differences in the proportions. The paired t-test was performed to examine the differences in SCORAD scores, TEWL, and subjective scores between the first and second visits in each group. In addition, Student's t-test was conducted to evaluate the means of differences of the scores and measurements. A p value < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

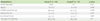

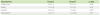

Excluding 15 patients for whom daily symptom diary information was not recorded or who applied moisturizers less than once a day, 81 patients (48 boys and 33 girls) completed this study. Group A comprised 60 participants (34 boys and 26 girls, mean age 3.9 ± 3.2 years) and Group B comprised 21 participants (14 boys and 7 girls, mean age 6.1 ± 3.6 years). There was no difference in gender, SCORAD score, itching, insomnia, and TEWL at the first visit (Table 1). Patients in group B were older than those in group A (p = 0.008).

The mean number of moisturizers that the patients used during the follow-up period was 2.3 ± 1.0 in group A and 2.1 ± 0.4 in group B, which was not significant (p = 0.079). The mean number of bathing per day was 1.2 ± 0.3 in group A and 0.8 ± 0.1 in group B (p < 0.001). There was a significant improvement of SCORAD score, itching, and insomnia in group A (all p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). Itching was significantly decreased compared to the first visit in group B (p = 0.012), while there were no differences in SCORAD score and insomnia (p = 0.595 and 0.067). However, no change in TEWL between the first and second visits was noted in both groups. The mean change in SCORAD score from the baseline at follow-up visit was observed to be greater in group A than that in group B (p = 0.038) (Table 2). However, there were no significant differences in the change of itching, insomnia, and TEWL between groups A and B.

There is a lack of objective evidence about the effects of bathing or showering in AD patients, although some guidelines or clinicians recommend daily bathing for several minutes in warm water with immediate application of an emollient [7, 18, 19]. AD guidelines have not provided coherent opinions regarding optimal bathing methods. An international consensus conference and the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence did not discuss bathing, and the Practical Allergy (PRACTALL) guideline did not recommend the frequency of bathing [11, 20, 21]. The present study demonstrated that daily bathing using weakly acidic soap had beneficial effects in reducing the clinical severity of pediatric AD in the summer season, suggesting the positive role of this bathing approach.

Bathing and shower improve hygiene, hydration, and integrity of the skin [22, 23]. In particular, the use of soap can remove various irritants including colonized microorganisms as well as sweat and dust [24]. The skin of AD patients is mostly colonized by Staphylococcus aureus, due to a combination of processes, which include defective skin barrier function, loss of innate antibacterial activities from changes in antimicrobial peptide levels, or reduced immune responses necessary for eradication and defense against bacteria, as well as changes in the skin surface pH values toward alkalinity [25]. S. aureus produces exotoxins with superantigenic properties, which may also act as allergens leading to an induction of exotoxin-specific IgE antibodies in the skin of patients with AD [26]. Some attempts have been made to suppress the growth of S. aureus as an important treatment of AD, because of the deleterious effects of the bacteria [27-29]. For example, gentian violet and intranasal mupirocin with dilute bleach baths, which can decrease S. aureus density, have been reported to lessen AD severity [28, 29]. It is possible that regular bathing with weakly acidic syndets showed clinical effects on AD skin by reducing S. aureus colonization, although the growth of these bacteria was not measured in this study.

Our results are consistent with those of a previous study by Mochizuki et al. [30], who reported an improvement of skin symptoms in elementary school children with AD using a skin care program including a shower therapy in the summer season. Our study was also conducted in only the summer season to exclude the influence of seasonal variation. In addition, it was expected that the use of moisturizers had less of an effect on the study results because humidity is high during the summer months. Mochizuki et al. [30] examined the effects of showers with plain water and reported a significant improvement of the skin lesions in AD patients. The possibility that plain water removes irritants or contributes to skin hydration cannot be excluded. The effect of soap could be evaluated if patients were assigned to another arm, in which they were instructed not to use soaps. However, we did not compare the clinical improvement between bathing with and without soap, because there was a general consensus among the previous reports about the need for the use of weakly acidic soap, in terms of skin barrier disruption of AD [10, 11].

A previous study reported that bathing, followed by emollient application, can increase the hydration status in AD patients, while bathing without the use of moisturizer decreases skin hydration [31]. In that study, emollient alone produced greater hydration than bathing with immediate emollient [31]; however, the authors did not evaluate the effect of these bathing methods on clinical symptom scores. The present study did not show a significant difference in TEWL between regular bathing group and the poorly compliant group. Therefore, regular bathing in the proper way can contribute to the increase of skin hydration and the improvement of clinical symptoms.

There was also an improvement of the itching score in the group with poor compliance to bathing during the follow-up period, which may be due to better compliance with other skin care, such as the avoidance of irritants and the use of moisturizers. However, improvement of SCORAD and subjective symptoms in group A was higher than that of group B, which suggests that the combination with skin hydration and bathing is more effective than using the emollients alone. Nevertheless, the possibility exists that the difference in skin hydration between both groups affects AD severity, because the number of moisturizers patients used were lower in group B than in group A, without statistical significance. Our study also has other limitations mostly stemming from its study design and the definition of groups. This is an observational study, and sample size was not determined based on power and significance levels before the enrollment of subjects. In addition, the definition of poor compliance was arbitrary, because there have been few studies that focused on the frequency of the bathing or showering in AD patients. However, it is noteworthy that there are few clinical trials supporting the usefulness of proper bathing in AD patients reasonably.

In conclusion, daily bathing using weakly acidic syndets with immediate application of an emollient can reduce skin symptoms in pediatric patients with AD during the summer season. Therefore, it is necessary to educate patients and their parents regarding the proper skin care, including regular bathing. Further research is needed to investigate the effect of this bathing method on AD lesions in other seasons.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1SCORAD score, subjective scores, and transepidermal water loss between initial and follow-up visits (*p < 0.01, †p < 0.05). |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by Cj CheilJedang (seoul, korea) and the ministry of environment of korea.

References

1. Williams H, Stewart A, von Mutius E, Cookson W, Anderson HR. International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Phase One and Three Study Groups. Is eczema really on the increase worldwide? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008. 121:947–954.e15.

2. Lee SI, Kim J, Han Y, Ahn K. A proposal: Atopic Dermatitis Organizer (ADO) guideline for children. Asia Pac Allergy. 2011. 1:53–63.

3. Maintz L, Novak N. Getting more and more complex: the pathophysiology of atopic eczema. Eur J Dermatol. 2007. 17:267–283.

4. Carbone A, Siu A, Patel R. Pediatric atopic dermatitis: a review of the medical management. Ann Pharmacother. 2010. 44:1448–1458.

7. The Korean Academy of Pediatric Allergy and Respiratory Disease. Guideline of atopic dermatitis in Korean children. 2008. 1st ed. Seoul: Kwangmun Press;3–55.

8. Eichenfield LF, Hanifin JM, Luger TA, Stevens SR, Pride HB. Consensus conference on pediatric atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003. 49:1088–1095.

9. Boralevi F, Hubiche T, Léauté-Labrèze C, Saubusse E, Fayon M, Roul S, Maurice-Tison S, Taïeb A. Epicutaneous aeroallergen sensitization in atopic dermatitis infants - determining the role of epidermal barrier impairment. Allergy. 2008. 63:205–210.

10. Elias PM, Hatano Y, Williams ML. Basis for the barrier abnormality in atopic dermatitis: outside-inside-outside pathogenic mechanisms. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008. 121:1337–1343.

11. Akdis CA, Akdis M, Bieber T, Bindslev-Jensen C, Boguniewicz M, Eigenmann P, Hamid Q, Kapp A, Leung DY, Lipozencic J, Luger TA, Muraro A, Novak N, Platts-Mills TA, Rosenwasser L, Scheynius A, Simons FE, Spergel J, Turjanmaa K, Wahn U, Weidinger S, Werfel T, Zuberbier T. European Academy of Allergology. Clinical Immunology/American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology/PRACTALL Consensus Group. Diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in children and adults: European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology/American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology/PRACTALL Consensus Report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006. 118:152–169.

12. Hon KL, Leung TF, Wong Y, So HK, Li AM, Fok TF. A survey of bathing and showering practices in children with atopic eczema. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005. 30:351–354.

13. Yum HY, Han KO, Park JA, Kang MY, Chang SI, Cho SH, Pyun BY, Rha YH, Kim KH, Yoon HJ, Kim WK, You KH, Cho YJ. Improvement in disease knowledge through an education program of atopic dermatitis. Korean J Asthma Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012. 32:21–25.

14. Burkhart CG. Clinical assessment by atopic dermatitis patients of response to reduced soap bathing: pilot study. Int J Dermatol. 2008. 47:1216–1217.

15. Chamlin SL, Frieden IJ, Fowler A, Williams M, Kao J, Sheu M, Elias PM. Ceramide-dominant, barrier-repair lipids improve childhood atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2001. 137:1110–1112.

16. Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1980. 92:44–47.

17. Kunz B, Oranje AP, Labrèze L, Stalder JF, Ring J, Taïeb A. Clinical validation and guidelines for the SCORAD index: consensus report of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatology. 1997. 195:10–19.

18. Lynde C, Barber K, Claveau J, Gratton D, Ho V, Krafchik B, Langley R, Marcoux D, Murray E, Shear N. Canadian practical guide for the treatment and management of atopic dermatitis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2005. 8:Suppl 5. 1–9.

19. Gutman AB, Kligman AM, Sciacca J, James WD. Soak and smear: a standard technique revisited. Arch Dermatol. 2005. 141:1556–1559.

20. Ellis C, Luger T, Abeck D, Allen R, Graham-Brown RA, De Prost Y, Eichenfield LF, Ferrandiz C, Giannetti A, Hanifin J, Koo JY, Leung D, Lynde C, Ring J, Ruiz-Maldonado R, Saurat JH. ICCAD II Faculty. International Consensus Conference on Atopic Dermatitis II (ICCAD II): clinical update and current treatment strategies. Br J Dermatol. 2003. 148:Suppl 63. 3–10.

21. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Atopic eczema in children: management of atopic eczema in children from birth up to the age of 12 years. accessed 2012 Jul 25. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence;Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/CG057.

22. Krakowski AC, Eichenfield LF, Dohil MA. Management of atopic dermatitis in the pediatric population. Pediatrics. 2008. 122:812–824.

23. Walling HW, Swick BL. Update on the management of chronic eczema: new approaches and emerging treatment options. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2010. 3:99–117.

24. Rönner AC, Berland CR, Runeman B, Kaijser B. The hygienic effectiveness of 2 different skin cleansing procedures. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2010. 37:260–264.

26. Langer K, Breuer K, Kapp A, Werfel T. Staphylococcus aureus-derived enterotoxins enhance house dust mite-induced patch test reactions in atopic dermatitis. Exp Dermatol. 2007. 16:124–129.

27. Gauger A, Mempel M, Schekatz A, Schäfer T, Ring J, Abeck D. Silver-coated textiles reduce Staphylococcus aureus colonization in patients with atopic eczema. Dermatology. 2003. 207:15–21.

28. Huang JT, Abrams M, Tlougan B, Rademaker A, Paller AS. Treatment of Staphylococcus aureus colonization in atopic dermatitis decreases disease severity. Pediatrics. 2009. 123:e808–e814.

29. Brockow K, Grabenhorst P, Abeck D, Traupe B, Ring J, Hoppe U, Wolf F. Effect of gentian violet, corticosteroid and tar preparations in Staphylococcus-aureus-colonized atopic eczema. Dermatology. 1999. 199:231–236.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download