Abstract

Eosinophilic esophagitis is a chronic inflammatory disease of the esophagus, immune/antigens mediated, whose incidence is increasing both in adults and pediatric population. It is clinically characterised by symptoms related to esophageal dysfunction and associated with eosinophil-predominant esophageal inflammation. The role of atopy has been clearly demonstrated both in epidemiological and experimental studies and has important implications for diagnosis and therapy. In fact, many evidences show that food and inhalant allergens represent the most important factors involved in the progress of the disease. Several studies have reported that, in a range between 50 and 80%, patients with eosinophilic esophagitis have a prior history of atopy, and for them, the presence of allergic rhinitis, asthma or atopic dermatitis is frequent. Skin tests are able to identify in most patients the allergens involved, allowing a correct dietary approach in order to achieve the remission of symptoms and the biopsy normalization.

Eosinophilic Esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the esophagus with immune-allergic pathogenesis and clinical manifestations characterized by the occurrence of acute symptoms correlated to esophagus dysfunction alternated with remission of the disease. Its prevalence is about 4/10,000 inhabitants, whereas its incidence, higher in male than in female (3:1), is approximately 1/10,000 inhabitants/year. It can occur at any age and no difference on the incidence was demonstrated between paediatric and adult population. In adults the diagnosis is more frequent from the age of 30 to 40 years. Recently, a progressive incidence increase has been highlighted, both in adult and paediatric population [1, 2]. EoE is classified in two forms, the primitive and the secondary. The primitive form belongs to a group of gastrointestinal diseases associated to eosinophilic inflammation in absence of other known causes. The secondary form may result as a consequence of various conditions such as gastroesophageal reflux disease, parasitic infections, and Crohn's disease. Described for the first time in 1977 [3], the primitive form is histopathologically characterized by the presence of isolated eosinophilic inflammation of the esophagus without involvement of other sections of the gastro-intestinal tract.

The diagnosis is based on the presence of esophageal symptoms and/or the upper gastrointestinal tract involvement, associated with the presence, with few exceptions, of a number equal or greater than 15 eosinophils/HPF, in at least 5 esophageal biopsies [4]. To assess the diagnosis of EoE it is required to prove the non existence of gastroesophageal reflux disease through pH-metry at the baseline and/or failure of treatment with PPI for at least two months.

The pathogenic role of atopy was clearly demonstrated in both epidemiological and experimental studies with important diagnostic and therapeutic implications. EoE is associated with atopy in 50-80% of cases. Most patients presented sensitization to food, inhalant allergens, or both, diagnosed by skin prick test (SPT) and/or in vitro specific IgE assay. The presence of an IgE-mediated hypersensitivity to food antigens is estimated in 15-43% of patients. In patients with EoE, a history of allergic rhinitis appears in 40-75% of cases. Association with asthma and atopic dermatitis is observed in 14-70% and 4-60% of patients, respectively [5, 6].

The histopathologic assessment of the esophagus in patients with EoE clearly illustrates a phenotype similar to other inflammatory allergic diseases. Actually, eosinophils, mast cells, T lymphocytes and basophils are detectable at the epithelial level with an increased degree of subepithelial tissue remodeling [7, 8]. In particular, through immunohistochemistry, an increase in the number of mast cells was revealed in patients affected by EoE compared to controls [9]. These cells contribute to tissue inflammation by producing cytokines that induce eosinophils activation and esophageal remodeling. Chronic inflammation leads to a thickening of the mucosa, submucosa and the tunica muscularis propria, leading first to the remodelling and subsequently to fibrosis, with collagen accumulation in the mucosa and the basal membrane, as demonstrated in some ultrastructural studies [10]. In addition, most of these cells show an activated phenotype with evidence of eosinophils, mast cells and basophils degranulation [7].

An increased level of Th2-type cytokines, IL-5 and IL-13, has been reported in the esophagus in patients with EoE [11]. Both these cytokines play an important role in disease pathogenesis. In a murine model of EoE, IL-5 was capable to promote traffic of eosinophils to the esophageal mucosa [12]. In vitro, epithelial cells stimulation with IL-13 induces high levels of eotaxin-3 correlated with the severity of esophageal eosinophilia. Moreover IL-15 activates CD4+ T cells to produce cytochines that act on eosinophils and therefore is implicated in their recruitment in the esophagus. In humans, an increase of IL-15 and its receptor (IL-15R) at the tissue, correlates with the eosinophilia in the mucosa. In animal models of EoE, the deletion of the gene for IL-15R seems to protect from eosinophilic infiltration [13].

Despite the high incidence of IgE-mediated sensitization to food allergens found in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis, only a minority of them develop anaphylaxis after food intake. The immunologic mechanism behind that remains unclear. However, it has been revealed that patients with gastrointestinal eosinophilia have a predominance of IL-5-positive Th2 responsive to peanut allergens, while in patients with peanut anaphylaxis IL-5-negative allergen-specific Th2 cells are predominant [14]. The clinical differences between food-induced anaphylaxis and eosinophilic diseases of the gastrointestinal tract are associated with different Th2-cell response.

Another in vitro study has evaluated the response of mononuclear cells from peripheral blood in patients with active EoE in response to specific allergen stimulation, compared to healthy controls. Mononuclear cells of 15 patients with EoE were incubated with food (cow's milk, egg, soy, peanut and wheat) and inhalant allergens (dust mites, Aspergillus fumigatus, Alternaria alternata, and ragweed pollen). Compared to healthy controls, significantly higher levels of IL-5 and IL-13 in response to various allergens were detected, even in the absence of a evident IgE-mediated sensitization [15].

Inhalant allergens seem to play an important role in pathogenesis of EoE disease. In a murine animal model, intranasal exposure to inhalant allergen (A. fumigatus) in sensitized animals induced marked esophagus eosinophilia, eosinophils degranulation and epithelial hyperplasia, very similar to the findings in humans [16]. Afterwards, a study performed in patients with seasonal respiratory allergy has established the presence of esophageal eosinophilic infiltration in association with seasonal symptoms [17]. Moreover, in a case report of a patient affected by EoE associated with allergic rhinitis, bronchial asthma and symptoms exacerbation during the pollen season, biopsies obtained during the pollen season demonstrated moderate to severe esophagus eosinophilic infiltration, while in winter esophageal biopsies showed only a mild infiltrate in absence of eosinophils [18]. Moreover, a seasonal distribution of new diagnoses of EoE is also demonstrated. A retrospective study in adults showed a significant prevalence of new diagnoses in April and May when compared to the other months of the year. These data confirm the presence of a seasonal variation of diagnosis of EoE described as well in paediatric patients [19, 20].

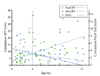

A complete patients profile assessment, analysing the sensitization using SPT to common inhalant and food allergens and patch test for food allergens (Atopy Patch Test, APT), illustrated an increase of sensitization to aeroallergens, in particular after the age of 4 years in patients with EoE, and a decrease of sensitization to food allergens with increasing age [21] (Fig. 1). These differences, although not specific for EoE, are correlated with patient age and have important therapeutic implications, suggesting a predominant role of food allergens in children.

EoE has been described, in patients suffering from food allergy, as a possible complication in the course of induction of oral tolerance to allergens of the egg and milk proteins [22, 23]. A retrospective analysis in paediatric population affected by EoE undergoing elimination from the diet of the 6 most common allergens (see below), has allowed us to identify the foods most frequently responsible to esophagus inflammation. Foods most commonly involved are cow's milk (74%), wheat (26%), egg (17%), soy (10%) and peanut (6%) [24]. For these reason all patients, both adults and children, must undergo SPT in order to reveal sensitization to inhalant and food allergens. Positive skin and serological tests for these allergens are frequent in the majority of patients and a symptoms improvement is reported after removal of the allergen.

Indeed, dietary treatment was demonstrated to be effective in paediatric patients with EoE and concomitant food allergy. Dietary interventions in children allow to attain high rates of clinical and histological response. Three types of diet resulted successful: (i) the substitution of all solid food with a blend of nutritionally complete protein sources entirely composed of synthetic amino acids (elementary diet); (ii) the elimination of the 6 most common food allergens (milk and products, eggs, wheat, soybeans, peanuts, fish/shellfish); (iii) the abolition of specific foods after positive prick test and medical history.

The first study that investigated the relationship between food allergy and EoE, evaluated 10 children with symptomatic EoE and subjected to elemental diet for at least 6 weeks. In 8 of these patients a complete remission of symptoms was achieved and the remaining 2 patients reported symptoms improvement with eosinophilia resolution [25]. These data were then confirmed on a larger sample of 51 paediatric patients who underwent the same dietary intervention. In 49 patients a rapid symptoms' improvement with a significant decrease of esophageal eosinophilia within 4 weeks (33.7 ± 10.3 to 1.0 ± 0.6 eosinophils/HPF) was observed [26].

The elimination of the 6 most common food allergens was resulted to induce an improvement of both symptoms (in 74% of cases) and eosinophilic infiltration (from 80.2 ± 44.0 to 13.6 ± 23.8 eosinophils/HPF), however lower than the elemental diet in paediatric patients [27].

Starting from the recognition of a IgE and non-IgE mediated hypersensitivity to food allergens, the effectiveness of a diet based on the elimination of food "triggers" identified by SPT and APT has been evaluated.

In a paediatric population, 26 patients followed a diet, for at least 6 weeks, without the food(s) to which they have had a positive result by SPT and APT, obtaining a resolution of symptoms in 69% of cases and a reduction in esophageal eosinophilic infiltration from 55.8 ± 24.6 to 8.4 ± 8.4 eosinophils/HPF [28]. In this sample, patients frequently resulted positive to SPT to cow's milk, egg, peanut, shellfish, peas, fish, rye, tomato and wheat. The most frequently positive APT were wheat, corn, beef, cow's milk, soy, rye, chicken, oat and potatoes.

However, the choice of the diet should also take into account the impact on quality of life of the child and the need to increase parents and relatives commitment through proper education. The elemental diet is in fact scarcely palatable with consequent need of using the nasogastric tube. On the other hand, a restrictive diet can also be difficult to implement. In adults the importance of diet has not yet been fully demonstrated, confirming the limited correlation in adults, between EoE and food allergy. In 6 adults with EoE and positivity of the SPT and/or specific IgE for wheat and rye (and also to aeroallergens), a diet free of these foods did not produce a significant reduction of the number of esophageal eosinophils neither an improvement of symptoms [29]. According to the authors, this result could not be explained with the importance of the food allergens in the pathogenesis of EoE because their extracts cross-react with sensitizing pollen allergens. However, more recently, an effective diet even in adults seems to emerge. Diet without the 6 most common food allergens in a group of 50 adult patients showed a significant improvement in symptoms and esophageal eosinophilia (from 34 to 8 eosinophils / HPF in the oesophagus and proximal 48 to 13 eosinophils / HPF distal oesophagus) with return to baseline after food reintroduction [30]. Further studies are needed to determine the role of the elimination diet in adults. However these patients, for the predominant role of inhalant allergens, may benefit from a maintenance treatment during the pollen season, when a worsening of esophageal symptoms occur.

It is likely that molecular diagnosis will further improve the approach to dietary treatment in patients with EoE, especially in those patients with multiple sensitizations. The use of recombinant allergens may allow to discriminate between a true food allergy and a cross-reactivity between food and inhalant sensitization linked to common epitopes.

Beside the cornerstone of drug therapy based on steroids, in addition to dietary approach when indicated, numerous attempts have been made to increase the treatment options. To support the pathogenic role of IL-5, the therapeutic approach with mepolizumab (humanized antibody against IL-5) has led, in some adult patients with active EoE, to a significant reduction in the number of eosinophils in the mucosa but without a corresponding improvement of the clinical symptoms [31]. More recently, reslizumab has been shown to reduce intraephitelial esophageal eosinophil counts in children and adolescents with eosinophilic esophagitis; however the improvements of symptoms were not associated with changes in eosinophil counts [32]. Therefore, the clinical response to this drug should be further evaluated, especially in relation to its promising efficacy in some subgroups of patients.

In conclusion, many evidences show that food and inhalant allergens represent the main factors involved in the development of EoE. This finding highlights the importance of the allergist during the diagnostic and therapeutic phase. Skin tests are in fact able to identify in most patients the allergens involved, allowing a correct dietary approach in order to achieve the remission of symptoms and also biopsy normalization.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Correlation between skin prick test (SPT) for aeroallergens and food allergens, Atopy patch test and patient's age [21]. |

References

1. Kapel RC, Miller JK, Torres C, Aksoy S, Lash R, Katzka DA. Eosinophilic esophagitis: a prevalent disease in the United States that affects all age groups. Gastroenterology. 2008. 134:1316–1321.

2. Prasad GA, Alexander JA, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Smyrk TC, Elias RM, Locke GR 3rd, Talley NJ. Epidemiology of eosinophilic esophagitis over three decades in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009. 7:1055–1061.

3. Dobbins JW, Sheahan DG, Behar J. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis with esophageal involvement. Gastroenterology. 1977. 72:1312–1316.

4. Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, Atkins D, Attwood SE, Bonis PA, Burks AW, Chehade M, Collins MH, Dellon ES, Dohil R, Falk GW, Gonsalves N, Gupta SK, Katzka DA, Lucendo AJ, Markowitz JE, Noel RJ, Odze RD, Putnam PE, Richter JE, Romero Y, Ruchelli E, Sampson HA, Schoepfer A, Shaheen NJ, Sicherer SH, Spechler S, Spergel JM, Straumann A, Wershil BK, Rothenberg ME, Aceves SS. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011. 128:3–20.e6. quiz 21-2.

5. Roy-Ghanta S, Larosa DF, Katzka DA. Atopic characteristics of adult patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008. 6:531–535.

6. Erwin EA, James HR, Gutekunst HM, Russo JM, Kelleher KJ, Platts-Mills TA. Serum IgE measurement and detection of food allergy in pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010. 104:496–502.

7. Chehade M. Translational research on the pathogenesis of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2008. 18:145–156.

8. Chehade M, Yershov O, Shreffler W, Chen W, Wanich N, Sampson HA. Basophils are present in the esophagus of children with eosinophilic esophagitis [abstract]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008. 121:Suppl 1. S105.

9. Abonia JP, Blanchard C, Butz BB, Rainey HF, Collins MH, Stringer K, Putnam PE, Rothenberg ME. Involvement of mast cells in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010. 126:140–149.

10. Fox VL, Nurko S, Teitelbaum JE, Badizadegan K, Furuta GT. High-resolution EUS in children with eosinophilic "allergic" esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003. 57:30–36.

11. Straumann A, Bauer M, Fischer B, Blaser K, Simon HU. Idiopathic eosinophilic esophagitis is associated with a T(H)2-type allergic inflammatory response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001. 108:954–961.

12. Mishra A, Hogan SP, Brandt EB, Rothenberg ME. IL-5 promotes eosinophil trafficking to the esophagus. J Immunol. 2002. 168:2464–2469.

13. Zhu X, Wang M, Mavi P, Rayapudi M, Pandey AK, Kaul A, Putnam PE, Rothenberg ME, Mishra A. Interleukin-15 expression is increased in human eosinophilic esophagitis and mediates pathogenesis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2010. 139:182–193.e7.

14. Prussin C, Lee J, Foster B. Eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease and peanut allergy are alternatively associated with IL-5+ and IL-5(-) T(H)2 responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009. 124:1326–1332.e6.

15. Yamazaki K, Murray JA, Arora AS, Alexander JA, Smyrk TC, Butterfield JH, Kita H. Allergen-specific in vitro cytokine production in adult patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2006. 51:1934–1941.

16. Mishra A, Hogan SP, Brandt EB, Rothenberg ME. An etiological role for aeroallergens and eosinophils in experimental esophagitis. J Clin Invest. 2001. 107:83–90.

17. Onbasi K, Sin AZ, Doganavsargil B, Onder GF, Bor S, Sebik F. Eosinophil infiltration of the oesophageal mucosa in patients with pollen allergy during the season. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005. 35:1423–1431.

18. Fogg MI, Ruchelli E, Spergel JM. Pollen and eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003. 112:796–797.

19. Almansa C, Krishna M, Buchner AM, Ghabril MS, Talley N, DeVault KR, Wolfsen H, Raimondo M, Guarderas JC, Achem SR. Seasonal distribution in newly diagnosed cases of eosinophilic esophagitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009. 104:828–833.

20. Wang FY, Gupta SK, Fitzgerald JF. Is there a seasonal variation in the incidence or intensity of allergic eosinophilic esophagitis in newly diagnosed children? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007. 41:451–453.

21. Sugnanam KK, Collins JT, Smith PK, Connor F, Lewindon P, Cleghorn G, Withers G. Dichotomy of food and inhalant allergen sensitization in eosinophilic esophagitis. Allergy. 2007. 62:1257–1260.

22. Ridolo E, De Angelis GL, Dall'aglio P. Eosinophilic esophagitis after specific oral tolerance induction for egg protein. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011. 106:73–74.

23. Sánchez-García S, Rodríguez DelRío P, Escudero C, Martínez-Gómez MJ, Ibáñez MD. Possible eosinophilic esophagitis induced by milk oral immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012. 129:1155–1157.

24. Kagalwalla AF, Shah A, Li BU, Sentongo TA, Ritz S, Manuel-Rubio M, Jacques K, Wang D, Melin-Aldana H, Nelson SP. Identification of specific foods responsible for inflammation in children with eosinophilic esophagitis successfully treated with empiric elimination diet. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011. 53:145–149.

25. Kelly KJ, Lazenby AJ, Rowe PC, Yardley JH, Perman JA, Sampson HA. Eosinophilic esophagitis attributed to gastroesophageal reflux: improvement with an amino acid-based formula. Gastroenterology. 1995. 109:1503–1512.

26. Markowitz JE, Spergel JM, Ruchelli E, Liacouras CA. Elemental diet is an effective treatment for eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adolescents. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003. 98:777–782.

27. Kagalwalla AF, Sentongo TA, Ritz S, Hess T, Nelson SP, Emerick KM, Melin-Aldana H, Li BU. Effect of six-food elimination diet on clinical and histologic outcomes in eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006. 4:1097–1102.

28. Spergel JM, Beausoleil JL, Mascarenhas M, Liacouras CA. The use of skin prick tests and patch tests to identify causative foods in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002. 109:363–368.

29. Simon D, Straumann A, Wenk A, Spichtin H, Simon HU, Braathen LR. Eosinophilic esophagitis in adults--no clinical relevance of wheat and rye sensitizations. Allergy. 2006. 61:1480–1483.

30. Gonsalves N, Yang GY, Doerfler B, Ritz S, Ditto AM, Hirano I. Elimination diet effectively treats eosinophilic esophagitis in adults; food reintroduction identifies causative factors. Gastroenterology. 2012. 142:1451–1459.e1.

31. Straumann A, Conus S, Grzonka P, Kita H, Kephart G, Bussmann C, Beglinger C, Smith DA, Patel J, Byrne M, Simon HU. Anti-interleukin-5 antibody treatment (mepolizumab) in active eosinophilic oesophagitis: a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Gut. 2010. 59:21–30.

32. Spergel JM, Rothenberg ME, Collins MH, Furuta GT, Markowitz JE, Fuchs G 3rd, O'Gorman MA, Abonia JP, Young J, Henkel T, Wilkins HJ, Liacouras CA. Reslizumab in children and adolescents with eosinophilic esophagitis: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012. 129:456–463. 463.e1–463.e3.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download