Abstract

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common, chronic or chronically relapsing, severely pruritic, eczematous skin disease. AD is the second most frequently observed skin disease in dermatology clinics in Japan. Prevalence of childhood AD is 12-13% in mainland Japan; however, it is only half that (about 6%) in children from Ishigaki Island, Okinawa. Topical steroids and tacrolimus are the mainstay of treatment. However, the adverse effects and emotional fear of long-term use of topical steroids have induced a "topical steroid phobia" in patients throughout the world. Undertreatment can exacerbate facial/periocular lesions and lead to the development of atopic cataract and retinal detachment due to repeated scratching/rubbing/patting. Overcoming topical steroid phobia is a key issue for the successful treatment of AD through education, understanding and cooperation of patients and their guardians.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common, chronic or chronically relapsing, severely pruritic, eczematous skin disease. The incidence of AD is generally considered to be increasing worldwide [1, 2]. The percentage of adolescent- and adult-type AD has also been increasing [3, 4]. The etiology and pathogenesis of AD are not fully delineated. Recent studies demonstrate that it involves a complex interaction of skin barrier dysfunction, exposure to external allergens or microbes, Th2-prone response and psychosomatic reaction. Intense itching, skin inflammation, and other atopic symptoms impose a remarkable burden on the individual and society.

The history of AD is very old. Prior to the nomenclature of "atopic dermatitis" by Sulzberger et al. [5] in 1933, the disease was reported under various dermatological terms such as neurodermite diffusa (Brocq), lichen chronicus simplex disseminatus (Vidal), pruritus with lichenification, allergic eczema, hay-fever eczema and flexural eczema; each one highlighted important clinical aspects of this disease. Helmont (1607) and Trousseau (1850) pointed out a close association between asthma and certain types of pruritic skin disorder, and Vidal (1880) described a characteristic distribution of itchy lichenified plaques in this disease [5, 6]. Brocq and Jacquet (1891) referred to the disease as neurodermite diffusa, emphasizing its psychosomatic nature; later on, the disease was commonly reported in literature under the term neurodermatitis (neurodermitis) diffusa or disseminate, neurodermatitis constitutionalis, and disseminated neurodermatitis [7]. In 1892, Besnier named the disease "diathésique eczémato-lichénienne", mentioning that most cases first develop as infantile eczema with severe pruritus at predilection sites such as the face, neck, and perioral and flexural regions, and they are closely related with asthma and hay fever [5, 8]. Since then, the term "prurigo Besnier" has often appeared in literature, especially in Europe. In 1923, Coca and Cooke [9] first reported that asthma and hay fever are specifically compartmentalized in individuals or family members who were hypersensitive to various external antigens, and they proposed the use of the term "atopy" for these mysterious phenomena. Meanwhile, the close association of certain types of itchy eczema with asthma and hay fever again drew special attention by Low as an eczema-asthma-prurigo complex or by Drake as an asthma-eczema-prurigo complex in 1928 [8, 10], leading to the proposal of "atopic dermatitis/eczema" [5, 11, 12]. Even in the early 1930s, basic concepts for AD had been postulated: 1) family history of atopy; 2) antecedent infantile eczema; 3) preponderance on antecubital and popliteal fossae, anterior neck, chest, face and eyelids; 4) skin hyperpigmentation; 5) no appreciable vesicle formation as is usually clinically and histologically found in contact dermatitis; 6) unstable or hypersensitive vasomotor neuron reaction; 7) negative patch test reaction to most contact allergens; 8) positive skin test reaction to various environmental and food allergens; and 9) positive serum reaginic activity (=IgE) as detected by Prausnitz-Küstner reaction [11-13].

Genetic and environmental factors are apparently involved in the onset and exacerbation of AD in a mutually interactive manner. In 1993, Schultz Larsen et al. [14] reported that the pairwise concordance rate of AD in monozygotic twin pairs was 72% while it was only 23% in their dizygotic counterparts. They also noted that the prevalence of AD increased sharply from 3.2% in 1960-1964 to 10.2% in 1970-1974. Interestingly, the results of a similar study published in 1971 indicated that the concordance rate seemed to be affected by the prevalence rate even in genetically identical twins [15]. In the 6996 pairs of twins with a 4.3% AD prevalence rate, the pairwise concordance rate of AD was only 15.4% and 4.5% in the monozygotic and dizygotic twins, respectively [15]. AD-inducing environmental factors, as yet unknown, had increased their power in industrialized and developing countries and seemed to trigger the onset of AD in almost all individuals who were genetically predisposed to the disease.

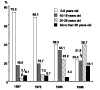

Masuda reported that the incidence of AD in outpatient clinics was 4.1% in 36,233 patients who visited the Dermatology Clinic of the University of Tokyo from 1959 to 1961. In the Branch Hospital of the University of Tokyo, the incidence of AD in our first-visit patients was 5.6% (195/3,491) in 1967, 8.7% in 1976 (277/3,188), 7.7% (224/2,913) in 1986 and 10.1% (261/2,586) in 1996 [16]. Considering the results of previous reports on the incidence of AD in dermatological outpatient clinics [2.3% (Drake, 1928, London), 0.6% (Nexmand, 1926-1935, Copenhagen), 1.4% (Nexmand, 1936-1945, Copenhagen), 0.32-1.53% (Iijima & Saito, 1938-1955, Sendai), 1.4% (Ofuji, 1954-1956, Kyoto), 7% (Hellerström & Rajka, 1953-1959, Karolinska), and 8.3% (Uehara & Ofuji, 1977, Kyoto)], AD had become a very common skin disease during the 1950s through 1970s in industrialized countries [16]. Another interesting point was the age distribution of AD patients. In 1967, 73.9% of AD patients were 0-9 years old at the Branch Hospital of the University of Tokyo, but this figure gradually dropped to 23.4% by 1996. In contrast, the percentage of AD patients 20-29 years old was 3.1% in 1967, and markedly increased to reach 38.7% by 1996 [16]. Adult-type AD patients at dermatological clinics have clearly increased recently (Fig. 1) as pointed out by Sugiura et al. [4].

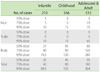

In order to clarify the current prevalence of skin disorders among dermatology patients in Japan, the Japanese Dermatological Association conducted a nationwide, cross-sectional, seasonal, multicenter study in 2007-2008 [17]. Among the 67,448 cases, the top twenty skin disorders were, in descending order of incidence, miscellaneous eczema, AD, tinea pedis, urticaria/angioedema, tinea unguium, viral warts, psoriasis, contact dermatitis, acne, seborrheic dermatitis, hand eczema, miscellaneous benign skin tumors, alopecia areata, herpes zoster/postherpetic neuralgia, skin ulcers (nondiabetic), prurigo, epidermal cysts, vitiligo vulgaris, seborrheic keratosis, and drug eruption/toxicoderma (Table 1). The incidence of AD was 9.8% without any gender difference. The age distribution of AD was biphasic, peaking at 0-5 years old and 21-35 years old (Fig. 2) [17]. Patients older than 46 years comprised 9.6% (649/6,733) of all AD patients [17].

The incidence of AD in Japanese elementary school students was around 3% in 1981-1983 but increased to around 6-7% in the 1990s [3]. Yura and Shimizu conducted a questionnaire survey of health symptoms in four million school children (aged 7-12 years) in Osaka and reported that the lifetime prevalence of AD increased from 15.0% in 1985 to 24.1% in 1993 but leveled off thereafter (22.9% in both 1995 and 1997) [18]. Their subsequent study also confirmed the consecutive decrease of AD prevalence from 1993 to 2006 (16.5%) [19]. Meanwhile, the prevalence of wheezing was constant at 3.0 ± 0.1% between 1975 and 1983, and then increased to 4.7% in 1993. It restabilized at 4.4 ± 0.3% between 1993 and 2006 [19]. The prevalence of rhinitis increased from 12.3% in 1983 to 16.7% in 1991, increased further to 25.4% in 2003, and then leveled off at 24.7% in 2006 [19]. The reported prevalence of AD of Japanese children is summarized in Table 2.

From 2000 to 2002, the research team of the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (chief researcher: Dr. S. Yamamoto) examined 48,072 children living in Asahikawa, Iwate, Tokyo, Gifu, Osaka, Hiroshima, Kochi, and Fukuoka [20]. They reported that the national average prevalence rate of AD was 12.8% in 4-month-old children, 9.8% in 18-month-olds, 13.2% in 3-year-olds, 11.8% in 6- to 7-year-olds, 10.6% in 12- to 13-year-olds, and 8.2% in 18-year-olds [20]. In 2001, we started a population-based survey of children aged 5 years and younger in Ishigaki Island, Okinawa, Japan (Kyushu University Ishigaki Dermatitis Study; KIDS). The prevalence of childhood AD in this southern subtropical island was as low as around 6% [21, 22] and did not increase during the period from 2001 to 2010 (unpublished data).

It is well documented that AD regresses spontaneously, especially in infants and children. Kawaguchi et al. [23] reported that out of 102 4-month-old patients, 83 regressed spontaneously by 18 months old. Illi et al. [24] reported that the cumulative prevalence of AD in the first 2 years of life was 21.5%. Among these children with early AD, 43.2% were in complete remission by the age of 3 years, 38.3% had an intermittent pattern of disease, and 18.7% had symptoms of AD every year. Severity (adjusted cumulative odds ratio, 5.86; 95% CI, 3.04-11.29) and atopic sensitization (adjusted cumulative odds ratio, 2.76; 95% CI, 1.29-5.91) were major determinants of prognosis of AD [24]. In our KIDS cohort, 71.6% (53/74) of AD patients under 5 years old regressed spontaneously, whereas 5.5% (44/795) of non-AD individuals developed AD during the 3-year followup. Increases in total IgE levels were greater and more rapid in children with long-term AD compared to those who had spontaneously regressed, had newly developed AD or did not have AD [22]. Anan and Yamamoto reported that 287 out of 1,072 6-year-old children in Nagasaki had a present (91) or past history (196) of AD in 1995, that is, 68.3% (196/287) of AD children experienced spontaneous regression by age 6 [25]. They also followed up on 50 AD children of 6 years old and found that 30 children had spontaneously regressed within the subsequent 6 years [25]. In Hiroshima, mean prevalence of AD children of 6 years old from 1992 to 1997 was 13.6% (male: 13.6%, female: 13.7%; total number 1,327) [26]. Among 121 children of 6 years old with AD, 61 were cured and 22 had improved 5 years later. Among 464 non-AD pupils of 6 years old, 6 (1.3%) had AD 5 years later [26]. Williams and Strachan analyzed the age of onset and clearance rates for examined and/or reported eczema in 6,877 children born during the period 3-9 March 1958 for whom linked data was available at birth and at the ages of 7, 11, 16 and 23 years. Of the 870 cases with examined or reported eczema by the age of 16 years, 66% had experienced onset by the age of 7 years. Of the 571 children with reported or examined eczema by the age of 7 years, the proportion of children who were clear in terms of examined or reported eczema in the last year at ages 11 and 16 years was 65% and 74%, respectively. These 'apparent' or short-term clearance rates fell to 53% and 65%, respectively, after allowing for subsequent recurrences in adolescence and early adulthood [27]. Uehara et al. [28] examined the regression rate of 266 AD cases (older than 2 years of age at the first visit in 1953 to 1961) in 1966 (5 to 13 years later) by questionnaire. They reported that AD was cured in 76 cases (29%). In the 190 uncured cases, 40 cases experienced a short regression of more than a year's duration. Of these 40 cases, 36 (90%) reported that their transient regression appeared within 15 years after the onset of AD, and 29 cases (79%) reported that their transient regression did not last more than 5 years [28]. Another questionnaire study revealed that either transient or complete remission occurred in 33.3% of 794 AD patients (10-20 years old) [29]. In a mail-in questionnaire study, 220 AD patients (mean age: 21.3 ± 11.8) were monitored every 3 months by for 3 years from 2006 to 2009. Thirty-six (16.4%) patients reported having at least a year's remission. Four cases developed atopic cataract (12, 13, 54 and 59 years old) during this period and none of the four had experienced any remission. Patients older than 30 years had a significantly lower remission rate compared to those younger than 30 years [30].

The regression of adult-type AD tends to occur more slowly. Our 95 cases of adult AD (mean age 23.9 ± 11.5 in 1991-1992, male: 45, female: 50) reported the following in 1996: AD was cured (10.5%), much improved (32.6%), slightly improved (34.7%), and unchanged or worse (22.1%). Eleven patients reported that the onset of AD was as late as 18 years or older. Association with other allergic disease significantly lowered the regression/improvement rate compared to the pure AD group [31]. The severity of AD also increased according to age. Yamamoto demonstrated that the percentage of mild cases decreased gradually with age (84.3% at 1.5 years old, 85% at 3 years old, 75.9% at 6 years old, 71.6% at 12 years old and 72.7% at 18 years old), while the percentage of moderate cases increased inversely (12.4% at 1.5 years old, 11.8% at 3 years old, 22.4% at 6 years old, 26.3% at 12 years old and 21.9% at 18 years old) [20]. This phenomenon can be caused by numerous aggravating factors including hormonal imbalance in adolescence, increased physical and schoolwork stress, and emotional stress related to social and family issues. Decreased compliance with treatment regimens may also contribute to the deterioration of AD.

Although topical steroids, emollients and oral antihistamines are used as the first-line therapy for AD, long-term application, even with intermittent use, induces local and unavoidable adverse effects such as skin atrophy and telangiectasia in a substantial percentage of patients. These adverse effects and the emotional fear of long-term use of topical steroids have induced a topical steroid phobia in patients throughout the world [32].

Before the topical tacrolimus was commercially available in Japan, we collected clinical data on 1,271 AD patients who had been followed for at least 6 months in outpatient clinics [33]. The check sheet for each patient included the following items: age; gender; duration of AD; global severity before treatment; global severity after 6 months of conventional topical steroid therapy; evaluation of clinical improvement; total dose of each rank of topical steroids per 6 months' therapy on the face, scalp, trunk and extremities; association with herpes simplex infection and/or Kaposi's varicelliform eruption; association with molluscum contagiosum; and adverse effects of topical steroids (telangiectasia on cheeks, skin atrophy of antecubital/popliteal fossae, acne and folliculitis, hypertrichosis, bacterial infection, dermatomycosis, rosacea-like dermatitis, contact dermatitis caused by topical steroids, and steroid-induced striae atrophicae). Global clinical severity was classified as "very severe", "severe", "moderate" and "mild". The ranking of topical steroids was "strongest", "very strong", "strong", "mild" and "weak" in Japan.

The 1,271 patients with AD were divided into 3 groups according to age: 210 infantile (0-2 year old) cases, 546 childhood (≥2 and <13 years old) cases, and 515 adolescent and adult (≥13 years old) cases. All of the patients were treated with topical steroids and moisturizing emollients. The clinical severity of AD in the majority of patients improved or was unchanged after 6 months of conventional therapy ("controlled" group). However, 7% of infantile AD, 10% of childhood AD and 19% of adolescent and adult AD patients remained in a very severe or severe state or experienced exacerbation ("uncontrolled" group) (Table 3) [33]. This data suggested that the incidence of very severe and severe AD was significantly higher in the adolescent/adult AD group than in the infantile and childhood groups. Concordantly, Brunsting pointed out in 1936 that the recurrent lesions of adolescent and adult AD were resistant to treatment by local measures [34]. These uncontrolled patients were considered as "intractable" and they received much attention as a social problem in Japan.

The total doses of topical steroids used during the 6-month treatment period are listed in Table 4 as median, 75 percentile and 90 percentile doses. During the 6 months, 90% of AD patients used less than 89.5 g, 135 g and 304 g of topical steroids on the entire body in the infantile, childhood, and adolescent/adult groups, respectively. The 90 percentile doses applied on the face during the 6 months were 10 g, 15 g and 35 g in the infantile, childhood and adolescent/adult AD groups, respectively. The amount of topical steroids applied in this survey was much less than that reported by Wilson et al. and Munro et al. [35, 36]. Association with herpes simplex virus infection and/or Kaposi's varicelliform eruption was found in 2.4% of infantile AD patients, 2.5% of childhood AD patients and 3.5% of adolescent and adult AD patients during the 6-month treatment period. Association with molluscum contagiosum was detected in 7% of infantile AD patients, 9% of childhood AD patients, and 0.2% of adolescent and adult AD patients. The cumulative incidence of adverse effects was assessed (Table 5) and as expected, it was much higher in the adolescent and adult AD patients than in the infantile AD patients. Telangiectasia on the cheeks and skin atrophy of antecubital/popliteal fossae were frequently observed as the predilection sites of AD (face and flexure areas). There was a small but appreciable percentage of patients with adverse effects such as local skin atrophy and telangiectasia [33]. The incidence of these adverse effects might be predicted by age, sex, and strength and quantity of topical steroids. In addition, these adverse effects were reversible [37].

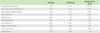

We next examined the topical steroid doses used in the "controlled" and "uncontrolled" groups (Table 6) [33]. The total usage of topical steroids was unexpectedly higher in the "uncontrolled" group than in the "controlled" group. The statistical difference became more obvious in the adolescent/adult group than in the childhood group (Table 3). Topical steroids are useful for treating AD, but there appears to be a subgroup of patients who remain severe despite increasing applications of topical steroids. Nevertheless, all of the patients in the "uncontrolled" group may not have been "uncontrollable", because the total application dose per 6 months in 50% of the "uncontrolled" patients was very small (Table 6, undertreatment state). Undertreatment may cause or enhance the development of the "uncontrolled" group. The most popular tube size of topical steroids is 5 g in Japan, which is much smaller than European and American tubes (Fig. 3). This may, at least in part, contribute to topical steroid undertreatment in Japan. Suitable amounts of topical steroid application, such as the fingertip-unit dose [38], may markedly decrease the percentage of the "uncontrolled" group. Various social, economic and ecological factors together with the medical insurance system may affect "steroid phobia"-related undertreatment.

Atopic cataract is another important issue that may be misunderstood by AD patients. Brunsting first described atopic cataract in detail in 1936 [34]. He demonstrated the frequent association of juvenile cataract with AD in 10 out of 101 AD patients (mean age: 22 years old) [34]. He then performed an ophthalmological check in 1,158 AD patients from 1940 to 1953, and found typical atopic cataract in 136 patients (11.7%) including 79 cases of visual disturbance [39]. He also pointed out that the rapid progression of atopic cataract in adolescent- and adult-type AD was usually associated with the exacerbation of skin eruption [34, 39]. The incidence of atopic cataracts in Japanese AD patients is also around 10-15% in the literature. Importantly, steroids were not available as medication until 1949 to 1952 [40]. These facts emphasize that atopic cataract is a distinct clinical sign of AD, and is likely induced by repeated scratching/rubbing/patting of facial and periocular lesions and is not directly related to steroids [41-44]. Retinal detachment and subsequent blindness are also serious ophthalmological complications [42].

AD is a very common skin disease in dermatology clinics in Japan. The English version of the guidelines for management and severity of AD by the Japanese Dermatological Association have been published in literature [45-47], the principals of which are identical to those of other academic societies. AD affects patients across several generations with different disease activity. Genetic, environmental and emotional factors are variably involved in the onset and clinical course of AD. It is also a challenging task to fight against topical steroid phobia in daily clinics. Therefore, the Japanese guideline for AD includes many practical instructions for the patients [45]. Education, understanding and cooperation of patients and their guardians are a key issue for the successful treatment of AD.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Age distribution of outpatients with atopic dermatitis at the Branch Hospital, University of Tokyo. |

| Fig. 2Age distribution of atopic dermatitis in dermatology clinics. Report from the Japanese Dermatological Association (n = 6,733). |

| Fig. 3In Japan, 5-g tubes are typically used in daily clinics. Larger tubes (100 g or 50 g) are more commonly used in Europe and the USA. |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan.

References

1. Williams HC. Is the prevalence of atopic dermatitis increasing? Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992. 17:385–391.

2. Williams HC, Robertson C, Stewart A. Worldwide variations in the prevalence of symptoms of atopic eczema in the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999. 103:125–138.

3. Takeuchi M, Ueda H. Increase of adult atopic dermatitis (AD) in recent Japan. Environ Dermatol. 2000. 7:133–136.

4. Sugiura H, Umemoto N, Deguchi H, Murata Y, Tanaka K, Sawai T, Omoto M, Uchiyama M, Kiriyama T, Uehara M. Prevalence of childhood and adolescent atopic dermatitis in a Japanese population: comparison with the disease frequency examined 20 years ago. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998. 78:293–294.

5. Sulzberger MB. Historical notes on atopic dermatitis: Its names and nature. Semin Dermatol. 1983. 2:1–4.

7. Wise F. The neurodermatoses and pseudo-lichens: a consideration of their nosological and clinical features. J Cutan Dis. 1919. 37:590–620.

8. Low RC. The eczema-asthma-prurigo-complex. Br J Dermatol. 1928. 40:389–406.

9. Coca AF, Cooke RA. On the classification of the phenomena of hypersensitiveness. J Immunol. 1923. 8:163–182.

11. Sulzberger MB, Spain WC, Sammis F, Shahon HI. Studies in hypersensitiveness in certain dermatoses. I. Neurodermatitis (disseminated type). J Allergy. 1932. 3:423–437.

13. Sulzberger MB, Rostenberg A Jr. Practical procedures in the investigation of certain allergic dermatoses. J Allergy. 1935. 6:448–459.

14. Schultz Larsen F. Atopic dermatitis: a genetic-epidemiologic study in a population-based twin sample. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993. 28:719–723.

16. Furue M. Tamaki K, Furue M, Nakagawa H, editors. History of atopic dermatitis. Atopic dermatitis and topical steroid therapy. 1998. Shinjuku: Chugai-Igakusha;1–19.

17. Furue M, Yamazaki S, Jimbow K, Tsuchida T, Amagai M, Tanaka T, Matsunaga K, Muto M, Morita E, Akiyama M, Soma Y, Terui T, Manabe M. Prevalence of dermatological disorders in Japan: a nationwide, cross-sectional, seasonal, multicenter, hospital-based study. J Dermatol. 2011. 38:310–320.

18. Yura A, Shimizu T. Trends in the prevalence of atopic dermatitis in school children: longitudinal study in Osaka Prefecture, Japan, from 1985 to 1997. Br J Dermatol. 2001. 145:966–973.

19. Yura A, Kouda K, Iki M, Shimizu T. Trends of allergic symptoms in school children: large-scale long-term consecutive cross-sectional studies in Osaka Prefecture, Japan. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2011.01159.x. [Epub ahead of print].

20. Yamamoto S. Prevalence and exacerbation factors of atopic dermatitis. Skin Allergy Frontier. 2003. 1:85–90.

21. Hamada M, Furusyo N, Urabe K, Morita K, Nakahara T, Kinukawa N, Nose Y, Hayashi J, Furue M. Prevalence of atopic dermatitis and serum IgE values in nursery school children in Ishigaki Island, Okinawa, Japan. J Dermatol. 2005. 32:248–255.

22. Fukiwake N, Furusyo N, Kubo N, Takeoka H, Toyoda K, Morita K, Shibata S, Nakahara T, Kido M, Hayashida S, Moroi Y, Urabe K, Hayashi J, Furue M. Incidence of atopic dermatitis in nursery school children - a follow-up study from 2001 to 2004, Kyushu University Ishigaki Atopic Dermatitis Study (KIDS). Eur J Dermatol. 2006. 16:416–419.

23. Kawaguchi H, Takeuchi M, Tanaka Y, Ishii N, Ikezawa Z. Atopic dermatitis at 18-months physical examination. Arerugi. 2000. 49:653–657.

24. Illi S, von Mutius E, Lau S, Nickel R, Grüber C, Niggemann B, Wahn U. Multicenter Allergy Study Group. The natural course of atopic dermatitis from birth to age 7 years and the association with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004. 113:925–931.

25. Anan S, Yamamoto N. Spontaneous regression of atopic dermatitis. Hifu. 1996. 38:suppl 18. 13–15. (in Japanese).

26. Okano S, Takahashi H, Yano T, Yamura M, Niimi N, Tanaka K, Iguchi H, Nakayama S, Horie M, Kuwahara M, Oda K, Hashimoto N, Doi T, Okino H, Imoo K, Doki M. Prevalence of childhood atopic dermatitis in first-year pupils of elementary school and its follow-up: Asa district in Hiroshima. Nihon Ishikai Zasshi. 2006. 135:97–103. (in Japanese).

27. Williams HC, Strachan DP. The natural history of childhood eczema: observations from the British 1958 birth cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 1998. 139:834–839.

28. Uehara M, Otaka T, Ogawa Y, Ofuji k. Clinical course of atopic dermatitis. Hifuka-Kiyo. 1970. 65:1–6.

29. Furue M, Kawashima M, Furukawa F, Iiduka H, Ito M, Shiohara T, Shimada S, Takigawa M, Takehara K, Miyaji Y, Katayama I, Iwatsuki K, Hashimoto K. Questionnaire study for chronological change in atopic dermatitis. Rinshohifuka. 2007. 61:286–295.

30. Furue M, Kawashima M, Furukawa F, Iiduka H, Ito M, Shiohara T, Shimada S, Takigawa M, Takehara K, Miyaji Y, Katayama I, Iwatsuki K, Hashimoto K. A prospective questionnaire study for atopic dermatitis. Rinshohifuka. 2011. 65:83–92.

31. Furue M, Hayashida S, Uchi H. Natural history of atopic dermatitis. Rinshomeneki-Arerugika. 2009. 52:320–325.

32. Charman CR, Morris AD, Williams HC. Topical corticosteroid phobia in patients with atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2000. 142:931–936.

33. Furue M, Terao H, Rikihisa W, Urabe K, Kinukawa N, Nose Y, Koga T. Clinical dose and adverse effects of topical steroids in daily management of atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2003. 148:128–133.

34. Brunsting LA. Atopic dermatitis (disseminated neurodermatitis) of young adults. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1936. 34:935–957.

35. Wilson L, Williams DI, Marsh SD. Plasma corticosteroid levels in outpatients treated with topical steroids. Br J Dermatol. 1973. 88:373–380.

36. Munro DD, Clift DC. Pituitary-adrenal function after prolonged use of topical corticosteroids. Br J Dermatol. 1973. 88:381–385.

37. Furue M, Terao H, Moroi Y, Koga T, Kubota Y, Nakayama J, Furukawa F, Tanaka Y, Katayama I, Kinukawa N, Nose Y, Urabe K. Dosage and adverse effects of topical tacrolimus and steroids in daily management of atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol. 2004. 31:277–283.

38. Long CC, Finlay AY. The finger-tip unit--a new practical measure. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1991. 16:444–447.

39. Brunsting LA, Reed WB, Bair HL. Occurrence of cataracts and keratoconus with atopic dermatitis. AMA Arch Derm. 1955. 72:237–241.

40. Goldman L, Thompson RG, Trice ER. Cortisone acetate in skin disease; local effect in the skin from topical application and local injection. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1952. 65:177–186.

41. Haeck IM, Rouwen TJ, Timmer-de Mik L, de Bruin-Weller MS, Bruijnzeel-Koomen CA. Topical corticosteroids in atopic dermatitis and the risk of glaucoma and cataracts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011. 64:275–281.

42. Taniguchi H, Ohki O, Yokozeki H, Katayama I, Tanaka A, Kiyosawa M, Nishioka K. Cataract and retinal detachment in patients with severe atopic dermatitis who were withdrawn from the use of topical corticosteroid. J Dermatol. 1999. 26:658–665.

43. Nagaki Y, Hayasaka S, Kadoi C. Cataract progression in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1999. 25:96–99.

44. Matsuo T, Saito H, Matsuo N. Cataract and aqueous flare levels in patients with atopic dermatitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997. 124:36–39.

45. Saeki H, Furue M, Furukawa F, Hide M, Ohtsuki M, Katayama I, Sasaki R, Suto H, Takehara K. Committee for Guidelines for the Management of Atopic Dermatitis of Japanese Dermatological Association. Guidelines for management of atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol. 2009. 36:563–577.

46. Yoshida H, Aoki T, Furue M, Tagami H, Kaneko F, Ohtsuka F, Nishioka K, Toda K, Mizoguchi M, Nakayama H, Ikezawa Z, Takigawa M, Arata J, Yamamoto S, Tanaka Y, Ishigaki M, Kusunoki T, Yoshikawa K. English version of the interim report published in 1998 by the members of the Advisory Committee on Atopic Dermatitis Severity Classification Criteria of the Japanese Dermatological Association. J Dermatol. 2011. 38:625–631.

47. Aoki T, Yoshida H, Furue M, Tagami H, Kaneko F, Ohtsuka F, Nishioka K, Toda K, Mizoguchi M, Ichihashi M, Ueki H, Nakayama H, Ikezawa Z, Takigawa M, Arata J, Koro O, Yamamoto S, Tanaka Y, Ishigaki M, Kusunoki T, Yoshikawa K. English version of the concluding report published in 2001 by the Advisory Committee on Atopic Dermatitis Severity Classification Criteria of the Japanese Dermatological Association. J Dermatol. 2011. 38:632–644.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download