Abstract

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is the most common chronic inflammatory skin disorder in children, with a worldwide cumulative prevalence in children of 8-20%. The number of AD patients is beyond the level that can be dealt with at clinics and it is time to make an effort to reduce the number of AD patients in the community. Thus, caregivers and all persons involved with AD management, including health care providers, educators, technologists and medical policy makers, should understand the development and the management of AD. Although a number of guidelines such as Practical Allergy (PRACTALL) report have been developed and used, community understanding of these is low. This is probably because there are still remarkable differences in management practices between specialists and between countries and most of the reported guidelines have been prepared for physicians. From the viewpoint of providing a basis for a multidisciplinary team approach, easily comprehensible guidelines for organizing treatment of AD, i.e. an Atopic Dermatitis Organizer (ADO), are required. guidelines should be simple and well organized. We suggest an easy approach with a new classification of AD symptoms into early and/or progressive lesions in acute and/or chronic symptoms. The contents of this ADO guideline basically consist of 3 steps approaches: conservative management, topical anti-inflammatory therapy, and systemic anti-inflammatory therapy.

While atopic dermatitis (AD) has been classified into two types depending on its immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated mechanism, it is generally accepted as one of the major allergic diseases, particularly in children, because it shows many of the characteristics of allergic diseases such as bronchial asthma (BA) and allergic rhinitis (AR). These characteristics include a strong familial predisposition, evidence of an IgE-mediated immune response, sensitivity to allergens and environmental triggers, and like BA and AR, a rapid increase in prevalence since the 1980s. However, unlike other allergic diseases, it is commonly observed in infants and young children and shows a clear tendency to disappear or improve with increasing age. AD also has characteristic symptoms of rough and dry skin rather than the edematous lesions usually found in other allergic diseases. These similarities and differences are very helpful in providing a direction for research and in developing effective management.

This article reviews the epidemiologic characteristics and the natural course of AD and proposes a new approach for the management of AD to reduce the number of patients in the community.

As the pathogenesis of AD remains unknown, it has been named differently in different regions. Until the 1970s in Korea, it was considered a temporary skin phenomenon observed during early infancy and was called "infantile eczema" or "fetal fever". The European revised nomenclature committee has proposed the term atopic eczema/dermatitis syndrome instead of atopic eczema [1].

The definition of the disease, like its name, also varies. Based on a comprehensive review of the literature, we suggest that the best definition of AD is a chronic relapsing inflammatory skin disease found mainly in infants and young children with intensely itchy and dry skin.

It is clear that the prevalence of allergic diseases such as AD, BA and AR has increased all over the world during the last 30 years [2, 3]. Although the prevalence differs by age, region and survey method, the cumulative prevalence of AD in children is 8-20% [4] and, as demonstrated by an International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) continues to increase. Korean ISAAC data from elementary school children aged 6-11 years, reported every five years since 1995, have also revealed that the cumulative prevalence of AD has increased continuously from 19.7% in 1995 to 29.2% in 2010. However, this differed markedly from the point prevalence: a survey in 2009 using the ISAAC questionnaire showed 13.1% prevalence of symptoms in the previous 12 months and 8.2% prevalence identified by direct physical examination by pediatric allergist [5].

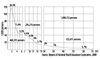

Another epidemiologic characteristic of AD is that it is observed primarily during infancy. Kay et al. [6] reported that 45% of all cases of AD begin within the first six months after birth, 60% during the first year and 85% before five years of age. This tendency is also shown in the data collected in Korea. According to the data from the Korean National Health Insurance Corporation in 2008 (Fig. 1), 1.08 million patients (2.24% of the total population) were registered as having AD. These patients were diagnosed by clinicians: pediatricians, dermatologists, internists, family physicians and traditional medicine practitioners. Around 118,000 infants aged one year (26.5% of the population of this age group) were diagnosed with AD. The rate of diagnosis dramatically reduced with increasing age: 11.6%, 9.2%, 4.6%, 2.0% and 1% in those aged 3, 5, 10, 20 and 30 years, respectively. Among persons aged over 40, the rate was less than 0.7%. These data suggest that AD principally develops in infancy.

In Korea, there is an old saying that "infantile eczema disappears when children stand alone or start to talk". In the early 1990s, the textbook introduced AD as a disease with a very high possibility of disappearing at 2-3 years of age [7].

Illi et al. [8] reported a prospective birth cohort study performed with 1,314 subjects from birth to seven years of age. Of the patients with AD that occurred before two years of age, 43.2%, 38.3% and 18.7% showed complete remission, intermittent symptoms or continuous symptoms, respectively, at three years of age [8].

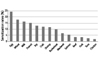

The cumulative prevalence and the point prevalence of AD among elementary school children in Seoul, Korea, have been reported every five years (Fig. 2) [9]. Both measures of prevalence increased continuously but because the one-year point prevalence was about half the cumulative prevalence, it was assumed that 50% of AD resolved in elementary school children.

Many genetic and epidemiologic studies have been performed [10-12], and have concluded that AD is caused by multiple environmental triggers in susceptible individuals. The Practical Allergy (PRACTALL) consensus report also extensively reviewed the development of AD [13], but there are still many points that are difficult to explain. Why does AD occur principally during infancy and why do its frequency and severity decrease with increasing age? Why has its prevalence increased sharply since the 1980s along with that of BA and AR and why does AD in infancy frequently progress to BA and AR? Why are there few symptoms of edema which are frequently found in BA, AR and urticaria?

Overall, the development of AD is considered to be multifactorial. In short, the mechanisms for the development of AD involve complex interactions between susceptibility genes, immaturity and/or abnormality in barrier function and environmental factors (Fig. 3).

It is well known that genetic factors are involved in all diseases and many genetic factors associated with allergic disease have been reported. In particular, evidence of a high correlation between AD and family history has been found. A cohort study by the authors reported such a finding [14]. When both parents had a family history and showed sensitization to allergens in a skin prick test, the cumulative prevalence of AD up to one year of age was 41.7%; when only the mother showed sensitization the rate was 30.7%. However, the rates of AD in children with only a sensitized father and with nonsensitized parents were relatively low, recorded as 22.2% and 14.7%, respectively. These data suggest that parental atopy, particularly maternal atopy, is significantly associated with AD in infants.

It has been demonstrated that the prevalence of allergic diseases increases in a community with a high socioeconomic level. Because the prevalence of AD was inversely proportional to the prevalence of bacterial infections such as tuberculosis and its incidence rate was relatively low in larger families or rural areas, the "hygiene hypothesis" was conceived. This hypothesis proposes that exposure to bacteria in early infancy plays a major role in setting the direction of immune responses, including whether a T helper (Th) 1 (proinflammatory) or Th2 (proallergic) type of reaction is dominant [15]. Although the hypothesis has recently been questioned with regard to AD [16, 17], it is a reasonable concept to explain the rapid increase of allergic diseases during the past a few decades.

Environmental factors resulting from industrialization have been studied as possible reasons why the incidence of BA, AR and AD has skyrocketed since the 1980s. Air pollution generated by cars, energy production and factories, air-conditioning and heating, indoor environmental changes, and dietary changes have been suggested as factors in the development and aggravation of AD [16-18].

Some studies showed that exposure to volatile organic compounds (VOCs) found in indoor environments can damage the epidermal barrier and enhance adverse reactions to house dust mite (HDM) [21, 22]. Air pollutants, such as hydrogen sulfide, nitrogen dioxide and formaldehyde, may increase the prevalence and severity of AD [19, 23]. The authors' current survey of the residential environment of severe AD patients also revealed that particulate matter (PM10), formaldehyde, fungi and bacteria levels were high, implying that these could be factors aggravating AD.

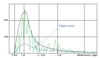

Food has also been frequently raised as a factor. Based on the literature from the past 10 years, the prevalence of food allergy in infants with AD was reported to range from 33% to 63% [24]. According to the authors' study of food-specific IgE in AD patients, egg-white-specific IgE was detected in 24.3% of patients followed by wheat-, milk-, peanut- and soy-specific IgE in order of decreasing frequency (Fig. 4). However, it should be considered that the causative foods of AD differ by country, region and culture. Because most of causative foods are essential for the growth of infants and children, food restrictions should be imposed with care.

The skin environment of the lesions plays a key role in the incidence of AD. The skin of patients with AD is mostly colonized by Staphylococcus aureus, a toxin-producing organism [25]. Toxins and superantigens secreted by S. aureus activate high numbers of T cells and other immune cells, resulting in an exaggerated inflammatory response [13, 25]. The skin of AD patients has been found to be deficient in antimicrobial peptides, one of the components of the innate response essential for host defense against bacteria, fungi and viruses [26, 27]. This abnormality of innate immunity may explain the increased susceptibility to various skin infections of patients with AD. In addition, skin infection is a factor aggravating AD and hindering its treatment.

It has been observed that an increased ceramide level and decreased endogenous proteolytic enzymes in skin cause elevated transepidermal water loss, which provokes a vicious cycle of lesions and abnormal skin barrier function. Studies of a mutation of filaggrin, a major protein essential to skin barrier formation, have recently been reported [28]. A study demonstrating a correlation between the mutation and BA was also reported [29]. It was suggested that elevated production of the stratum corneum chymotryptic enzyme protease led to the breakdown of the skin barrier [29]. Soaps and detergents can increase skin pH and strengthen the activity of proteases from dust mites or S. aureus, thus contributing to epithelial damage.

Although the prevalence of AD has increased greatly compared with the past, its tendency to occur most frequently among infants aged one year or less and to reduce with increasing age has been maintained. Therefore, while the incidence of AD is greatly affected by changes in the environment, overall physical immaturity is expected to be an important factor influencing this incidence.

In summary, immaturity of skin barrier function, mucosal immunity, systemic immunity and digestive enzymes are considered to be factors that influence the development of AD symptoms in infancy.

Many studies of AD have been conducted over the last 30 years, but it is difficult to suggest treatment guidelines because there are many unexplained factors and still remarkable differences in management practices. The lack of a therapy considered as routine by all practitioners is the major problem in overcoming the disinformation that abounds in the lay press and among health professionals.

This ADO guideline was written with the concept of AD as 1) a multifactorial inflammatory disease, 2) one of the most common chronic childhood diseases predominantly found in infants and young children, 3) a disease that tends to wax and wane over time, and 4) a disease that disappears with increasing age and/or progresses to BA or AR.

Corticosteroid (CS) treatment is essential for the early-intervention management of inflammation, but ways to improve its safety and minimize adverse reactions have been introduced to relieve the anxiety of patients and their caregivers. Causes and treatments of AD vary between individuals, the individualization of management is also considered.

Because the number of patients is too great to be handled by doctor's offices only, a role of the general public, including patients, guardians, educators, press and policy makers, is necessary. This guideline was devised to communicate in a simple way with these groups. What should be considered is that patients and their guardians do not properly understand the chronic nature of AD and its tendency for frequent relapsing and remitting, and may have various levels of awareness of the severity of the disease. This can mean that their distrust of and anxiety over treatment reduces their compliance. Thus, the guideline includes an explanatory section to correct any mistaken beliefs of the general public, patients and their families and to satisfy their expectations of a therapeutic effect.

Methods to diagnose AD, such as Hanifin and Rajka's criteria [30], and those to evaluate the severity of symptoms, such as SCORAD [31], have been reported and have been widely used for research and education. However, "early diagnosis and early intervention", which is a mainstay of the management of allergic diseases, is more important for AD management than determining whether symptoms meet the diagnostic criteria or how severe the symptoms are. Experienced physicians can easily diagnose AD because the characteristic symptoms and lesions of AD are unique and are common in infants and young children. If the family has a history of allergic diseases, AD can be diagnosed from the early lesions. However, differential diagnoses such as seborrheic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, nummular eczema, psoriasis and immunodeficiency should be considered.

Both symptoms from acute and chronic lesions defined by skin desquamation and thickening can coexist in AD. Depending on progression of lesions, there are characteristic findings: early and progressive lesions.

This classification is useful to determine when early intervention will be performed and what kind of therapeutic level should be given. Thus, both acute and chronic lesions have early and progressive stages, which can be classified as follows:

• Acute symptom:

- Early lesion: scaly, erythematous patches with a poorly defined border

- Progressive lesion: weeping, excoriation, crusting, and infections

• Chronic symptom:

- Early lesion: thicker, paler, scaly plaques

- Progressive lesion: thickened and hyperlinear skin with erythematous, scaling papules and patches

Although it is not easy to distinguish between acute and chronic symptoms, one is differentiated from the other by the degree of skin thickness observed by inspection and palpation. For acute symptom, red and palpable rough skin is considered as an early lesion and the association of weeping with more severe skin eruptions is regarded as a progressive lesion. For chronic symptom, the skin is thicker than in acute symptoms. Early and progressive lesions of chronic symptoms are divided by the degree of thickness and wrinkles. Chronic symptoms frequently combine with acute symptoms.

Itching is an essential symptom for the diagnosis of AD. The distribution of skin lesions is very characteristic. In infants, the face, neck, trunk and lateral surface of the extremities are commonly affected. As children grow older, the lesions move to or expand to the cubital and popliteal fossae, ear lobes, wrists and ankles where the skin is folded. As these symptoms recur, in a typical chronic lesion the skin becomes thickened and wrinkled. In the chronic stage, complications including infections are more frequent and it can produce very severe acute symptoms.

Because AD is an inflammatory disease, using anti-inflammatory drugs is the cornerstone of treatment. In particular, CSs have been widely used as one of the strongest and most effective types of anti-inflammatory drugs. However, they can cause adverse reactions such as inhibition of growth of children and a rebound phenomenon, which lead to anxiety for patients and their caregivers.

This ADO guideline refers to the treatment steps of PRACTALL, which are based on CS preparation. While PRACTALL classifies the treatment stages by severity of disease [13], this ADO guideline classifies them by acute and chronic symptoms and by early and progressive lesions.

The basic framework of the ADO guideline consists of three steps (Fig. 5). Step 1 management is basic management for all cases of AD. It consists of skin care, dietary management, indoor environmental control and psychological support. Just carrying out this step faithfully can decrease the deterioration of symptoms and the use of CS drugs. Step 2 therapy is an add-on therapy to treat skin inflammation and itching of acute lesions that do not improve with step 1 management. Topical CS (TCS) therapy is the major therapeutic agent in step 2 therapy, and topical calcineurin inhibitor (TCI) can also be used for children over two years of age. Antihistamines for itching and antibiotics for skin infection are also included. Step 3 therapy is systemic administration of CS in cases not improved by steps 1 and 2 therapy. Immunosuppressive treatments such as cyclosporin A, azathioprine, immunotherapy, intravenous immunoglobulin, ultraviolet (UV) light therapy and unverified treatments such as herbal medicines may also be included in step 3 therapy.

This step is the basic and essential management for all stages of AD. It consists of proper skin care, dietary management, and indoor environmental control without medication. In addition, it includes psychological support and education of the parents. If conducted thoroughly, it is very effective for treating the early lesions of acute and chronic symptom and is the best way to reduce the use of medicines and the exacerbation of acute symptoms and to induce resolution of the disease at an early age.

Basic skin care is essential for AD management. AD patients have characteristically dry skin following the loss of water in the skin because of skin damage. Various exacerbating factors trigger pruritic skin inflammation, which often leads to a vicious cycle of scratching followed by further itching. This damaged skin is vulnerable to infections with bacteria, fungi, viruses and scabies. The skin of AD patients is mostly colonized by S. aureus, a toxin-producing organism. Therefore, proper skin care consists of skin hygiene, moisturizing and avoidance of irritants.

Regular showers and tub bathing: For skin hygiene and hydration, regular showers and tub bathing are essential. Although soap can be used for skin hygiene, it can produce skin damage. For decreasing skin damage, neutral or weakly acidic pH soaps have been recommended. However, it should be rinsed off thoroughly with clean water after bathing.

Moisturizers: Emollient should be applied regularly. The roles of ideal moisturizers are as follows: 1) to improve skin dryness [32], 2) to maximize treatment effects of TCS [33], 3) to decrease the amount of TCS required [34], and 4) to reduce chances of infection by recovering disrupted skin barrier [35].

Avoidance of irritants: Irritation is also an aggravating factor for AD. Patients with AD are recommended not to wear too tight or loose clothing, and not to use fabrics producing static electricity [36].

Because AD frequently occurs at ages involving a growth spurt, nutrients for growth must be supplied. Therefore, dietary restriction should be applied carefully, and if a food must be avoided, appropriate diets that will not hamper normal growth should be prepared by choosing a substitute food. As the possibility for food to be a trigger of AD is higher at younger ages, food management at this age is critical for AD management. Dietary management is classified into food avoidance and preparation of a diet for proper nutrient supply.

Food avoidance: Because the results of a laboratory test are not always consistent with symptoms, food cannot be restricted based only on the result of a laboratory test. Food diary and challenge test are necessary for the confirmations. When food challenge is conducted, careful attention should be paid to the possibility of anaphylaxis in patients with urticaria or angioedema rather than AD.

For the prevention of AD, breast feeding is commonly recommended. However, it should be considered that the maternal diet can produce symptoms of AD. Probiotics are sometimes recommended in high-risk infants [37].

Nutrient management: When a food that is confirmed to be associated with AD is avoided, food substitution should be provided. The cooking method is also considered. For example, raw rice shows an allergenic band in immunoblotting but the band disappears after boiling [38]. Cooking methods such as roasting were reported to enhance allergenicity [39].

Studies in Korea and other countries have reported that residential environmental pollution is a factor in the development of symptoms of AD [2, 40-44]. Our clinical study on the therapeutic effect of a low-pollutant (PM10, formaldehyde, bacterial and mold suspension) ward also revealed that improvement of the environment had a positive effect. The duration of treatment was reduced and the pollutant levels were measured to be higher at the patient's home than in the wards. Children spend over 20 h a day in indoor environments including childcare facilities, daycare centers, kindergartens, schools and private educational institutions, so reducing pollution in the indoor environment is important for AD management.

Ventilation: Ventilation is the first step to reduce indoor pollution. Pollutants from new furniture, furnishing materials including wallpaper, air-conditioning and heating equipment and cooking utensils should be decreased by ventilation. New interiors or new furniture need more frequent ventilation. An air cleaner is also helpful but a habit of frequent ventilation is more effective and reliable.

Cleaning: Fungi and bacteria can be factors in worsening symptoms of AD and can provoke more severe symptoms in skin lesions with infection. Cleaning is the best way to decrease fungi and bacteria in the indoor environment [45, 46].

Adequate humidity: Maintaining adequate humidity is effective in reducing the deterioration of lesions by preventing dry skin. However, excessive humidity can promote the propagation of HDM, fungi and bacteria, so it is appropriate to maintain around 50% humidity.

The most common problem in severely affected AD children is exhaustion from not sleeping well, leading to poor concentration at school [47]. Dietary restriction and anxiety can negatively affect the development of confidence, autonomy and personal initiative. In most cases of moderate to severe AD, counseling is required to help overcome the emotional burdens associated with the disease itself and the fears that most parents have about treatment, such as steroid phobia.

Step 2 therapy should be added for acute symptoms of AD if the skin lesion is not improved by step 1 management. The targets of step 2 therapy are to break out of the vicious cycle of disease and to treat skin inflammation.

Antihistamines are widely used for the management of pruritus. Antihistamines are generally divided into six groups. Depending on their action time and sedative properties, each group is classified into first- and second-generation drugs. When tachyphylaxis occurs, an antihistamine from another group can be used. Sedating first-generation antihistamines are still more useful in AD than the nonsedating antihistamines [48], but their use in children is often reserved for nighttime dosing to minimize drowsiness and lack of concentration during the daytime [49].

Disruption of the skin barrier and a deficiency in the expression of antimicrobial peptides may account for the susceptibility of AD patients to various skin infections by bacteria, fungi and viruses [26, 27, 50-52]. Heavy colonization of AD patients' skin with S. aureus is well documented [24].

Skin infection is a major factor in aggravating symptoms of AD. Suspected skin infection is hard to differentiate from progressive lesions in many cases. Generally, an infected lesion tends to have a well-defined margin compared with early lesions that have poorly defined margins.

For bacterial infection, systemic antibiotics are preferred rather than topical agents. Generally, a first- or second-generation cephalosporin for 7-10 days is recommended. In case of infections with viruses, fungi or scabies, it is better to use individualized therapy. If there is no therapeutic ef fect, skin culture for microorganisms should be performed.

For early and progressive lesions of acute symptom not improving with step 1 management, topical anti-inflammatory therapy should be applied. Although TCS is most widely used, many patients and their guardians are reluctant to use it because of anxiety over possible adverse effects. Education about safe use of TCS to minimize adverse reactions and the rebound phenomenon is necessary. TCI can also be safely used for skin inflammation.

TCSs: TCSs have been the mainstay of treatment of inflammation and are usually divided into grades 1-4 by their strength: mild, moderate, strong and very strong ointments, respectively. The therapeutic effect of TCSs is obvious for early and progressive lesions of acute symptom. While TCSs of grades 1-2 are known to have a very low risk of adverse effects, the safest method of drug administration should be considered. For application of TCS in the early stages of acute symptoms, a morning dose and stepwise dose reduction and discontinuance have been suggested and used [53]. It is also important to use the appropriate amount of TCS. The "fingertip unit" is helpful for this purpose [54]. Although disease in most patients can be controlled by TCS, the following should be considered if the patient does not show improvement. Was step 1 management performed thoroughly? Are the type and dosage of medications appropriate? Is there an associated complication such as infection? Is lichenification progressing? Is the lesion from another disease?

TCIs: The TCIs are steroid-free therapeutic agents used effectively and safely to treat the inflammation of AD. Pimecrolimus (Elidel®; Novartis, Switzerland) and tacrolimus (Protopic®; Astellas, USA) have shown immunomodulatory effects in AD [55]. Both pimecrolimus cream (1%) and tacrolimus ointment (0.03%) have been approved in the USA, Europe, and Korea for use in children older than two years [56]. The most common side effect of TCIs is a transient burning sensation of the skin. TCIs can be used as an alternative for treatment of sensitive skin areas such as the face and intertrigo because they have a low tendency to cause skin atrophy [57].

For the progressive lesion of acute symptom, the wet dressing is commonly recommended. Leung developed an advanced type of wet dressing, wet wrap therapy [58]. It is very helpful to reduce pruritus and inflammation by cooling the skin and to improve the penetration of TCS. The wrappings also act as a temporary protective barrier from the trauma associated with scratching.

The thickened skin in chronic AD lesions decreases the absorption of TCSs and moisturizers, making treatment difficult. In this case, adjuvant application of topical keratolytic agents can be used, taking care not to allow the agents into the eyes.

Step 3 therapy should be applied when there is no improvement even after following step 1 and step 2 managements. Oral or intravenous administration of CS is classified as step 3 therapy. Cyclosporin A, interferon gamma injection and UV therapies are also included in this stage. Other investigational treatments such as omalizumab, intravenous immunoglobulin and herbal medicines may also be included.

Most patients with severe symptoms improve clinically with rigorous performance of step 1 and step 2 managements, so step 3 therapy should be considered very carefully. Investigational treatments may be moved into step 2 after stringent verification to generalize their effects.

As is the process for the treatment of other chronic diseases, the goal of AD management should be established (Fig. 6). In infants, the treatment goal is to reduce the usually severe symptoms of AD occurring in this period. In children 2-3 years old, AD tends to improve naturally and this improvement can be expected. In the preschool period, efforts to prevent other allergic diseases should be made because 60-70% of the cases of BA and AR develop before five years of age [59].

The ultimate goals of this guideline are to decrease the incidence of not only AD but also BA and AR in community, to decrease the suffering of patients and their guardians and to induce a natural outgrow of AD.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Korean data on prevalence of atopic dermatitis by age in 2008. These data were provided by the Korean National Health Insurance Corporation. The patients were diagnosed by clinicians, including pediatricians, dermatologists, internists, family physicians and traditional medicine practitioners.

Fig. 2

Prevalence of atopic dermatitis (AD) in children aged 6-11 years in Seoul between 1995 and 2005. The one-year point prevalence (treatment of AD, last 12 months) was about 50% of the cumulative prevalence (diagnosis of AD, ever).

Fig. 3

The multifactorial pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis (AD). The mechanisms for the development of AD involve complex interactions between susceptibility genes, immaturity and/or abnormality in barrier function and environmental factors.

Fig. 4

Food sensitization rates in patients with atopic dermatitis (AD). Egg-white-specific IgE was detected in 24.3% of patients with AD followed by wheat-, milk-, peanut- and soy-specific IgE in order of decreasing frequency.

Fig. 5

Basic framework of the stepwise management in the atopic dermatitis organizer (ADO) guideline. The contents of this ADO guideline basically consist of 3 steps approaches: conservative management, topical anti-inflammatory therapy, and systemic anti-inflammatory therapy. IVIG: intravenous immunoglobulin.

Fig. 6

The management target curve. The treatment goals are to decrease the incidence of atopic dermatitis (AD), to decrease the suffering of patients and their guardians and to induce a natural outgrow of AD. Black line indicates the incidence of AD by age, and green line indicates the natural clinical course of AD.

References

1. Johansson SG, Hourihane JO, Bousquet J, Bruijnzeel-Koomen C, Dreborg S, Haahtela T, Kowalski ML, Mygind N, Ring J, van Cauwenberge P, van Hage-Hamsten M, Wüthrich B. A revised nomenclature for allergy. An EAACI position statement from the EAACI nomenclature task force. Allergy. 2001. 56:813–824.

2. Purvis DJ, Thompson JM, Clark PM, Robinson E, Black PN, Wild CJ, Mitchell EA. Risk factors for atopic dermatitis in New Zealand children at 3.5 years of age. Br J Dermatol. 2005. 152:742–749.

3. Asher MI, Montefort S, Björkstén B, Lai CK, Strachan DP, Weiland SK, Williams H. ISAAC Phase Three Study Group. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC Phases One and Three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet. 2006. 368:733–743.

4. Williams H, Stewart A, von Mutius E, Cookson W, Anderson HR. International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Phase One and Three Study Groups. Is eczema really on the increase worldwide? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008. 121:947–954.

5. Lee JH, Kim EH, Cho JB, Kim HY, Suh JM, Ahn KM, Cheong HK, Lee SI. Comparison of prevalence and risk factors of atopic dermatitis by physical examination and questionnaire survey in elementay school children. Pediatr Allergy Respir Dis. 2011. (Unpublished data).

6. Kay J, Gawkrodger DJ, Mortimer MJ, Jaron AG. The prevalence of childhood atopic eczema in a general population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994. 30:35–39.

7. Rudolph AM. . Rudolph's pediatrics. 1991. 19th ed. Norwalk: Appleton & Lange.

8. Illi S, von Mutius E, Lau S, Nickel R, Grüber C, Niggemann B, Wahn U. Multicenter Allergy Study Group. The natural course of atopic dermatitis from birth to age 7 years and the association with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004. 113:925–931.

9. Hong SJ. Korean ISAAC committee in Korean academy of pediatric allergy and respiratory disease. Report from Korean ISAAC committee. Pediatr Allergy Respir Dis. 2007. 17:S55–S66.

10. Novak N, Kruse S, Potreck J, Maintz L, Jenneck C, Weidinger S, Fimmers R, Bieber T. Single nucleotide polymorphisms of the IL18 gene are associated with atopic eczema. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005. 115:828–833.

11. Weidinger S, Klopp N, Rummler L, Wagenpfeil S, Novak N, Baurecht HJ, Groer W, Darsow U, Heinrich J, Gauger A, Schafer T, Jakob T, Behrendt H, Wichmann HE, Ring J, Illig T. Association of NOD1 polymorphisms with atopic eczema and related phenotypes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005. 116:177–184.

12. Weidinger S, Rümmler L, Klopp N, Wagenpfeil S, Baurecht HJ, Fischer G, Holle R, Gauger A, Schäfer T, Jakob T, Ollert M, Behrendt H, Wichmann HE, Ring J, Illig T. Association study of mast cell chymase polymorphisms with atopy. Allergy. 2005. 60:1256–1261.

13. Akdis CA, Akdis M, Bieber T, Bindslev-Jensen C, Boguniewicz M, Eigenmann P, Hamid Q, Kapp A, Leung DY, Lipozencic J, Luger TA, Muraro A, Novak N, Platts-Mills TA, Rosenwasser L, Scheynius A, Simons FE, Spergel J, Turjanmaa K, Wahn U, Weidinger S, Werfel T, Zuberbier T. European Academy of Allergology. Clinical Immunology/American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology/PRACTALL Consensus Group. Diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in children and adults: European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology/American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology/PRACTALL Consensus Report. Allergy. 2006. 61:969–987.

14. Kim HY, Jang EY, Sim JH, Kim JH, Chung Y, Park SH, Hwang EM, Han Y, Ahn K, Lee SI. Effects of family history on the occurrence of atopic dermatitis in infants. Pediatr Allergy Respir Dis. 2009. 19:106–114.

15. Okada H, Kuhn C, Feillet H, Bach JF. The 'hygiene hypothesis' for autoimmune and allergic diseases: an update. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010. 160:1–9.

16. Williams H, Flohr C. How epidemiology has challenged 3 prevailing concepts about atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006. 118:209–213.

17. Zutavern A, Hirsch T, Leupold W, Weiland S, Keil U, von Mutius E. Atopic dermatitis, extrinsic atopic dermatitis and the hygiene hypothesis: results from a cross-sectional study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005. 35:1301–1308.

18. Ibargoyen-Roteta N, Aguinaga-Ontoso I, Fernandez-Benitez M, Marin-Fernandez B, Guillen-Grima F, Serrano-Monzo I, Hermoso-demendoza J, Brun-Sandiumetge C, Ferrer-Nadal A, Irujo-Andueza A. Role of the home environment in rhinoconjunctivitis and eczema in schoolchildren in Pamplona, Spain. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2007. 17:137–144.

19. Galeev KA, Khakimova RF. Relationship of the ambient air concentrations of chemical substances to the spread of allergic diseases in children. Gig Sanit. 2002. 23–24.

20. Solé D, Camelo-Nunes IC, Wandalsen GF, Pastorino AC, Jacob CM, Gonzalez C, Wandalsen NF, Rosário Filho NA, Fischer GB, Naspitz CK. Prevalence of symptoms of asthma, rhinitis, and atopic eczema in Brazilian adolescents related to exposure to gaseous air pollutants and socioeconomic status. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2007. 17:6–13.

21. Huss-Marp J, Eberlein-König B, Breuer K, Mair S, Ansel A, Darsow U, Krämer U, Mayer E, Ring J, Behrendt H. Influence of short-term exposure to airborne Der p 1 and volatile organic compounds on skin barrier function and dermal blood flow in patients with atopic eczema and healthy individuals. Clin Exp Allergy. 2006. 36:338–345.

22. Ring J, Eberlein-Koenig B, Behrendt H. Environmental pollution and allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2001. 87:2–6.

23. Eberlein-König B, Przybilla B, Kühnl P, Pechak J, Gebefügi I, Kleinschmidt J, Ring J. Influence of airborne nitrogen dioxide or formaldehyde on parameters of skin function and cellular activation in patients with atopic eczema and control subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998. 101:141–143.

24. Sampson HA. The immunopathogenic role of food hypersensitivity in atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh). 1992. 176:34–37.

26. Nomura I, Goleva E, Howell MD, Hamid QA, Ong PY, Hall CF, Darst MA, Gao B, Boguniewicz M, Travers JB, Leung DY. Cytokine milieu of atopic dermatitis, as compared to psoriasis, skin prevents induction of innate immune response genes. J Immunol. 2003. 171:3262–3269.

27. Suh L, Coffin S, Leckerman KH, Gelfand JM, Honig PJ, Yan AC. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization in children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008. 25:528–534.

28. Palmer CN, Irvine AD, Terron-Kwiatkowski A, Zhao Y, Liao H, Lee SP, Goudie DR, Sandilands A, Campbell LE, Smith FJ, O'Regan GM, Watson RM, Cecil JE, Bale SJ, Compton JG, DiGiovanna JJ, Fleckman P, Lewis-Jones S, Arseculeratne G, Sergeant A, Munro CS, El Houate B, McElreavey K, Halkjaer LB, Bisgaard H, Mukhopadhyay S, McLean WH. Common loss-of-function variants of the epidermal barrier protein filaggrin are a major predisposing factor for atopic dermatitis. Nat Genet. 2006. 38:441–446.

29. Müller S, Marenholz I, Lee YA, Sengler C, Zitnik SE, Griffioen RW, Meglio P, Wahn U, Nickel R. Association of Filaggrin loss-of-function-mutations with atopic dermatitis and asthma in the Early Treatment of the Atopic Child (ETAC) population. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2009. 20:358–361.

30. Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh). 1980. 92:44–47.

31. Staldera JF, Taïebb A. Severity scoring of atopic dermatitis: the SCORAD index. Consensus report of the European task force on atopic dermatitis. Dermatology. 1993. 186:23–31.

32. Hanifin JM, Cooper KD, Ho VC, Kang S, Krafchik BR, Margolis DJ, Schachner LA, Sidbury R, Whitmore SE, Sieck CK, Van Voorhees AS. Guidelines of care for atopic dermatitis, developed in accordance with the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD)/American Academy of Dermatology Association "Administrative Regulations for Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines". J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004. 50:391–404.

33. Chamlin SL, Frieden IJ, Fowler A, Williams M, Kao J, Sheu M, Elias PM. Ceramide-dominant, barrier-repair lipids improve childhood atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2001. 137:1110–1112.

34. Grimalt R, Mengeaud V, Cambazard F. Study Investigator's Group. The steroid-sparing effect of an emollient therapy in infants with atopic dermatitis: a randomized controlled study. Dermatology. 2007. 214:61–67.

35. Anderson PC, Dinulos JG. Atopic dermatitis and alternative management strategies. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009. 21:131–138.

36. Kim MB, Kim BJ, Seo YJ, Lee YW, Lee AY, Kim KH, Kim MN, Kim JW, Ro YS, Park YM, Park CW, Seo SJ, Lee KH, Cho SH, Choi JH. Skin care for atopic dermatitis. Korean J Dermatol. 2009. 47:531–538.

37. Kim JY, Kwon JH, Ahn SH, Lee SI, Han YS, Choi YO, Lee SY, Ahn KM, Ji GE. Effect of probiotic mix (Bifidobacterium bifidum, Bifidobacterium lactis, Lactobacillus acidophilus) in the primary prevention of eczema: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010. 21:e386–e393.

38. Kim TH, Jung HH, Kim ES, Park JY, Kim KW, Sohn MH, Kim KE. A case of rice allergy caused by thin rice porridge during the weaning period. Pediatr Allergy Respir Dis. 2007. 17:149–154.

39. Ahn YH, Yeo JS, Lee JY, Han YS, Ahn KM, Lee SI. Effects of cooking methods on peanut allergenicity. Pediatr Allergy Respir Dis. 2009. 19:233–240.

40. Scalabrin DM, Bavbek S, Perzanowski MS, Wilson BB, Platts-Mills TA, Wheatley LM. Use of specific IgE in assessing the relevance of fungal and dust mite allergens to atopic dermatitis: a comparison with asthmatic and nonasthmatic control subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999. 104:1273–1279.

41. Mitchell EB, Crow J, Chapman MD, Jouhal SS, Pope FM, Platts-Mills TA. Basophils in allergen-induced patch test sites in atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 1982. 1:127–130.

42. Tan BB, Weald D, Strickland I, Friedmann PS. Double-blind controlled trial of effect of housedust-mite allergen avoidance on atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 1996. 347:15–18.

43. Platts-Mills TA, Mitchell EB, Rowntree S, Chapman MD, Wilkins SR. The role of dust mite allergens in atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1983. 8:233–247.

44. Capristo C, Romei I, Boner AL. Environmental prevention in atopic eczema dermatitis syndrome (AEDS) and asthma: avoidance of indoor allergens. Allergy. 2004. 59:Suppl 78. 53–60.

46. August PJ. The environmental causes and management of eczema. Practitioner. 1987. 231:495–500.

47. Zingarelli G, editor. Atopic dermatitis. Australian doctor - How to treat. Available from: http://www.australiandoctor.com.au//htt/pdf/AD_029_036_APR16_10.pdf.

48. Wahlgren CF, Hägermark O, Bergström R. The antipruritic effect of a sedative and a non-sedative antihistamine in atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1990. 122:545–551.

49. Harper J, Oranje AP, Prose NS. Textbook of pediatric dermatology. 2000. 1st ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science.

50. Seidenari S, Giusti G. Objective assessment of the skin of children affected by atopic dermatitis: a study of pH, capacitance and TEWL in eczematous and clinically uninvolved skin. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995. 75:429–433.

51. Ong PY, Ohtake T, Brandt C, Strickland I, Boguniewicz M, Ganz T, Gallo RL, Leung DY. Endogenous antimicrobial peptides and skin infections in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2002. 347:1151–1160.

52. Scheynius A, Johansson C, Buentke E, Zargari A, Linder MT. Atopic eczema/dermatitis syndrome and Malassezia. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2002. 127:161–169.

53. Thomas KS, Armstrong S, Avery A, Po AL, O'Neill C, Young S, Williams HC. Randomised controlled trial of short bursts of a potent topical corticosteroid versus prolonged use of a mild preparation for children with mild or moderate atopic eczema. BMJ. 2002. 324:768.

54. Long CC, Finlay AY. The finger-tip unit--a new practical measure. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1991. 16:444–447.

55. Hultsch T, Kapp A, Spergel J. Immunomodulation and safety of topical calcineurin inhibitors for the treatment of atopic dermatitis. Dermatology. 2005. 211:174–187.

56. Wahn U, Bos JD, Goodfield M, Caputo R, Papp K, Manjra A, Dobozy A, Paul C, Molloy S, Hultsch T, Graeber M, Cherill R, de Prost Y. Flare Reduction in Eczema with Elidel (Children) Multicenter Investigator Study Group. Efficacy and safety of pimecrolimus cream in the long-term management of atopic dermatitis in children. Pediatrics. 2002. 110:e2.

57. Queille-Roussel C, Paul C, Duteil L, Lefebvre MC, Rapatz G, Zagula M, Ortonne JP. The new topical ascomycin derivative SDZ ASM 981 does not induce skin atrophy when applied to normal skin for 4 weeks: a randomized, double-blind controlled study. Br J Dermatol. 2001. 144:507–513.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download