This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

QT prolongation is an electrocardiographic change that can lead to lethal arrhythmia. Acquired QT prolongation is known to be caused by drugs and electrolyte abnormalities. We report three cases in which the prolonged QT interval was improved at the time of operation by briefly discontinuing the drugs suspected to have caused the QT prolongation observed on preoperative electrocardiography. The QTc of cases 1, 2, and 3 improved from 518 to 429 ms, 463 to 441 ms, and 473 to 443 ms on discontinuing the use of a gastrointestinal prokinetic agent, a proton pump inhibitor, and a molecular targeted drug, respectively. These cases were considered to have drug-induced QT prolongation. We reaffirmed that even drugs administered for conditions unrelated to cardiac diseases can have adverse side effect of QT prolongation. In conclusion, our cases indicate that dental surgeons should be aware of the dangerous and even potentially lethal side effects of QT prolongation. For safe oral and maxillofacial surgery, cooperation with medical departments in various fields is important.

Go to :

Keywords: Drug-induced QT Prolongation, Lethal Arrhythmia, Pre-operative evaluation

QT prolongation occurs when the QT interval on electrocardiography is longer than 460 ms or when the QT time interval corrected by the RR interval (i.e., the QTc) extends to 440 ms or more despite the absence of an organic heart disease. QT prolongation is an electrocardiographic change that can lead to a lethal arrhythmia [

1]. It can be caused by a relatively rare congenital condition or through an acquired condition. Acquired QT prolongation is known to be caused by drug and electrolyte abnormalities (hypokalemia, hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia), myocardial ischemia or infarction, myocarditis, bradycardia, left ventricular dysfunction, and/or mitral regurgitation [

23]. Torsades de pointes (TdP) is known to occur with β-receptor stimulation while the QT time is prolonged [

4]. In addition, premature ventricular contractions, such as R on T, can lead to ventricular fibrillation.

We report three cases in which the prolonged QT interval improved at the time of operation by briefly discontinuing the drugs suspected to have caused the QT prolongation observed on preoperative electrocardiography.

CASE REPORT

1. Case 1

An 84-year-old male patient was scheduled to undergo tumor resection in the left cheek mucosa under intravenous sedation. His medical history included type 2 diabetes mellitus, pancreatic cancer resection, and retrograde bile duct disease.

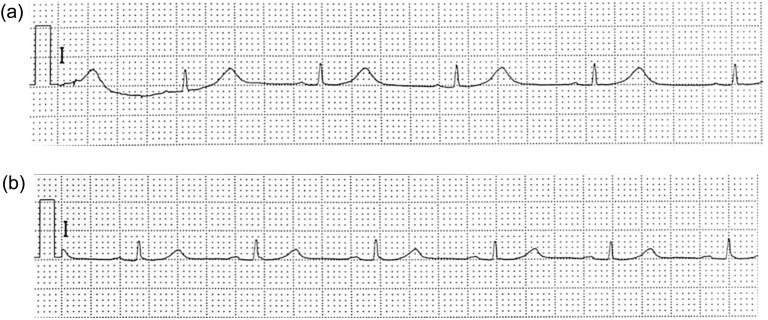

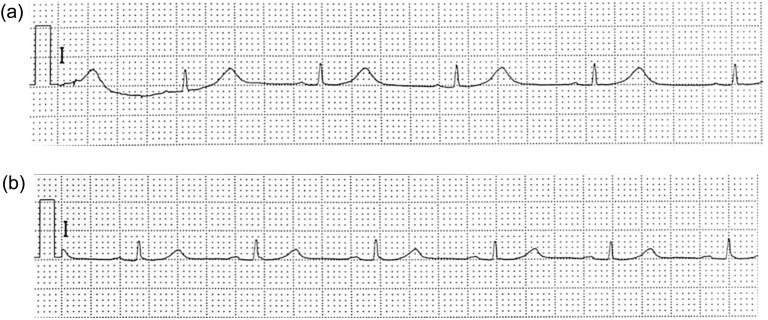

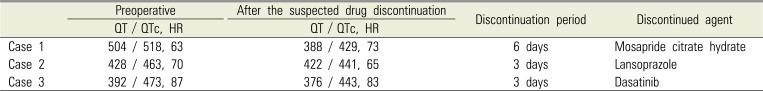

On preoperative electrocardiography, the QTc was 518 ms, which indicated QT prolongation. Blood examination did not show any disturbance related to electrolyte balance. Among the patient's regular medications, only mosapride citrate hydrate (mosapride) could cause QT-interval prolongation. We obtained permission from the patient's family physician to discontinue the patient's internal use of mosapride. Electrocardiography performed 6 days after mosapride discontinuation showed a QTc of 429 ms, which was within the normal range (

Tables 1 and

2,

Fig. 1a, 1b).

| Fig. 1Electrocardiogram of case 1 (a) at first visit and (b) on day 6 after cessation of mosapride citrate hydrate.

|

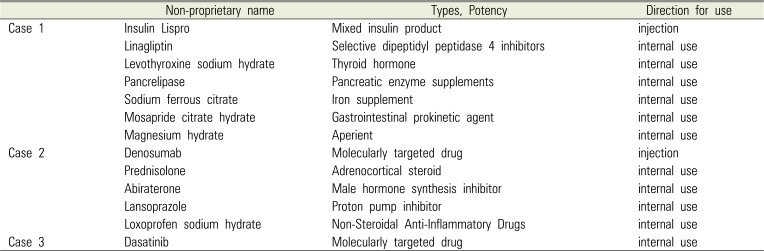

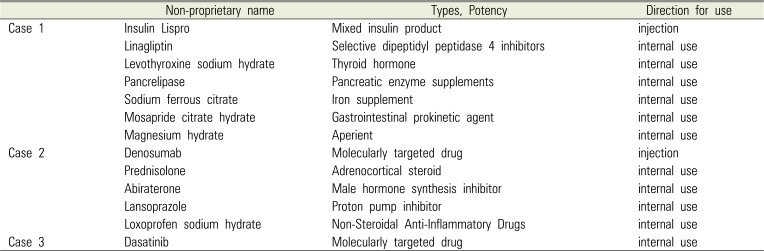

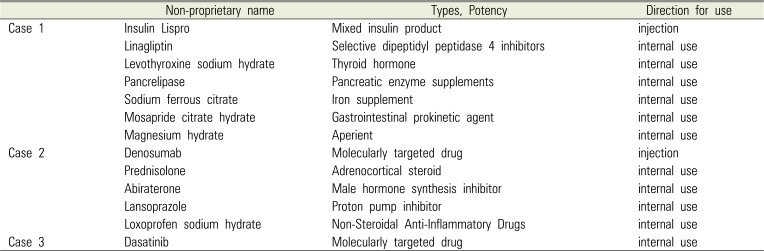

Table 1

Regular medication

|

Non-proprietary name |

Types, Potency |

Direction for use |

|

Case 1 |

Insulin Lispro |

Mixed insulin product |

injection |

|

Linagliptin |

Selective dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors |

internal use |

|

Levothyroxine sodium hydrate |

Thyroid hormone |

internal use |

|

Pancrelipase |

Pancreatic enzyme supplements |

internal use |

|

Sodium ferrous citrate |

Iron supplement |

internal use |

|

Mosapride citrate hydrate |

Gastrointestinal prokinetic agent |

internal use |

|

Magnesium hydrate |

Aperient |

internal use |

|

Case 2 |

Denosumab |

Molecularly targeted drug |

injection |

|

Prednisolone |

Adrenocortical steroid |

internal use |

|

Abiraterone |

Male hormone synthesis inhibitor |

internal use |

|

Lansoprazole |

Proton pump inhibitor |

internal use |

|

Loxoprofen sodium hydrate |

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs |

internal use |

|

Case 3 |

Dasatinib |

Molecularly targeted drug |

internal use |

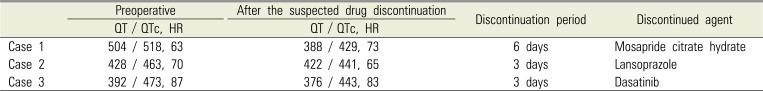

Table 2

Case summary

|

Preoperative |

After the suspected drug discontinuation |

Discontinuation period |

Discontinued agent |

|

QT/QTc, HR |

QT/QTc, HR |

|

Case 1 |

504 / 518, 63 |

388 / 429, 73 |

6 days |

Mosapride citrate hydrate |

|

Case 2 |

428 / 463, 70 |

422 / 441, 65 |

3 days |

Lansoprazole |

|

Case 3 |

392 / 473, 87 |

376 / 443, 83 |

3 days |

Dasatinib |

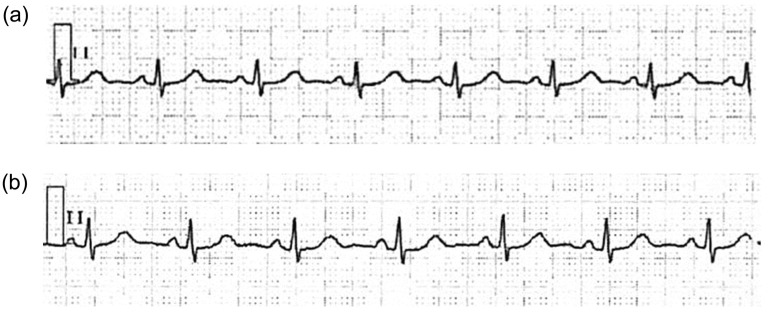

2. Case 2

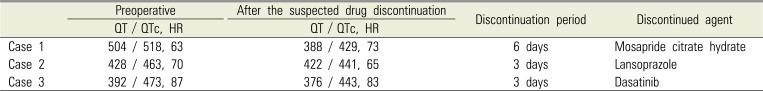

A 61-year-old man with a medical history of prostatic carcinoma was receiving once-monthly subcutaneous injections of the molecular targeted drug denosumab. He was scheduled to undergo right mandibular bone marrow curettage for drug-related jaw osteonecrosis while under general anesthesia. Preoperative electrocardiography revealed mild QT prolongation based on a QTc of 463 ms. Blood examination showed no abnormal findings. The drugs possibly causing QT prolongation were narrowed down to denosumab and to lansoprazole, an orally administered proton pump inhibitor. We ordered the discontinuation of lansoprazole. The QTc on electrocardiography 3 days after discontinuation improved to 441 ms (

Tables 1 and

2,

Fig. 2a, 2b).

| Fig. 2Electrocardiogram of case 2 (a) at first visit and (b) on day 3 after cessation of lansoprazole.

|

3. Case 3

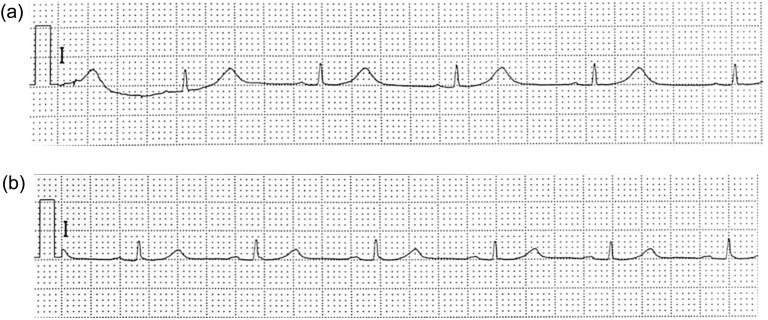

A 63-year-old man was scheduled to undergo cystectomy of a dentigerous cyst on the left lower wisdom tooth under general anesthesia. He was in the remission phase of chronic myelocytic leukemia and was taking 100 mg/day dasatinib orally. His platelets were not decreased, and there were no electrolyte abnormalities, but the QTc was 473 ms on electrocardiography, indicating QT prolongation. After consulting with his family physician, we decided to discontinue the oral administration of dasatinib 3 days before hospitalization. Electrocardiography at the time of hospitalization revealed that the QTc had improved to 443 ms (

Tables 1 and

2,

Fig. 3a, 3b).

| Fig. 3Electrocardiogram of case 3 (a) at first visit and (b) on day 3 after cessation of dasatinib.

|

All three patients were able to undergo the scheduled surgery without complications, under proper anesthesia management and using appropriate monitors (electrocardiogram, SpO2 monitor, and noninvasive blood pressure monitor).

Go to :

DISCUSSION

Aside from anti-arrhythmic agents, non-cardiovascular-related drugs, including antibiotics, antimycotics, antiallergic drugs, gastrointestinal prokinetic agents, and others, can cause QT prolongation. Antibiotics, such as macrolides, which have been suspected of prolonging the QT interval, are frequently used in the field of oral surgery.

Even if the QT prolongation caused by a single factor is mild, it may worsen if multiple factors overlap. Drug-induced QT prolongation is known to normalize when triggers, such as the causative drugs, are removed [

56].

Accelerators of QT prolongation include diabetes mellitus, advanced age, obesity, and hypothyroidism [

7]. In our cases, a gastrointestinal prokinetic agent, a proton pump inhibitor, and a molecular targeted drug were suspected to prolong the QT interval. Mosapride, the suspected causative drug in case 1, has been known to act as a selective 5-HT4-receptor agonist, although reports of QT prolongation are rare [

8]. The patient in case 1 was thought to be predisposed to develop QT prolongation because of diabetes mellitus and his advanced age. Close electrocardiogram monitoring is not likely performed in patients without organic heart failure who are administered antibiotics or gastrointestinal prokinetic agents. Thus, our results reaffirm that even drugs administered for conditions unrelated to cardiac diseases can have an adverse side effect of QT prolongation.

Lethal arrhythmia is highly likely to occur when the QT interval is prolonged (QTc interval > 500 ms) [

9]. Mild QT prolongation with a QTc interval < 500 ms does not necessarily indicate an urgent issue. However, a report noted that the risk of TdP increased when the QTc interval was extended by > 60 ms compared to that before drug administration [

10]. It should be remembered that in patients receiving drugs that can lead to drug-induced QT prolongation, interaction with anesthetics during surgery may promote QT prolongation and lead to lethal arrhythmia. It is important for surgeons to consult with the physicians who prescribed a suspected drug regarding medication discontinuation when trying to confirm the QT prolongation on electrocardiography before oral and maxillofacial surgery.

In conclusion, our cases indicate that dental surgeons should be aware of the dangerous and even potentially lethal side effects of QT prolongation. For a safe oral and maxillofacial surgery, cooperation with medical departments in various fields is important.

Go to :