Abstract

Programs provided by the Korea Association of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation include Basic Life Support (BLS), Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS), Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS), and Korean Advanced Life Support (KALS). However, programs pertinent to dental care are lacking. Since 2015, related organizations have been attempting to develop a Dental Advanced Life Support (DALS) program, which can meet the needs of the dental environment. Generally, for initial management of emergency situations, basic life support is most important. However, emergencies in young children mostly involve breathing. Therefore, physicians who treat pediatric dental patients should learn PALS. It is necessary for the physician to regularly renew training every two years to be able to immediately implement professional skills in emergency situations. In order to manage emergency situations in the pediatric dental clinic, respiratory support is most important. Therefore, mastering professional PALS, which includes respiratory care and core cases, particularly upper airway obstruction and respiratory depression caused by a respiratory control problem, would be highly desirable for a physician who treats pediatric dental patients. Regular training and renewal training every two years is absolutely necessary to be able to immediately implement professional skills in emergency situations.

Dentists who treat children and adolescents should be able to provide good quality treatment for patients who fear dental treatment, through appropriate behavioral management based on sufficient understanding of the emotional and psychological development of children. However, the dentist may consider sedation and general anesthesia when the child rejects treatment due to negative memories about dental care or severe fear, which make behavioral management impossible [1]. Therefore, the dentist must have knowledge, skill, and behavior that prepare for this possibility [23].

For the past 30 years, sedation has been widely used as an alternative to general anesthesia. In Korea, Choi and Shim [4] reported in 1999 that 29% of pediatric dentists use sedation, Ahn et al. [5] reported in 2005 that 66% use sedation, and Bae et al. [6] in 2014 reported use by 63% of the members of the Dental Society of Anesthesiology; therefore, the frequency of use appears to have leveled off. The rates have been relatively comparable to the 72.6% peak in 1985, 69.7% in 1991, 67.9% in 1995, and 68.8% in 2000 in a report by Houpt [7] on the use of sedation by pediatric dentists in the USA over a 15-year period. The stable rates may reflect the increased frequency of side effects, as sedation that began for behavioral and anxiety control exceeded the level of conscious sedation, and the depth of sedation increased. The amount, type, and mixtures of drugs used during sedation are related to the side effects [8]. In a survey of pediatric dentists who used sedation, Yang et al. [9] reported in 2014 that 88% had patients who experienced side effects such as nausea, vomiting, overexcitement, difficulty breathing, oversedation, foreign body aspiration, and drug allergy, among others. Most dental treatments involve procedures during which dentists invade the airway. Moreover, because various instruments are used, the possibility of foreign body aspiration is increased [10]. Serious complications during sedation include secondary brain damage, severe hypertension or hypotension, seizures, and cardiac arrest due to airway obstruction, laryngospasm, respiratory failure, or respiratory arrest [11]. In children, especially, cardiac arrest involves breathing and a narrowed airway [12]. While performing sedation, appropriate respiratory monitoring and airway placement are always necessary. The deeper the sedation level, the more decreased the airway protective reflex, and the greater the possibility of increased airway obstruction or foreign body aspiration [13]. Therefore, dentists who treat pediatric patients need sufficient preparation to appropriately handle this kind of emergency situation.

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation consists of Basic Life Support (BLS), with chest compression and rescue breathing for the patient in cardiac arrest, and drug administration, defibrillation, and Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support (ACLS) for integrated treatment after cardiac arrest [14]. ACLS for children is Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS). Emergency situations in pediatric dental clinic patients are mostly due to breathing difficulty. Therefore, appropriate emergency management in the dental clinic environment requires thorough understanding of PALS [15].

Interest in patient safety has recently increased, and PALS is actively recommended for emergency management in the treatment of pediatric dental patients with sedation.

Professional cardiopulmonary resuscitation involves defibrillation based on electrocardiogram rhythm analysis, advanced airway placement, drug administration, and endotracheal intubation, and secures intravenous or intraosseous access for drug administration while providing basic life support. The protocol during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: after performing chest compression and artificial respiration for 2 min, perform defibrillation if there is a shockable rhythm like ventricular fibrillation, pulseless ventricular tachycardia, etc., requiring monitored defibrillation according to electrocardiogram analysis; if a non-shockable rhythm is present, such as asystole, pulseless electrical activity, etc., that does not require monitored defibrillation, continue cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Vasopressors are administered to maintain perfusion pressure during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. The method of choice is repeated administration of 1.0 mg (adult standard) of epinephrine every 3-5 min.

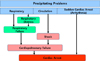

Cases in which heart disease is the cause of cardiac arrest are rare in children or infants, and asphyxial cardiac arrest resulting from respiratory failure, sepsis, etc., are more common. PALS deals with interventions to prevent progression to cardiac arrest; when a respiratory problem occurs, it may lead to respiratory distress and failure, and soon transitions to cardiac arrest; when a circulatory problem occurs, it can lead to shock and cardiac arrest; a heart problem proceeds directly to cardiac arrest. Fig. 1 shows the whole pathways in pediatric cardiac arrest.

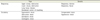

PALS is classified according to dyspnea, respiratory failure, and shock, and is a process that effectively diagnoses and intervenes in 12 emergency situations subdivided into 4 typical cases for each classification [16]. Table 1 shows the classification according to the type of each case.

In emergency intervention, clinical reasoning, judgment, and treatment ability are required, and the process of PALS divides these into stages: evaluate, identify, and intervene. One can evaluate and judge emergency situations according to system flow as in Fig. 2, and resolve problems by immediately repeating the process of intervening, with self-verification that nothing has been overlooked.

PALS emphasizes a system and team approach. In Fig. 3, we arranged the order for management of an emergency situation as used in PALS.

For a system approach, the initial impression about consciousness, respiration, and circulation in an emergency situation is important. Airway, breathing, circulation, body temperature, etc. comprise primary assessment. In secondary assessment, we collect and evaluate information about vital signs and symptoms, allergy status, whether or not the patient is taking medication, anamnesis, eating conditions, and appearance of the symptoms. Through an ongoing process, missing information will be obtained from laboratory data, radiographs, and other examinations. Even while going through each step, we can determine the type and severity of the current condition, and repeat the process of properly intervening according to the situation. Through these consecutive steps, we can arrive at the most appropriate definitive diagnosis and intervention. Table 2 presents this process.

Dentistry invades the airway due to the nature of treatment, and respiratory distress and failure are inseparable; the causes include upper airway obstruction, lower airway obstruction, disease of the pulmonary parenchyma, and respiratory control problems. In particular, properly dealing with upper airway obstruction caused by decreased consciousness related to sedation, and respiratory depression from pneumotaxic center suppression by the sedating drug, is necessary. Recently, as asthma and bronchiolitis cases increase, lower airway obstruction is becoming an important cause of respiratory failure. We also have to consider pneumonia, which is disease of the pulmonary parenchyma. In this situation, one has to administer oxygen and place an airway; respiratory failure requires both bag mask respiration and advanced airway placement. However, in the case of upper airway obstruction, management of respiratory distress and failure first requires airway placement; the cause of lower airway obstruction is a narrowed lower airway, and expansion using drugs and treatment of pulmonary parenchymal disease take priority. For problems caused by respiratory control failure, normal recovery of the suppressed pneumotaxic center becomes the ultimate focus of treatment.

When respiration and circulation rapidly worsen, we have to determine the cause and severity through a systemic judgment process, and immediately take appropriate measures. Each situation caused by respiration and circulation is organized according to type and severity in Table 3.

The first large classification is a case proceeding to an emergency situation because of a respiratory problem; each large classification is divided into 4 types by primary assessment according to upper airway obstruction, lower airway obstruction, lung tissue disease, and disordered control of breathing.

Depending on severity, differential diagnosis is simultaneously performed for respiratory distress and failure, with proper intervention.

The second large classification is shock, which is strongly correlated with circulation. Actually, most intensive care or emergency room patients correspond to the shock case. Although rarely seen in dental treatment situations, septic shock and shock caused by anaphylaxis can occur. As heart surgery and treatment have advanced, the number of children who have well-controlled heart disease has also increased. Therefore, there is a need to be well-informed about cardiogenic shock. When faced with shock in PALS, we separate 4 types as above, and suggest immediate intervention by differentiating between compensated and hypotensive shock, depending on severity.

The last large classification is strongly associated with cardiac arrest. Sudden arrhythmia and cardiac arrest can occur in any patient, so there is a need to systematically prepare for them. When cardiac arrest occurs, the algorithm is the same as for an adult. However, the first difference is in the amount of drug used: 0.01 mg/kg epinephrine and 5 mg/kg amiodarone. Second, when defibrillation is needed, one can start with 2-4 J/kg, and then 4 J/kg, up to a maximum of 10 J/kg.

Fig. 4 shows the systemic flowchart for pediatric cardiac arrest treatment.

The International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) was established in 1992, and establishes and announces guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Groups such as the American Heart Association (AHA), European Resuscitation Council (ERC), Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (HSFC), Australian and New Zealand Committee on Resuscitation (ANZCOR), Resuscitation Councils of Southern Africa (RCSA), Inter American Heart Foundation (IAHF), and Resuscitation Council of Asia (RCA) participate in ILCOR; since 2000, they have announced new guidelines every 5 years [17]. Korea belongs to the RCA, participating since 2000 in important decision-making, and was actively involved in announcing a new guideline in 2015.

The Korea Association of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation entered into an agreement with the AHA and International Training Organization (ITO) in 2004 and supervises education and eligibility. Programs provided include Basic Life Support, ACLS, PALS, and Korean Advanced Life Support (KALS). However, programs pertinent to dental care are lacking. Since 2015, related organizations have been attempting to develop a Dental Advanced Life Support (DALS) program, which can meet the needs of the dental environment.

In order to manage emergency situations in the pediatric dental clinic, respiratory support is most important. Therefore, mastering professional PALS, which includes respiratory care and core cases, particularly upper airway obstruction and respiratory depression caused by a respiratory control problem, would be highly desirable for a physician who treats pediatric dental patients. Regular training and renewal training every two years is absolutely necessary to be able to immediately implement professional skills in emergency situations.

Figures and Tables

Table 1

Core cases of PALS [16]

Table 2

The clinical assessment flowchart [16]

Table 3

Type and severity of the problem [16]

References

1. Wilson S, Farrell K, Griffen A, Coury D. Conscious sedation experiences in graduate pediatric dentistry programs. Pediatr Dent. 2001; 23:307–314.

2. Kim S, Kim J. Introduction of sedation guidelines and need for sedationist. J Korean Acad Pediatr Dent. 2012; 39:314–324.

3. Kim J, Yoo S, Kim J. The qualification of dentist for sedation: BLS and ACLS. J Korean Acad Pediatr Dent. 2015; 42:80–86.

4. Choi YS, Shim YS. Sedation Practices in Dental Office: A Survey of Members of the Korean Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. J Korean Acad Pediatr Dent. 1999; 26:579–588.

5. An SY, Choi BJ, Kwak JY, Kang JW, Lee JH. A survey of sedation practices in the Korean pediatric dental office. J Korean Acad Pediatr Dent. 2005; 32:444–453.

6. Bae CH, Kim H, Cho KA, Kim MS, Seo KS, Kim HJ. A Survey of Sedation Practices in Korean Dentistry. J Korean Dent Soc Anesthesiol. 2014; 14:29–39.

7. Houpt M. Project USAP 2000-use of sedative agents by pediatric dentists: a 15-year follow-up survey. Pediatr Dent. 2002; 24:289–294.

8. Coté CJ, Karl HW, Notterman DA, Weinberg JA, McCloskey C. Adverse sedation events in pediatrics: analysis of medications used for sedation. Pediatrics. 2000; 106:633–644.

9. Yang Y, Shin T, Yoo S, Choi S, Kim J, Jeong T. Survey of sedation practices by pediatric dentists. J Korean Acad Pediatr Dent. 2014; 41:257–265.

10. Heo N, Lee K, An S, Song J, Shin G, Ra J. Aspiration and ingestion of foreign bodies in dental practice. J Korean Acad Pediatr Dent. 2015; 42:69–74.

11. D'Eramo EM. Mortality and morbidity with outpatient anesthesia: the Massachusetts experience. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999; 57:531–536.

12. Park YW. New Guideline of Pediatric Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. Korean J Pediatr. 2004; 47:591–595.

13. Cravero JP, Blike GT, Beach M, Gallagher SM, Hertzog JH, Havidich JE, et al. Incidence and nature of adverse events during pediatric sedation/anesthesia for procedures outside the operating room: report from the Pediatric Sedation Research Consortium. Pediatrics. 2006; 118:1087–1096.

15. Kim J. Application of a pediatric advanced life support in the situation of a dental treatment. J Korean Dent Assoc. 2015; 53:538–544.

16. Chameides L. Pediatric Advanced Life Support: Provider Manual. American Heart Association;2011.

17. ILCOR. International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) 2015. Available from: http://www.ilcor.org/about-ilcor/about-ilcor/.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download