This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

A 30-year-old female patient, 18 weeks gestational age, with no prior medical history was admitted to hospital complaining severe right upper quadrant pain. The patient was admitted to intensive care unit (ICU) after emergency surgery to treat intraperitoneal hemorrhage caused by rupture of liver hematoma. Despite the absence of high blood pressure, the patient was diagnosed with hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count (HELLP) syndrome on the basis of abnormal levels of blood aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase, lactate dehydrogenase, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, C-reactive protein (CRP) and platelet along with liver damage and proteinuria. While in ICU, the patient was given total parenteral nutrition (TPN) and enteral nutrition (EN) for –20 days because oral feeding was impractical. In the early stage, TPN supply was not sufficient to meet the elevated nutritional demand induced by disease and surgery. Nevertheless, continuous care of nutrition support team enabled satisfactory EN and, subsequently, oral feeding which led to improvement in patient outcome.

Keywords: HELLP syndrome, Nutrition support, Enteral nutrition, Parenteral nutrition

INTRODUCTION

Hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count (HELLP) syndrome is frequently associated with severe form of pre-eclampsia. However, the relationship between 2 symptoms is controversial, and the cause of HELLP syndrome is still unknown. But there is a growing consensus that it has a familial tendency [

12].

At present, 2 classification systems are used for the diagnosis of HELLP syndrome. Diagnostic criteria developed at the University of Tennessee are high lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (> 600 U/L), high aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (≥ 70 U/L) and low platelets (PLTs) (< 100,000/μL) [

34]. The Mississippi HELLP system further classifies the disorder by the PLT counts: 1) class I if PLTs count less than 50,000/μL; 2) class II if between 50,000/μL and 100,000/μL; and 3) class III if greater than 100,000/μL [

56].

HELLP syndrome is often regarded as acute rejection reaction to embryo implantation but the etiology is not fully understood. HELLP syndrome has an incidence rate ranging from 0.5%–0.9% in all pregnancies, and the rate increases up to 10%–20% in pregnant women with preeclampsia [

7]. Most of the patients demonstrate hypertension and proteinuria but 10%–20% does not show those symptoms. More than half of the patients experience weight gain and edema [

3]. Classic symptoms also include right upper quadrant pain, nausea, and vomiting [

38]. Serious symptoms requiring dialysis and/or mechanical ventilation necessitate admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) [

9]. Inadequate treatment of HELLP symptom may contribute to serious complications such as disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) syndrome, hepatic hematoma, cardioplegia, myocardial ischemia, adult respiratory distress syndrome, pulmonary edema, acute kidney failure, intra-uterine growth retardation (IUGR), and infant respiratory distress syndrome. Corticosteroid can be administered for the treatment of HELLP, still, parturition is the most effective method to avoid complications. Most of the symptoms wane 2–3 days postpartum [

10].

Nutritional management of inpatients has been shown to be important in recovery from various diseases. Poor nutritional status adversely affects health and recovery of the patients [

11]. Also, requirements of energy, protein and micronutrients are elevated in critically ill patients due to abnormal nutrient loss from diarrhea and vomiting, increased metabolic rate, electrolyte abnormality, infection, surgery, and trauma [

12]. Malnutrition in critically ill patients attenuates immune function and respiratory muscles. Respiratory muscle wasting leads to prolonged use of mechanical ventilation and ICU stay, complications related to infection and subsequently higher mortality. Therefore, nutrition support using enteral and parenteral nutrition (PN) is critical to prevent malnutrition in hospitalized patients with inadequate dietary intake. Goals of nutrition support for the critically ill patients include maintenance of lean body mass, enhancement of immune function, and prevention of metabolic complications. Tertiary hospitals in Korea are equipped with nutrition support team (NST) and strive for nutrition support for the hospitalized patients.

We report the case of rare HELLP syndrome patient who was admitted in ICU for –20 days and was under nutritional management focused on total parenteral nutrition (TPN), enteral nutrition (EN) and then successfully switched to oral feeding. We observed that NST care allowed stabilization of the symptoms of the patient and led to discharge without complications.

CASE

A 30-year-old female patient (gestational age: 18 weeks), with a history of pain in the right shoulder, nausea, and dyspepsia for 3 days, was admitted to hospital complaining severe right upper quadrant pain. Test results on admission are shown in

Table 1. After medical evaluation, the patient was diagnosed with intraperitoneal hemorrhage due to rupture of liver hematoma and taken to the operating room for an emergency operation. On the surgery, capsules filled with hematoma were observed near liver and gall bladder of the patient. After cholecystectomy, the patient was admitted to ICU.

Table 1

Clinical characteristics of the patient on admission

|

General characteristics |

Value |

|

Age, yr |

30 |

|

Sex |

Female |

|

Anthropometric indexes |

|

|

Height, cm |

159 |

|

Body weight, kg |

55 |

|

Body weight before pregnancy, kg |

51 |

|

Vital signs |

|

|

Body temperature, ℃ |

36 |

|

Pulse rate, bpm |

111 |

|

Systolic/diastolic blood pressure, mmHg |

72/42 |

Post-surgery blood test results showed that levels of AST/alanine aminotransferase (ALT), LDH, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, and C-reactive protein (CRP) were above normal range. On the contrary, levels of PLT, albumin, and cholesterol were lower than normal. Despite the absence of high blood pressure, the patient was diagnosed with HELLP syndrome based on lab test results, liver damage, and proteinuria. On day 2 after admission, the patient gave birth to a stillborn baby.

The patient was initially fasted and was supported by central PN at day 4. On day 9, second surgery was performed to remove hematoma and then referred to NST. On referral to NST, the patient's nutritional status was moderate malnutrition based on over 7 days of “nil per os (nothing by mouth [NPO])” and moderate accumulation of fluids. And the patient was on TPN (Combiflex lipid 1,000 inj [central] [JW Pharmaceutical, Seoul, Korea]; infusion rate 40 mL/hr) and was given 1,080 kcal energy and 36 g protein daily. This is far less than required doses of 1,540–1,650 kcal and 72–82 g protein, calculated on the basis of initial body weight and hyper-metabolism (55 kg, 28–30 kcal/kg, 1.3–1.5 g protein/kg). The progression of nutritional support and clinical aspects of the patient during admission was shown in

Figure 1.

| Figure 1

Progression of nutritional support and clinical aspects of the patient.

HOD, hospital onset of day; NST consult, nutrition support team consult; NSVD, normal spontaneous vaginal delivery; TPN, total parenteral nutrition.

|

TPN was continued because gastroenteral feeding was restricted by surgery and high gastric output. It was judged that TPN in use (Combiflex lipid 1,000 inj [central]; JW Pharmaceutical) could not meet the high protein demand induced by severe infection and high body fluid output from gastric drainage and hemovac drain. However, the patient could not receive large amount of TPN because she was on fluid restriction for the management of severe edema and liver failure. To resolve this situation, NST suggested alternative TPN (SmofKabiven inj 1,500 [central] [Fresenius Kabi AB, Uppsala, Sweden]; 0.8 bag/daily) which could provide higher amount of protein and micro minerals such as zinc, which is necessary for immune function and wound healing. In addition, NST recommended adding an ample of vitamin mixture (Tamipool inj; Celltrion Pharm Inc., Cheongju, Korea) to TPN. However, the patient remained on the previous TPN. On day 13, the patient's body weight was estimated to be 63–66 kg due to edema.

On day 15 (5 days after second surgery), the patient was referred to NST for EN. NST evaluated the patient's nutritional status and classified the status into moderate malnutrition state on the basis of poor energy supply below 75% of the requirement for > 7 days and the edema. Since the patient had edema, nutrition requirement was calculated based upon ideal body weight, not actual body weight. At this point, estimated energy requirement to avoid overfeeding was 1,328–1,593 kcal (25–30 kcal/kg) and protein requirement was 64–80 g (1.2–1.5 g/kg). Again, protein composition of standard enteral formula was not sufficient to meet the demand, so NST advised to use high protein enteral formula.

From day 15, the amount of enteral formula gradually increased to reach 1,500 kcal/1,500 mL at day 20. The patient showed improvements and was extubated on day 19. Also, edema has subsided, and the patient weighed down to 50 kg. The energy and protein deliveries during hospital stay were shown in

Figures 2 and

3. During the first 2 weeks after ICU admission, the TPN amount was far less than the requirement, and thereafter the tube feeding amount was approached to the minimum requirement. On day 22, the patient was transferred to general ward. On day 24, oral feeding of clear liquid diet was initiated. The patient was referred to NST again. At this point, the patient experienced 10% weight loss from her initial body weight and weighed 49.5 kg. NST classified the patient into severe malnutrition state and calculated nutrition requirement based upon standard body weight (53.1 kg) to promote rapid recovery. NST estimated that energy requirement was 1,434–1,699 kcal (27–32 kcal/kg) and protein 58–64 g (1.1–1.2 g/kg). Afterwards the patient was fed general liquid diet. The patient could tolerate oral feeding and consumed 2/3 of liquid diet provided. NST suggested using oral nutrition supplement (Encover 200 mL [200 kcal, 7 g]; JW Pharmaceutical) to increase energy intake but this was not included in the diet regimen.

| Figure 2

The amount of energy delivery during hospital stays.

HOD, hospital onset of day.

|

| Figure 3

The amount of protein delivery during hospital stays.

HOD, hospital onset of day.

|

The patient was successfully switched to regular diet and was discharged without significant complications. At discharge, body weight was 47.4 kg following 13.8% weight loss during 1 month hospital stay. Two months after discharge, thorough checkup was performed at outpatient clinic and found improvements in liver function without specific symptoms other than mild fatty liver. All biochemical test results were negative for anomaly (

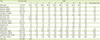

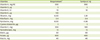

Table 2).

Table 2

Results of biochemical test of the patient

|

Test |

Normal range |

HOD |

|

1 |

4 |

7 |

10 |

13 |

16 |

19 |

22 |

24 |

29 |

Outpatient clinic |

|

CRP, mg/L |

0.1–6.0 |

39.0 |

197.7 |

266.1 |

253.6 |

218.8 |

185.5 |

79.0 |

42.9 |

40.6 |

7.7 |

- |

|

Albumin, g/dL |

3.4–5.3 |

2.8 |

2.9 |

2.7 |

2.8 |

2.9 |

3.2 |

3.2 |

3.5 |

3.3 |

3.9 |

4.2 |

|

Glucose, mg/dL |

80–118 |

115 |

84 |

119 |

105 |

122 |

208 |

142 |

136 |

110 |

101 |

64 |

|

Calcium, mg/dL |

8.6–10.0 |

7.1 |

8.1 |

8.2 |

7.4 |

8.2 |

8.9 |

9.4 |

9.6 |

9.2 |

9.7 |

9.6 |

|

Inorganic P, mg/dL |

2.8–4.5 |

2.7 |

2.8 |

2.5 |

2.2 |

2.7 |

2.4 |

3.6 |

3.7 |

5.0 |

4.1 |

4.2 |

|

Alk. Phos, IU/L |

35–83 |

103 |

103 |

82 |

92 |

199 |

264 |

292 |

292 |

266 |

272 |

95 |

|

AST (GOT), IU/L |

14–30 |

3,179 |

565 |

66 |

48 |

64 |

50 |

63 |

35 |

41 |

40 |

28 |

|

ALT (GPT), IU/L |

6–33 |

1,881 |

500 |

112 |

38 |

37 |

40 |

66 |

53 |

43 |

56 |

30 |

|

T. Bilirubin, mg/dL |

0.2–1.2 |

5.2 |

4.3 |

2.4 |

3.0 |

2.3 |

2.1 |

1.6 |

1.2 |

1.3 |

0.9 |

0.7 |

|

D. Bilirubin, mg/dL |

0.0–0.2 |

2.1 |

2.9 |

1.5 |

1.9 |

1.4 |

1.3 |

1.0 |

0.8 |

0.7 |

0.5 |

- |

|

Amylase, U/L |

25–97 |

211 |

53 |

86 |

108 |

68 |

73 |

117 |

127 |

123 |

88 |

- |

|

Lipase, U/L |

19–59 |

24 |

44 |

95 |

115 |

86 |

95 |

205 |

189 |

138 |

90 |

- |

|

BUN, mg/dL |

7.0–22.0 |

16.1 |

9.7 |

15.3 |

14.2 |

8.8 |

9.9 |

14.5 |

14.7 |

14.7 |

11.7 |

8.3 |

|

Creatinine, mg/dL |

0.65–1.10 |

0.52 |

0.48 |

0.41 |

0.27 |

0.18 |

< 0.20 |

0.20 |

0.24 |

0.41 |

0.42 |

0.60 |

|

Cholesterol, mg/dL |

139–230 |

65 |

80 |

76 |

94 |

169 |

212 |

230 |

225 |

227 |

265 |

202 |

|

Lymphocyte (#), 103/µL |

1.50–4.00 |

0.74 |

0.63 |

0.73 |

0.64 |

0.72 |

0.44 |

0.65 |

0.66 |

0.72 |

1.13 |

1.89 |

|

PLT count, 103/µL |

150–400 |

69 |

85 |

149 |

219 |

448 |

566 |

627 |

484 |

360 |

290 |

304 |

|

LDH, IU/L |

140–280 |

908 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Changes in clinical indices of nutritional status were shown in

Figure 4. Concentrations of plasma cholesterol and albumin are useful markers of nutritional status. Albumin level is a sensitive marker of visceral protein and may not represent whole body protein. Still it is useful in screening malnutrition. Also CRP level serves as markers of both inflammation and nutritional status. As shown in

Figure 4, plasma cholesterol and albumin levels were below normal range at the time of admission but have improved significantly during hospitalization. In early stage of hospital stay, CRP level was severely aberrant but returned to near normal range on discharge.

| Figure 4

Changes in the cholesterol, albumin, and serum CRP concentration of the patient.

CRP, C-reactive protein.

|

DISCUSSION

Subject of this case report was hospitalized for 34 days. During that period, the patient was under intensive care in ICU for 20 days. While in ICU, the subject was on enteral and PN due to difficulty in oral intake.

For majority of the surgical patients in ICU, NPO is recommended due to intraperitoneal surgery, enteroplegia, inflammation, and gastrointestinal hemorrhage. And the complications of surgery may lead to hyper-metabolism and subsequent malnutrition. These conditions necessitate proper PN for patients [

13]. The American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) guideline advises to deliver early nutrition support therapy, primarily by the enteral route, and start PN as early as possible when EN is not feasible in poorly nourished patients [

14]. The European Society of Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) also states that all patients who are not expected to be on normal nutrition within 3 days should receive PN within 24–48 hours if they cannot tolerate EN [

15]. The ESPEN guideline indicates that ICU patients should receive at least 25 kcal/kg/day to target over the next 2–3 days. They also should receive enough protein to meet their requirement from day 1 of ICU. As for the patient in this case report, PN was commenced on day 4 of hospitalization and lasted about 10 days. During that period, energy and protein supply was below 70% of the requirement and therefore could not meet the high metabolic demand after surgery.

Meticulous attention should be paid to mineral and electrolyte balance of the PN. Critically ill patients are prone to mineral deficiency due to higher requirement following massive loss from the body [

16]. Deficiencies of zinc, iron, selenium and vitamins A, B, C are quite common among the critically ill and these deficiencies can increase the risk of multiple organ failure, muscle wasting, delayed wound healing and impaired immune function [

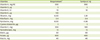

15]. When compared to guideline of American Society of Parenteral and Enteral (ASPEN) and recommendation from our own NST, administered TPN to the subject did not contain enough minerals and electrolytes (

Table 3). On the other hand, mineral contents of NST recommendation were comparable to the ASPEN guideline. Also it contained ample amount of zinc and other microminerals to help wound healing. Multivitamin injection (Tamipool inj 5 mL/V; Celltrion Pharm Inc.) suggested by NST could provide various vitamins to meet ASPEN guideline also (

Table 4). It is estimated that the subject could benefit from effective nutrition support if the TPN was adjusted according to NST recommendation from the early stage.

Table 3

Amounts of electrolytes and minerals in the used PN and recommended PN

|

Nutrients |

Requirement*

|

Used PN |

Recommended PN |

|

Combiflex lipid (1 L) |

SmofKabiven (1 L) |

|

Electrolytes |

Na, mEq |

55 (1–2 mEq/kg) |

28.0 |

40.6 |

|

K, mEq |

55 (1–2 mEq/kg) |

24.0 |

30.5 |

|

Mg, mEq |

8–20 |

4.0 |

10.1 |

|

Ca, mEq |

10–15 |

3.6 |

5.1 |

|

P, mmol |

20–40 |

12.0 |

12.8 |

|

Minerals |

Zn, mg |

2.5–5.0 |

- |

2.6 |

|

Cu, mg |

0.3–0.5 |

- |

- |

|

Se, µg |

20–60 |

- |

- |

|

Mn, mg |

0.06–0.10 |

- |

- |

|

Cr, µg |

10–15 |

- |

- |

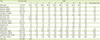

Table 4

Amounts of vitamins in Tamipool inj

|

Vitamins |

Requirement*

|

Tamipool inj |

|

Vitamin A, mg RE |

990 |

990 |

|

Vitamin D, µg |

5 |

5 |

|

Vitamin E, IU |

10 |

10 |

|

Vitamin K, µg |

150 |

- |

|

Thiamin, mg |

6.00 |

3.81 |

|

Riboflavin, mg |

3.6 |

3.6 |

|

Pyridoxine, mg |

6.00 |

4.86 |

|

Cyanocobalamin, µg |

5 |

5 |

|

Vitamin C, mg |

200 |

100 |

|

Pantothenate, mg |

15 |

15 |

|

Biotin, µg |

60 |

60 |

|

Folate, µg |

600 |

400 |

|

Niacin, mg |

40 |

40 |

Meanwhile the patient suffered severe weight loss (13.8% of initial body weight) during hospital stay. After considering the weight loss incurred by stillbirths, the weight loss was 7.1% when compared to the weight before pregnancy. Accurate estimation of body weight has been obscured by severe edema. Significant weight loss could be confirmed only after the edema has subsided. Medical team and NST should take into consideration that severe edema can obscure accurate body weight measurement. In this patient, sufficient TPN supply was impossible in the early stage due to the presence of severe edema and liver failure. When clinical symptoms started to improve, the patient should have been given ample amount of nutrition to replenish early deficit. But our team failed to do so in this case. The patient experienced severe weight loss despite of substantial EN from day 15. This indicates the necessity of intense nutrition intervention including oral nutrition supplement during oral feeding period.

In conclusion, in difficult situations where the patient was suffering from increased nutrition demand after surgery and insufficient TPN supply in early stage, monitoring and intervention of NST can improve the symptoms and assist swift recovery of the patient. In line with proper treatment of the medical team, continuous nutrition care of NST led to the significant improvements in clinical indices of disease and nutritional status. For the management of critically ill patients, accurate requirement estimation of macronutrients but also micronutrients is important. Additionally dose of nutrients and timing of nutrition intervention is critical. Therefore, inquisitive monitoring of patient followed by elaborate nutrition care of NST team is essential for the excellent clinical outcome.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download