Abstract

This study aimed to provide supporting data for the management of dietary habits in depression by comparing health and nutrition in adult Korean women according to depression status. A total of 2,236 women aged between 19 and 64 years who participated in the 2013 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey were divided into a depression group (n = 315) and a non-depression group (n = 1,921). Among 19–29-year-old women, the depression group showed higher proportions of individuals with impairment of everyday activities, menopause, and suicidal thoughts than the non-depression group. The depression group showed lower intake of cereal, chocolate, meat, and carbonated drinks, as well as a lower index of nutritional quality (INQ) for protein, iron, and niacin. Among 30–49-year-old women, the depression group showed higher proportions of individuals with impairment of everyday activities, chronic disease, stress, and suicidal thoughts. The depression group showed lower intake of rice with mixed grains and higher intake of instant and cup noodles than the non-depression group. Among 50–64-year-old women, the depression group showed higher proportions of individuals with impairment of everyday activities, menopause, stress, and suicidal thoughts. The depression group showed lower intake of vegetables, mushrooms, and seaweed, lower nutritional intake of fat, saturated fat, and n-3 fatty acids, as well as a lower INQ for niacin and a lower Recommended Food Score. For all age groups, individuals with depression showed poorer health and nutritional intake than healthy individuals, demonstrating a correlation of depression with health and nutritional intake.

Depression occurs throughout modern society, differs between individuals, and displays a complex pattern of physical, genetic, and socioeconomic factors [1,2,3]. Depression presents with emotional symptoms such as sadness, frustration, emptiness, despair, guilt, and lethargy, as well as with motivational symptoms, such as loss of interest, loss of appetite, and apathy. The disease can also be associated with behavioral issues such as a decline in interpersonal relations and social life, indecisiveness, and procrastination, and with cognitive symptoms such as impaired memory, judgment, and thinking, attention difficulties, and impaired task performance; in extreme cases, it can even lead to suicide [4].

In a 2013 analysis of depression by the Health Insurance Review Agency (HIRA), using assessment data for health insurance and medical aid from 2009 to 2013, the number of patients receiving treatment increased by approximately 109,000 (19.6%) over 5 years, with an average annual increase of 4.6%, while the total treatment costs increased by 57.9 billion KRW (27.1%), equivalent to an average annual increase of 6.2%. In terms of sex, the annual number of female patients receiving treatment was approximately 2.2-fold higher than the number of male patients [5]. The prevalence of depression in Korean adults is 10.2%, but the rate is 6.6% for men and 13.7% for women, meaning that depression is approximately twice as common in women [6]. Reasons for the higher prevalence of depression in women include cyclic hormonal changes related to menstruation, childbirth, and menopause, in addition to the dual burden of marriage and child-rearing, abuse, low social achievement, genetic factors, and the characteristics of the female gender role [1]. Based on data from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from 2005–2008, the prevalence of depressive symptoms in adults was 22%, and 0.6% of these were reported to have severe depression [7]. Depression is a chronic, recurring disease that affects more women than men, and approximately 20% of women in the United States experience depression at some point in their lives [8]. By 2020, depression is predicted to be the second most prevalent disease worldwide, after cardiac disease [9].

The severity of depression differs with health, with better health associated with lower severity of depression [10]. Depressed women have more health problems and physical symptoms than women who are not depressed, and depressive tendencies are associated with a more negative perception of one's own health [11]. Moreover, a study found that a group of individuals with experience of disease within the last year had a higher severity of depression than the group with no disease in the last year [12].

Depression can be related to nutritional deficiencies, and dietary factors have been reported as risk factors for depression and cognitive impairment [13,14]. Depression can be relieved through consumption of a natural, vegan diet with plenty of brown rice, mixed grains, whole grains, beans, raw vegetables, fruit, seeds, and nuts [15]. In addition, depressive symptoms were reported to improve when processed foods and caffeinecontaining foods were restricted for three weeks in depressed patients [16]. In a study from Europe, high consumption of fish was associated with a lower risk of depression, but this association was not present for Asia, North America, South America, or Oceania [17]. Meanwhile, among the psychological functions of carbohydrates, fatty acids, cholesterol, and folic acid, effects on depression have been reported, in particular [18,19,20,21], and good quality proteins, vitamins, and minerals have been reported to have a protective effect against depression [22,23]. Depression could be also relieved through the consumption of sufficient vitamin B1, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, niacin, pantothenic acid, biotin, choline, calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, potassium, sodium, iodine, and copper, which are nutrients that participate in neural and mental activity [15].

As reflected by the above studies, there have been a large number of studies on dietary habits and dietary factors in depression. Nevertheless, there is still a significant lack of research regarding the correlations of depression with health and nutrition in adult Korean women. Therefore, the current study used data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES), which is able to reflect the characteristics of adult Korean women, to examine two hypotheses: first, that depressed individuals would show poorer physical and mental health than non-depressed individuals; second, that depressed individuals would show poorer nutritional intake than non-depressed individuals. By comparing health and nutritional intake according to the presence or absence of depression for adult Korean women of different age groups, this study aimed to provide supporting data to assist in dietary management in depression.

This study used data from the first year of the KNHANES VI (2013), which was performed by the Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [24]. A total of 8,018 subjects participated in at least one survey out of the health survey, the medical examination, and the nutrition survey, and of these, 2,666 were adult women aged 19–64 years. Among these, 26 pregnant women, 43 breastfeeding women, six women who did not respond to the diet questionnaire, and 112 women currently undergoing dietary therapy for medical purposes were excluded, leaving a total of 2,479 subjects initially included in the study. We used KNHANES database available to the public and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the KCDC.

The criteria for dividing the subjects into the depression group and the non-depression group were as follows: from among the 50 people who responded "Yes" to the question of "Do you currently have depression?" on the health questionnaire and the 293 people who responded "Yes" to the question of "Have you felt such sadness or despair that it impaired your daily activities for at least two weeks in the last year?" the 315 subjects (12.7%) who responded "Yes" to both questions were included in the depression group. Excluding these subjects and the 243 subjects (9.8%) who did not respond to the above questions, the remaining 1,921 subjects (77.5%) were classified as the non-depression group, meaning that there were a total of 2,236 subjects in the two groups combined. Subjects were divided into age groups of 19–29 years, 30–49 years, and 50–64 years, in accordance with the Korea Nutrition Society's Dietary Reference Intakes for Koreans [25]. The depression group included 45 subjects (14.3%) aged 19–29 years, 119 subjects (37.8%) aged 30–49 years, and 151 subjects (47.9%) aged 50–64 years, while the non-depression group included 322 subjects (16.8%) aged 19–29 years, 958 subjects (49.9%) aged 30–49 years, and 641 subjects (33.4%) aged 50–64 years.

In terms of general characteristics, height, weight, waist circumference, and body mass index (BMI) were obtained from the health examination survey, and sex, age, education level, annual frequency of alcohol consumption, current smoking status, and moderate physical activity were obtained from the health survey. For waist circumference cutoff values, 85 cm and 90 cm were used for women and men, respectively, in accordance with the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity (KOSSO) criteria for abdominal obesity [6,26].

Obesity status was obtained from the health examination survey, and body weight control in the last year was obtained from the health survey. Obesity status was classified into "Underweight", "Normal", and "Obese", where BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 is underweight, 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 is normal, and ≥ 25 kg/m2 is obese [6,26].

Within the nutrition survey, this study used the average intake frequency and the average intake per serving in the last year for 112 types of food from the food intake frequency survey. Daily intake frequency was calculated using the median of intake frequency responses, and intake per serving was converted to a ratio relative to the recommended daily intake amounts. Finally, daily intake frequency and intake per serving were used to obtain the servings/day.

The 112 food items were reclassified into the following 29 categories: white rice, rice and mixed grains, other rice, noodles, instant noodles/cup noodles, rice cakes, bread, pizza/hamburger/sandwich, cereal, snacks, chocolate, starchy root vegetables, sugars, beans, nuts, vegetables/mushrooms/seaweed, kimchi, fruit, meat, processed meat, eggs, fish and shellfish, processed fish and shellfish, milk and dairy, oils, coffee, carbonated drinks, tea, and alcohol.

Daily food intake data had been collected by the 24-hour dietary recall method. Average daily nutrient intake was obtained for the 21 nutrients.

The food intake data used were collected by the 24-hour dietary recall method, as part of the nutrition survey. The INQ is an index that has been corrected for energy intake and evaluates whether an individual is consuming the recommended amount of individual nutrients. It is represented by the ratio of nutrient intake per 1,000 kcal to recommended nutrient intake per 1,000 kcal. Hence, for meals with an INQ greater than 1.0 for a particular nutrient, intake of this nutrient is high relative to energy intake, and so, the quality of that meal is considered high. Meanwhile, if a meal has an INQ of less than 1.0, this means that the nutrient intake is low relative to energy intake and so the quality of that meal is considered to be low [27]. As with the nutrient adequacy ratio (NAR), this was calculated for nine nutrients.

INQ = nutrient intake per 1,000 kcal / recommended nutrient intake per 1,000 kcal

The daily number of meals and the average intake frequency over the last year for 112 types of food were obtained from the food intake frequency survey, as part of the nutrition survey. The RFS is a method for evaluating the quality of meals, developed by Kant et al. [28] Based on the weekly intake frequency of healthy foods such as mixed grains, fruit, vegetables, lean meat, and low-fat dairy products, 1 point is given for foods consumed at least once per week, and 0 points are given for foods consumed less than once per week. In South Korea, Kim et al. [29] calculated the RFS using Korean foods to suit the domestic dietary environment, using categories of grains, beans, vegetables, seaweed, fruits, seafood, dairy, and nuts [30]. In the current study, the method of Kim et al. [29,30] was used with a few changes.

In this study, a total of 43 items were analyzed: the daily number of meals eaten, plus 42 types of food. One point was given if all three meals were eaten each day, and for the remaining food categories, 1 point was given if the intake frequency was at least once per week, and 0 points were given if the intake frequency was less than once per week, meaning that the maximum possible score was 43 points. Food categories were classified as grains (1 item), beans (6), vegetables (10), seaweed (4), fruits (11), seafood (6), dairy (3), and nuts (1).

SAS program (version 9.3, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for statistical analysis of all data, applying the proc survey procedure such as proc surveyreg. Data analysis for the KNHANES utilized stratification variables and cluster variables.

The t-test and Chi-square test were used to analyze differences in general characteristics, social characteristics, obesity, body weight control, health, and mental health according to depression status, as well as for the comparative analysis of nutrition intake assessment according to nutrient intake and food intake. The statistical significance level was p < 0.05.

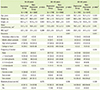

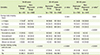

Table 1 displays the general characteristics for the depression group and the non-depression group in this study. The average ages in the depression group and the non-depression group, respectively, were 23.6 ± 0.5 and 24.1 ± 0.2 years for the 19–29 age group, 40.9 ± 0.6 and 39.6 ± 0.2 years for the 30–49 age group, and 56.7 ± 0.4 and 56.4 ± 0.2 years for the 50–64 age group. Body weight, height, and BMI were lower for the depression group than the non-depression group in the 50–64 age group (p < 0.0004, p < 0.009, p < 0.007), and waist circumference was significantly higher for the depression group in the 30–49 age group (p < 0.045). In terms of education, the proportion of middle school graduates or lower in the 30–49 and 50–64 age groups (p < 0.001, p < 0.001) was higher for the depression group, while the proportion of college graduates or higher was significantly higher in the non-depression group. In terms of alcohol consumption, the depression group featured a higher number of individuals in the 30–49 and 50–64 age groups (p < 0.0001, p < 0.010) who drank at least four times per week, while the proportion of non-drinkers in the non-depression group was significantly higher. In terms of smoking, the proportion of current smokers was higher in the depression group for the 19–29, 30–49, and 50–64 age groups (p = 0.002, p = 0.0002, p = 0.012), while the proportion of never smokers was significantly lower in the depression group.

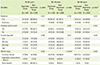

Table 2 displays the social characteristics for the depression group and the non-depression group in this study. The proportion of subjects living in rural areas was higher in the depression group for the 19–29 and 50–64 age groups (p = 0.007, p = 0.033). In terms of economic activity, the proportion of unemployed and economically inactive subjects was significantly higher in the depression group for the 19–29 age group (p = 0.003). The depression group showed a higher proportion of low income than the non-depression group in the 30–49 age group (p = 0.003), while the proportion of upper middle and high income was significantly lower in the depression group. In terms of marital status, the depression group showed a significantly higher proportion of separated/bereaved/divorced subjects in the 30–49 and 50–64 age groups (p < 0.0001, p = 0.050).

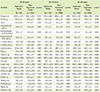

Table 3 displays the results for obesity and body weight control in the depression group and the non-depression group in this study. The depression group showed a lower proportion of underweight and obese subjects than the non-depression group in the 50–64 age group (p = 0.017), and showed a higher proportion of subjects with normal BMI. The proportion of subjects who had attempted to lose weight or gain weight in the last year was higher in the depression group for the 30–49 age group (p = 0.001), while the proportion of subjects who had attempted to maintain their weight or who had never attempted body weight control was lower in the depression group. The depression group showed a lower proportion of subjects who had attempted to lose weight, maintain body weight, or had never attempted body weight control for the 50–64 age group (p = 0.043), while the proportion of subjects who had attempted to gain weight was significantly higher for the depression group than the non-depression group.

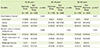

Table 4 displays the current state of health for the depression group and the non-depression group in this study. The proportion of subjects with impairment of daily activities was significantly higher in the depression group for the 19–29, 30–49, and 50–64 age groups (p = 0.0004, p < 0.0001, p < 0.0001), while the proportion of subjects with "bad" or "very bad" subjective health was significantly higher in the depression group for the 30–49 and 50–64 age groups (p < 0.0001, p < 0.001). The proportion of subjects who had undergone menopause was significantly higher for the depression group in the 19–29 and 50–64 age groups (p = 0.030, p = 0.027), while the depression group also showed a significantly higher proportion of subjects in the 30–49 age group (p = 0.0003) who currently had at least one chronic disease.

Table 5 displays the mental health results for the depression group and the non-depression group in this study. In terms of perceived stress, the depression group showed a significantly higher proportion of subjects reporting "a lot of stress" or "quite a lot of stress" for the 30–49 and 50–64 age groups (p < 0.0001, p < 0.0001). The proportion of subjects who reported suicidal thoughts within the last year was significantly higher in the depression group than the non-depression group for the 19–29, 30–49, and 50–64 age groups (p < 0.0001, p < 0.0001, p < 0.0001).

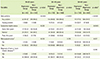

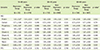

Table 6 shows the food intake amounts for the depression group and the non-depression group in this study. For the 19–29 age group, the depression group showed significantly lower intake of cereal (p = 0.008), chocolate (p = 0.029), meat (p = 0.048), and carbonated drinks (p = 0.022). For the 30–49 age group, the depression group showed significantly lower intake (in servings/day) of rice with mixed grains (p = 0.002), and significantly higher intake of instant noodles and cup noodles (p = 0.004). For the 50–64 age group, the depression group showed significantly lower intake of vegetables, mushrooms, and seaweed (p = 0.045).

Table 7 shows the nutrient intake for the depression group and the non-depression group in this study. Compared to the non-depression group, the depression group showed significantly lower intake of fat (p = 0.045), saturated fat (p = 0.013), and n-3 fatty acids (p = 0.033) for the 50–64 age group.

Table 8 displays the INQ and RFS for the depression group and the non-depression group in this study. In the 19–29 age group, the INQ for protein was significantly lower in the depression group than the non-depression group (p = 0.017), but since it was higher than 1.0, there was no problem with the quality of meals. Similarly, the INQ for iron was significantly lower in the depression group for the 19–29 age group (p = 0.038), but the value was higher than 1.0, and so there was no problem with the quality of meals. The INQ for niacin was significant lower in the depression group for the 19–29 and 50–64 age groups (p = 0.003, p = 0.045), but there were no problems with meals for either of these groups. The INQ for calcium was below 1.0 in both the depression and the non-depression group for all age groups, and the INQ for vitamin C was below 1.0 in both the depression and the non-depression group for the 19–29 age group, indicating a low quality of meals for these two nutrients. In the 50–64 age group, the RFS of 13.75 ± 0.63 for the depression group was significantly lower than the score of 15.23 ± 0.39 for the non-depression group (p < 0.045).

The current study aimed to investigate the association of depression with health and dietary habits in different age groups of adult Korean women, by comparing health and nutrition intake in a depression group and a non-depression group.

In the 50–64 age group, the proportion of underweight and obese subjects was lower in the depression group than in the non-depression group, while the proportion of individuals with normal BMI was significantly higher. A study of 50–89-year-old women in the United States reported that there was no correlation between obesity and the risk of depression [31]. However, in a study of targets for adult disease screening, obese women with a BMI of at least 27 kg/m2 were reported to have strong depressive tendencies [32], and there have been several recent studies supporting a positive correlation between depression and obesity [33]. Therefore, it is thought that the relationship between depression and obesity will require additional study in the future.

The proportion of subjects with impairment of daily activities was significantly higher in the depression group for all age groups. One previous study of adult women with disability reported an association between depression and disability grade, multiple disabilities, and health status [34], while an analysis of the pathway between physical function and depression in patients in a geriatric ward in Pittsburgh, in the US, reported an effect of physical function on depression. Higher rates of depression have been reported in patients with overall restriction of activity, as well as restricted activity due to cardiac disease, stroke, hypertension, fracture or joint injury, arthritis or rheumatism, respiratory disease, visual disability, or disability of the neck [35]. These results are broadly consistent with the results of our study.

For the 30–49 and 50–64 age groups, subjective health was worse in the women in the depression group than in the women in the non-depression group. A previous study in middle-aged women also reported that better health was associated with milder depression severity, and that severity of depression increased with poorer self-perception of physical condition [36]. Another study on the relationship between depression and subjective health perception reported that milder depression sensitivity was associated with better self-perception of health [37].

For the 19–29 and 50–64 age groups, the depression group showed a significantly higher proportion of subjects who had experienced menopause. In a previous study, a group of individuals who had experienced menopause showed a higher severity of depression [38], while a study investigating intermediary variables between menopause and depression in 45–54-year-old Turkish women reported that sleeping difficulties and changes in memory, as symptoms of menopause, were significant predictive factors of depression [39]. Although the age of menopause varies among countries, the average age of menopause for women in developed countries is generally 52 years, while the average age in Korean women is 49.3 years, in Turkish women it is 45.8 years, and in Mexican women it is 48 years [40,41,42].

For the 30–49 age group in the present study, the proportion of subjects currently diagnosed with at least one chronic disease was significantly higher in the depression group than in the nondepression group. This is consistent with other results, such as the findings of a study of 40-year-old adults that women with an existing disease were more likely to experience depressed moods [43], and a study reporting a higher rate of depression in a group with hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction, or angina compared to the group without any of these diseases [35]. The vascular depression hypothesis is based on the idea that vascular diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and cardiac disease cause cerebral small vessel disease in subcortical regions of the brain, and that this, in turn, causes depression through the impairment of neurobiological function [44]. Conversely, there are also reports that the excessive secretion of adrenocortical hormones in depression causes accumulation of fat, abdominal obesity, diabetes, and hypertension [45].

Perceived everyday stress was significantly higher in the depression group for the 30–49 and 50–64 age groups. In one study of factors affecting depression in menopausal women, stress had the most explanatory power at 53%, compared to 3% for menopausal symptoms, 2% for marriage adaptation, and 1% for health promoting behaviors [38].

In terms of suicidal thoughts in the last year, the depression group showed a significantly higher proportion of subjects with suicidal thoughts compared to the non-depression group, for all age groups. Similarly, a study of female dental hygiene students showed that higher levels of depression were associated with more frequent thoughts about death, experience of suicidal impulses, and suicide attempts [46]. A study in rural areas in Iowa, in the US, also reported that suicidal thoughts were most common in middle-aged individuals of 45–64 years, and showed a strong association with depression [47].

In terms of food intake, for the 19–29 age group, the depression group showed a lower intake of cereal, chocolate, meat, and carbonated drinks compared to the non-depression group. For the 30–49 age group, the depression group showed a lower intake of rice with mixed grains, and a higher intake of instant noodles and cup noodles. For the 50–64 age group, the depression group showed a significantly lower intake of vegetables, mushrooms, and seaweed.

In a previous study, high intake of fruits, vegetables, and fish was reported to protect against depressive symptoms in 19–29-year-old women, while processed meats, chocolate, sweet desserts, fried food, refined grains, and high-fat dairy products were reported to increase vulnerability to depressive symptoms [48]. The diet used for depression in a study from the United Kingdom consisted of reducing sugar and stimulants such as caffeinated drinks and nicotine, increasing fruit and vegetable intake to five servings/day, consuming oily fish such as mackerel, tuna, salmon, or herring at least twice a week, and consuming plenty of protein from fish, meat, eggs, beans, and pulses [49].

For 30–49-year-old women, a prospective cohort study in the United Kingdom showed that high scores for depression were associated with a high intake of sweet desserts, fried food, processed meat, refined grains, and high-fat dairy products [50], while a higher prevalence of psychiatric symptoms was reported in subjects with deficiency of folic acid from fruit, vegetables, beans, and seaweed [51]. A study from Spain also reported that fast food could increase the risk of depression [52]. However, a study of the 20–39-year-old subjects who participated in the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in 1999–2000 and 2001–2002 did not discover a significant association between depression and consumption of fish or seafood [53].

For 50–64-year-old women, one study of middle-aged adults in the United Kingdom reported a negative correlation between depressive symptoms and meals consisting of natural foods, including large amounts of vegetables, fruit, and fish, while the authors also reported a positive correlation with processed foods, including large amounts of processed meat, fried food, refined grains, and sweet desserts [50]. Another study from China reported a relationship between depression and intake of fish, and high intake of fish was reported to reduce the risk of depression in Europe, but was reported to show no correlation in Asia, North America, South America, or Oceania [54].

In terms of nutrient intake, the 50–64 age group showed a significantly lower intake of fat, saturated fat, and n-3 fatty acids in the depression group compared to the non-depression group. A study of female college students in Spain reported that low intake of n-3 fatty acids was related to depression [55]. N-3 fatty acids (omega-3 fatty acids), eicosapentanoic acid, and docosahexanoic acid are specific polyunsaturated fatty acids that are found in high concentrations in the brain and the phospholipid membranes of nerve cells [56], and a lack of n-3 fatty acids can lead to changes in plasma membrane microviscosity that can alter the neurotransmitter systems and progress to mood disorders [57]. A study from France reported that Eskimos consume up to 16 g of fish oil per day, and that this high intake of n-3 fatty acids promotes production of the neurotransmitter dopamine over the long-term, causing the emotional centers of the brain to produce a pleasant mood and improving the efficacy of treatment for depression [58]. In a study from the United States, a high ratio of n-6 fatty acids to n-3 fatty acids in the diet was reported to contribute to an increased incidence of depression and worsening severity of depression [59]. However, in a case-control study from Japan, depression was not associated with any difference in consumption frequency of fish or polyunsaturated fatty acids [60].

For the 19–29 age group, the INQs for protein, iron, and niacin were lower in the depression group than in the non-depression group, while for the 50–64 age group, the INQ of niacin was significantly lower in the depression group. In a previous study of adult women, the INQs for protein, phosphorus, calcium, vitamin A, vitamin B1, and vitamin B2 were lower in the depression group than in the non-depression group, while the INQs for calcium and vitamin B2 were below 0.75 in both groups, indicating a poor quality of meals for these nutrients [13,61].

The RFS is a method of assessing the quality of meals based on the weekly frequency of consumption of healthy foods, such as mixed grains, fruit, vegetables, lean meat, and low-fat dairy products. For the 50–64 age group, the depression group showed a significantly lower RFS than the non-depression group, and a high RFS was associated with less depression. A study of adults in Japan found that a healthy Japanese diet, characterized by high intake of vegetables, fruit, tofu, and mushrooms, was associated with a reduced prevalence of depressive symptoms [62].

This study had several limitations: first, since the KNHANES was a cross-sectional study, it is unable to elucidate causation for the factors that affect depression. Second, nutrient intake was calculated as daily intake based on the 24-hour dietary recall method, but this does not provide a perfect estimate of everyday intake. Nevertheless, by using data from the food consumption frequency survey, consisting of 112 foods commonly eaten by Koreans, it was possible to examine the relationship between intake of each food and depression. In spite of its limitations, this study can be considered important insofar as it has investigated various factors related to depression within sociodemographic characteristics, health, and nutrition for different age groups of adult women in South Korea.

In terms of sociodemographic characteristics, South Korean women with depression were more likely to drink and smoke, were more likely to live in an rural area, were more likely to be unemployed or economically inactive, and were more likely to be separated, bereaved, or divorced, while they showed lower education levels and incomes. For all age groups studied, women with depression showed poorer health than healthy subjects, and the 30–49 and 50–64 age groups, in particular, demonstrated significant differences for many variables. Depressed subjects also showed poorer nutrition than healthy subjects for all age groups. Therefore, in adult Korean women of different ages, health and nutrition were found to be related to depression, while this association was increased for older age groups.

Nutritional deficiencies that result from depression can be important factors that worsen mental health and can cause other diseases. Therefore, together with efforts to improve health and diet, various psychological factors also need to be considered when planning and implementing a nutrition plan to manage dietary habits in individuals with depression. In the future, we think it will be necessary to continue performing research into various factors that can provide directions for dietary management in depression for adult women of different age groups. Prospective and clinical studies should be favored over crosssectional studies.

Figures and Tables

Table 1

General characteristics between depression group and non-depression group

BMI: body mass index.

*p-values for continuous variables by t-test, for categorical variables by Chi-square test; †Mean ± SD (standard deviation); ‡Waist circumference criteria: ≥ 85 cm (women), ≥ 90 cm (men): Korean Society for the Study of Obesity; §n (%); llModerate physical activity: ≥ half-hour/1 time, ≥ 5 days/week.

Table 2

Socioeconomic characteristics between depression group and non-depression group

Table 3

Obesity status and weight control attempt between depression group and non-depression group

Table 4

Physical health status between depression group and non-depression group

Table 5

Mental health status between depression group and non-depression group

Table 6

Food groups intake between depression group and non-depression group

Table 7

Mean daily nutrient intake between depression group and non-depression group

Table 8

INQ and RFS between depression group and non-depression group

References

1. Sung KS. Study on relationships between depression and the quality of life (EQ-5D): centered on the subjects of 『Survey on national health and nutrition the fourth period the first year(2007)』 [master's thesis]. Seoul: Yonsei University;2009.

2. Choi MK, Lee YH. Depression, powerlessness, social support, and socioeconomic status in middle aged community residents. J Korean Acad Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2010; 19:196–204.

3. Hong KW. Korean depression genetics studies. Public Health Wkly Rep. 2012; 5:342–345.

4. Kwon SM. Relationship between depression and anxiety: Their commonness and difference in related life events and cognitions. Psychol Sci. 1996; 5:13–38.

5. Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service (KR). Total medical expenses status and care personal by gender's depression [Internet]. 2014. cited 2015 March 15. Available from http://www.hira.or.kr/co/search.do?collection=ALL&query=%EC%9A%B0%EC%9A%B8&x=0&y=0.

6. Ministry of Health and Welfare. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Korea Health Statistics 2013: Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES VI-1). Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2014.

7. Shim RS, Baltrus P, Ye J, Rust G. Prevalence, treatment, and control of depressive symptoms in the United States: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 2005-2008. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011; 24:33–38.

8. Lucas M, Chocano-Bedoya P, Shulze MB, Mirzaei F, O'Reilly EJ, Okereke OI, Hu FB, Willett WC, Ascherio A. Inflammatory dietary pattern and risk of depression among women. Brain Behav Immun. 2014; 36:46–53.

9. World Health Organization. Burden of mental and behavioral disorder. The world health report 2001-mental health: new understanding, new hope. Geneva: World Health Organization;2001. p. 19–46.

10. Kim HY, Koh HJ. Study on depression and ego identity of middle-aged women. J Korean Acad Womens Health Nurs. 1997; 3:117–138.

11. Woods NF, Mitchell ES. Pathways to depressed mood for midlife women: observations from the Seattle Midlife Women's Health Study. Res Nurs Health. 1997; 20:119–129.

12. Kim JY. A study of the relationship between self concept and depression of middle-aged women. J Korean Acad Womens Health Nurs. 1997; 3:103–116.

13. Lee JW. A comparative study on eating habits and nutrients intake of depressed and normal subjects: base on 2008 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [master's thesis]. Daejeon: Chungnam National University;2009.

14. Rogers PJ. A healthy body, a healthy mind: long-term impact of diet on mood and cognitive function. Proc Nutr Soc. 2001; 60:135–143.

15. Song SJ, Kim MS. Case study on insomniac, melancholiac, schizophrenic patients taking well-balanced nutrition & vitamin B group. J Korean Soc Jungshin Sci. 2002; 6:11–28.

16. Christensen L. Psychological distress and diet: effects of sucrose and caffeine. J Appl Nutr. 1988; 40:44–50.

17. Li F, Liu X, Zhang D. Fish consumption and risk of depression: a meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016; 70:299–304.

18. Wurtman RJ, Hefti F, Melamed E. Precursor control of neurotransmitter synthesis. Pharmacol Rev. 1980; 32:315–335.

19. Bruinsma KA, Taren DL. Dieting, essential fatty acid intake, and depression. Nutr Rev. 2000; 58:98–108.

20. Young SN. The use of diet and dietary components in the study of factors controlling affect in humans: a review. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 1993; 18:235–244.

21. Yim YH. The effect of calcium supplementation and supplementary duration with depression at Korean home-maker [master's thesis]. Busan: Dong-A University;2004.

22. Kim JM, Stewart R, Kim SW, Yang SJ, Shin IS, Yoon JS. Predictive value of folate, vitamin B12 and homocysteine levels in late-life depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2008; 192:268–274.

23. Skarupski KA, Tangney C, Li H, Ouyang B, Evans DA, Morris MC. Longitudinal association of vitamin B-6, folate, and vitamin B-12 with depressive symptoms among older adults over time. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010; 92:330–335.

24. Ministry of Health and Welfare. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Korea Health Statistics 2013: Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES VI-1). Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2014.

25. The Korean Nutrition Society. Dietary referece intakes for Koreans. 1st rev. ed. Seoul: The Korean Nutrition Society;2010.

26. Korean Society for the Study of Obesity. Obesity treatment guidelines: 2012. Seoul: Korean Society for the Study of Obesity;2012.

27. Oh SY. Analysis of method on dietary quality assessment. Korean J Community Nutr. 2000; 5:362–367.

28. Kant AK, Schatzkin A, Graubard BI, Schairer C. A prospective study of diet quality and mortality in women. JAMA. 2000; 283:2109–2115.

29. Kim JY, Yang YJ, Yang YK, Oh SY, Hong YC, Lee EK, Kwon O. Diet quality scores and oxidative stress in Korean adults. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011; 65:1271–1278.

30. Yang YJ. Mild cognitive impairment and nutrition in old adults. Hanyang Med Rev. 2014; 34:53–59.

31. Palinkas LA, Wingard DL, Barrett-Connor E. Depressive symptoms in overweight and obese older adults: a test of the "jolly fat" hypothesis. J Psychosom Res. 1996; 40:59–66.

32. Lee JH, Kim GH, Kim JW. Differences in depression, anxiety, self-esteem according to the degree of obesity in women: a pilot study. J Orient Neuropsychiatry. 2002; 13:93–100.

33. Onyike CU, Crum RM, Lee HB, Lyketsos CG, Eaton WW. Is obesity associated with major depression? Results from the third national health and nutrition examination survey. Am J Epidemiol. 2003; 158:1139–1147.

34. Kwon BS, Park HS. A study of the actual conditions and influencing factors on depression of female adults with disabilities. Korean J Soc Welf. 2005; 57:169–192.

35. Kim JM, Lee JA. Depression and health status in the elderly. J Korean Gerontol Soc. 2010; 30:1311–1327.

36. Jun SJ, Kim HK, Lee SM, Kim SA. Factors influencing middle-aged women's depression. J Korean Community Nurs. 2004; 15:266–276.

37. Kang HS, Kim KJ. The correlation between depression and physical health among the aged. J Korean Public Health Assoc. 2000; 26:451–459.

38. Chang HK, Cha BK. Influencing factors of climacteric women's depression. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2003; 33:972–980.

39. Bosworth HB, Bastian LA, Kuchibhatla MN, Steffens DC, McBride CM, Skinner CS, Rimer BK, Siegler IC. Depressive symptoms, menopausal status, and climacteric symptoms in women at midlife. Psychosom Med. 2001; 63:603–608.

40. Melby MK, Lock M, Kaufert P. Culture and symptom reporting at menopause. Hum Reprod Update. 2005; 11:495–512.

41. Price SL, Storey S, Lake M. Menopause experiences of women in rural areas. J Adv Nurs. 2008; 61:503–511.

42. Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977; 1:385–401.

43. Chu JE, Lee HJ, Yoon CH, Cho HI, Hwang JY, Park YJ. Relationships between depressed mood and life style patterns in Koreans aged 40 years. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr. 2014; 43:772–783.

44. Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, Campbell S, Silbersweig D, Charlson M. 'Vascular depression' hypothesis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997; 54:915–922.

45. Vogelzangs N, Penninx BW. Depressive symptoms, cortisol, visceral fat and metabolic syndrome. Tijdschr Psychiatr. 2011; 53:613–620.

46. Han SY, Jung UJ, Cheon SY. A study on the degree of depression and death orientation of some students majoring in dental hygiene. J Dent Hyg Sci. 2013; 13:230–237.

47. Turvey C, Stromquist A, Kelly K, Zwerling C, Merchant J. Financial loss and suicidal ideation in a rural community sample. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002; 106:373–380.

48. Akbaraly TN, Brunner EJ, Ferrie JE, Marmot MG, Kivimaki M, Singh-Manoux A. Dietary pattern and depressive symptoms in middle age. Br J Psychiatry. 2009; 195:408–413.

49. Holford P. Depression: the nutrition connection. Prim Care Ment Health. 2003; 1:9–16.

50. Akbaraly TN, Brunner EJ, Ferrie JE, Marmot MG, Kivimaki M, Singh-Manoux A. Dietary pattern and depressive symptoms in middle age. Br J Psychiatry. 2009; 195:408–413.

51. Fava M, Borus JS, Alpert JE, Nierenberg AA, Rosenbaum JF, Bottiglieri T. Folate, vitamin B12, and homocysteine in major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1997; 154:426–428.

52. Sánchez-Villegas A, Toledo E, de Irala J, Ruiz-Canela M, Pla-Vidal J, Martínez-González MA. Fast-food and commercial baked goods consumption and the risk of depression. Public Health Nutr. 2012; 15:424–432.

53. Mora K. Diet and depression: a secondary analysis from NHANES 1999-2002 [doctor's thesis]. Tucson (AZ): The University of Arizona;2006.

54. Li F, Liu X, Zhang D. Fish consumption and risk of depression: a meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016; 70:299–304.

55. Sánchez-Villegas A, Henríquez P, Bes-Rastrollo M, Doreste J. Mediter-ranean diet and depression. Public Health Nutr. 2006; 9:1104–1109.

57. Maidment ID. Are fish oils an effective therapy in mental illness--an analysis of the data. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000; 102:3–11.

58. Chalon S, Delion-Vancassel S, Belzung C, Guilloteau D, Leguisquet AM, Besnard JC, Durand G. Dietary fish oil affects monoaminergic neurotransmission and behavior in rats. J Nutr. 1998; 128:2512–2519.

59. Bruinsma KA, Taren DL. Dieting, essential fatty acid intake, and depression. Nutr Rev. 2000; 58:98–108.

60. Su KP, Huang SY, Chiu CC, Shen WW. Omega-3 fatty acids in major depressive disorder. A preliminary double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003; 13:267–271.

61. Park KS, Lee KA. A case study on the effect of Ca intake on depression and anxiety. Korean J Nutr. 2002; 35:45–52.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download