Abstract

Dyslipidemia has significantly contributed to the increase of death and morbidity rates related to cardiovascular diseases. Clinical nutrition service provided by dietitians has been reported to have a positive effect on relief of medical symptoms or reducing the further medical costs. However, there is a lack of researches to identify key competencies and job standard for clinical dietitians to care patients with dyslipidemia. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to analyze the job components of clinical dietitian and develop the standard for professional practice to provide effective nutrition management for dyslipidemia patients. The current status of clinical nutrition therapy for dyslipidemia patients in hospitals with 300 or more beds was studied. After duty tasks and task elements of nutrition care process for dyslipidemia clinical dietitians were developed by developing a curriculum (DACUM) analysis method. The developed job standards were pretested in order to evaluate job performance, difficulty, and job standards. As a result, the job standard included four jobs, 18 tasks, and 53 task elements, and specific job description includes 73 basic services and 26 recommended services. When clinical dietitians managing dyslipidemia patients performed their practice according to this job standard for 30 patients the job performance rate was 68.3%. Therefore, the job standards of clinical dietitians for clinical nutrition service for dyslipidemia patients proposed in this study can be effectively used by hospitals.

Prevalence of chronic illnesses is increasing due to rapid economic development, undesirable lifestyle and diet, and the increase of elderly population [1,2]. Particularly, a cardiovascular disease is one of the top three causes of death around the world and induces significant economic burden [3,4]. In South Korea, prevalence of dyslipidemia is also increasing and contributes to growing of death and morbidity rate in patients with cardiovascular diseases [5,6]. Various factors such as age, physical activity, obesity, heredity and stresses are affecting the d e velopment of dyslipidemia [7] and, especially, a diet is the most influencing factor to dyslipidemia [8]. Hence a certain but official format of dietary guidelines is necessary and become important component in effective management and prevention of dyslipidemia [9]. Korean Society of Lipidology and Atherosclerosis proposed a modified and supplemented dyslipidemia treatment guideline in 2009. The guideline recommends maintaining normal weight; limiting cholesterol intake to 200 mg per day as suggested by national cholesterol education program adult treatment panel III (NCEP-ATP III); limiting saturated fatty acids to 7% of the total energy intake, as the intake of animal lipids is increasing; limiting trans fatty acids less than 1% of the total energy intake recommend by world health organization (WHO); polyunsaturated fatty acid to 10% of the total energy intake, soluble dietary fiber to 10-25 g/d; carbohydrate to 60% of the total energy intake; and alcohol less than two glasses per day [10]. Furthermore, relevant guidelines were announced in USA and European countries and the correlation between dyslipidemia and diet were emphasized in their announcement [11,12].

In South Korea, for systematic and intensified dietary management in clinics and hospitals, the Korean goverment legislated certification system for government certified clinical dietitians in 2010 and began this certification system in 2012 to foster government-certified clinical dietitians who will perform nutrition assessment, nutrition consultation, and nutrition monitoring and evaluation [13]. Professional clinical nutrition service has been reported to have positive effects on reducing length of stay (LOS) and medical costs of patients [14,15,16], and Korean medical staff of the clinical nutrition services for disease management are always in high demands in Korea [17]. In the U.S., joint commission on accreditation of health organization (JCAHO) and academy of nutrition & dietetics (AND, former American dietetic association) participated in developing nutrition care standard for clinical dietitians in planning of diet therapy [18] and AND proposed standards of practice (SOP) and standard of professional performance (SOPP) for clinical dietitians [19,20]. Although Korean hospitals and clinics introduced the concept of nutrition care process (NCP) for standardizing the process of nutrition management by clinical dietitians, actual NCP application cases in the field are very limited so far. Also, even though several researched investigated job characteristics and level of job-satisfactions of dietitians in healthcare centers, schools and hospitals there are no relevant job standard to evaluate job performance or properties of dietitians and the proportion of clinical nutrinutrition tasks in their daily duties is very low [21,22,23,24,25]. Recently, developing a curriculum (DACUM) for defining the job of clinical dietitians at hospitals and standardizing the job based on job description was attempted and devleoped by nutrition experts. However, only a few researches has been conducted regarding job analysis and standardization of tasks for clinical dietitians according to a type of diseases. Therefore, in this study, the job of clinical dietitians who are involved nutrition management of dyslipidemia patients will be analyzed and job standards developed, in order to effectively manage and treat patients with dyslipidemia.

This study was approved by institutional review board (IRB, approval no.: YUHS01-13-003) of Yeungnam university. A survey was conducted on general status of hospital, the number of hospital beds (permitted beds, adjustable beds), clinical dietitian workforce, practice and result of nutrition education and consultation programs, and other questions related to dyslipidemia management by post-mail and email with clinical dietitians at medium and large hospitals with 300 or more beds in Korea from March 2014 to April 2014. Among 239 hospitals, questionnaire was collected from 104 hospitals (39 tertiary hospitals, 59 general hospitals, 6 hospitals), and that was 43.5% answering rate.

In order to develop job standards to standardize the job of clinical nutrition service for dyslipidemia, a DACUM committee was made up of 17 members including clinical dietitians. DACUM is a method to extract task and task elements of clinical dietitians who provide the service to dyslipidemia patients and through this process DACUM creates a relevant job list. The DACUM committee workshop, first, defined the job of clinical dietitians for dyslipidemia and created competency standards based on characteristics of dyslipidemia. The job standard was composed of job elements of basic nutrition care services that clinical dietitian performed and recommended nutrition services specific for dyslipidemia patients. Details of recommended services were added, and, after several meetings, a draft of job standards based on NCP and practice was drawn. Later, the job standards were modified and supplemented based on advice and review of relevant institutes and experts.

For field application evaluation, 10 medical institutions among those with most trainings on dyslipidemia were selected based on the size and region of institution. The survey included job performance, difficulty, and job standard form evaluation, and, for job performance, performance of each task element was studied at each medical institution based on medical records of three cases of clinical nutrition service. Also, task difficulty was recorded based on 'basic service' and 'recommended service' according to practical experience of the subjects, while the job standards form was evaluated by having the subjects write their opinion on changes that need to be made.

All statistical analyses were based on SPSS 21.0 (IBM Corp., NY, USA), and general information of the hospitals was expressed in frequency (percentage) and average ± standard deviation. Education fee and reason for not receiving education fee were examined using multiple responses. ANOVA was used to compare in dyslipidemia nutrition education costs between different types of education. For an inter-group analysis, a post-hoc analysis was performed with Scheffe test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

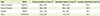

Of the 104 hospitals that participated in this study, 39 (37.5%) were tertiary hospitals, 59 (56.7%) general hospitals, and 6 (5.8%) hospitals. The number of permitted beds was highest in tertiary hospitals, average 985, followed by general hospitals, 599, and hospitals, 393. Also, 69.2% of tertiary hospitals, 56.9% of general hospitals, and 16.7% of hospitals had a separate nutrition education rooms (Table 1).

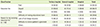

Table 2 shows the reasons why the subject hospitals receive or do not receive dyslipidemia-related education fees. Of the subject hospitals, 66.7% do not receive the dyslipidemiarelated education fee and 48 hospitals of them responded that it was because of 'difficulty of making an education team.'

Table 3 shows the current status of dyslipidemia nutrition education. To the multiple-response question related to the types of dyslipidemia nutrition education, 13.0% responded 'group education', 82.0% 'individual education', 1.0% 'practice', and 4.0% 'group + individual education', and the average education fees were 6,500 KRW for group education, 14,498 KRW for individual education, and 32,625 KRW for group + individual education.

Definition of clinical dietitians for dyslipidemia was made first by the DACUM workshop. And then, after several meetings, clinical dietitians for dyslipidemia were defined as a professional who performs clinical nutrition treatment including self-management education and training to treat dyslipidemia and prevent complications of dyslipidemia for individuals and groups.

The job of clinical dietitians for dyslipidemia patients was analyzed based on the DACUM method, and the job specification included duties, tasks, and task elements. It was composed of 18 tasks and 53 task elements, which were organized in a table (DACUM chart) by duties (Figure 1). Here, the main duties of clinical dietitians were based on core duties defined in previous research [26], and, were in accord with the NCP steps of international confederation of dietetic associations (ICDA), 'A. nutrition assessment', 'B. nutritional diagnosis', 'C. nutrition intervention', and 'D. nutrition monitoring and evaluation.' The duties included specific tasks: for 'A. nutrition assessment,' A1. review basic information, A2. review medical history and treatment plan, A3. evaluate anthropometric data, A4. review laboratory and medical test, A5. review nutrition focused physical findings, A6. collect and evaluate data related to food and nutrition, A7. decide nutritional needs, and A8. document nutrition assessment; for 'B. nutritional diagnosis,' B1. derivate nutritional diagnosis, and B2. document nutritional diagnosis. 'C. nutrition intervention' C1. plan nutrition intervention, C2. management of nutritional prescription, C3. implement of nutrition intervention, C4. document nutrition intervention, and 'D. nutrition monitoring and evaluation,' D1. monitor nutritional status, D2. monitor the nutrition intervention process, D3. evaluate nutrition intervention, and D4. document nutrition monitoring and evaluation.

Based on these job descriptions, a specific job description was added to each task element and the tasks were classified as 'basic' and 'recommended.' 'Basic' means basic tasks that clinical dietitians must perform, whereas 'recommended' means tasks performed by experienced professional dietitians for dyslipidemia.

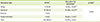

Field application evaluation was performed by working clinical dietitians at 10 medium and large hospitals, and Table 4 shows general information on patients with dyslipidemia to whom the study was applied. Of the 30 patients, 17 were female and 13 male, and the average age was 54.2. Also, 14 were inpatients and 16 outpatients, and 21 received nutrition management only in the beginning while 9 received follow-up management as well. And, the average time for clinical dietitians to provide nutrition management for these patients was 43.8 minutes.

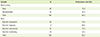

When the job standards were applied to the hospitals, of the 65 basic tasks, 76.9% was performed and, of the 35 recommended services, 52.5% was performed. Also, in terms of duties, 74.4% of the 52 nutrition assessment tasks, 86.0% of the 9 nutritional diagnosis tasks, 75.5% of the 23 nutrition intervention tasks, and 28.2% of the 16 nutrition monitoring and evaluation tasks were performed (Table 5). Table 6 presents the result of studying job performance by duty according to types of dyslipidemia patients. The performance rates of nutrition assessment, nutritional diagnosis, nutrition intervention, and nutrition monitoring and evaluation for inpatients were 67.1%, 69.7%, 76.7%, and 39.2%, respectively, and, for outpatients, 79.4%, 97.2%, 74.7%, and 20.7%.

Table 7 presents the rate of coincidence for task difficulty between the researchers and clinical dietitians. The rates of coincidence for basic tasks, nutrition assessment, nutritional diagnosis, nutrition intervention, and nutrition monitoring and evaluation, were 85.6%, 62.5%, 56.8%, and 63.0%, respectively, while those of recommended services were 46.0%, 66.7%, 55.6%, and 54.0%.

The draft job standards were shown to relevant institutions for advice and review, and, after field application evaluation and discussions, experts mainly suggested that the criteria for 'basic' and 'recommended' tasks need to be more specified; there are too many task elements and items in job description evaluation; and job standards for other diseases were needed as well. Also, the job standards and form developed based on field application evaluation were reviewed by institutions and all respondents were satisfied with the modified job standards. Later, based on field application evaluation and expert advice, the job standards were modified and supplemented, and the final job standards for clinical nutrition treatment of patients with dyslipidemia included 73 basic services and 26 recommended services, among 4 duties, 18 tasks, 53 task elements, and 99 job descriptions (Table 8).

For the purpose of qualitative improvement of clinical nutrition service, in this study, the current status and practice of clinical nutrition service for dyslipidemia in Korean hospitals was studied, and job standards of clinical dietitians for clinical nutrition treatment of patients with dyslipidemia that can be applied to medical institutions were developed based on DACUM analysis and field application evaluation.

For dyslipidemia patients, it has been reported that improving diet through nutrition education and consultation can reduce risk factors and frequency of medication, and improve nutritional knowledge [27]. Therefore, clinical nutrition service provided by clinical dietitians has been reported to maximize treatment efficacy and reduce medical costs [15,28]. Also, clinical nutrition service for prevention and treatment of dyslipidemia is likely to become more important in the future as the prevalence of the disease grows every year. However, unlike in the U.S. where clinical nutrition service is applicable for health insurance benefits since 2002 [29], South Korea does not have no legislative policy relating to clinical dietitians and, therefore, does not insure the service. According to the result of this study, when patients receive nutrition education, individual education costs 24,487 KRW and group education 39,000 KRW. Therefore, if patients can receive insured clinical nutrition service, it may reduce prevalence and death rate of the disease.

Recently, it has been emphasized the tasks of clinical dietitians should be more specific and clear in order to activate services. A series of job activity analyses has been conducted for dietitians at schools, business places, hospitals, and health centers between 2002 and 2008 [23,24,25,30] and, in 2013, job standards of clinical dietitians at hospitals was developed [26] in Korea. This study was conducted based on previous research that suggested a wide range of tasks of clinical dietitians for overall diseases, and analyzed tasks that must be performed by clinical dietitians for clinical nutrition service of dyslipidemia. Here, to determine the tasks in a short period, the DACUM method was used, and the tasks and task elements were proposed according to the four steps of NCP, developed by AND (Academy of nutrition & dietetics, USA). This study may provide a manual for high quality clinical nutrition service by clinical dietitians performing standardized tasks, and to highlight the importance of clinical dietitians at hospitals who are in charge with diet and health management for patients.

The job standards for clinical nutrition treatment of patients with dyslipidemia proposed in this study include 4 duties, 18 tasks, 53 task elements, and 99 job descriptions, with less duties, tasks, and task elements than in the job description of clinical dietitians at hospitals developed by Cha et al. [26], which included 7 duties, 27 tasks, and 93 task elements. The tasks were reduced perhaps because the study was focused on tasks of clinical dietitians for a specific disease rather than overall diseases. Also, AND introduced job standardization for nutritional management since the early 2000s, and has published standard of practice (SOP) and standard of professional performance (SOPP) for clinical dietitians for various diseases [19,20]. While Cha et al. [26] proposed seven duties including nutrition assessment, nutritional diagnosis, nutrition intervention, nutrition monitoring and evaluation, consultation and cooperation, nutrition research, and self-development, this study, based on Korean and overseas studies, proposed four steps according to NCP; nutrition assessment, nutritional diagnosis, nutrition intervention, and nutrition monitoring and evaluation.

When the proposed job standards were applied to hospitals, the performance rate was high, average 68.3%, while the performance rate of nutrition monitoring and evaluation was the lowest, 28.2%. This low performance rate of nutrition monitoring and evaluation, despite the high importance can be explained by a lack of workforce and concentration on evaluation and management of patients. It is believed that inefficient communication with the medical staff in overall hospitals can induce difficulties in clinical nutrition services [31].

Therefore, in this study, job standards for clinical dietitians for dyslipidemia patients at hospitals were developed based on tasks that are most necessary. However, authors believe that there are limitations in applying the proposed job standards to different regions with different medical staff and practices. However, if such limitations are improved and job standards of clinical dietitians are continuously developed, the recognition and status of clinical dietitians will be improved within the hospital and the nation.

The definition and job standards of clinical dietitians for dyslipidemia were made based on DACUM analysis. The job standards included 4 duties, according to the steps defined in NCP, 18 tasks, 53 task elements, and 99 job descriptions, with 73 basic services and 26 recommended services. The job standards for clinical nutrition treatment for patients with dyslipidemia developed in this study can be effectively used in clinical fields and also improve quality of clinical nutrition service and quality of life of patients with dyslipidemia.

Figures and Tables

Table 1

General characteristics of the hospitals surveyed

Table 2

Items related to education fee for dyslipidemia care

Table 3

Nutrition education related to dyslipidemia care

Table 4

Characteristics of the subjects for field application of job standards of clinical dietitian for dyslipidemia care

Table 5

Performance rate of standardized jobs in field application tests

Table 6

Performance rate of standardized jobs in field application tests according to patient type

Table 7

The coincidence rate of perception between the researchers and clinical dietitians on difficulty of standardized jobs in field application tests

Table 8

The job description of clinical dietitian for dyslipidemia care

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from Health Promotion Fund, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea(13-34).

References

1. Song R, June KJ, Ro YJ, Kim CG. Effects of motivation-enhancing program on health behaviors, cardiovascular risk factors, and functional status for institutionalized elderly women. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2001; 31:858–870.

2. Cha JA, Park HR, Lim YS, Lim SH. Developing job description for dietitians working in public health nutrition areas. Korean J Community Nutr. 2008; 13:890–902.

3. Statistics Korea. Causes of death statistics 2013 [Internet]. 2014. cited 2015 March 15. Available from http://www.kostat.go.kr.

4. Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER 3rd, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Pandey DK, Paynter NP, Reeves MJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB. American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Executive summary: heart disease and stroke statistics--2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014; 129:399–410.

5. Kostis JB. The importance of managing hypertension and dyslipidemia to decrease cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2007; 21:297–309.

6. Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Korea Health Statistics 2013: Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES VI-1). Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2014.

7. Haskell WL. Cardiovascular disease prevention and lifestyle interventions: effectiveness and efficacy. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2003; 18:245–255.

8. Kim IS, Seo EA. A long term observation of total cholesterol, blood pressure, BMI and blood glucose concerned with dietary intake. Korean J Community Nutr. 2000; 5:172–184.

10. Korean Society of Lipidology and Atherosclerosis. Guideline for treatment of dyslipidemia. 2nd rev. ed. Seoul: Korean Society of Lipidology and Atherosclerosis;2009.

11. Eckel RH, Jakicic JM, Ard JD, de Jesus JM, Houston Miller N, Hubbard VS, Lee IM, Lichtenstein AH, Loria CM, Millen BE, Nonas CA, Sacks FM, Smith SC Jr, Svetkey LP, Wadden TA, Yanovski SZ, Kendall KA, Morgan LC, Trisolini MG, Velasco G, Wnek J, Anderson JL, Halperin JL, Albert NM, Bozkurt B, Brindis RG, Curtis LH, DeMets D, Hochman JS, Kovacs RJ, Ohman EM, Pressler SJ, Sellke FW, Shen WK, Smith SC Jr, Tomaselli GF. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014; 129:S76–S99.

12. Reiner Ž, Catapano AL, De Backer G, Graham I, Taskinen MR, Wiklund O, Agewall S, Alegría E, Chapman MJ, Durrington P, Erdine S, Halcox J, Hobbs RH, Kjekshus JK, Perrone Filardi P, Riccardi G, Storey RF, David W. Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee of the Spanish Society of Cardiology. ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2011; 64:1168.e1–1168.e60.

13. Korean Institute of Dietetic Education and Evaluation. Clinical dietitian 2015 [Internet]. 2015. cited 2015 March 15. Available from http://www.kidee2011.or.kr/.

14. Pastors JG, Warshaw H, Daly A, Franz M, Kulkarni K. The evidence for the effectiveness of medical nutrition therapy in diabetes management. Diabetes Care. 2002; 25:608–613.

15. Kim HA, Yang IS, Lee HY, Lee YE, Park EC, Nam CM. Evaluation of cost-effectiveness of medical nutrition therapy: meta-analysis. Korean J Nutr. 2003; 36:515–527.

16. Cho Y, Lee M, Jang H, Rha M, Kim J, Park Y, Sohn C. The clinical and cost effectiveness of medical nutrition therapy for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Korean J Nutr. 2008; 41:147–155.

17. Han MH, Lee SM, Lyu ES. Doctors' perception and needs on clinical nutrition services in hospitals. J Korean Diet Assoc. 2012; 18:266–275.

18. Krasker GD, Balogun LB. 1995 JCAHO standards: development and relevance to dietetics practice. J Am Diet Assoc. 1995; 95:240–243.

19. Franz MJ, Boucher JL, Green-Pastors J, Powers MA. Evidence-based nutrition practice guidelines for diabetes and scope and standards of practice. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008; 108:S52–S58.

20. Boucher JL, Evert A, Daly A, Kulkarni K, Rizzotto JA, Burton K, Bradshaw BG;. American Dietetic Association revised standards of practice and standards of professional performance for registered Dietitians (generalist, specialty, and advanced) in diabetes care. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011; 111:156–166.e1-27.

21. Kwon YS. A job analysis in common managemant dietitian of school foodservice: centering around Kyoungsang buk-do. J Korean Diet Assoc. 1999; 5:182–193.

22. Moon HK, Lee AR, Lee YH, Jang YJ. Analysis and framing of Dietitian's Job Description. J Korean Diet Assoc. 2001; 7:87–104.

23. Moon HK, Jang YJ. Analysis of the Dietitian's Job Description in the business and industry foodservice. J Korean Diet Assoc. 2002; 8:121–131.

24. Moon HK, Jang YJ. Analysis of the Dietitian's Job Description in the hospital. J Korean Diet Assoc. 2002; 8:132–142.

25. Moon HK, Jang YJ. Analysis of the Dietitian's Job Description in the school. J Korean Diet Assoc. 2002; 8:143–153.

26. Cha JA, Kim KE, Kim EM, Park MS, Park YK, Baek HJ, Lee SM, Choi SK, Seo JS. Development of job description of clinical dietitians in hospitals by the DACUM method. J Korean Diet Assoc. 2013; 19:265–286.

27. Nam TY, Kim JH. An evaluation of the effectiveness of nutrition counseling for adults with risk factors for dyslipidemia. Korean J Community Nutr. 2014; 19:27–40.

28. Lee HY, Kim HA, Yang IS, Nam CM, Park EC. Effectiveness of nutrition intervention: systematic review & meta-analysis. Korean J Community Nutr. 2004; 9:81–89.

29. Park EC, Kim HA, Lee HY, Lee YE, Yang IS. A review of the Medical Nutrition Therapy (MNT) of the U.S. medicare system. Korean J Community Nutr. 2002; 7:852–862.

30. Park HR, Cha JA, Lim YS. Performance and importance analysis of dietitian's task in public health nutrition areas. Korean J Community Nutr. 2008; 13:540–554.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download