This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major cause of disability, and according to statistics from the World Health Organization, COPD is the fourth leading cause of death overall in the face of decades, and expected to be increased. In 2005, the reported prevalence of COPD in Korea was 17.2% of adults over the age of 45. Malnutrition is a common problem in papatients with COPD. And several nutritional intervention studies showed a significant improvement in physical and functional outcomes. According to the results of previous studies, the nutritional support is important. This is a case report of a patient with COPD who was introduced to a proper diet through nutrition education based on the medical nutrition therapy protocol for COPD.

Keywords: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Medical nutrition therapy, Nutrition intervention

Introduction

Malnutrition is a common problem in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and its prevalence rates are 30-60% for inpatients and 10-45% for outpatients [

1]. Low body weight and low fat-free mass (FFM) have been recognized as unfavorable prognostic factors in patients with COPD [

2], and survival is reportedly only 2-4 years in severe patients who are lean and have a forced expiratory volume % in one second (FEV1%) < 50%. It has also been reported that COPD patients with body mass index (BMI) < 20 kg/m

2 are at higher risk of acute exacerbations than those with BMI ≥ 20 kg/m

2 [

3].

In patients with COPD, energy insufficiency due to decreased dietary intake caused by appetite loss associated with diminished general physical activity, a tendency toward depression, or dyspnea while eating is speculated to contribute to undernutrition [

4]. Conversely, enhanced energy expenditure due to the increased work of breathing may also contribute to undernutrition [

5]. As the third major cause of undernutrition in patients with COPD, the effects of humoral factors such as inflammatory cytokines, adipokines, and hormones on nutrition have been identified [

6].

A meta-analysis revealed weight gain and improved grip strength in patients with COPD receiving nutritional supplement therapy [

7]. In the Cochrane Review updated in 2012 [

8], the results of a meta-analysis of data from 17 randomized controlled trials revealed that nutritional supplement therapy induced body weight recovery and increased the FFM index with consequently improved exercise tolerance (6-minute walking distance) in undernourished patients with COPD. The results also provided evidence for a certain ameliorative effect of the therapy on inspiratory and expiratory muscle strength and health-related quality of life (St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire). A systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrates that nutritional support in COPD results in significant improvements in a number of clinically relevant functional outcomes [

9].

Registered dietitians should provide medical nutrition therapy (MNT) for patients with COPD that focuses on preventing and treating weight loss and other comorbidities [

10]. MNT is especially important for patients with COPD along with the following conditions:

Disease onset < 40 years of age

Frequent exacerbations (≥ 2 per year) despite adequate treatment

Rapidly progressive disease course (decline in FEV1, progressive dyspnea, decreased exercise tolerance, unintentional weight loss)

Severe COPD (FEV1 < 50% of predicted value) despite optimal treatment

Need for oxygen therapy

Onset of comorbid illness (osteoporosis, heart failure, bronchiectasis, lung cancer)

Possible indication for surgery

As in the studies presented, nutritional support is important in COPD. This case report reviews the nutritional support provided for one patient with COPD.

Case

The patient was a 70-year-old man with COPD. The patient had a history of numerous hospital treatments for acute exacerbation of COPD and had been maintaining his condition on home O2 (1-1.5 L) therapy for shortness of breath. The patient underwent lung volume reduction (LVR) on the right upper lobe (RUL) on August 15, 2012, had a valve removed from the existing RUL, and underwent LVR on the left upper lobe on 2012-12-18. After the LVR, the dyspnea worsened and performance was maintained at a level that only allowed movement around the house. Oxygen was used nearly every day and the patient did not leave the house. The dyspnea worsened 4-5 days prior to the hospital visit and reached a severe level on the day the patient visited the emergency room (December 27, 2013). After receiving intravenous treatment of levofloxacin and methyl prednisolone, the patient was admitted to the general ward (GW).

Immediately after admission, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit with drowsy mentality, and for 5 days after admission, 1600 kcal was administered via enteral tube feeding through an L-tube. When the patient became alert, the patient was transferred back to the GW on January 10, 2014 and the diet was switched to an oral soft diet. However, due to low consumption, 2 bags of medical food supplement were prescribed starting on January 21, 2014. On January 24, 2014 (27 days after admission), nutrition management was requested due to a continued low oral intake. This process is shown in

Figure 1.

Initial encounter

At the time of the first nutritional training on January 24, 2014, the patient's height and weight were 157.5 cm and 40.8 kg, BMI was 16.8 kg/m2, and percentage of ideal body weight was 75.8%, indicating that the patient was severely underweight. The patient's usual weight was 49 kg, and the patient had experienced an extreme weight loss of 14% during the 1 month. The patient's triceps skinfold measurement was 60% and mid-arm muscle circumference was 79%, figures accompanied by loss of both fat mass and FFM. No bioelectric impedance analysis (BIA) or bone mineral density (BMD) measurements were taken, and no parenteral nutrition, medical food supplement (Encover), or additional nutritional supplements (vitamins, omega-3 fatty acids) were prescribed.

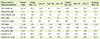

The patient was a senior who lived alone without a caregiver and had diminished masticatory function that made chewing foods difficult despite dentures. Although the patient did not have dysphagia, the patient had constipation but showed normal bowel movements or frequent small amounts of stool. Despite complaints of severe fatigue and dyspnea, the patient maintained a 3-meal-a-day diet and showed no changes in diet patterns. The patient tended to eat mainly rice and leave other foods nearly untouched, and the patient's daily consumption consisted of 1,500 kcal, including 45 g of protein (C:P:F = 75:12:13) and one packet of soymilk and an oral nutrition supplement. During the first nutritional education session, the diagnosis was determined to be severe malnutrition as a result of chronic disease. The nutrition diagnosis and intervention are shown in

Table 1.

First follow-up (F/U) encounter (3 days later)

At the first F/U 3 days later, the patient expressed at the interview, "I take breaks during the meal and finish everything including the side dishes. I drink one Encover. If I snack, I cannot eat much during the meal". With no significant changes in bowel movements, the patient's weight increased to 43.2 kg. There were no other changes to the patient's objective data. However, although the patient previously showed an activity level of barely being able to go to the washroom, the patient started walking around the ward supported by a walker. The patient demonstrated a diet exceeding the targeted nutritional requirement, but the patient's activity level increased. Since the patient's oxygen saturation was well maintained, the patient has not received a F/U after the measurement of 1/9 pCO

2 44.3 mmEq/L (normal range, 35-45), and no adverse effects of the excessive energy supplementation were observed. Hence, the nutritional requirement was reconsidered and increased, and the continuous maintenance of meal intake was encouraged. Another department suggested that if the current oral intake level is maintained, the nutritional supplement drinks should be discontinued. The nutrition diagnosis and intervention contents at the first follow-up encounter are shown in

Table 2.

Second F/U encounter (13 days later)

At the F/U 13 days later, the patient expressed at the interview, "I eat all that was provided, but it seems that the quantity of meals got smaller the last couple of days. In terms of feces, it is not diarrhea, but the frequency of bowel movement is similar". Since February 7, 2014, due to the change in prescription to the regular diet, the patient's dietary satisfaction decreased. The patient's weight was maintained at 42.2 kg with no changes, and the activity level was maintained at the walking level since the use of the walker. However, a slight increase in albumin and improved complete blood count indicators were observed; thus, any changes to the consistent diet maintenance were observed through objective indicators. Therefore, nutritional intervention was once again performed to ensure consistent diet maintenance and the patient was put on a high protein diet again. The nutrition diagnosis and intervention contents at the second follow-up encounter are shown in

Table 3.

At the time of discharge 1 week later, the patient's weight had increased to 44.8 kg and laboratory findings improved, demonstrating the positive effects of active nutritional support. The objective data of the patient is shown in

Table 4.

Discussion

This article is a case report of a patient with COPD. During a total of 50 days of hospitalization, 3 nutrition education sessions were provided after the first 30 days. The nutritional status at the time of the first nutrition education was at an extreme weight loss of 14% in 1 month along with severe malnutrition with drastic damage to the body muscles and fat. Movement was difficult, and the patient was dependent on oxygen for respiration. As a result of chewing difficulties due to tooth defects, approximately 1,600 kcal of nutrition consisting mainly of rice and drinks was consumed; however, the patient's diet mainly consisted of carbohydrates due to a lack of knowledge about the need to consume protein. Nutrition education was provided to improve the patient's nutritional status; as part of the treatment, the patient was educated on the methods of nutritional supplement intake as well as increasing the calorie and protein intakes. Changes to the patient's dietary intake and improvements in the nutritional indicators were collected via direct interview and electronic medical records after 3 days (second nutrition education session) and 10 days (third nutrition education session). The effects of the nutrition education intervention were then analyzed.

After the intervention, the energy and protein consumption in the patient's diet increased, improvements in the nutritional indicators (weight, laboratory data) were observed, and above all, an improved activity level that enabled movement was observed.

We have tried to adhere to COPD MNT in stages prior to the nutrition education [

10]. However, some parts of the nutrition assessment guideline were impractical, and a difference in the effects of the practical method suggested by the nutrition intervention for a more effective diet were recognized. Furthermore, the shortcomings of the current nutritional management provided to patients with COPD were evident.

The first shortcoming is related to the difficulty assessing quality of life (QOL). For the average patient who is not a participant of a study, it is impractical to assess QOL using the available tools and the limited amount of time and human resources. In addition, the guideline suggests an assessment of the ability to prepare and consume a meal according to a patient's nutritional requirements. However, in this case, the patient was a senior who lived alone and used home oxygen. In the first month of hospitalization, the patient was in no condition to benefit from nutritional intervention.

Second, the BIA of patients with COPD who are not research participants cannot be assessed, and the need for BMD assessment is not well recognized and cannot be assessed.

Third, it was difficult to use frequent small amounts of medical food supplements for this patient. With snack consumption, the patient complained of difficulty fully consuming all 3 meals. Since the patient's nutritional requirements were well exceeded with meals alone, the active use of medical food supplements was not suggested; rather, a tailored method of nutritional intervention was required. In addition, there were practical difficulties in recommending vitamins and omega-3 fatty acids due to the patient's low recognition of their benefits and increase in medical expenses.

Fourth, the current state of nutrition management for patients with COPD is disappointing. Although our patient met 6 of 7 nutrition management target categories as suggested by COPD MNT, the patient's status of malnutrition continued to progress 1 month after admission; further, nutrition management was requested, demonstrating the need for an active nutrition management starting at the time of admission. With this patient in particular, the lack of nutrition intervention at the time of admission was disappointing, especially given the significant increases in the patient's food consumption following the nutrition education sessions and dietary changes.

Significant improvements in physical and functional outcomes as a result of nutritional support have been reported in systematic reviews and meta-analyses [

7,

8,

9]. Likewise, in this case, improvements in weight, laboratory data, and motor abilities were observed. To achieve a more effective nutrition intervention in the future, systematic nutrition management, continuous data reporting, and the use of an interdisciplinary team approach are needed.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download