Abstract

The objective of this article is to report improvement of nutritional status by protein supplements in the patient with protein-losing enteropathy. The patient was a female whose age was 25 and underwent medical treatment of Crohn's disease, an inflammatory bowl disease, after diagnosis of cryptogenic multifocal ulcerous enteritis. The weight was 33.3 kg (68% of IBW) in the severe underweight and suffered from ascites and subcutaneous edema with hypoalbuminemia (1.3 g/dL) at the time of hospitalization. The patient consumed food restrictively due to abdominal discomfort. Despite various attempts of oral feeding, the levels of calorie and protein intake fell into 40-50% of the required amount, which was 800-900 kcal/d (24-27 kcal/kg/d) for calorie and 34 g/d (1 g/kg/d) for protein. It was planned to supplement the patient with caloric supplementation (40-50 kcal/kg) and protein supplementation (2.5 g/kg) to increase body weight and improve hypoproteinemia. It was also planned to increase the level of protein intake slowly to target 55 g/d in about 2 weeks starting from 10 g/d and monitored kidney load with high protein supplementation. The weight loss was 1.0 kg when the patient was discharged from the hospital (hospitalization periods of 4 weeks), however, serum albumin was improved from 1.3 g/dL to 2.5 g/dL and there was no abdominal discomfort. She kept supplement of protein at 55 g/d for 5 months after the discharge from the hospital and kept it at 35 g/d for about 2 months and then 25 g/d. The body weight increased gradually from 32.3 kg (65% of IBW) to 44.0 kg (89% of IBW) by 36% for the period of F/u and serum albumin was kept above 2.8 g/dL without intravenous injection of albumin. The performance status was improved from 4 points of 'very tired' to 2 points of 'a little tired' out of 5-point scale measurement and the use of diuretic stopped from the time of 4th month after the discharge from the hospital owing to improvement in edema and ascites. During this period, the results of blood test such as BUN, Cr, and electrolytes were within the normal range. In conclusion, hypoproteinemia

and weight loss were improved by increasing protein intake through utilization of protein supplements in protein-losing enteropathy.

Protein-losing enteropathy means all diseases that show hypoproteinemia due to protein loss through gastrointestinal tract, and it shows various symptoms such as edema, diarrhea and malabsorption according to the related diseases [1-3]. The disease group related with protein-losing enteropathy is divided into three cases such as the case that is caused by damage of mucosal cells in gastroenteric duct without inflammation or ulcer, the case that is caused by inflammation or ulcer of mucous membrane and the case that the pressure increases by disorder in lymphatic duct, and it is related with various diseases [4]. Protein-losing enteropathy caused by inflammatory bowel diseases is included in protein loss caused by inflammation or ulcer of mucous membrane. Regarding its mechanism, it can occur as the intestinal juice which has affluent protein is loss due to inflammation or ulcer of mucous membrane and lymph that has affluent protein is loss as lymphatic duct gets expanded by the secondarily-damaged mucosal cells or protein can be lost excessively by the infection [5].

Twenty to seventy-five percent of inflammatory bowel disease patients show the malnutrition that accompanies with weight loss, however, it is related with reduction of nutrition intake due to abdominal pain and restricted meal, malabsorption due to reduction of absorbent surface and increase of intestinal loss such as protein-losing enteropathy. According to several researches [2,4-6], it was reported that there was insufficiency of various nutrients such as protein, vitamin and minerals in the patients of inflammatory bowel diseases, and it was known that especially protein-energy malnutrition influences on quality of life and it is very important factor of death rate or incident rate as it is highly-related with weight loss, increase of sensibility against infection and delay of wound healing. Especially, malnutrition of protein has been reported from 20-85% of Crohn's disease. According to Valentini et al. [7], it shows that proper intake of nutrients that can keep balance of protein is important from such patients as it reported there were 24-36% of malnutrition out of inflammatory bowel disease patients. In our hospital, the treatment is being implemented in accordance with the patient of inflammatory bowel diseases and nutritional status of the patients with protein-losing enteropathy are being improved by protein supplements.

In this paper, we reported the improvement case of one patient who was underwent medical treatment that was approved by Institutional Review Board.

The patient is a female whose age is 25 and undergoing medical treatment of Crohn's disease that is an inflammatory bowel disease after diagnosis of cryptogenic multifocal ulcerous enteritis and the nutrition team received the request to attempt high protein meal to improve hypoalbuminemia along protein-losing enteropathy.

The patient suffered from anemia continuously since when she was 4 years old, but could not find the specific reason for that, however, while implementing capsule endoscope to find the reason, the capsule was stuck at the upper part of ileum then the patient took small bowel resection. At that time, weight was normal by 49.4 kg (100% of IBW), but it decreased down to 37.0 kg (75% of IBW) by 25% for a year as weight loss continued, then reached the status of severe underweight at 33.3 kg (68% of IBW) at the time of hospitalization in 2010. She also suffered from ascites and subcutaneous edema with hypoalbuminemia (1.3 g/dL), however, abdominal discomfort and edema of face occurred from 2007 and diuretic was used to control ascites from 2009. She took the injection of albumin intermittently as the outpatient to improve hypoalbuminemia, but there was no effect.

The patient was in severe underweight that was included in 68% of IBW with 153 cm height and 33.3 kg body weight and in excessive malnutrition of protein-energy that marasmus was mixed at total protein by 2.7 g/dL and albumin by 1.3 g/dL from biochemical examination. Other blood test indices were 89 mg/dL for cholesterol, 7.5 for BUN, 0.28 Cr, 6.9 mg/dL for Ca, 33/19 IU/L for AST/ALT, 8.1 g/dL for hemoglobin, and 1.7 for CRP.

The foods for the patient were extremely restricted due to abdominal discomfort and the varieties were limited. In case of eating out, the symptoms of abdominal pain and diarrhea appeared and had meals at home most of the time. According to survey results of her dietary history, the patient consumed spinach and broccoli only after complete boiling and avoided the intake of other vegetables because she thought abdominal discomfort got worse if she had high-fiber foods. The patient appealed that abdominal discomfort occurred even when she consumed a bottle of vegetable juice little by little for a whole day. In case of ingesting fruits, she limited the quantity because she had burning feeling in her stomach because of sourness of the fruits. The patient also did not like the sweet taste of fruits, and there was nearly no intake of fruits. The patient had the meals mainly with rice and some fishes she could eat and intake of most nutrients such as calorie, carbohydrate, fat, protein, vitamin and minerals was very insufficient below 30-40% of required amount.

The foods the patient had were too limited considering her preference and abdominal discomfort. However, the motive and participation of the patient were willing to be induced to increase the intake by setting the goal of nutrition management so that she could minimize the supply of intravenous alimentation and increase oral feeding as much as possible considering that she was in the condition that could use gastrointestinal tract as an young female who were supposed to do social activities actively. First, low reside diet with low contents of dietary fiber was provided and supplementary snack was provided two or three times a day for the purpose of reducing discomfort and increase intake, although the amount was only slightly increased due to abdominal discomfort. Standard formula such as Ensure and Greenbia which have low contents of fiber as the nutritional supplementing beverage was recommended and tried, but the patient appealed the abdominal pain after ingesting them. And component nutrition solution (Monowell) that was produced for purpose of providing the nutrients to the patient of colitis was tried, but it could not be continued because she appealed abdominal discomfort. Despite the efforts of increasing oral feeding in various types, the intake was 800-900 kcal, 34 g protein (24-27 kcal/kg, 1 g/kg) a day falling into 40-50% of required intake, and it was insufficient to satisfy with the required intake though it increased comparing with the time of entering the hospital.

Because it was difficult to increase oral feeding, supplementation of calories and protein were required to increase the weight and improve hypoproteinemia. After discussion with the medical team, the use of protein supplement was suggested. The references of Umar & DiBaise [8] and Braamskamp et al. [9] that recommended 2.0-3.0 g protein/kg/day were referred for positive balance of protein in protein-losing enteropathy and the goal of nutrient supply was set to 40-50 kcal/kg and 2.5 g protein/kg considering the condition of excessive underweight. Nutrition intervention was implemented continuously to increase oral feeding by providing gruel or soup as the snack and insufficient protein from oral feeding was supplemented with protein supplement (Promax, >90% protein) (Table 1).

It was guided to take protein supplement with the meal by providing it twice a day for breakfast and dinner after discussion with the patient and instructed her to consume protein supplement with gruel, water and yogurt in the way that the patient could eat. Twenty g was provided a day when providing protein supplement at first, but actual intake stopped at degree of 1/2 and it was increased up to target goal 55 g slowly for about 2 weeks starting from intake of protein 10 g a day considering adaptability of the patient, and the adaptability was good for the period of increase without abdominal discomfort. Blood testing including BUN, Cr, and electrolytes was monitored monitored continuously to check load on kidney along intake of high protein meal (2.5 g protein/kg). The patient discharged from the hospital about 4 weeks after hospitalization, however, there was weight loss by 1.0 kg from 33.3 kg to 32.3 kg while ascites were controlled and stabilized after treatment and serum albumin was improved from 1.3 to 2.5. She discharged from the hospital in the condition without discomfort after increasing protein powder up to target amount.

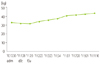

After discharge, she visited the hospital regulary as the outpatient for about 10 months and was managed (total 8 times by every 2 weeks and one-two months after discharge). She kept 55 g (morning 30, lunch 5, dinner 20) of protein supplements for about 5 months and 35 g for about 2 months and 25 g along the improvement of the patient. Body weight increased gradually from 32.3 kg (65% of IBW) to 44.0 kg (89% of IBW) by about 36% for the period of continuous management (Figure 1) and serum albumin concentration was kept above 2.8 in average without the injection of albumin (Figure 2). And, the performance status that the patient felt was improved from 4 points of 'very tired' to 2 points of 'a little tired' out of 5-points scale measurement and input of diuretic stopped owing to the improvement of edema and ascites from the time of 4th month after discharging from the hospital. During this period, the results of blood test such as BUN, Cr and electrolytes were within the normal range.

Albumin is the water soluble molecule and plays the role of transporting various hormones, fatty acids, ions and bilirubin as the transport protein. The normal range of albumin loss through intestinal canal is within 10% of total albumin, and protein loss through digestive system does not become the problem because 6-10% is dissolved and the same amount is synthesized every day in a healthy adult. However, albumin loss increases up to about 60% and protein synthesis in the liver increases about 24% in protein-losing enteropathy, and then hypoalbuminemia appears by its excessive loss because albumin loss cannot catch up its synthesis [9]. Hypoalbuminemia shows ascites and subcutaneous edema sometimes and can cause the restriction in daily life and deterioration of disease due to the degeneration of overall health. Therefore, the improvement of hypoproteinemia can be the important factor for medical treatment of the patient and sufficient amount of protein supplement is recommended [8].

High calories and high protein meal is recommended for the patient of inflammatory bowel disease, and in case of protein, 1.0-1.5 g/kg/day [2] or 1.5-1.75 g/kg/day [10] is recommended for the adult in general, but more aggressive supply of protein than that is required for the patient of protein-losing enteropathy. Umar & DiBaise [8] reported there was no effect of improving hypoproteinemia when protein of less than 2.0 g/kg/day was provided in case of protein-losing enteropathy patient who had heart failure by nature.

Braamskamp et al. [9] recommended high protein meal for the patient of protein-losing enteropathy because intermittent intravenous injection of albumin was not helpful for long-term and recommended to use the commercial protein supplement if necessary. Umar & DiBaise [8] and Braamskamp et al. [9] recommended protein by 0.6-0.8 g/kg/day and 0.66 g/kg/day for normal adults in general and recommended to increase the supply of protein up to 2.0-3.0 g/kg/day and 1.5-3.0 g/kg/day each for positive balance of protein for the patient of protein-losing enteropathy. Ballinger & Farthing [11] did not mention protein for the patient of protein-losing enteropathy who had lymphangiectasia together, but recommended low fat meal supplemented medium chain fatty acid. Braamskamp et al. [9] recommended to supply fat by implementing high protein meal, restricting long chain fatty acid and replacing it with medium chain fatty acid, however, in this case, the patient ingested low fat meal whose long chain fatty acid is restricted considering her dietary habits, but medium chain fatty acid was not provided additionally. As one of the reasons for protein-losing enteropathy, the increase of pressure by disorder of lymphatic duct can be considered, however, as medium chain fatty acid is absorbed directly to portal vein without passing through lymphatic duct and can increase supply of calories, the supplement of medium chain fatty acid can be considered together with the supplement of protein in further researches. At this time, the supplement of essential fatty acid should be considered because essential fatty acid cannot be provided with medium chain fatty acid only.

The patient was hospitalized once to four times for a year after 2005 due to main complaint of abdominal pain and poor intake and the period of hospitalization was 3 days to a month. But, while the patient was supplementing protein after discharging from the hospital for one year and 6 months up to now, her condition was improved as much as she took regular medical treatment only as the outpatient without hospitalization and the effect of supplementing protein has been sustained for long time considerably.

Protein-losing enteropathy appears related with various diseases and its medical treatment cures the underlying diseases that become the reasons. At this time, it is not reasonable to regard the condition of the patient was improved only with supplement of protein from high protein meal because meal, medicine and operational intervention are performed in parallel, but there is no doubt that sufficient supply of protein plays an important role of improving the body weight and nutritional status of the patient. Also, protein-losing enteropathy is the very rare disease in both domestic and foreign cases and its frequency of occurrence or prevalence were not known, and especially meal or nutrition management-related reports were very insufficient. Therefore, it is considered that the aspect of improving hypoproteinemia together with weight gain by increase of protein and calorie intakes and periodic nutrition management by using protein supplements in the patient of protein-losing enteropathy with edema and hypoproteinemia in this case would be a meaningful precedent, and it is also considered that the aggressive management by the clinical dietitians as soon as possible would be helpful for these patients.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Han SH, Lee OY, Eun CS, Roh BJ, Sohn W, Baeg SS, Yoon BC, Choi HS. A case of protein-losing enteropathy associated with small bowel villous atrophy. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2007. 49:31–36.

2. Escott-Stump S. Nutrition and diagnosis-related care. 2002. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

3. Lee HL, Han DS, Kim JB, Jeon YC, Sohn JH, Hahm JS. Successful treatment of protein-losing enteropathy induced by intestinal lymphangiectasia in a liver cirrhosis patient with octreotide: a case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2004. 19:466–469.

4. Ferrante M, Penninckx F, De Hertogh G, Geboes K, D'Hoore A, Noman M, Vermeire S, Rutgeerts P, Van Assche G. Protein-losing enteropathy in Crohn’s disease. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2006. 69:384–389.

5. Ungaro R, Babyatsky MW, Zhu H, Freed JS. Protein-losing enteropathy in ulcerative colitis. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2012. 6:177–182.

6. Baert D, Wulfrank D, Burvenich P, Lagae J. Lymph loss in the bowel and severe nutritional disturbances in Crohn's disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999. 29:277–279.

7. Valentini L, Schaper L, Buning C, Hengstermann S, Koernicke T, Tillinger W, Guglielmi FW, Norman K, Buhner S, Ockenga J, Pirlich M, Lochs H. Malnutrition and impaired muscle strength in patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in remission. Nutrition. 2008. 24:694–702.

8. Umar SB, DiBaise JK. Protein-losing enteropathy: case illustrations and clinical review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010. 105:43–49.

9. Braamskamp MJ, Dolman KM, Tabbers MM. Clinical practice. Protein-losing enteropathy in children. Eur J Pediatr. 2010. 169:1179–1185.

10. Nelms MN. Nutrition therapy and pathophysiology. 2002. 2nd ed. Belmont: Wadsworth.

11. Ballinger AB, Farthing MJ. Octreotide in the treatment of intestinal lymphangiectasia. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998. 10:699–702.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download