Abstract

Primary diffuse leptomeningeal gliomatosis (PDLG) is a rare condition with a fatal outcome, characterized by diffuse infiltration of the leptomeninges by neoplastic glial cells without evidence of primary tumor in the brain or spinal cord parenchyma. In particular, PDLG histologically diagnosed as gliosarcoma is extremely rare, with only 2 cases reported to date. We report a case of primary diffuse leptomeningeal gliosarcomatosis. A 68-year-old man presented with fever, chilling, headache, and a brief episode of mental deterioration. Initial T1-weighted post-contrast brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement without a definite intraparenchymal lesion. Based on clinical and imaging findings, antiviral treatment was initiated. Despite the treatment, the patient's neurologic symptoms and mental status progressively deteriorated and follow-up MRI showed rapid progression of the disease. A meningeal biopsy revealed gliosarcoma and was conclusive for the diagnosis of primary diffuse leptomeningeal gliosarcomatosis. We suggest the inclusion of PDLG in the potential differential diagnosis of patients who present with nonspecific neurologic symptoms in the presence of leptomeningeal involvement on MRI.

Leptomeningeal gliomatosis is a condition characterized by widespread extension into the leptomeninges and seeding in the subarachnoid space of glial tumor cells. Most cases of leptomeningeal gliomatosis are the secondary spreads of neoplastic glial cells from primary intraparenchymal glioma, which usually occur late in the development of malignant glioma. Primary diffuse leptomeningeal gliomatosis (PDLG), which arises primarily in the leptomeninges without evidence of a primary parenchymal tumor of the central nervous system (CNS), is a very rare presentation of a glial tumor, with less than 90 patients reported to date [1]. It is a very aggressive and fatal disease with various grades of histopathology including glioblastoma, anaplastic astrocytoma, anaplastic oligoastrocytoma, anaplastic oligodendroglioma, oligodendroglioma, ependymoblastoma, primitive neuroectodermal tumor, and low-grade astrocytoma [2]. Among the reported patients with PDLG, there are only two cases diagnosed histopathologically as gliosarcoma [3,4]. Gliosarcoma is a rare primary malignant CNS neoplasm composed of an admixture of gliomatous and sarcomatous components, accounting for approximately 2% of all cases of glioblastoma [5]. It is an aggressive neoplasm with poor prognosis, classified as Grade IV neoplasm in the World Health Organization classification scheme. We present an extremely rare case of PDLG histopathologically diagnosed as gliosarcoma, which can be referred to as primary diffuse leptomeningeal gliosarcomatosis.

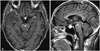

A 68-year-old man with an untreated pituitary mass was referred to the department of neurology due to fever, chilling, headache, and a brief episode of mental deterioration. Neurologic examination at the first presentation was normal. T1-weighted post-contrast brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement prominently along the right frontal, right operculum, right temporal, left cerebellum, left ambient cistern, interpeduncular cistern, bilateral sylvian fissure, and cervicomedullary junction without any massive intra-axial involvement (Fig. 1). On this MRI, there is no interval change of the pituitary lesion compared to the MRI taken two years prior.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed a normal opening pressure of 80 mm H2O, one white blood cell/mm3, a slightly elevated protein level of 50.5 mg/dL, a normal glucose level, and adenosine deaminase activity of 1.6 U/L. Based on clinical and imaging findings, a diagnosis of probable viral meningoencephalitis was made by a neurologist, and antiviral drug treatment (acyclovir 1,500 mg/day) and steroid treatment (dexamethasone 20 mg/day) were started.

Cultures and serology of serum and CSF were negative for bacteria, virus, fungi, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 was negative. Extensive laboratory evaluations for infectious and inflammatory causes of meningitis were negative. Cytologic examination of CSF was not performed.

After two weeks of treatment with acyclovir and dexamethasone, the patient's symptoms including fever and headache improved, and he exhibited a more alert mentality. However, unlike the improvement in clinical symptoms, the follow-up brain MRI taken one month after the completion of antiviral treatment showed no definite interval change in the extent of enhancing lesions. Since tumorous conditions including lymphoma, leptomeningeal carcinomatosis, and leptomeningeal gliomatosis were suspected based on the MRI findings, whole-body positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) was performed. A whole-body PET-CT showed intense fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the leptomeningeal enhancing lesions on MRI without other significant increased uptake in the whole body area except the pituitary gland (Fig. 2). A biopsy of the leptomeningeal lesions for pathologic diagnosis was recommended due to the malignancy indications of these findings, but the patient and his family refused biopsy and did not attend follow-up examinations.

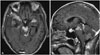

Three months later, he revisited our emergency room with intractable headache, diplopia, confusion, and progressive deterioration of mental status. Further MRI of the brain showed rapid disease progression with expansion of leptomeningeal enhancement throughout the brain, multiple cranial nerve infiltration of lesions, and exacerbation of parenchymal edema adjacent to the leptomeningeal enhancing lesions (Fig. 3).

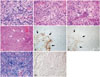

Open surgical biopsy of the temporal leptomeningeal lesion was performed via right frontotemporal craniotomy. The intraoperative findings revealed a pinkish tumor mass with high vascularity that firmly adhered to the dura mater and was easily separated from the brain cortex. Histopathologic examination revealed a highly proliferative tumor with markedly increased nuclear Ki-67 staining that had a biphasic component of glial and sarcomatous cells. In the glial component, there were microvascular proliferations and areas of necrosis, and the number of mitotic figures per 10 high-power fields was 5-6, and the Ki-67 labeling index at the hot spot was 20%. The glial component showed hyperchromatic features with high cell density and stained positive using antibodies against glial markers including glial fibrillary acidic protein and oligodendrocyte lineage transcription factor 2. In the sarcomatous component, the number of mitotic figures per 10 high-power fields was 2-3, and the Ki-67 labeling index at the hot spot was 10%. The sarcomatous component, which is composed of interweaving fascicles of spindle cells, was negative for glial marker, yet positive for reticulin and trichrome, showing surrounding abundant reticular fibers and collagens. Therefore, the pathological diagnosis of gliosarcoma was established (Fig. 4). Immunohistochemical analysis showed wild-type isocitrate dehydrogenase 1, and it was confirmed by direct sequencing. Me-thylation-specific PCR showed O-6-methylguanine methyltrans-ferase promoter methylation. Intact 1p and 19q were detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization. p53 showed nuclear positivity in almost 20% of tumor cells.

We planned whole-brain radiotherapy with concurrent administration of temozolomide for the patient postoperatively. While preparing for the adjuvant treatment, the patient's condition deteriorated rapidly to stuporous mental status despite mannitolization and steroid therapy for controlling the intracranial pressure. The patient's family strongly forbade adjuvant treatment, and the patient was transferred to a local hospital for palliative care. He expired soon after, five months after initial presentation; an autopsy was not performed.

Primary leptomeningeal glioma is a rare condition with unclear etiology. Two major anatomical and clinical forms of primary leptomeningeal glioma have been described: a solitary form and a diffuse form. A solitary form has been described as a limited solitary mass in cranial or spinal leptomeninges that mimics an extra-axial CNS tumor. We presented a case of solitary primary leptomeningeal glioma in our previous report [6]. A diffuse form described as a diffuse extension of glial tumor cells over a wide area of the CNS without intra-axial mass constitutes the majority of primary leptomeningeal glioma, and has a more dismal prognosis than the solitary form [7]. In the present report, we described a rapidly progressive case of PDLG histologically diagnosed as gliosarcoma with fatal outcome.

The diagnosis of PDLG should satisfy the three following criteria [8]: 1) no apparent attachment of extramedullary meningeal tumor to the neural parenchyma, 2) no evidence of primary neoplasia within the neuraxis, and 3) the existence of distinct leptomeningeal encapsulation around the tumor. Prior to the advance of high-resolution imaging, the definitive diagnosis of PDLG, thus, required autopsy to rule out a primary parenchymal source of the leptomeningeal spread. The development of gadolinium-enhanced MRI has significantly increased the ability to diagnose PDLG. Our case successfully satisfied the three criteria for diagnosis of PDLG.

Nevertheless, our case highlights the difficulty in diagnosing PDLG. The clinical presentation, CSF findings, and neuroimaging results observed in PDLG are nonspecific. Clinical presentations of PDLG usually appear to develop in two stages. The prodromal phase consisted of various signs of subacute meningitis or encephalomyelitis, and a second phase consists of nonspecific neurological impairment, which could mimic numerous neurological diseases [2,7]. There are various signs and symptoms that PDLG may manifest, including headache, nausea, vomiting, meningismus, cranial nerve palsy, seizure, and mental state alteration [2]. CSF examination in patients diagnosed with PDLG usually reveals high protein levels, normal or minimally decreased glucose concentrations, and low or moderate pleocytosis [9]. However, the result of CSF examination of PDLG varies from case to case. Unlike in secondary meningeal gliomatosis or leptomeningeal carcinomatosis, the identification of malignant cells via CSF cytologic examination is very rare in PDLG [10]. Because of these symptomatic features and equivocal results of CSF examination, infectious, inflammatory, granulomatous, and neoplastic conditions were all considered at various stages of the clinical course. It is common for PDLG to be initially considered an infectious condition and to be mistreated with antituberculous, antiviral, or antifungal therapy, because the clinical and CSF findings resemble those of chronic infectious meningitis. Our patient initially presented with symptoms of meningoencephalitis such as fever, chilling, and headache, and the MRI showed diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement, which can be observed in infectious conditions. In addition, CSF analysis in our patient was not compatible with bacterial or tuberculous meningitis. Based on these clinical and imaging findings, the patient was initially misdiagnosed with viral meningoencephalitis and treated with antiviral agents and steroids. There was an ephemeral improvement in the patient's symptoms, but the patient worsened both clinically and radiologically.

To our knowledge, this is the third reported case of PDLG histologically diagnosed as gliosarcoma. As the first [3] and second [4] reports of primary diffuse leptomeningeal gliosarcomatosis, diffuse meningeal involvement at the time of presentation without parenchymal lesion in our case supports the fact that the gliomatous and sarcomatous components of gliosarcoma are derived from a monoclonal origin, and PDLG arises from nests of heterotopic glial tissue. In addition, our case illustrates the fatal and rapidly progressive nature of the untreated disease with severe aggravation of the clinical condition and serial MRI of the patient.

When diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement is evident on the MRI of the neuraxis, diagnosis can be very challenging. We suggest the inclusion of PDLG in the potential differential diagnosis of patients who present with nonspecific neurologic symptoms in the presence of leptomeningeal involvement on MRI. Early meningeal biopsy is strongly recommended in patients who fail to respond to first-line treatments for infectious conditions with worsening neurological symptoms.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Axial (A) and sagittal (B) T1-weighted post-contrast magnetic resonance imaging showed diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement prominently along the right frontal, right operculum, right temporal, left cerebellum, left ambient cistern, interpeducluar cistern, bilateral sylvian fissure, and cervicomedullary junction without any massive intraaxial involvement. |

| Fig. 2Axial image (A) of the whole-body positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) showed intense fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake in the leptomeningeal enhancing lesions on magnetic resonance imaging (arrows). Coronal image (B) of the PET-CT showed linear increased FDG uptake throughout the cervical and upper thoracic spinal cords (arrows). These findings were suggestive of leptomeningeal involvement of malignancy. |

| Fig. 3Axial (A) and sagittal (B) T1-weighted post-contrast magnetic resonance imaging showed rapid disease progression with expansion of leptomeningeal enhancement throughout the brain, multiple cranial nerve infiltration of lesions, and exacerbation of parenchymal edema adjacent to the leptomeningeal enhancing lesions. |

| Fig. 4Photomicrographs. A: Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain of the astrocytic component of the tumor (×400) is shown. B: A portion of the tumor demonstrated sarcomatous, spindle morphology (H&E stain, ×400). C: Microvascular proliferation (arrows) was observed throughout the glial component (H&E stain, ×400). D: Presence of areas of pseudopalisading necrosis (arrows) in the glial component (H&E stain, ×100). E and F: Focal glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and oligodendrocyte lineage transcription factor 2 (OLIG2) staining (×100) is evident in the astrocytic portion of the gliosarcoma (arrows). By contrast, the sarcomatous portion is negative for GFAP and OLIG2. G and H: The sarcomatous component is rich in trichrome (G) and reticulin (H) (×200). |

References

1. Yamasaki K, Yokogami K, Ohta H, et al. A case of primary diffuse leptomeningeal gliomatosis. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2014; 31:177–181.

2. Debono B, Derrey S, Rabehenoina C, Proust F, Freger P, Laquerrière A. Primary diffuse multinodular leptomeningeal gliomatosis: case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 2006; 65:273–282. discussion 282.

3. Watanabe Y, Hotta T, Yoshioka H, Itou Y, Taniyama K, Sugiyama K. Primary diffuse leptomeningeal gliosarcomatosis. J Neurooncol. 2008; 86:207–210.

4. Dimou J, Tsui A, Maartens NF, King JA. Primary diffuse leptomeningeal gliosarcomatosis with a sphenoid/sellar mass: confirmation of the ectopic glial tissue theory? J Clin Neurosci. 2011; 18:702–704.

6. Kim YG, Kim EH, Kim SH, Chang JH. Solitary primary leptomeningeal glioma: case report. Brain Tumor Res Treat. 2013; 1:36–41.

7. Keith T, Llewellyn R, Harvie M, Roncaroli F, Weatherall MW. A report of the natural history of leptomeningeal gliomatosis. J Clin Neurosci. 2011; 18:582–585.

8. Cooper IS, Kernohan JW. Heterotopic glial nests in the subarachnoid space; histopathologic characteristics, mode of origin and relation to meningeal gliomas. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1951; 10:16–29.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download