CASE REPORT

A 58-year-old woman was admitted with a headache and dizziness that had persisted for one week. Upon neurological examination, she demonstrated left hemifacial numbness due to left fifth cranial nerve palsy and diplopia at left gaze due to left sixth cranial nerve palsy. The patient did not exhibit ataxic gait, and her brain stem reflex and cerebellar signs were intact. She did not complain of tinnitus and did not exhibit nystagmus. She did not have histories of hypertension or diabetes mellitus.

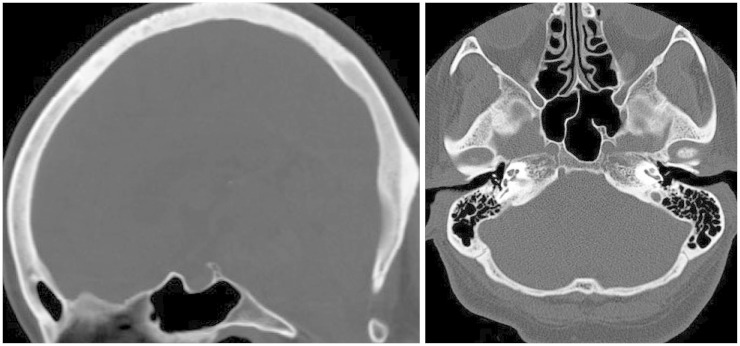

A computed tomographic (CT) scan revealed a 43×21 mm round mass in the retroclival and prepontine region. Abnormal findings were not observed in the clivus or surrounding bony structure and the posterior cortical lining of the clivus was intact (

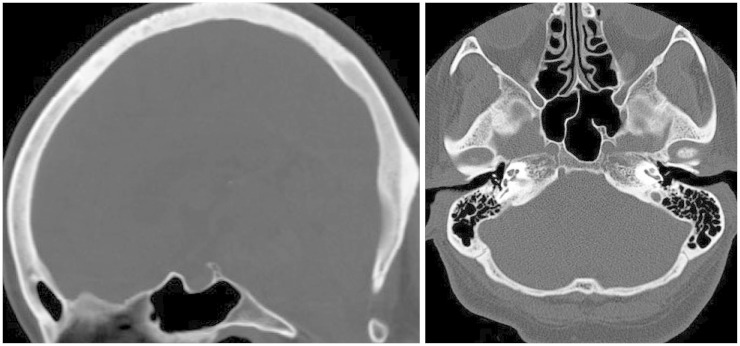

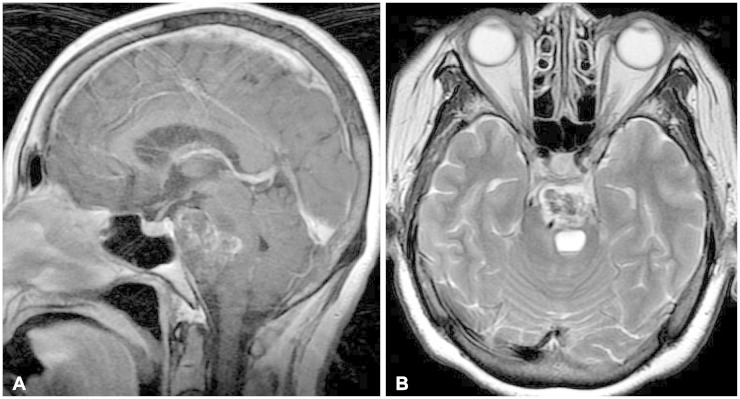

Fig. 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed heterogeneous high signal intensity of the mass in T2-weighted images (WI) and iso-signal intensity in T1WI (

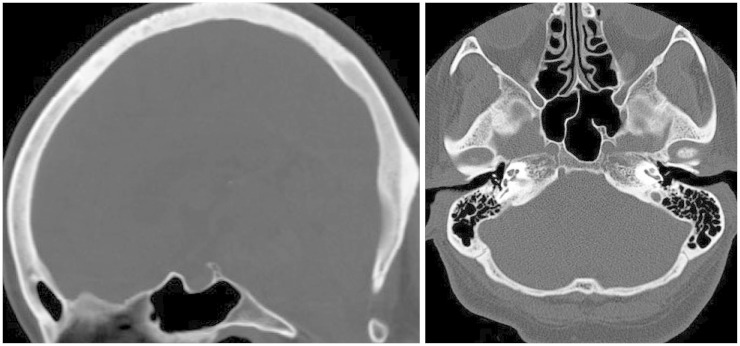

Fig. 2A, B). The mass revealed heterogeneous enhancement with gadolinium (

Fig. 2C,

3A). The pons was severely compressed by the mass and contained a cystic lesion showed by high signal intensity in T2WI and iso-signal intensity in T1WI (

Fig. 3B). The basilar artery was not surrounded by the mass and was displaced to the right side. We did not detect a vascular lesion in MR angiography.

| Fig. 1Computed tomographic scan showing a normal appearance of clivus and intact cortical lining of posterior clival surface.

|

| Fig. 2Retroclival and prepontine mass with severe compression of pons in T2-weighted image (A) and T1-weighted image (B), with gadolinium enhancement (C).

|

| Fig. 3Gadolinium enhancement of sagittal image (A), cystic lesion in pons on T2-weighted image (B).

|

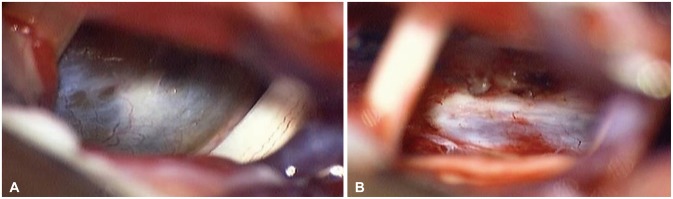

We performed surgery via the left retro-labyrinthine transpetrosal approach. After petrosectomy and incision of the petrosal dura and tentorium, a grayish mass covered by arachnoid membrane was exposed between the cranial nerves (

Fig. 4A). The left fifth and sixth cranial nerve were displaced laterally by the mass, but the other cranial nerve was not. The mass was very friable and easily removed by suction tools. The mass consisted of yellowish, dark material that resembled old hematoma was first removed and then decompressed internally. The sixth cranial nerve was then released and easily detached from the mass capsule. The sixth cranial nerve did not adhere to the mass capsule. The extension of the mass to the pons was safely separated and the pontine surface in contact with the mass was founded intact by mirror. Although the last piece of the mass was attached to the clival dura of a tiny surface, it was easily separated from the dura and there was no penetration or invasion (

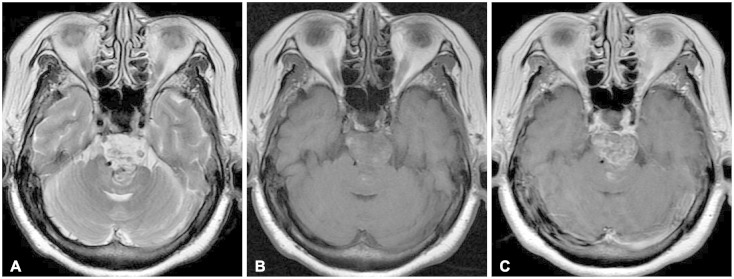

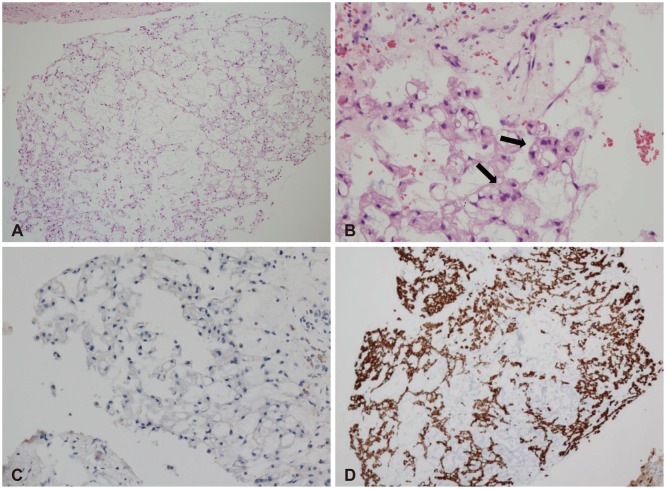

Fig. 4B). The basilar artery was not encased by the tumor, and the cranial nerves on the opposite side were well separated from the mass. The mass was completely removed without injury to the cranial nerves or pons. The final pathological diagnosis was confirmed to be typical chordoma with nuclear atypia (

Fig. 5A, B). Immunohistochemical stains demonstrated positive keratin AE1/AE3 and epithelial membrane antigen but negative Ki 67 index (

Fig. 5C, D). There was an absence of mitoses and necrosis.

| Fig. 4Intraoperative photographs: exposed mass between 5th and 7, 8th cranial nerves (A), intact retroclival dura after resection of mass (B).

|

| Fig. 5Typical physaliphorous cells forming cord or nest within myxoid background (H&E, ×40) (A) and nuclear atypia (black arrows) (×400) (B), negative immunohistochemical staining for Ki 67 antigen (×200) (C), positive immunohistochemical staining for keratin AE1/AE3 (×40) (D).

|

Postoperatively, the patient gradually recovered from her cranial nerve palsy, diplopia and left hemifacial numbness. No other neurological deficits were found. Twelve months after the operation, we detected no recurrence of the mass on MR images and the cystic lesion in the pons had decreased in size.

Go to :

DISCUSSION

Embryologically, the primitive notochord exists to support axis within bony structures, such as the sella turcica, clivus, and vertebral column. During fetal development, the notochord regresses and disappears within the bony structures but grows between them and alters mucoid degeneration. The notochord ultimately becomes the nucleus pulposus of the intervertebral disc in the fully developed fetus. Remnants of the primitive notochord formed during these developmental processes tend to have neoplastic activity that may lead to chordoma [

7]. Chordomas typically occur along the neuraxis, especially at the cranial and caudal ends. Intracranial chordomas arise mostly in the sphenoocciptal synchondrosis of the clivus and rarely in the sphenoid sinus, sella turcica, or foramen magnum. Chordomas are associated with intraosseous extension, bony destruction and intradural invasion. Most chordomas have malignant courses and metastatic spread can occur by the hematogenous route to lung, liver, lymph node and peritoneum.

Twenty seven cases of intracranial intradural chordoma have been reported to the best of our knowledge. Lesions were located in the prepontine-retroclivus in 19 cases, the suprasellar region in 3 cases, and the intrasellar, tentorium, foramen magnum, cerebellar, and ponto-cerebellar regions in one case each. Despite the lack of reports describing the development of intradural chordoma, embryological study with three-dimensional reconstruction of the notochord revealed multiple forks with separated fragments at the rostral and caudal ends. It has been proposed that fragments of notochord may be left in the extradural region, from which intradural chordoma may originate. Intradural chordoma in the tentorium cerebelli may originate via migration of remnant notochord caused by early head trauma [

6].

Ecchordosis physaliphora (EP), which is a non-neoplastic condition in the intradural retroclival region, must be distinguished from intradural clival chordoma. EP is characterized by ectopic notochord tissue in the same location as intradural clival chordoma. Because the notochord lies in the clivus as a sigmoid shape, notochord can be left in the posterior surface of the clivus [

5]. EP is usually less than 2 cm in size, gelatinous in nature, and found in 2% of autopsies [

8]. EP and chordoma are histologically identical and difficult to distinguish by tumor location. However, EP is usually asymptomatic and hyperintense on T2WI, hypointense on T1WI, does not exhibit enhancement after gadolinium injection, and is pedunculated with the stalk attached to the clival surface. EP exhibits no neoplastic activity, no mitosis, and a very low MIB-1 count. EP presents with uniform cellular proliferation and without lobularity, mucin or necrosis [

5]. The Ki 67 index, the marker of cellular proliferation, is helpful for the differentiation of EP and chordoma [

4]. Also the Ki 67 index is associated with faster growing skull base chordomas. Our case is a negative expression for Ki 67 antigen in immunohistochemical stains. However, hypercellularity and nuclear atypia, which were consistent with chordoma than EP, is showed in the histopathological finding. The patient has the symptoms of headache and multiple cranial nerve palsies, and the large size mass above 2 cm and the heterogeneous enhancement with gadolinium were revealed in the imaging study. So, we could suggest the diagnosis of chordoma by pathological, clinical, and radiological findings.

The treatment of choice for classic intracranial chordoma is complete resection when possible. However, because of illdefined margins, extensive bony invasion, and adhesion to surrounding structures, chordomas may be difficult to remove completely. The treatment and prognosis of intradural chordoma have been reported in previous studies, and these studies indicate that intradural chordoma may be resected completely with good prognosis due to easy dissection from surrounding structures and absence of bony or dural invasion [

3,

5,

9]. After last follow-up, most cases do not exhibit recurrence. Recently, endoscopic methods that have better visualization for midline approaches have been reported to ensure good surgical modality and outcomes [

10]. In our case the chordoma was located in the midline, and we therefore chose a retrolabyrinthine transpetrosal approach to minimize distance by the mass and maximize the width of visualization. The mass was resected completely by this approach and remnant mass was not detected in immediate post-operative MRI. The last follow-up image taken at 12 months did not exhibit recurrence. In many reports, remnants of classic chordomas after surgical resection were treated with adjuvant radiotherapy. Previous studies indicate that radiotherapy is not effective for the treatment of remnant tumor. Therefore, other studies recommend repeat surgery. Recently, radiosurgery was recommended to treat remnant and recurrent chordoma as well as primary chordoma, although the length of follow-up has been insufficient. A case of radiosurgery used as adjuvant therapy for remnant intradural chordomas have been reported, which had good prognosis [

11].

Classic intracranial clival chordoma is associated with destruction of the clivus and calcification within the mass detected in CT scans. MRI shows high hyperintensity on T2WI, hypointensity on T1WI, and variable enhancement after gadolinium injection. In our case of intradural clival chordoma, except for the intact clivus, CT and MRI showed the same findings as classic chordoma. On pre-operative MRI, a cystic lesion was observed in the pons just behind the mass. The mass and cystic lesion was separated safely and the contacting pontine surface was found to be intact intraoperatively. The lesion was thought to represent intraparenchyme hemorrhage of the pons due to mass. It was absorbed and decreased in size, and that was confirmed at the last follow-up MRI.

In conclusion, intradural clival chordomas are different in nature from classic intracranial chordomas, and have welldefined margins, soft consistency, and lack of bone or dural involvement. EP, which originates from ectopic notochord in the same location as intradural chordoma and is non-neoplastic, should be differentiated from intradural clival chordoma by preoperative MRI. Intradural clival chordoma could be removed completely and is predicted to have a benign course and good surgical outcome.

Go to :