It is reported that intraorbital schwannomas account for 1-6% of all intraorbital tumors [

2]. The accurate diagnosis, using imaging modalities, of oculomotor schwannoma may be difficult because of the complex orbital anatomy and its low incidence. Two clues leading to diagnosis are tumor location along the course of the oculomotor nerve, and oculomotor nerve palsy on neurologic examination [

2,

4]. The most common symptom of oculomotor schwannomas is oculomotor nerve palsy, but oculomotor nerve palsy is not always the initial symptom [

4]. In the present case, optic nerve dysfunction was observed on neurologic examination without oculomotor nerve palsy. Thus, the optic nerve masses such as gliomas, schwannomas, or meningiomas appear to be differential preoperative diagnostic possibilities. However, we noted that the tumor origin was the oculomotor nerve during surgery. In patients with oculomotor schwannomas located in the intraorbital area without oculomotor nerve palsy, the operative finding may be important to confirm the tumor origin.

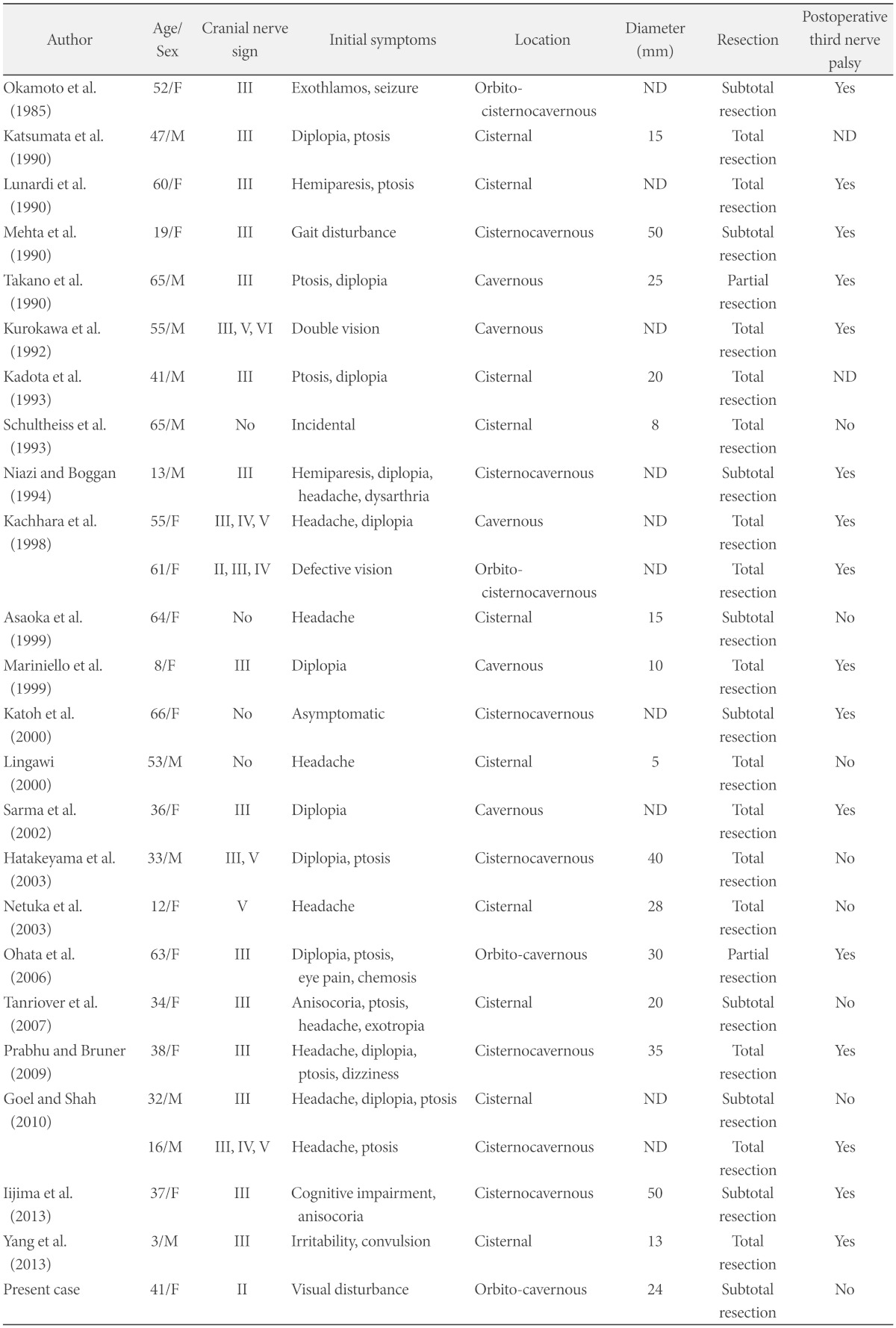

We reviewed 25 patients who received surgery for oculomotor nerve schwannomas (

Table 1). Preoperative oculomotor nerve palsy manifested in 19 cases out of 25, and optic nerve dysfunction was shown in only 2 patients, including the present case. The tumor extended to the orbit region in 4 cases, and 2 of 4 patients manifested optic nerve dysfunction. Regardless of the radicality of the resection, postoperative oculomotor nerve palsy occurred in patients with oculomotor schwannomas in the orbital region, excluding our case.

Table 1

Survey of oculomotor schwannomas treated by surgery in the literatures

Because of the tumor's benign property, total resection of the tumor is the treatment modality and adjunctive therapy is not needed. The oculomotor nerve is known to be fragile and is easily injured [

4]. Previous studies reported that total resection of the tumor results in complete oculomotor nerve palsy [

5,

6,

7]. Worsening of oculomotor nerve function may occur after subtotal or partial resection of the tumor [

2,

4]. The oculomotor nerve contains somatic motor fibers to many of the orbital muscles, but also carries parasympathetic fibers to the papillary muscle. Thus, oculomotor nerve palsy may worsen the patient's quality of life. It is difficult to decide on the best treatment strategy for oculomotor schwannomas. According to each case, several treatment strategies have been reported by researchers. Katoh et al. [

5] recommend 'wait-and-see' policy for asymptomatic patients with oculomotor schwannoma. According to Kim et al. [

8], Gamma Knife radio-surgery may be an effective and minimally invasive treatment modality without risk of cranial nerve palsy in treatment of patients with schwannomas originating from the oculomotor, trochlear, and abducence nerves. Radical resection inevitably results in worsened oculomotor function, almost invariably in complete palsy. Thus, Asaoka et al. [

4] recommend subtotal resection except large tumors that cause intractable symptoms. On the other hand, there were some reports of total resection of oculomotor schwannoma without permanent nerve palsy [

3,

9]. It's location influences the radicality of tumor resection. The chance of oculomotor nerve injury after surgical resection may increase as the resection proceeds more anteriorly toward the superior orbital fissure [

10]. In our review, past postoperative oculomotor nerve palsies occurred in all patients with tumors that extended to the orbital region, except our present case (

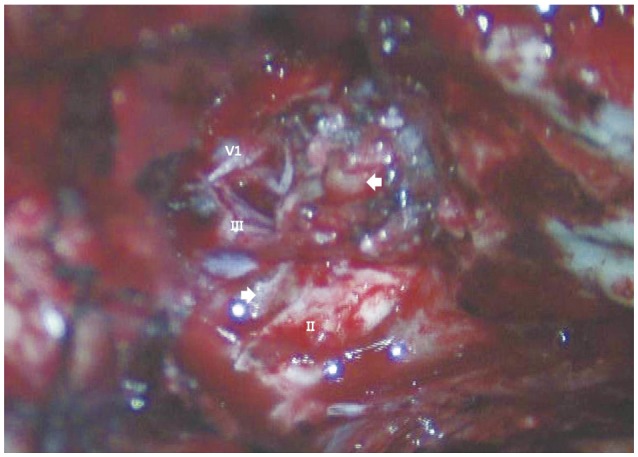

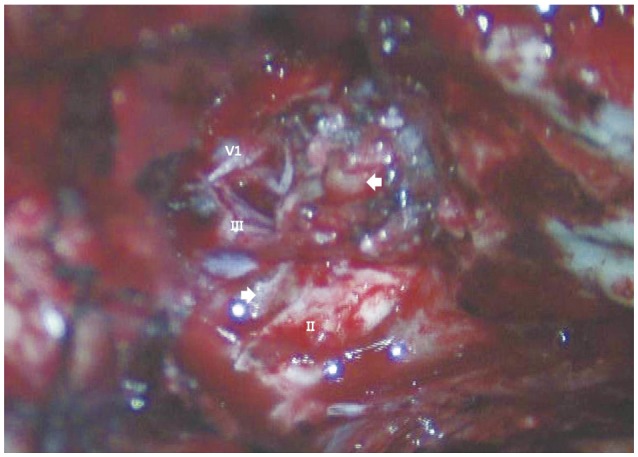

Table 1), where the tumor was located in the superior orbital fissure and close to other neurovascular structures. Also, the preoperative oculomotor nerve function was preserved. Thus, we decided to perform a subtotal resection to avoid complete oculomotor nerve palsy, and planned an adjuvant frameless radiosurgery for the remnant tumor. During the operation, most of the mass was removed leaving the tumor capsule. In the postoperative MRI, the target lesion could not be detected so we decided not to perform the adjuvant radiosurgery. There is no evidence of tumor recurrence on the one-year follow-up MRI, and we planned for follow-up MRI annually.

In conclusion, we report a case of oculomotor schwannoma in which the preoperative diagnosis may have been very difficult due to the complex orbital anatomy and the low incidence of disease. The treatment strategy should be established considering the preoperative nerve functions and the tumor location. We removed the tumor subtotally using the fronto-temporal approach with resulting temporary oculomotor nerve palsy.