Abstract

Sellar arachnoid cysts are rare; an infected arachnoid cyst is extremely rare as only one case has been reported to date in the literature. Here, we report a patient with an infected or inflamed sellar arachnoid cyst that was successfully treated with transsphenoidal surgery (TSA). A 53-year-old female with a history of chronic sinusitis developed a headache 5 months ago, and one month before admission polyuria, polydipsia, and abnormal vaginal bleeding occurred. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a sellar cystic mass with a thickened pituitary stalk. Preoperative hormonal study revealed normal pituitary hormone levels except for a moderate elevation of prolactin. She was diagnosed with diabetes insipidus of the central nervous system origin based on a water-deprivation test. TSA was performed under an impression of symptomatic Rathke's cleft cyst according to the MRI findings. Intraoperative findings showed confirmation of turbid intracystic contents, but micro-organisms were unidentified on microbial culture. Pathology of the cyst wall revealed inflamed meningoepithelial lining cells compatible with an arachnoid cyst.

An intracranial arachnoid cyst (AC) is a relatively common congenital lesion found in 0.2-1.7% of the population, including asymptomatic cases [1-3]. Furthermore, a symptomatic AC is rare especially among the elderly. AC is mainly distributed in the middle cranial fossa and cerebello-pontine angle, and is rarely diagnosed as intrasellar AC which accounts for 3% of intracranial AC [4] and 0.5% of pituitary lesions. Only 50 cases of sellar AC have been reported to date [5]. A PubMed search has revealed only one case of cerebral convexity AC infection mimicking symptoms of an epidural abscess, and this is the first reported case of a sellar AC, which induced symptoms from an infection. We describe the symptomatic inflamed, intrasellar AC case of a 53-year-old woman, who had ethmoid sinusitis and was treated using the transsphenoidal approach. Differential diagnosis and proper treatment of sellar cystic lesions, as well as the mechanism on how the AC induced symptoms are discussed.

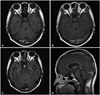

A 53-year-old female presented with headache of 5 months duration, and polydipsia, polyuria, and abnormal vaginal bleeding after menopause 1 month ago prior to the hospital visit with aggravation of the headache. No other specific medical history except chronic paranasal sinusitis was found. The magnetic resonance image (MRI) revealed a well-defined 9 mm sized cystic sellar lesion of iso-signal intensity on the T1 weighted image which was faintly enhanced on gadolinium enhancement (Fig. 1A, B). FLAIR image suggested the content of cyst was not cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) but high proteinous material, which was compatible with Rathke's cleft cyst (Fig. 1C). The enhanced sagittal image showed that the cyst was attached to the thickened pituitary stalk and displaced the pituitary gland inferiorly (Fig. 1D). She had been suffered from chronic paranasal sinusitis and all MR images and orbitomeatal computed tomography suggested inflammatory changes of the sinusitis. Trans-sphenoidal approach (TSA) was delayed for a week to see if the sinusitis was active.

Laboratory tests including blood chemistry and complete blood count were within normal limits, but the basal hormonal evaluation showed a mildly elevated prolactin (91.9 ng/mL). Adrenocorticotrophic hormone stimulation test revealed intact response of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis. Water deprivation test showed central type diabetes insipidus (DI), and the ophthalmologic examination revealed normal visual acuity and no visual field defects.

A transsphenoidal approach and cyst removal was performed under a diagnosis of Rathke's cleft cyst compressing the pituitary stalk based on MRI findings. Intraoperatively, the cyst fluid was turbid and the cyst wall was firmly stuck to the pituitary stalk.

We removed the cyst totally by separating from the pituitary stalk using a microscopic technique, but there was CSF leakage on the transitional zone of the Planum sphenoideum. We closed the leakage point with gelfoam, reconstructed the sellar floor with nasal septal bone, and transplanted autograft fat tissue into the sphenoid sinus. We performed a prophylactic lumbar drainage before the patient recovered from general anesthesia, and which was maintained for 3 postoperative days.

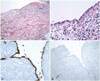

In the pathologic review, the inner layer of the cyst displayed a single layer of flattened meningoepithelial cells with a large amount of defected lesion; it was considered to be an AC rather than a Rathke's cleft cyst, and was accompanied by severe inflammation (Fig. 2).

There was no CSF leakage but aggravated diabetes insipidus was found during the immediate postoperative state. We confirmed that there was no CSF leakage by nasal endoscopy, and the lumbar drainage was removed 2 days after surgery. However, CSF leakage with posterior nasal drip presented 10 days after removal of the nasal packing. Thus, a lumbar drainage was performed with duraseal™ (Covidien, Waltham, MA, USA) sealant application to the operation site via a nasal endoscope. The patient was discharged two weeks later without CSF leakage and the same requirement of vasopressin administration was compared to the preoperative condition. The postoperative MRI at 3 months showed collapse of the cyst (Fig. 3). Basal hormone study was the same as preoperative levels including mild elevation of prolactin, and the patient still required vasopressin medication to control the DI up to the postoperative first year.

Most intrasellar ACs cause symptoms in up to 88% (45 of 55) of reported cases, which include headache, visual symptoms, weight gain, vertigo, confusion, irregular menstruation, and symptoms similar to those of non-functioning pituitary adenoma [5].

Sellar AC can be classified into the communicating type and non-communicating type according to the existence of communication with the suprasellar subarachnoid space, but there is no definite conclusion regarding the pathophysiology and development mechanisms [6]. In patients with sellar ACs extending to the suprasellar area, the mechanism of causing symptoms is presumed to be trapped CSF in the cyst by a ball-valve mechanism [5,7]. As the sellar AC expands and press the surrounding normal structures, symptoms are elicited.

Infection of the AC may be one of the mechanisms causing symptoms in the patients. A case was reported which described an AC in the cerebral convexity that was infected and caused pressure symptoms. An 83-year-old woman with pneumonia presented with rapidly developing hemiparesis and seizure. Pus was found in the operation field and the wall membrane was confirmed as inflamed AC [8]. In our case, we assumed that chronic maxillary sinusitis may have caused infection of the sellar AC, as we did not have a proof of direct extension from the sphenoid sinus to the sellar lesions. However, the turbid content in the cyst revealed during the operation as well as inflammatory change of the cyst wall found in the pathology support the secondary inflammation of the AC. Accordingly, this case is only the second report of symptom-causing AC due to an infection, and the first report of a pathologically proven infected sellar AC.

Representative intrasellar cystic lesions are craniopharyngiomas, Rathke's cleft cysts or arachnoid cysts, which are hardly distinguished by pure radiologic and/or clinical findings [9]. Shin et al. [9] have reported the radiologic and clinical findings of pituitary cystic lesions: among their 56 operated lesions, all the arachnoid cyst are cystic lesions and calcification was not found in the ACs unlike craniopharyngiomas and Rathke's cleft cysts.

Both TSA and craniotomy may be applied for the surgical treatment of intrasellar AC. We considered TSA as an appropriate surgical approach in this case because suprasellar extension was not marked and the cyst was relatively small in size. Miyamoto et al. [10] suggested that making a full fenestration with the cisternal space is important for the surgical treatment of intrasellar ACs. In addition, they recommended not to open the roof of the cyst, if possible, since complications due to CSF leakage may occur in TSA surgery, and excision of the cyst wall via craniotomy is appropriate for a large sellar AC. On the other hand, Dubuisson et al. [5] have said that TSA is the treatment of choice for intrasellar ACs despite the risk of CSF fistulae. They insisted that the CSF leakage may be prevented if the sellar floor is closed up hermetically followed by a fat packing of the sphenoid sinus with preventive lumbar drainage.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Preoperative MR images. Axial T1 non-enhanced (A) and gadolinium enhanced (B) images show a well-defined intrasellar cystic lesion, and the wall is faintly enhanced. FLAIR image suggested the content of cyst was not CSF but high proteinous material, which was compatible with Rathke's cleft cyst (C). Enhanced sagittal image showed that the cyst was attached to the thickened pituitary stalk and displaced the pituitary gland inferiorly (D). MR: magnetic resonance, CSF: cerebrospinal fluid, FLAIR: fluid attenuated inversion recovery.

Fig. 2

Photomicrograph of the cyst. The inner layer of the cyst wall shows a single layer of flattened meningothelial cells and the outer layer is composed of collagenous tissue, slightly thickened by mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltration and edema (hematoxilin and eosin; A: ×100, B: ×200). The immunohistochemical stains of the lining cells of the cyst are positive for epithelial membrane antigen (C) and negative for glial fibrillar acidic protein (D), which is consistent with an arachnoid cyst. There is no glial tissue in the outer layer of the cyst (×200).

References

1. Eskandary H, Sabba M, Khajehpour F, Eskandari M. Incidental findings in brain computed tomography scans of 3000 head trauma patients. Surg Neurol. 2005; 63:550–553. discussion 553.

2. Katzman GL, Dagher AP, Patronas NJ. Incidental findings on brain magnetic resonance imaging from 1000 asymptomatic volunteers. JAMA. 1999; 282:36–39.

3. Weber F, Knopf H. Incidental findings in magnetic resonance imaging of the brains of healthy young men. J Neurol Sci. 2006; 240:81–84.

4. Rengachary SS, Watanabe I. Ultrastructure and pathogenesis of intracranial arachnoid cysts. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1981; 40:61–83.

5. Dubuisson AS, Stevenaert A, Martin DH, Flandroy PP. Intrasellar arachnoid cysts. Neurosurgery. 2007; 61:505–513. discussion 513.

6. Miyajima M, Arai H, Okuda O, Hishii M, Nakanishi H, Sato K. Possible origin of suprasellar arachnoid cysts: neuroimaging and neurosurgical observations in nine cases. J Neurosurg. 2000; 93:62–67.

7. Rohrer DC, Burchiel KJ, Gruber DP. Intraspinal extradural meningeal cyst demonstrating ball-valve mechanism of formation. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1993; 78:122–125.

8. Sivaraman V, Au-Yeung A, Brew S, McEvoy AW, Greenwood R. An infected arachnoid cyst in an elderly patient. J Neurol. 2008; 255:1088–1089.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download