Abstract

Pituitary apoplexy is a rare but life-threatening disorder. Clinical presentation of this condition includes severe headaches, impaired consciousness, fever, visual disturbance, and variable ocular paresis. The clinical presentation of meningeal irritation is very rare. Nonetheless, if present and associated with fever, pituitary apoplexy may be misdiagnosed as a meningitis. We experienced a case of pituitary apoplexy masquerading as a meningitis. A 42-year-old man presented with meningitis associated symptoms and initial imaging studies did not show evidence of intra-lesional hemorrhage in the pituitary mass. However, a follow-up imaging after neurological deterioration revealed pituitary apoplexy. Hereby, we report our case with a review of literatures.

Pituitary apoplexy is a rare, but life-threatening disorder that usually results from intratumoral hemorrhage or infarction in pituitary adenomas [1]. The clinical manifestations of pituitary apoplexy generally include acute headache, impaired consciousness, vomiting, visual impairment, and ophthalmoplegia [2]. However, signs of meningeal irritation are not typical findings [3]. Therefore, the presence of meningeal irritation may lead to misdiagnosis as a case of meningoencephalitis or spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage, and delay in the proper management of the disease. Hereby, we report a case of pituitary apoplexy with an initial presentation mimicking meningitis, with a review of the related literatures.

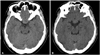

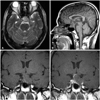

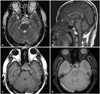

A 42-year-old man visited the emergency unit of our hospital with sudden onset of headache and vomiting. He had a past medical history of hypertension and chronic renal failure that were controlled with regular medication. On physical examination, there were no positive signs suggesting intracranial infections or cerebrovascular accident. Vital signs including body temperature were normal. Neurological examination showed alert mentality with a Glasgow coma scale of 15 (E4, V5, M6) and without cranial nerve palsies. The patient's ocular motion and visual field were normal. Serological analysis revealed normal range of white blood cell count (6,900/µL, neutrophil 70.6%), erythrocytes sedimentation rate (ESR, 7 mm/hr), and C-reactive protein (CRP, 0.07 mg/dL). Urgent noncontrast brain computed tomography (CT) scan showed no intracranial hemorrhage or other abnormal findings, except for a sellar mass extending into the suprasellar area (Fig. 1). Contrast enhancement CT scan was not done because of the patient's chronic renal failure. Sellar magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a pituitary mass with suprasellar extension, which was partially enhanced at the periphery of the tumor (Fig. 2). A complete analysis of the pituitary hormones revealed decreased serum cortisol level (1.5 µg/dL at 8:00 A.M., 1.4 µg/dL at 4:00 P.M.). Cortisone substitution was immediately started (dexamethasone intravenously, 10 mg per 6 hours). However, a 38.4℃ fever developed 30 hours after the onset of headache with marked neck stiffness. Serological analysis was repeated, which revealed increased ESR (11 mm/hr) and CRP (5.30 mg/dL) compared to initial results. Because his symptoms and signs suggested meningeal irritation, our initial diagnosis was an infectious meningoencephalitis with an incidental pituitary tumor rather than an overt pituitary apoplexy. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was examined through a lumbar puncture. The opening pressure was 26.5 cm H2O and CSF analysis revealed an increased leukocyte count (260/µL) with 88% neutrophilic granulocytes, and increased total protein content (87 mg/dL) and red blood cell count (290/µL). The sugar content of the CSF was found to be 57 mg/dL and the blood sugar level was 99 mg/dL. Based on the laboratory results and the symptoms of the patient, empirical antibiotics (vancomycin, ceftriaxone, and ampicillin) therapy was started via an intravenous route for the treatment of suspected bacterial meningitis before the confirmation of the CSF culture study. After administration of antibiotics, his fever subsided. On admission day 3, follow-up CSF analysis was done through another lumbar puncture. The opening pressure had improved to 18 cm H2O. CSF examination showed improvement of the suspected meningitis. The leukocyte count was 30/µL with 30% neutrophilic granulocytes and the total protein content was 68 mg/dL. The sugar content of the CSF was 91 mg/dL and the blood sugar level was 266 mg/dL. However, the sudden development of incomplete ptosis and medial gaze limitation of the left eye was noted. Also bitemporal hemianopsia was observed in the visual field examination. A follow-up MRI was performed and showed certain findings compatible with an intratumoral hemorrhage of the pituitary mass, in comparison with the initial MRI (Fig. 3). Based on the follow-up MR imaging and neurological changes, the patient was diagnosed as with pituitary apoplexy. We determined to perform an emergency decompressive surgery because of the progressive worsening of the patient's oculomotor nerve palsy. A transsphenoidal approach was initiated and we observed necrotic tissue mixed with blood clots inside the sellar mass. The tumor was completely removed. The pathological diagnosis was confirmed as pituitary adenoma with apoplexy (Fig. 4). The patient's headache, oculomotor nerve palsy and visual field defect began to improve immediately after surgery. Preoperative CSF culture study reported no cultured microorganisms, and the postoperative follow-up CSF analysis showed normal findings. The patient was discharged on day 14 without any neurologic deficits.

Pituitary apoplexy was first described by Brougham et al. [4] at 1950. The prevalence of pituitary apoplexy reported in the literature is variable and ranges from 0.6% to 27.7% [5]. Predisposing factors have been identified in approximately 25% of pituitary apoplexy. Head trauma, bromocriptine administration or withdrawal, anticoagulation, or cardiac bypass has been cited as inciting apoplectic episodes [6]. However, most pituitary apoplexies are considered to have idiopathic etiologies. The usual clinical manifestations of pituitary apoplexy include sudden onset headaches, vomiting, mental deterioration, ophthalmoplegia, and visual field defects. The meningeal irritation signs are rare and not typical findings. However, the presence of meningeal irritation signs and fever in some cases of pituitary apoplexy has been documented in the past literature [7,8]. In cases suspected as meningoencephalitis, CSF analysis has been regarded as a confirmative study. However, CSF study may not be helpful in distinguishing pituitary apoplexy from meningoencephalitis, since chemical meningitis may have resulted from leakage of blood or necrotic tissue into the subarachnoid space [2,9]. In our case, the sugar content of the first CSF analysis was not low enough to suggest bacterial meningitis and no microorganism was cultured. Therefore, we were able to conclude that the abnormal findings of CSF examination were attributed to chemical meningitis.

Neuroimaging studies allow meticulous characterization of the extent of necrosis and/or hemorrhage, and the relationship of hemorrhage and denuded tissue to neurovascular structures in addition to a diagnosis of pituitary apoplexy. Brain CT scans may reveal the hyper-density of acute hemorrhage, or demonstrate the mixed density of acute blood and hypodense necrotic tissue within the lesion in the sellar or suprasellar areas. Subarachnoid hemorrhage may be evident if blood has invaded the basal cisterns. The greater sensitivity, precision, and tissue definition of MR imaging usually reveal the heterogeneous intensity of hemorrhage, edematous pituitary gland, and necrotic tumor, leading more readily to a diagnosis of pituitary apoplexy [10]. However, in this patient, the initial non-contrast brain CT after presentation of symptoms did not show any evidence of intra-tumoral or subarachnoid hemorrhage. Also, there were no definite findings which suggested the presence of an intra-lesional hemorrhage in the first sellar MR study. Therefore, we initially suspected the etiology to be meningitis and made a misdiagnosis. After pathologic confirmation of the pituitary apoplexy, we retrospectively reviewed again the brain CT and MRI findings. Non-contrast CT images and non-contrast T1-weighted (T1W) images of the initial MRI did not show any typical findings compatible with an intratumoral hemorrhage. However, the contrast enhancement T1W coronal image showed peripheral enhancement of the mass, which should have been suggestive of a tumor infarction. These initial MRI findings may have suggested that a pituitary apoplexy was in the early stage and in progress when the patient visited the hospital. Although our routine sellar MR protocol does not include gradient-echo T2-weighted images which are sensitive to hemorrhages, we overlooked these MR findings. This subsequently led to a delay in the correct diagnosis until a follow-up MRI showed findings compatible with pituitary apoplexy.

According to our experience and review of literatures, neuroimaging studies may not reveal typical findings compatible with a pituitary apoplexy in the very early stages, and meningeal irritation signs may be the presenting symptoms. Therefore, we suggest that pituitary apoplexy should be included as one of differential diagnoses in patients who present with meningeal irritation signs and a pituitary tumor, although the initial neuro-imaging studies did not show typical findings. Careful neurological monitoring and serial imaging follow-up would be useful to make a correct diagnosis.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Non-contrast brain computed tomography scans show a 2.0×1.5 cm sized isodense sellar mass (A), without evidence of intralesional or subarachnoid hemorrhage (B). |

| Fig. 2Initial sellar magnetic resonance imaging findings. T2-weighted axial image shows a sellar mass with heterogenous internal high intensity signals (A). Non-contrast T1-weighted sagittal and coronal images show a pituitary mass extending suprasellar area without typical findings compatible with intralesional hemorrhage (B and C) and contrast enhanced coronal image show a pituitary mass with peripheral enhancement (D). |

| Fig. 3Follow-up brain magnetic resonance imaging findings. T2-weighted axial image shows mixed signal intensity of pituitary mass (A). Non-contrast T1-weighted sagittal and axial images show peripheral high signal intensity of pituitary mass (B and C). Gradient-echo T2-weighted axial image shows multiple low signal intensities suggesting intralesional hemorrhage (D). |

| Fig. 4Histopathologic findings from specimens of the pituitary tumor. Hematoxylin and eosin staining is demonstrating the hemorrhagic necrosis of pituitary gland consistent with pituitary apoplexy (A: ×10 magnification) and pituitary adenoma showing necrotic degeneration with hemorrhage (B: ×200 magnification). |

References

1. Tsitsopoulos P, Andrew J, Harrison MJ. Pituitary apoplexy and haemorrhage into adenomas. Postgrad Med J. 1986; 62:623–626.

2. Verrees M, Arafah BM, Selman WR. Pituitary tumor apoplexy: characteristics, treatment, and outcomes. Neurosurg Focus. 2004; 16:E6.

3. Nawar RN, AbdelMannan D, Selman WR, Arafah BM. Pituitary tumor apoplexy: a review. J Intensive Care Med. 2008; 23:75–90.

4. Brougham M, Heusner AP, Adams RD. Acute degenerative changes in adenomas of the pituitary body--with special reference to pituitary apoplexy. J Neurosurg. 1950; 7:421–439.

5. Randeva HS, Schoebel J, Byrne J, Esiri M, Adams CB, Wass JA. Classical pituitary apoplexy: clinical features, management and outcome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1999; 51:181–188.

7. Cagnin A, Marcante A, Orvieto E, Manara R. Pituitary tumor apoplexy presenting as infective meningoencephalitis. Neurol Sci. 2012; 33:147–149.

8. Huang WY, Chien YY, Wu CL, Weng WC, Peng TI, Chen HC. Pituitary adenoma apoplexy with initial presentation mimicking bacterial meningoencephalitis: a case report. Am J Emerg Med. 2009; 27:517.e1–517.e4.

9. Bjerre P, Lindholm J. Pituitary apoplexy with sterile meningitis. Acta Neurol Scand. 1986; 74:304–307.

10. Dulipsingh L, Lassman MN. Images in clinical medicinePituitary apoplexy. N Engl J Med. 2000; 342:550.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download