Abstract

Objective

Despite successful efforts to shorten the door-to-balloon time in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), pre-hospital delayremains a problem. We evaluated the factors related to pre-hospital delay using the Jeonbuk regional cardiovascular center database.

Methods

From 2010 to 2013, a total of 384 STEMI patients were enrolled. We analyzed the onset time, door time, and balloon time, and the patients were grouped according to pre-hospital delay (120 minutes). Clinical and socio-demographic variables were compared.

Results

53.2% of patients had prolonged onset-to-door time (median 130, interquartile range [IQR] 66~242 minutes), and 68.5% of patients did not achieve <120 minute of total ischemic time (median 175, IQR 110~304 minutes). Pre-hospital delay was more frequent in patients with old age, female, no local residence, low education level, transfer via other hospital and no use of emergency squad (119). Only 20% of patients used 119, and 119 team responded in a prompt manner (call to scene time 6 min), but 41.6% of patients was transported to non-PCI-capable hospitals. Multivariate analysis revealed that transfer via other hospital [Odds ratio (OR) 2.5, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.6-4.1, p<0.001), use of 119 (OR 0.4, 95% CI 0.2-0.6, p<0.001), age >60 years (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.1-3.0, p=0.031) and hypertension (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.2-2.9, p=0.047) were independent predictors of pre-hospital delay.

Figures and Tables

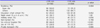

Table 1

Baseline clinical and angiographic characteristics according to pre-hospital delay

Table 2

Socio-demographic characteristics according to pre-hospital delay

Table 3

Status of 119 responses

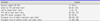

Table 4

Multivariate analysis for the prediction of pre-hospital delay

References

1. Gersh BJ, Stone GW, White HD, Holmes DR Jr. Pharmacological facilitation of primary percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction: is the slope of the curve the shape of the future? JAMA. 2005; 293:979–986.

2. O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE Jr, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013; 127:e362–e425.

3. Jeong MH. Can time delay be shortened in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction?: experience from Korea acute myocardial infarction registry. Korean J Med. 2010; 78:582–585.

4. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, Jaffe AS, Apple FS, Galvani M, et al. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2007; 28:2525–2538.

5. Terkelsen CJ, Sørensen JT, Maeng M, Jensen LO, Tilsted HH, Trautner S, et al. System delay and mortality among patients with STEMI treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA. 2010; 304:763–771.

6. Jeong JO, Kim YC, Sung BY, Kim JK, Jeong JY, Lyu JG, et al. Analysis of time delay to affect thrombolytic therapy in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Korean Circ J. 1997; 27:842–850.

7. Kim JA, Jeong JO, Ahn KT, Park HS, Jang WI, Kim MS, et al. Causative factors for time delays in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Korean J Med. 2010; 78:586–594.

8. Park YH, Kang GH, Song BG, Chun WJ, Lee JH, Hwang SY, et al. Factors related to prehospital time delay in acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Korean Med Sci. 2012; 27:864–869.

9. Lee JH, Jeong MH, Rhee JA, Choi JS, Park IH, Chai LS, et al. Factors influencing delay in symptom-to-door time in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Korean J Med. 2014; 87:429–438.

10. Meischke H, Ho MT, Eisenberg MS, Schaeffer SM, Larsen MP. Reasons patients with chest pain delay or do not call 911. Ann Emerg Med. 1995; 25:193–197.

11. Thuresson M, Jarlöv MB, Lindahl B, Svensson L, Zedigh C, Herlitz J. Factors that influence the use of ambulance in acute coronary syndrome. Am Heart J. 2008; 156:170–176.

12. Johansson I, Strömberg A, Swahn E. Ambulance use in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2004; 19:5–12.

13. Herlitz J, Hartford M, Aune S, Karlsson T, Hjalmarson A. Delay time between onset of myocardial infarction and start of thrombolysis in relation to prognosis. Cardiology. 1993; 82:347–353.

14. Mathews R, Peterson ED, Li S, Roe MT, Glickman SW, Wiviott SD, et al. Use of emergency medical service transport among patients with ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: findings from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry Acute Coronary Treatment Intervention Outcomes Network Registry-Get With The Guidelines. Circulation. 2011; 124:154–163.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download