Abstract

Rabies is an important zoonosis in the public and veterinary healthy arenas. This article provides information on the situation of current rabies outbreak, analyzes the current national rabies control system, reviews the weaknesses of the national rabies control strategy, and identifies an appropriate solution to manage the current situation. Current rabies outbreak was shown to be present from rural areas to urban regions. Moreover, the situation worldwide demonstrates that each nation struggles to prevent or control rabies. Proper application and execution of the rabies control program require the overcoming of existing weaknesses. Bait vaccines and other complex programs are suggested to prevent rabies transmission or infection. Acceleration of the rabies control strategy also requires supplementation of current policy and of public information. In addition, these prevention strategies should be executed over a mid- to long-term period to control rabies.

Rabies is an important zoonosis in the public health and veterinary arenas. It can infect all warm-blooded animals, which includes humans, and it is distributed worldwide [1]. In particular, when a human is infected, it is termed "hydrophobia." Rabies virus that belongs to the genus Lyssa of the family Rhabdoviridae is bullet-shaped. Four strains have been reported and it mainly multiplies in nerve tissue, the salivary glands, and cornea epithelium cells. Rabies causes central nervous system disease, including various nervous symptoms and encephalitis. The lethal ratio in a single outbreak is almost 100%. It is classified as a class 2 livestock infectious disease in South Korea and as a reportable disease by the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) [2].

Rabies occurs in 2 different epidemiologic forms: urban rabies, for which domestic dogs act as the main carrier and transmitter, and sylvatic (wild type) rabies, with different wildlife species such as the fox and raccoon dog acting as carriers and/or transmitters. Raccoon dogs are the main carriers and transmitters of sylvatic rabies, which, according to epidemiologic outbreak records, comprise a large proportion of infection in Korea. Analysis has permitted us to determine that it changed from the urban to wild type due to the development and provision of vaccines and control methods [3].

Rabies is a high-mortality zoonosis, but is easily prevented by animal vaccination. An injection vaccine can be used as management for livestock or pets, which may be the case. However, inoculation of all target animals with the injected vaccine would be quite difficult in wild animals. Wild animals with high rabies susceptibility are the fox, coyote, jackal, and wolf; low rabies susceptibility animals include the skunk, raccoon dog, bat, and mongoose. The low-susceptibility animal functions as a carrier and spreads the virus. Thus, the raccoon dog is the main wild animal of concern in relation to rabies infection of livestock in Korea. There is a greater need for research into updating of the rabies control system [4].

The aim of this research was to prevent rabies outbreak effectively, finally eliminating the infection from domestic animals. We also attempted to identify weaknesses in the existing rabies control strategy, and finally propose a new control strategy model that addresses existing weaknesses. First, this research analyzed a rabies outbreak and searched for weaknesses in the current rabies control system. Second, we collected various effective control strategies, data, and the policies of other governments, and proposed a mid- to long-term plan for an effective rabies control strategy.

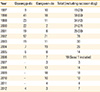

The first report of rabies was in 1907; since then, 200-800 cases were reported every year and it occurred continuously until 1945. Since then, 3-91 cases occurred per year until the 1970s. Subsequently, outbreak increased every year; in 1984, there was only 1 case; following the institution of the vaccination program and abandoned dogs prevention policy by the government, there was no outbreak until 1992. However, in September 1993 in Gangwon-do and Cheorwon-gun, rabies occurred in dogs and occurred continuously every year. Recently, 2 cases in dogs, 1 case in a cow, and 4 cases in raccoon dogs were confirmed in 2012; there have been 2 cases (cat and cow) and 4 cases (dog) in 2013. Rabies occurred more frequently in January, November, December, February, and April; the highest frequency according to seasonal outbreak was in the winter (December to February) (Table 1) [5].

In the 1960s, there were nationwide rabies outbreaks; in the 1970-1980s, rabies occurred in most of the regions except in Chungcheongnam-do and Jeju. In 1993, there were cases in Gangwon-do and Cheorwon-gun, which is in proximity to the military border, and in regions such as Gyeonggi-do, Yeoncheon-gun, Paju-si, and Pocheon-si. Outbreak was more frequent in regions such as Gangwon-do, Inje-gun, Yanggu-gun, and Cheorwon-gun. After 2002, rabies tended to occur in the northern regions of Gangwon-do (29 cases in Goseong-gun) and Gyeonggi-do (27 cases in Yeoncheon-gun, 25 cases in Paju-si, and 25 cases in Yangju-si). In 2005, there was continuous outbreak: 2 cases from Gimpo-si, the southern area of the Han River, and 1 case from Yangpyeong-gun [6].

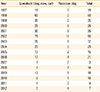

Recently,wild raccoon dogs moved to new habitats due to development of an industrial complex in the Sihwa Lake region, Hwaseong-si, Gyeonggi-do. These movements increased the possibility of contact with rabies-infected animals and transmission of rabies infection to other animals or humans.In fact, after 2 cases (raccoon dog) in Goyang-si, Gyeonggi-do and 1 case in Eunpyeong-gu, Seoul (raccoon dog) in 2006, the outbreak of the rabies after 7 years in 2012 in Suwon-si and Hwaseong-si, Gyeonggi-do was significant because rabies was considered to have "escaped" from the rural and mountain areas and transmitted to high-population urban areas (Table 2) [7].

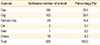

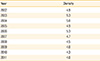

In domestic outbreak, rabies usually occurred in cows, dogs, and raccoon dogs. There was a clear tendency for the increase or decrease of outbreak to be similar in cows and dogs. In farms that bred both cows and dogs, rabies was detected in both species. Since 1997, the year the government began investigating rabies infection in wild animals, the raccoon dog was assumed to be the main transmitter of rabies to breeding live stock (Table 3) [7].

Hydrophobia was entered into official records from 1962; the first outbreak was a case in 1984. Before 1999, there were no reports of hydrophobia in humans in Korea. The aspect of outbreak between hydrophobia in humans and rabies in animals was not directly proportional. However, their epidemiologic characters shared considerable similarity, and geographic analysis also revealed similarities in their outbreak [8].

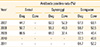

Immune serum therapy and vaccination enabled the prevention of hydrophobia in a person who had been bitten by an infected animal. However, there were reports of death in people who did not undergo treatment after being bitten. Hydrophobia, which occurred continuously, was not reported from 2004 until 2013 (Table 4) [1,2].

Rabies, which mainly occurred in areas close to the military demarcation line, exhibited a tendency to move south over time. The rabies control strategy required remodeling because the rabies outbreak had changed. It was known that the outbreak of rabies had moved gradually to urban areas (high-population areas) as compared to the past, where rabies mainly occurred in rural areas (low-population areas).

Analysis of species outbreak determined that it mainly infected in cows, dogs, and raccoon dogs, and it was presumed that the main transmitter in the Gyeonggi-do and Gangwon-do regions was the raccoon dog. According to seasonal outbreak, distribution was most frequent in the winter. There was also outbreak in the spring, autumn, and summer, in that order. Consensus was that this was when the raccoon dog, the main rabies transmitter, was most active [9].

Analysis of rabies outbreak location and environmental terrain condition found that about 85% of the places where the rabies occurred were the foot of mountains, valleys, and around rivers, which were areas where contact possibility with wild animals was high. Raccoon dog habits such as fishing and territorial range appeared to support this.

Rabies can be prevented by vaccination. The application of focused vaccination to dogs and cows is important. The government supports the annual supply of rabies vaccine under the Livestock Disease Prevention Plan. Governors around the country assign quantities of rabies vaccine supply according to the situation of rabies outbreak in livestock. Mayors and heads of district order vaccinations and provide public information under the Prevention of Contagious Animal Diseases Act. The government appoints a veterinary hospital to provide vaccinations, or direct vaccinations of livestock are undertaken by vaccination agents (veterinary inspectors, public veterinarians, vaccination assistants). Subsequently, the government issues a certificate of vaccination to the owner (Table 5) [10].

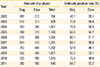

Rabies serum analysis has been performed on a number of dogs and cows from the Si, Gun, and nearby Si and Gun areas in Gangwon-do and Gyeonggi-do every year from 2002. Blood collection was carried out through a cooperative effort between the Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency and the Livestock Disease Prevention Agency. The agents visit each farm directly and collect blood from the animals. Serum analysis is performed using a neutralizing peroxidase-linked assay by the Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency (Tables 6, 7).

Transmission of rabies is influenced by the population density of susceptible animals in the area [11]. Depopulations of suspected animals have been used to decrease number of outbreak of the disease. However, there was low efficiency in many cases because wild animal populations were resilient. For example, foxes were culled, or hunted in Europe in the past, however this did not decrease the population of fox and the number of outbreak of rabies. The method including decreasing of susceptible animal population and vaccination in parallel was executed from 1999 in Canada and it was effective on reducing rabies outbreak in raccoon dogs [12].

To prevent rabies, the bait vaccine, an oral vaccine has been developed. Since Switzerland applied the bait vaccine for the first time in 1978, it has been considered an effective method and used in multiple European nations [13]. To achieve optimal vaccination result, vaccination time, coverage area for vaccination, effective method for bait scattering and potential number of wild animals should be considered. The years of when each country has been started to apply the vaccine are as follows: Switzerland (1982), Germany (1983), Italy (1984), Austria, Belgium, France, Luxembourg (1986), and Finland, the Republic of Czechoslovakia (1988), Canada (1989), the United States of America (1991), and the Republic of Korea (2001) [14]. The United States of America defined their bait vaccine scattering area to intercept rabies caused by the raccoon dog. In Europe, application of the bait vaccine resulted in the successful extermination of rabies from the Netherlands, Italy, Switzerland, France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Republic of Czechoslovakia [12].

Before 1975, when a person was bitten by a wild animal suspected of having rabies, immunotherapy was used to inhibit replication of the virus, the number of incidences in Alaska, USA, was 104.8 per 100,000 people every year. From 1975, the Alaskan government initiated a project for comprehensive rabies prevention with cooperation of the medical health, veterinarian public health, and livestock departments. The key concept of this project was improvement of the rabies vaccination coverage and electronic management of vaccination records. Despite the fact that wild animals were important transmitters of rabies infection, dogs were more common transmitter in human infection caused by bites. Comparing the aspects of disease prevention management, dogs were more manageable than wild animals. Certain programs to improve the rabies vaccination coverage were carried out in the rural regions, which had low accessibility to veterinary public service. First, the government supplied rabies vaccine by establishing a budget in the state public health department. Second, the owner paid only the vaccination fee if vaccination was performed at a private veterinary clinic. Third, the government educated and trained lay vaccinators to vaccinate animals without charge in regions with low accessibility to clinics. These veterinarians or vaccinators reported to the government and managed the vaccination records [15].

At March 1997, the first outbreak of raccoon dog rabies in Ohio, Mahoning occurred, and then number of rabies outbreak rapidly increased. After 1997, the government carried out a complex program that linked the bait vaccine scattering project, the wild raccoon dog capture and analysis program, rabies diagnosis program of infection-suspected animals, and a public information plan. In 2000, there was no report of raccoon dog rabies. After 2001, 1-2 cases of raccoon dog rabies were reported from around the border with Pennsylvania within a 1.6-km area every year. With the cooperation of nearby states, the state government established a bait vaccine zone (buffer zone) to prevent the spread of rabies. It prevented the spread of raccoon dog rabies from Pennsylvania, which was a rabies outbreak area, West Virginia, and Virginia, to Ohio, which is in the west, Kentucky, and Tennessee injection [11,16].

Ontario, Canada, which possesses a vast natural area, adopted the main strategy of a rabies prevention plan based on research on wild animals. Rabies outbreak in red fox and skunks in the eastern and southwest parts of Ontario was a problem. After development of a bait vaccine suitable for wild animals, the vaccine was distributed via air scattering using aircraft. From 1992, rabies was almost eradicated in this area as a result of the program. The state also had a rabies research unit under the Ministry of Nature and Resource to protect wild animals from wild-type rabies. This unit monitored worldwide outbreaks of rabies and analyzed type of rabies viruses isolated from brain samples of rabies-positive animals in various countries. Urban areas such as Toronto adopted the trap-vaccinate-release (TVR) method as a rabies protection plan. Wild animals were trapped, vaccinated, and released to same area where they were caught. According to statistical records, 60-70% of skunks and raccoon dogs that lived in urban areas were vaccinated from 1987 to 1992. The border between Canada and the United States of America contained a disease prevention area in which a combined vaccination plan that included bait vaccine scattering and TVR was executed. The rabies infection situation was monitored through analysis of wild animal corpses within these areas under international cooperation between the United States of America and Canada [12,17].

The Bavarian model that was initially used in the Bavaria region of Germany was used to prevent fox rabies. This program was performed by hunters who volunteered. Each hunter was charged with one sector on the map. They scattered the bait vaccine in the sector to be ingested by the target animal. After scattering the bait vaccine, the hunters monitored whether the vaccine was ingested. Lastly, serum antibody analysis was performed to estimate the antibody-positive rate of the target animal. Subsequently, many European countries used this method for rabies prevention campaigns and produced good results for rabies prevention [18].

Rabies prevention using the bait vaccine in Belgium was executed initially in 1986. Before the bait vaccine was instituted, there were >500 rabies cases every year. 2 years after using the bait vaccine, the outbreak of rabies decreased by around 50%. However, there were 515 and 842 cases in 1989 and 1990, respectively. This was the highest number of outbreaks since 1983. To decrease rabies outbreak, a 30-km bait vaccine scattering area (buffer zone) was established, and then expanded to 50-70 km. According to an investigation that compared the rabies antibody-positive rate of the red fox in 1994, the average antibody-positive rate of animals living in the area where the bait vaccine had been scattered was 25-86%. Bait vaccine aerial scattering was carried out in March and July, and in the fall in 1995; the scattering quantity was 15.7-17.2/km2, and an additional 5 bait vaccines were scattered near every red fox habitat. The entire scattering area spanned 8,700 km2, but 213 rabies cases occurred. Bait vaccine scattering was not carried out in France and the German border area; it required an international cooperative effort. To confirm bait vaccine intake, 15 foxes per 100 km2 were analyzed. The scattering method was similar to that used in 1996, but increased quantities of the bait vaccine were used. Tetracycline analysis of the animals' teeth revealed that the number of animals that took up the bait vaccine had increased. After 1998, rabies did not occur in red foxes; the last outbreak of rabies, which occurred in a cow, was in 1999. From 1966 to 2000, approximately 7,000 of 29,000 samples were rabies-positive, among which around 4,000 cases were related to red foxes. According to the OIE data, Belgium was classified as a rabies non-outbreak nation after 2001 [19].

The bait vaccine method is known as a proper effective plan among several presented rabies prevention methods. The approach had high efficiency with small input as compared to other plans. There are some weaknesses to the bait vaccine, which can be observed in current rabies prevention strategy [17].

The most important element for the determination of bait quantity was the density of the wild raccoon dog, which was the target animal. The major reason that rabies occurred continuously in Gangwon-do and did not occurred for several years in Gyeonggi-do is the insufficient supply of bait vaccine as compared with the demand. Gangwon-do has a high density of raccoon dogs and a higher proportion of mountain terrainas compared with Gyeonggi-do, but the determination of the bait vaccine quantity did not consider these points. Currently, such points are considered and supply follows the raccoon dog density. However, there still appears to be insufficient supply of bait vaccine when the actual condition of each local government is considered. As this supply quantity short fall is compensated by additional purchases within the local government budget, it depends on the financial ability of each local government. Therefore, there is a gap in the rabies prevention system of each local government. This means that there is a need to research determination of the quantity of bait vaccine to be scattered, followed by the density of raccoon dogs to prevent rabies successfully.

The bait vaccine is of a square brown solid shape 3-cm wide and 3-cm long. It confers immunity to wild animal after it is ingested together with the bait, such as fish cake or chicken meat dough. However, according to consultant interviews, some reported that the raccoon dog ate only the food parts (the surface of the bait vaccine) instead of the entire bait vaccine. The instructions were not issued clearly to the person scattering the bait vaccine, or scattering by the agents was inadequate, avoiding the optimal planned position. To monitor some projects, evaluation after scattering is required. There were many opportunities for untargeted animals to acquire the bait vaccine. Furthermore, the antibody-positive rate of target animal after scattering should be surveyed.

Direct inoculation of the rabies vaccine to abandoned animals (dogs and cats) is not easy. Inoculation in fierce dogs is also difficult. Oral vaccine methods for rabies prevention are more appropriate for such animals. Consequently, the less effective bait vaccine could be applied to dogs and cats.

In the companion animal (dog and cat) section, the government purchases rabies vaccine and syringes, and supplies these to local governments every spring and autumn. The local government distributes the vaccine and syringes to local veterinary clinics. Pet owners visit these clinics for rabies vaccination, and bear certain operation expenses. For dog vaccinations, education and public information are well established, and most companion dog owners have tried injecting their dogs with rabies vaccine. For cat vaccinations, however, despite the cat being an included animal inthe Prevention of Contagious Animal Diseases Act, insufficient public information has resulted in many cat owners not knowing that cats also require rabies vaccination. For vaccination timing, current policy involves a low-efficiency method with fixed terms (spring, autumn) and periods (2 weeks) every year. To prevent rabies, first inoculation is immediately provided in 3-month-old puppies. Subsequently, boosting inoculation is executed at an appropriate time under veterinarian control. However, there is the possibility of missing additional inoculation with current system of spring and autumn all-vaccination approach. Furthermore, owners attempt to vaccinate their pets during the campaign period to derive economic benefit, and it is possible that blank immunity elevation could occur, or the owner could give up on the vaccination due to the relatively short inoculation period. It means that the current policy could be relatively inefficient.

The operation expenses for clinics when rabies vaccine inoculations are executed require considerable adjustment to actual situations. When one animal comes to the hospital, outside of veterinarian labor cost, the expense of additional labor (if it is a large dog), disinfection, etc., should be expected. Inoculation side effects or being attacked are also outside of the responsibility and support of the government; the veterinarian is solely accountable. From July 1, 2011, value-added tax was added to the operation expense, reducing clinic expenses further. Then again, the distribution of rabies vaccine supply may also require adjustment. Without consideration of the size of the animal hospital or the number of clients, applying a uniform calculation for supply is an inefficient method.

In the farm animal (cow) section, rabies vaccine injections are performed after the vaccine is supplied to each farm directly. However, most farmers dislike cow rabies vaccinations. It is believed that one of the reasons for this is the possibility of live vaccine side effects. Farms in rabies-occurring regions are supplied inactivated vaccines, but farms in rabies non-outbreak regions are supplied live vaccines. In addition, farmers tend to neglect rabies vaccination, although they receive government compensation if a cow dies from vaccine side effects. It is also possible that the rate of rabies vaccination is low because the rabies vaccination certificate is not necessary for trade, unlike that for bovine brucellosis, and because the rabies vaccine is not essential for cows.

In the guard dog, hunting dog, and the others section, guard dogs that live in or around rabies outbreak regions to guard factories or farms are a rabies vaccination blind spot. Factory owners tend not to care about vaccinating these animals, and factory workers tend to be unconcerned about guard dog health. In hunting dogs, most large-scale breeders of hunting dogs focus on rabies vaccination, but small-scale breeders are not concerned about rabies vaccination for various reasons. Dogs initially bred for hunting that are retired and then released or abandoned into the wild become feral dogs that are more vulnerable to rabies and can infect humans. Applying regulations is difficult when it comes to abandoned dogs. An abandoned dog that has become feral is difficult to distinguish from a wild animal.

If an animal is not vaccinated, the owner can be charged and fined under the current prevention of contagious animal diseases Act Article 15 and Article 60. The enforcement decree of Article 16 of the Act states that first, second, and subsequent violations are liable for fines of $500, $2,000, and $5,000. However, cases in which offenders are actually fined by the government are rare.

Currently, there is no independent organization that bears exclusive responsibility for the rabies outbreak. In particular, rabies is not easy to be prevented by short-term plans. Therefore, an organization that executes rabies prevention plans continuously should be established.

The important transmitter animal is the wild raccoon dog, which spreads rabies to other animals. Research of the raccoon dog gene map has been performed using mitochondrial single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP). Based on nationwide analysis, this research has established that there are regional differences in raccoon dogs. However, additional research to create regional detailed gene maps is necessary. In addition, to analyze the gene map of the virus and target animals, it is necessary to request that central organizations such as the Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency analyze confirmed rabies samples in cooperation with other organizations.

When suspected animal rabies occurs, the government establishes a protection zone immediately within a 3-km radius and a surveillance zone within a 10-km radius of the outbreak site under consideration of geographic circumstances. After the protection and surveillance zones are established, the government orders a restriction on movement in important rabies-susceptible animals (dogs, cats, and cows). If the suspected animal is confirmed positive, the government orders the vaccination of all of major susceptible animals (dogs, cats, and cows aged >3 months). It also disinfects the farm on which the rabies occurred, and surrounding farms and facilities. If negative results based on clinical signs and laboratory analysis are confirmed, the barrier zone is cleared gradually. Clearance of the prevention zone is gradually processed from the surveillance zone to the protection zone. The protection zone is cleared 15 days after the protection zone and converted to a surveillance zone.

The movements of the suspected animal are restricted on to a secure facility to prevent contact with humans or other animals. The animal should be observed for clinical signs for at least 14 days; if it exhibits the typical clinical signs of rabies or is exposed to humans, it is slaughtered immediately and laboratory rabies diagnosis is requested. An epidemiologic survey is taken of the farm in which the suspected animal was located, spanning 1 month for cows and 6 months for dogs.

In a short-term strategy for rabies prevention, the prevention of spread from outbreak to non-outbreak regions is important. Intensive execution of the rabies prevention plan is necessary to prevent diffusion and additional outbreak in recent outbreak regions.

The bait vaccine prevention plan is a method that induces immunity against rabies in wild raccoon dogs to interrupt its role as a transmitter [2]. This method is effective as evaluated based on its cost and final effect. The scattering area and quantity of bait vaccine is estimated by considering the density of the wild raccoon dog population and recent rabies outbreak areas. Investigation by the Ministry of Environment determined that the prescribed density of the wild raccoon dog of 5 individuals per 100 ha was maintained continuously from 2002. Density in Jeonbuk was the highest, with 6.1 individuals per 100 ha; density in Gyeonggi-do was the lowest at 0.2 individuals per 100 ha. In areas in which scattering is difficult, such as mountains or swamps, scattering bait vaccine from airplanes or helicopters used for forest fire observation would be helpful, especially during the winter (Tables 8, 9).

It is possible that rabies antibody-negative wild raccoon dogs that infiltrate urban areas act as transmitters. Therefore, vaccination and antibody surveillance are necessary for livestock (cow) and pets (dog and cat) raised in farms close to the habitats of wild raccoon dogs. All rabies-susceptible animals within a rabies outbreak area should be vaccinated [2].

After vaccination, analysis of the antibody-positive rate in each Si and Gun should be performed. Si and Gun with <70% positive rates would require further measures. A survey of owners and animals should be performed to formulate vaccination and control plans. In particular, management control of hunting dogs during hunting season would be necessary.

There should be grounds to support more powerful legal restrictions to levy a fine for penalizing owners if animals within a rabies outbreak area and its vicinity are not vaccinated. If rabies occurs in a farm animal (cow), there should be grounds to support restrictions to examine rabies vaccination status; if a farm animal is unvaccinated, it should be excluded from slaughter compensation. If a patient was injured by biting, and suffered hydrophobia, there should be grounds to support legal restrictions that compel the owner of the animal that caused the injury to pay the total fee for treatment. This would prevent cases of vaccination evasion, which followed by administrative management enforcement, is expected to increase recognition of the importance of rabies prevention and vaccination by drawing attention to the responsibility of pet owners.

Abandoned animals (dog and cat) should be captured and slaughtered to control disease according to related provisions and to prevent secondary rabies infection. There should be additional procedures for performing serum analysis of rabies antibody status in the trapped animal, vaccination of the trapped animal with absence of rabies antibodies, and release of the vaccinated animal back to nature as in current trap-neuter-release (TNR) programs [12].

A short-term prevention strategy is insufficient for exterminating rabies; a long-term prevention strategy should be implemented to control rabies. The OIE determines a rabies-free state based on no rabies outbreak in humans and animals over 2 years. It is necessary to aim for a rabies-free base condition and to maintain the control system over 2 years to acquire the status of a rabies-free state by 2018. The 10 southeast Asian countries have announced a rabies free-state declaration and aim to be declared rabies-free states by 2020.

It is necessary to create a rabies responsibility department in each local government. To exterminate rabies, a specialty organization responsible for the control and management of rabies with professional manpower and a specialty facility is needed. This exclusive-responsibility organization will perform various programs and policies on rabies vaccination, evaluation, surveillance, and post-monitoring.

There should be PR of target animals such as the wild raccoon dog in Korea by slaughtering or other methods. In addition to the current bait vaccine and injectable vaccine programs, systematic introduction of PR, TVR, and OVR complex programs to control rabies would be helpful. PR would apply to a 1-km radius from rabies outbreak areas, considering the 3.4-km2 wild raccoon dog territory. It is difficult to obtain permission to use firearms at night in Korea, thus an easier approach of using hunting dog to reduce wild raccoon dog populations should be considered [20].

TVR programs are a method of maintaining therate of rabies antibody in wild raccoon dogs that repeat the cycle of capturing (trap), vaccinating, and individually tagging wild raccoon dogs according to a schedule of a rabies immunity level. The objective of this program is to minimize rabies diffusion from high-risk regions to natural regions. The TVR program applies to a 1-5-km radius from a rabies outbreak spot considering the 3.4-km2 wild raccoon dog territory. For application of this program, it is necessary to follow the below steps. First, the TVR program is added to the national quarantine program in the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs by political proposal. There is a need to select a proper application area for TVR programs around rabies outbreak spots. The density of wild raccoon dogs inthe application area devided by 1 km2 should be confirmed. There should be 50-75 capture traps per 1-km2 sector and where the wild raccoon dog mainly passes. The captured raccoon dog is vaccinated; if needed, confirmation of the vaccine tag for records or RFID chips after neutralization operation is done. Next, the captured raccoon dog is released to the same location. This is repeated until 70% rabies antibody distribution is maintained and the informationis input to the Korea Animal Health Integrated System.

OVR is a rabies preventive measure using the bait vaccine [21]. The bait vaccine strategy is recognized as the most effective preventive measure. Preventive measures using the bait vaccine has made continuous progress in Korea. As a result, there was no report of rabies infection in Gyeonggi-do from 2006 to 2011 and rabies infection in Gangwon-do has tended to decrease. This program is applied within a 5-km radius from a rabies outbreak spot [14].

When raccoon dogs are hungry, they easily accept bait vaccines. Bait vaccines are principally distributed when there is insufficient food in their habitat, before bait is covered in snow and fallen leaves, and when raccoon dogs are active. During November and December, according to locality, there is not enough food. During this time, raccoon dogs have a huge appetite to build up body fat for the hibernation period but find it difficult to find sufficient food. Moreover, during mid-February and mid-March, raccoon dogs wake up from hibernation and actively look for food to compensate for the energy shortage during the winter and start mating. It is recommended that bait vaccines be distributed first in spring (around March) and then in autumn (around November).

There are 2 ways to distribute bait vaccines: direct and through air. Direct distribution involves scattering the bait vaccine by hand and regularly checking ingestion. Distributors should wear 2-layer gloves (inner cotton gloves, outer rubber gloves) to mask the human scent. This distribution method is what the Korean government has used.

Air distribution involves dropping bait vaccine from the air by airplane or helicopter in regular cycles and density. This method can cover a large area such as the province of Ontario, Canada, and the states of New York, USA [12]. It can be applied to the demilitarized zone (DMZ) and woodlands where access to humans is difficult. In civilian access-restricted regions in particular, it is recommended that bait vaccines be distributed by air. During air distribution, distributors should take care not to injure people or damage houses, pens, or greenhouses with the falling bait vaccine. In army bases near the DMZ, personnel often encounter raccoon dogs searching for food.

Post-management of bait vaccine distribution performed as follows. Bait vaccine intake rate is analyzed by re-visiting the distribution area after a certain period from the distribution date. However, this method is limited in that there is no assurance that the target animal has taken the bait vaccine. To ensure that the target animal takes the bait vaccine, CCTV use is necessary. In bait vaccine-distributed areas (Gyeonggi-do, Gangwon-do), analyses of rabies antibody from raccoon dogs are required. The goal is maintain an average antibody-positive rate of 70%. The method involves re-visiting the distribution area to check intake of the bait vaccine and collect the remaining bait vaccine. After 4 weeks from re-visiting day, wild animals, especially raccoon dogs, are captured for sampling in the distribution area. The captured animals are tagged. Blood samples are collected from the animals and they are released where they were caught. Rabies antibody titers are tested using the collected blood. However, the effectiveness of the bait vaccine related with application dose and period is not researched. Therefore, surveys are recommended to determine the optimal application dose of bait vaccine.

The most important data of the rabies preventive strategy is defining vaccinated animals and investigating the habitats of animals and livestock. Each local government has to determine how many animals are in their area. For this purpose, local governments compulsorily count all animals (companion animals, livestock) and enter the findings in a computerized database. In the companion animal part, making a connection with the Companion Animal Registration System is useful to counting. Therefore, local governments actively encourage animal owners to register. In addition, local governments need to manage and count abandoned animals. Such animals usually do not have rabies vaccination and do not have stable habitats, thus they are prone to contact with wild raccoon dogs. Subsequently, they are easily infected with rabies and may even encounter and bite humans. To reduce this route of infection, an Animal Registration Policy could help to reduce the number of abandoned animals and increase their chances of finding their owner.

As this research has shown, current vaccine strategies have some weaknesses relating to both companion animals and livestock. Some solutions are recommended to solve these problems. The government needs to modify the current rabies vaccine policy. Currently, rabies vaccine through veterinary hospitals twice a year within a limited period is mandatory. Instead of that, a more effective way to control rabies vaccination in companion animals is for owners to bring their companion animals to veterinary hospitals at their convenience and pay for the rabies vaccine. The government only advertises the importance of the rabies vaccine and encourages owners to bring their companion animals to veterinary hospitals. Veterinary hospitals are in charge of the rest of the process, such as injecting the rabies vaccine, handing the side effects, and notifying owners of the vaccine due date. There is an argument about increasing the cost to owners. This can be solved by explaining and promoting the reasons and necessity of the rabies vaccine to owners. In addition, connecting with the Animal Registration System means that rabies vaccination records can be managed effectively and owners who do not adhere to the policy can be fined, improving the rabies vaccination rate in companion animals.

According to previous data, the rabies antibody titer of dogs during the last 5 years was 64.7% and that of cattle was 46.1%. This result means that cattle receive less rabies vaccination than dogs. Internationally, an average 70% rabies antibody-positive rate is required for adequate management of rabies infection. The 70% rabies antibody-positive rate should be maintained with regular vaccinations and tests. The best time to collect blood samples for rabies antibody testing is 1-2 months after rabies vaccination.

Registering animals (if not, the owner should be fined) can decrease the number of abandoned animals. To prevent secondary rabies infection in abandoned animals (dogs and cats), they should be captured and euthanized according to the related regulations to regulate their population. In TNR programs, rabies antibody titer testing should be done and rabies vaccination administered depending on antibody level. Capture and vaccination cannot cover all abandoned animals. Bait vaccine for dogs and cats should be developed and distributed.

Guard dogs are exposed to rabies infection because they easily come into contact with raccoon dogs. Their population should be analyzed and owners advised to administer the rabies vaccine. If not, the owner should be fined, followed by relative regulation.

It is difficult to define feral abandoned animals that settle in mountains near urban areas as wild animals or abandoned animals. It is uncertain which government regulations and decisions to apply. Consequently, laws and regulations should be modified to clarify this.

The most important rabies carrier in South Korea is the wild raccoon dog. Genome mapping of raccoon dogs can elucidate how rabies is spread. Currently, there are 2.5 million dog SNPs. Using these, the raccoon dog genome could be mapped effectively with SNPs or short tandem repeats. For genome mapping, genome analysis of raccoon dogs with confirmed diagnosis of rabies should be requested to government laboratories (Animals and Plants Quarantine Agency).

Residents and visitors to rabies-prevalent areas should be educated about the raccoon dog and that wild animal bites can induce rabies infection. In addition, when suspicious animals are found, people should report them to local government and Veterinary Service Laboratory and not attempt capture without safety equipment. They should be educated about how to deal with bite wounds from wild animals. Livestock farmers need to learn the necessity of rabies vaccination to their domestic animals. Moreover, this education should be provided nationwide and regularly to educate the nation about rabies infection. Personnel at military bases in rabies-prevalent areas should be taught rabies prevention. Residents and visitors to rabies-prevalent areas should be educated on the purpose of the bait vaccine. Bait vaccine distributors should follow the manufacturer's instruction. Some distributors do not distribute the bait vaccine at the designated sites. In particular, people in charge of prevention need to have specialized education and training about the bait vaccine. At national parks and trail entrances, public information on rabies should be displayed.

A consultative group should be formed with the various relevant authorities to control rabies. The Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency administers the rabies antibody titer test, develops the bait vaccine, and maps the raccoon dog genome. The Ministry of Environment and National Institute of Environmental Research should build the database of wild animals and measure raccoon dog regional density. The Ministry of Health and Welfare and the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention should manage rabies special management area and co-research. The Ministry of National Defense should draft an initial response manual for rabies outbreak in the DMZ, assign the DMZ as a rabies buffer zone, distribute the bait vaccine in the DMZ, and educate personnel about rabies infection. The Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transportation and the Ministry of Environment should conduct prior environmental review before city development and prepare substitute habitats to prevent wild animals moving into urban areas. The Korea Forest Service should research wild animal habitats in forest areas and cooperate in distribution of the bait vaccine. The Korea Expressway Corporation should notify drivers about wild animals. It should also research which wild animals are prone to encounter pavements and cars. Gyeonggi-do (Livestock and Veterinary Service), Gangwon-do (Veterinary Service Laboratory) should construct a cooperation network with the First Crops.

As most rabies outbreaks occur around the DMZ, there are rabies infections in North Korea. Therefore, joint research between South and North Korea would promote epidemic rabies preventative activity. To accomplish this, international institutes such as the World Health Organization (WHO), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and OIE strongly recommend research to North Korea.

The outbreak of rabies infection, that occurred at Suwon and Hwaseong, which are densely populated areas, must be seriously considered, as there is a chance that people can be infected with rabies. The present rabies control strategy is a short-term prevention that was designed on a limited budget. It is economically efficient but does not effectively eradicate rabies outbreaks. Followed by public officers in charge of rabies control strategy, the present budget and manpower are insufficient to eliminate rabies infection. To solve rabies problems, the budget and manpower for rabies control strategy should be increased and combined with a reconstructed long-term rabies control strategy. This report is based on on-site inspections that uncovered the present weaknesses of the rabies control strategy.

Figures and Tables

Table 2

Rabies outbreak in Korea by area (1997-2012)

Data source: Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency [9].

Values are presented as number of animals. The numbers in parentheses represent the number of including racoon dog.

Table 3

Rabies outbreak in Korea by species

Data source: Animal, Plant and Fisheries Quarantine and Inspection Agency [7].

Table 4

Hydrophobia outbreak in Korea

Data source: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [8].

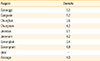

Table 6

Seroprevalence of rabies in Korea by year

Data source: Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency [9].

Table 7

Regional seroprevalence of rabies in Korea

Data source: Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency [9].

References

1. Hymann DL. Control of communicable disease manual. 18th ed. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association;2004.

2. Hankins DG, Rosekrans JA. Overview, prevention, and treatment of rabies. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004; 79:671–676.

3. de Mattos CA, de Mattos CC, Smith JS, et al. Genetic characterization of rabies field isolates from Venezuela. J Clin Microbiol. 1996; 34:1553–1558.

4. Hyun BH, Lee KK, Kim IJ, et al. Molecular epidemiology of rabies virus isolates from South Korea. Virus Res. 2005; 114:113–125.

5. Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency. National report. Anyang: Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency;2011.

6. Kim CH, Lee CG, Yoon HC, et al. Rabies, an emerging disease in Korea. J Vet Med B Infect Dis Vet Public Health. 2006; 53:111–115.

7. Animal, Plant and Fisheries Quarantine and Inspection Agency. National report. Anyang: Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency;2009.

8. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public strategy developement for civils and medicals. Seoul: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2007.

9. Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency. Epidemiology report of Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency. Anyang: Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency;2012.

10. Lee JH, Lee MJ, Lee JB, Kim JS, Bae CS, Lee WC. Review of canine rabies prevalence under two different vaccination programmes in Korea. Vet Rec. 2001; 148:511–512.

11. Hirsch BT, Prange S, Hauver SA, Gehrt SD. Raccoon social networks and the potential for disease transmission. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e75830.

12. Rosatte R, Donovan D, Allan M, et al. Rabies in vaccinated raccoons from Ontario, Canada. J Wildl Dis. 2007; 43:300–301.

13. Ballesteros C, Gortazar C, Canales M, et al. Evaluation of baits for oral vaccination of European wild boar piglets. Res Vet Sci. 2009; 86:388–393.

14. Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency. Rabies eradication plan using bait vaccine in Korea. Anyang: Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency;2001.

15. Middaugh J, Ritter D. A comprehensive rabies control program in Alaska. Am J Public Health. 1982; 72:384–386.

16. Ohio Department of Health. Zoonotic disease program: oral rabies vaccination [Internet]. Columbus: Ohio Department of Health;2013. cited 2013 Apr 19. Available from: http://www.odh.ohio.gov/odhprograms/dis/zoonoses/rabies/orv/orv1.aspx.

17. Rosatte RC, Power MJ, MacInnes CD, Campbell JB. Trap-vaccinate-release and oral vaccination for rabies control in urban skunks, raccoons and foxes. J Wildl Dis. 1992; 28:562–571.

18. Neubert A, Schuster P, Muller T, Vos A, Pommerening E. Immunogenicity and efficacy of the oral rabies vaccine SAD B19 in foxes. J Vet Med B Infect Dis Vet Public Health. 2001; 48:179–183.

19. World Animal Health Information Database (WAHID) interface [Internet]. Paris: World Organisation for Animal Health;2012. cited 2013 Apr 19. Available from: http://www.oie.int/wahis_2/public/wahid.php/Wahidhome/Home.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download