Abstract

Purpose

The aims of this study were to examine indoor concentrations of air pollutants in socioeconomically disadvantaged houses and to investigate relationships between indoor air pollutant levels and the severity of atopic dermatitis (AD).

Methods

A total of 54 children who had a past history or current symptoms of AD were enrolled in the study. To evaluate the levels of indoor air pollutants, we measured concentrations of CO2, total volatile organic compounds (TVOC), formaldehyde, particulate matter with diameter less than 10 µm (PM10), airborne mold and numbers of house dust mite (HDM) in dust of the children's houses. All studied subjects completed physical examination for the severity of AD and blood tests.

Results

Although the mean (±standard deviation [SD]) concentration of indoor CO2 (600.6±179.4 ppm) was lower than the standard recommended levels of multiplex buildings in Korea, there was a significant correlation between CO2 concentrations and the severity of AD (r=0.302, P=0.030). The geometric means (range of 1 SD) of TVOC (42.5 µg/m3 [22.2-81.5]), formaldehyde (24.3 µg/m3 [15.0-39.9]), PM10 (26.6 µg/m3 [14.6-48.4]), and airborne mold (49.9 CFU [colony forming unit]/m3 [26.3-94.6]) were not significantly higher than the standard recommended levels of multiplex buildings. Two-thirds of the subjects were sensitized to at least 1 of the common allergens.

Conclusion

Generally, indoor air pollution was not serious in socioeconomically disadvantaged households. However, indoor CO2 concentrations are closely related to the severity of AD in children living in socioeconomically disadvantaged houses. Environmental amelioration targeting vulnerable population may improve the quality of life and decrease the prevalence of environmental allergic diseases.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Correlations between indoor CO2 concentrations and SCORAD index in socioeconomically disadvantaged children. SCORAD, SCORing Atopic Dermatitis.

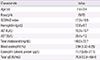

Table 1

General characteristics of subjects in this study

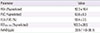

Table 2

Pulmonary function parameters and FeNO levels of the studied subjects

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| FEV1 (%predicted) | 92.3 ± 10.4 |

| FVC (%predicted) | 93.6 ± 9.3 |

| FEV1/FVC (%) | 90.4 ± 3.5 |

| FEF25%-75% (%predicted) | 103.3 ± 20.5 |

| FeNO (ppb) | 20.5 (11.0-38.1) |

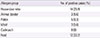

Table 3

Prevalence of sensitization to the allergen groups in the studied subjects

| Allergen group | No. of positive cases (%) |

|---|---|

| House dust mite | 14 (25.9) |

| Animal dander | 3 (5.6) |

| Pollen | 5 (9.3) |

| Mold | 3 (5.6) |

| Cockroach | 0 (0) |

| Food | 12 (22.2) |

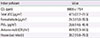

Table 4

Concentrations of indoor pollutants in dwellings of the studied subjects

Table 5

Associations between SCORAD index and, health outcomes and indoor pollutants levels in dwellings of the studied subjects

References

1. Baek JO, Hong S, Son DK, Lee JR, Roh JY, Kwon HJ. Analysis of the prevalence of and risk factors for atopic dermatitis using an ISAAC questionnaire in 8,750 Korean children. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2013; 162:79–85.

2. Bakke JV, Wieslander G, Norback D, Moen BE. Eczema increases susceptibility to PM10 in office indoor environments. Arch Environ Occup Health. 2012; 67:15–21.

3. Ahn K. The role of air pollutants in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014; 134:993–999.

4. Seo S, Kim D, Paul C, Yoo Y, Choung JT. Exploring household-level risk factors for self-reported prevalence of allergic diseases among low-income households in Seoul, Korea. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2014; 6:421–427.

5. Wen HJ, Chen PC, Chiang TL, Lin SJ, Chuang YL, Guo YL. Predicting risk for early infantile atopic dermatitis by hereditary and environmental factors. Br J Dermatol. 2009; 161:1166–1172.

6. Matsunaga I, Miyake Y, Yoshida T, Miyamoto S, Ohya Y, Sasaki S, et al. Ambient formaldehyde levels and allergic disorders among Japanese pregnant women: baseline data from the Osaka maternal and child health study. Ann Epidemiol. 2008; 18:78–84.

7. Ou CQ, Hedley AJ, Chung RY, Thach TQ, Chau YK, Chan KP, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in air pollution-associated mortality. Environ Res. 2008; 107:237–244.

8. O'Neill MS, Jerrett M, Kawachi I, Levy JI, Cohen AJ, Gouveia N, et al. Health, wealth, and air pollution: advancing theory and methods. Environ Health Perspect. 2003; 111:1861–1870.

9. Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol (Stockh). 1980; 2:44–47.

10. Severity scoring of atopic dermatitis: the SCORAD index. Consensus Report of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatology. 1993; 186:23–31.

11. Beydon N, Davis SD, Lombardi E, Allen JL, Arets HG, Aurora P, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: pulmonary function testing in preschool children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007; 175:1304–1345.

12. Dweik RA, Boggs PB, Erzurum SC, Irvin CG, Leigh MW, Lundberg JO, et al. An official ATS clinical practice guideline: interpretation of exhaled nitric oxide levels (FENO) for clinical applications. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011; 184:602–615.

13. Seo SC, Dong SH, Kang IS, Yeun KN, Choung JT, Yoo Y, et al. The clinical effects of forest camp on children with atopic dermatitis. J Korean Ins For Recreation. 2012; 6:21–31.

14. Kang MS. A survey of biological contaminations in a residential environment of the selected disadvantaged households [dissertation]. Seoul: Korea University;2011.

15. Dei-Cas I, Dei-Cas P, Acuna K. Atopic dermatitis and risk factors in poor children from Great Buenos Aires, Argentina. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009; 34:299–303.

16. Kim HO, Kim JH, Cho SI, Chung BY, Ahn IS, Lee CH, et al. Improvement of atopic dermatitis severity after reducing indoor air pollutants. Ann Dermatol. 2013; 25:292–297.

17. Dust mite allergens and asthma: a worldwide problem. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1989; 83(2 Pt 1):416–427.

18. World Health Organization. Environment and health risks: a review of the influence and effects of social inequalities. Geneva: World Health Organization;2010.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download