Abstract

Purpose

We investigated the causes, clinical features, and risk factors of bee venom anaphylaxis in Korea.

Methods

The medical records of the diagnosis of anaphylaxis during a 5-year period from the 14 hospitals in Korea have been retrospectively reviewed. Cases of bee venom anaphylaxis were identified among anaphylaxis patients, and subgroup analyses were done.

Results

A total of 291 patients were included. The common cause of bee species was vespid (24.6%) in bee venom anaphylaxis, followed by honeybee and vespid (8.8%), apitherapy (7.7%), and honeybee (2.0%), although the causative bee species were commonly unknown (56.9%). The severity of anaphylaxis was mostly mild-moderate (72.9%), and common clinical manifestations included cutaneous (80.6%), cardiovascular (39.2%), respiratory (38.1%), and gastrointestinal (13.1%) symptoms. Portable epinephrine auto-injectors were prescribed to 12.1% of the patients. Subject positive to both vespid and honeybee showed more severe symptoms and higher epinephrine use (P<0.05). The severity was significantly associated with older age, but not with gender, underlying allergic disease, or family history. Apitherapy-induced anaphylaxis showed a higher rate of hospitalization and epinephrine use than bee sting anaphylaxis (P<0.05).

Figures and Tables

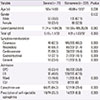

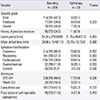

Table 3

Comparison of clinical parameters between the causes in bee venom anaphylaxis

Values are presented as number of subjects (%) unless otherwise indicated. Denominators are number of patients from which data collection was available.

SD, standard deviation; OPD, outpatient department; ER, emergency room; ICU, intensive care unit.

*P-value is compared among Honeybee, Vespid, and Honeybee+vespid groups.

References

2. Cianferoni A, Novembre E, Mugnaini L, Lombardi E, Bernardini R, Pucci N, et al. Clinical features of acute anaphylaxis in patients admitted to a university hospital: an 11-year retrospective review (1985-1996). Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2001; 87:27–32.

3. Ye YM, Kim MK, Kang HR, Kim TB, Sohn SW, Koh YI, et al. Anaphylaxis in Korean adults: a multicenter retrospective case study. Korean J Asthma Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012; 32:S226.

4. Clark S, Camargo CA Jr. Epidemiology of anaphylaxis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2007; 27:145–163.

5. Lockey RF, Bukantz SC. Allergen immunotherapy. . New York: Marcel Dekker;1991.

6. Bilo BM, Rueff F, Mosbech H, Bonifazi F, Oude-Elberink JN. EAACI Interest Group on Insect Venom Hypersensitivity. Diagnosis of Hymenoptera venom allergy. Allergy. 2005; 60:1339–1349.

7. Golden DB, Marsh DG, Freidhoff LR, Kwiterovich KA, Addison B, Kagey-Sobotka A, et al. Natural history of Hymenoptera venom sensitivity in adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997; 100(6 Pt 1):760–766.

8. Neugut AI, Ghatak AT, Miller RL. Anaphylaxis in the United States: an investigation into its epidemiology. Arch Intern Med. 2001; 161:15–21.

9. Kim SS, Park HS, Kim HY, Lee SK, Nahm DH. Anaphylaxis caused by the new ant, Pachycondyla chinensis: demonstration of specific IgE and IgE-binding components. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001; 107:1095–1099.

11. Kang S, Chang S, Min K, Moon H, Choi B, Kee M. A survey on the bee venom allergy in children of a rural area. Allergy. 1987; 7:1–7.

12. Kim YK, Jang YS, Jung JW, Lee BJ, Kim HY, Son JW, et al. Prevalence of bee venom allergy in children and adults living in rural area of Cheju Island. J Asthma Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998; 18:451–457.

13. Im JH, Kwon HY, Ye YM, Park HS, Kim TB, Choi GS, et al. Food-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis in Korea: a multicenter retrospective case study. Allergy Asthma Respir Dis. 2013; 1:203–210.

14. Brown SG. Clinical features and severity grading of anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004; 114:371–376.

15. Lee JD, Park HJ, Chae Y, Lim S. An overview of bee venom acupuncture in the treatment of arthritis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2005; 2:79–84.

16. Mueller UR. Cardiovascular disease and anaphylaxis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007; 7:337–341.

17. Rueff F, Placzek M, Przybilla B. Mastocytosis and Hymenoptera venom allergy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006; 6:284–288.

18. Bilo BM, Bonifazi F. Advances in hymenoptera venom immunotherapy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007; 7:567–573.

19. Kim JC, Kim SC, Kim YS, Kim CH, Do HH, Lee BS, et al. Clinical study of anaphylactic patients with bee stings who visited the Emergency Department. J Korean Soc Emerg Med. 2005; 16:403–409.

20. Bilo BM, Bonifazi F. Epidemiology of insect-venom anaphylaxis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008; 8:330–337.

21. Fernandez J, Blanca M, Soriano V, Sanchez J, Juarez C. Epidemiological study of the prevalence of allergic reactions to Hymenoptera in a rural population in the Mediterranean area. Clin Exp Allergy. 1999; 29:1069–1074.

22. Sturm GJ, Heinemann A, Schuster C, Wiednig M, Groselj-Strele A, Sturm EM, et al. Influence of total IgE levels on the severity of sting reactions in Hymenoptera venom allergy. Allergy. 2007; 62:884–889.

23. Ali MA. Studies on bee venom and its medical uses. Int J Adv Res Technol. 2012; 1:69–83.

24. Jung JW, Jeon EJ, Kim JW, Choi JC, Shin JW, Kim JY, et al. A fatal case of intravascular coagulation after bee sting acupuncture. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2012; 4:107–109.

25. Clark S, Long AA, Gaeta TJ, Camargo CA Jr. Multicenter study of emergency department visits for insect sting allergies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005; 116:643–649.

26. Park JW, Nahm DH, Hong CS. Detection of honeybee venom specific igE and igG4 in honeybee venom allergy. Allergy. 1993; 13:312–325.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download