Case Report

A 63-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with recurrent aspiration pneumonia, dysphagia and neck pain in June 2014. The patient was paraplegic due to a C6 to C7 fracture and dislocation and had been operated on 8 years previously. At that time of trauma, initial surgical treatment was ACDF C6 to C7 and posterior wire fixation (

Figure 1). He had a chronic ill appearance due to daily spiking fever. Simple chest X-ray showed haziness on right lower lobe suggestive of aspiration pneumonia. Lateral cervical radiograph indicated a good fusion, normally positioned cervical plate, screw and interspinous wiring. Serologic tests showed increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein. The patient also complained of dysphagia and neck pain and cervical esophagoscopy was accordingly performed. Esophagoscopy indicated the site of perforation with exposed metal plate in the esophageal lumen at the approximate level ofthe cricoid cartilage and extending slightly below (

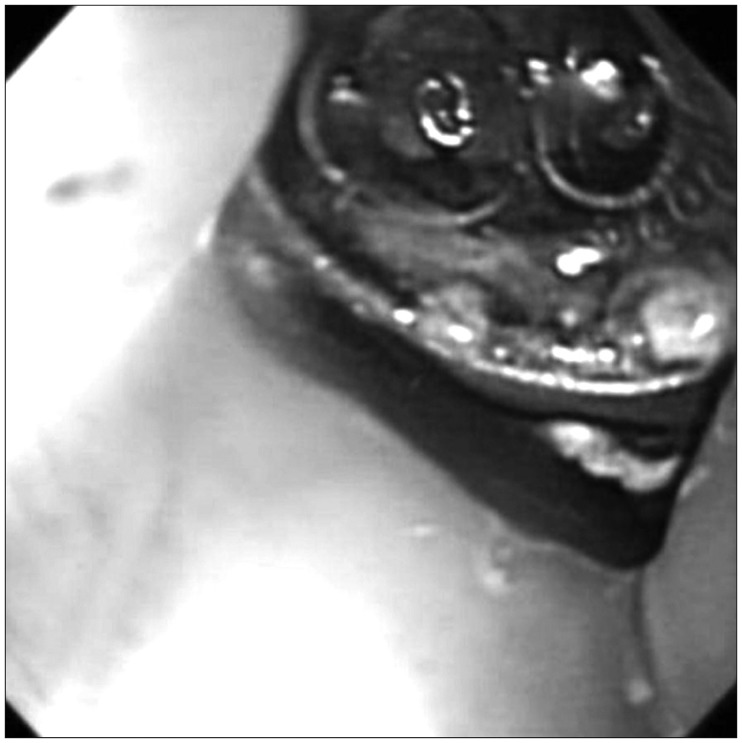

Figure 2). Computed tomography (CT) at the cervical level revealed communication of the esophagus and the plate (

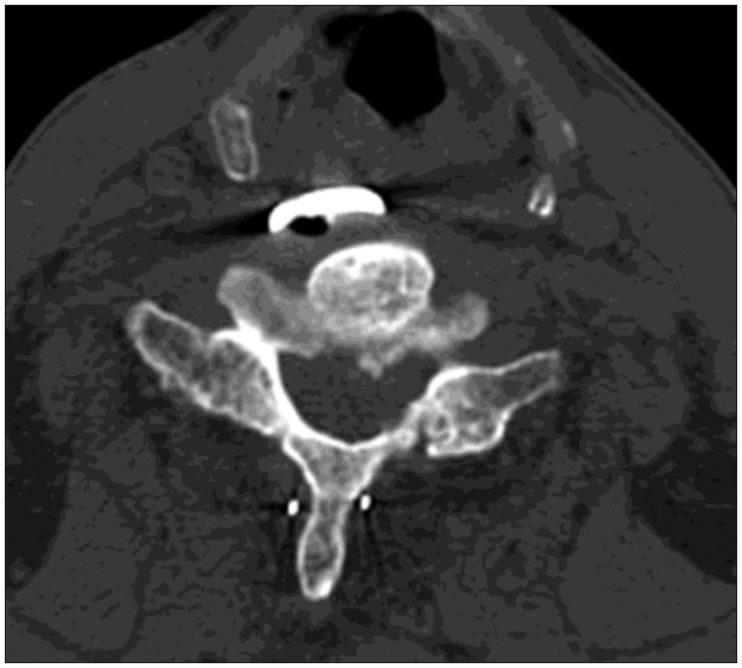

Figure 3). Patient was subsequently scheduled for surgery. Before surgery, patient underwent preoperative vocal cord inspection, in order to plan approaches based on this result. Since vocal cord inspection was normal, the surgical approach was in the opposite direction as the previous cervical surgery to avoid revision-related complications. A thoracic surgeon joined the operation team to repair the defect of the esophagus. Dissection between the plate and esophagus was difficult because of severe fibrosis. After debridement of fibrosis between the posterior wall of esophagus and plate, the medial and lateral surface of the right sternocleidomastoid muscle was exposed and a superior-based pedicled flap was prepared. The closure was reinforced with a sternocleidomastoid muscle flap by the thoracic surgeon.

| FIGURE 1Lateral radiograph of the cervical spine showing appropriate placement of the plate from C6 to C7 without hardware failure.

|

| FIGURE 2Esophagoscopic image shows the cervical plate protruding through the posterior wall of the esophagus.

|

| FIGURE 3Preoperative cervical spine computed tomographic scan shows the prevertebral gas between plate and spinal column.

|

After surgery, intravenous antibiotics were administered, while placing nasogastric feeding tube for 3 weeks. Further progress was favorable with no evidence of local infection. A contrast-medium swallowing study was performed at 3 weeks postoperatively. There was no esophageal extravasation, but silent aspiration of the contrast medium was observed. Therefore, nasogastric feeding tube was maintained until the patient was discharged and transferred to the local rehabilitation center.

Go to :

Discussion

The complications of ACDF are well known and include bone graft failure, tracheoesophageal injury, carotid artery injury, cerebrospinal fluids leakage, recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, roots and cord injury. The complication rate of this procedure is about 5% and decreases with surgeon's experience.

9) Newhouse et al.

8) in a survey of the Cervical Spine Research Society reported 22 cases of esophageal injury after ACDF. In this study, 6 cases occurred at the time of surgery, 6 in the postoperative periods and 10 in weeks to months later. Gaudinez et al.

6) identified 44 (1.49%) patients of esophageal injury related to the cervical operation in a series of 2,946 patients with cervical fractures. Twenty-eight patients (77%) of the 44 cases occurred intraoperatively. As in our case, delayed esophageal perforation after 8 years post-ACDF is rare. One of the unique features of our case is the long (>8 years) asymptomatic period between ACDF and development of a delayed esophageal perforation. With the exception of recurrent aspiration pneumonia and dysphagia after cervical surgery, our patient was asymptomatic until 8 years after the ACDF. Unlike many other reported cases presenting with delayed esophageal perforation after ACDF, there were no signs of hardware failure, or graft displacement.

Since complication related esophagus injury varies from local infection to septic condition, esophageal perforation could be the one of the most serious complication. Esophageal secretions that contain micro-organisms infect the surrounding structure. Therefore, esophageal perforation can lead tosimple local infection, subsequent osteomyelitis, mediastinitis, pleuritis, pericarditis, systemic sepsis and death.

711) The mortality of these conditions with conservative therapy is reportedly as high as 65%.

12)

Most common causes of acute esophageal perforation are an injury from surgical instrumentation and the pressure of the esophagus between sharp retractor and nasogastric tube. Meanwhile, the causes of delayed injury are chronic irritation and compression between esophagus and hardware/graft. The risk of which can be reduced through cervical plating system.

7) However, another cause of delayed injury is the chronic friction between posterior wall of esophagus and plating system normally positioned with adhesion and traction-type pseudodiverticulum.

1314) In our case, there was no radiographic evidence of cervical instrumentation failure. However, the cause of delayed esophageal perforation is unclear and could possibly include chronic friction and pressure between cervical plate and posterior wall of the esophagus.

A diagnosis of esophageal injury is made by symptoms and imaging techniques. If the perforation is recognized intraoperatively, simple primary suture repair may be adequate. However, if the patient complains of fever, dysphagia, neck swelling, local subcutaneous emphysema and any sign of infection immediately after ACDF, the surgeon should consider esophageal injury.

4512) Compared to the acute esophageal injury, symptoms of delayed esophageal perforations are mostly dysphagia and sign of infection, as in our case. These symptoms lead to a high level of suspicion to diagnose delayed esophageal perforation.

6) Numerous imaging techniques are useful in the diagnosis of esophageal injury. Plain neck X-ray may show such indirect signs such as subcutaneous emphysema, migration of the screw/graft, dislodgment of the plate, prevertebral air and soft tissue edema. Contrast esophageal study and esophagoscopy can identify fistula, graft displacement, abscess formation and hardware failure. Neck CT scan could detect the presence of an abscess and graft displacement with a sensitivity of 80%.

1013) Sometimes, surgery is required for 18% of the patients in order to confirm the diagnosis.

67) The patient in our case had experienced recurrent aspiration pneumonia and complained of neck pain and dysphagia. Therefore, esophagoscopy and cervical CT scan were performed. Cervical esophagoscopy evidenced an exposed metal plate in esophageal lumen and the prevertebral gas was observed between plate and vertebral body in CT scan.

Basic treatment of delayed esophageal perforation is to drain the abscess, remove the hardware and repair the perforation site. Non-surgical treatment (including antibiotic therapy) is indicated when defect size is small (<1 cm) with asymptomatic patients.

7) Surgical treatment is the gold standard if the diameter of the defect is >1 cm or any sign of local infection are observed.

7) In these cases, primary closure may be performed with or without muscle flap interposition.

101314)

In our case, direct esophagoscopy revealed an exposed cervical plate was embedded in the esophageal lumen. Additionally, patient complained of dysphagia and sign of infection. As a result of these findings, patient was scheduled for surgery with sternocleidomastoid muscle flap to control the infection and closure the larger defect.

Go to :