Abstract

Objective

The importance of traumatic dural venous sinus injury lies in the probability of massive blood loss at the time of trauma or emergency operation resulting in a high mortality rate during the perioperative period. We considered the appropriate methods of treatment that are most essential in the overall management of traumatic dural venous sinus injuries.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective review of all cases involving patients with dural venous sinus injury who presented to our hospital between January 1999 and December 2014.

Results

Between January 1999 and December 2014, 20 patients with a dural venous sinus injury out of the 1,200 patients with severe head injuries who had been operated upon in our clinic were reviewed retrospectively. There were 17 male and 3 female patients. In 11 out of the 13 patients with a linear skull fracture crossing the dural venous sinus, massive blood loss from the injured sinus wall could be controlled by simple digital pressure using Gelfoam. All 5 patients with a linear skull fracture parallel to the sinus over the venous sinus developed massive sinus bleeding that could not be controlled by simple digital pressure.

Go to :

Among all craniocerebral injuries, the incidence of dural venous sinus injury caused by head trauma ranges from 1 to 4 percent in civilian life in the respective literature.3410) The importance of such an injury lies in the probability of massive blood loss at the time of trauma or emergency operation resulting in a high mortality rate during the perioperative period. Despite its importance, this kind of injury diagnosed preoperatively in only about half of the respective cases and it places high demands upon the treating neurosurgeon.6) Therefore, we performed a review of the clinical features, management, and outcome of patients who were treated at our hospital with traumatic dural venous sinus injury.

Go to :

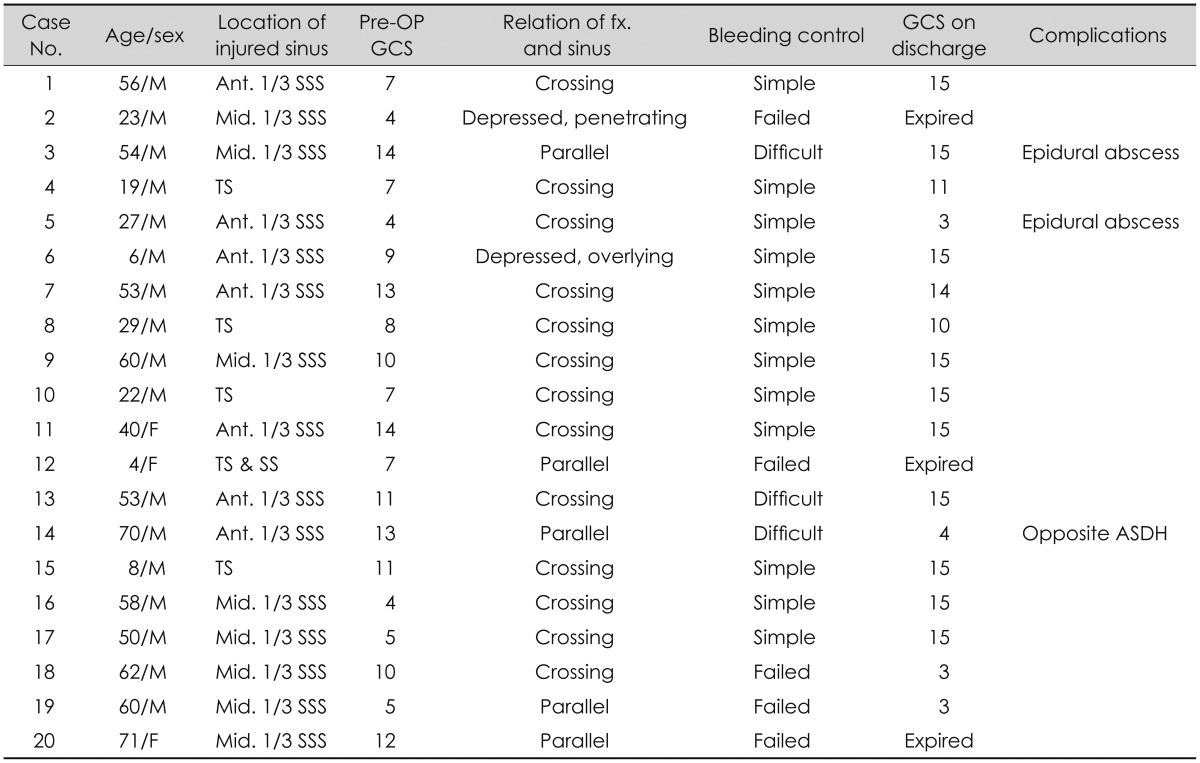

A retrospective review was conducted for all patients between January 1999 and December 2014 with dural venous sinus injury. We included only surgically treated cases among them. For each patient, demographic data, including age, sex, intraoperative control of bleeding, and postoperative complications, were recorded (Table 1). Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score was used to determine the neurological status.

On admission, skull X-rays and computed tomography (CT) scans were taken in all cases. The shape of the skull fracture and location of the injured sinus were recorded. The skull fracture pattern seen on the initial skull X-ray and CT was classified by relation of the injured sinus (crossing, parallel, depressed and overlying, and depressed and penetrating). Angiographic examination was not performed in any of the cases due to the emergency situation.

From the operation reports, the amount of blood loss, control of hemorrhage, and the amount of transfused blood were noted. The term of 'simple' bleeding control was defined when the sinus bleeding could be stopped by simple digital pressure using Gelfoam. The 'difficult' bleeding control was defined when the sinus bleeding could not be stopped by simple digital pressure.

Go to :

From January 1999 to December 2014, twenty patients with a dural venous sinus injury out of the 1,200 patients with severe head injuries who had been operated in our clinic were reviewed retrospectively (Table 1). The patients included 3 women and 17 men and their mean age at presentation was 41.2 years (range, 4 to 71 years).

The most common site was the superior sagittal sinus. In 15 out of the 20 cases, the superior sagittal sinus was injured. In 8 out of these 15 cases, the middle one-third of the superior sagittal sinus was injured, followed by injury to the anterior one-third of the superior sagittal sinus in 7 cases. In 4 cases, the transverse sinus was injured, and combined injury to the transverse and sigmoid sinus was noted in 1 case.

A linear skull fracture crossing the dural venous sinus was observed in 13 patients. Five patients had a linear skull fracture parallel to the sinus over the venous sinus. In two patients, a depressed skull fracture overlying the venous sinus was observed and one of them had a fracture penetrating the sinus based on CT findings.

In 11 out of the 13 patients with a linear skull fracture crossing the dural venous sinus, massive bleeding from the injured sinus wall could be controlled by simple digital pressure using Gelfoam. In two patients with a linear skull fracture crossing the dural venous sinus, there was vigorous bleeding from the sinus that could not be controlled by simple procedure. All 5 patients with a linear skull fracture parallel to the sinus over the venous sinus developed massive sinus bleeding that could not be controlled by simple digital pressure. Among them, one patient died due to hypovolemic shock following acute renal failure. In one patient with a depressed skull fracture overlying the sinus, the bleeding from the injured sinus could be controlled by simple procedure. In the other patient with a depressed skull fracture penetrating the dural venous sinus resulting in an abrasive lacerated sinus wall, the attempt to control hemorrhage from the injured sinus failed and he died due to hypovolemic shock.

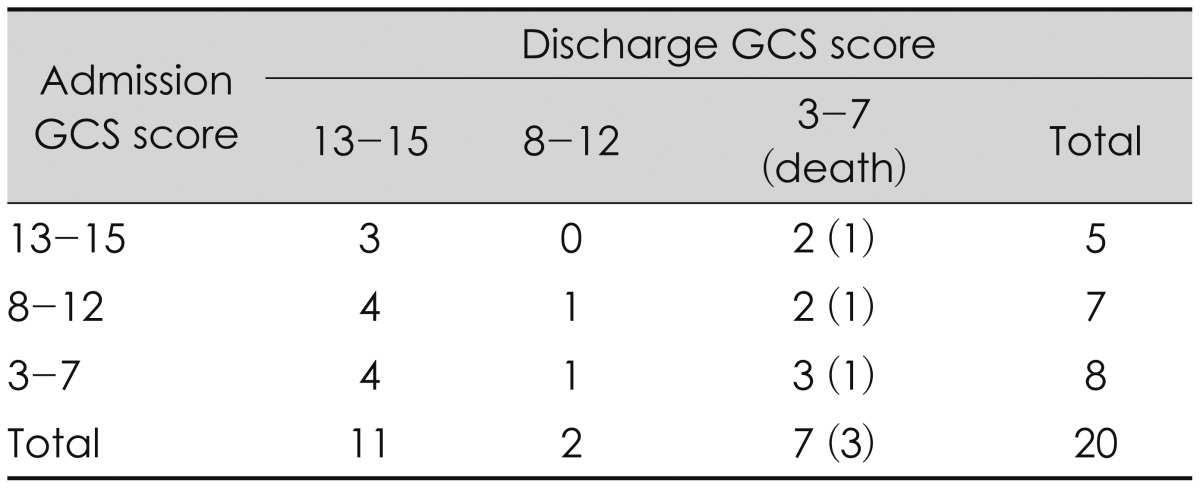

The neurological status at admission and discharge from the hospital were assessed using the GCS score. Table 2 shows the initial grading according to the GCS score compared to the outcome at discharge. These 20 patients had GCS scores at admission ranging from 4 to 14 (mean, 9.3). The neurological symptoms and signs at discharge from the hospital improved in 13 out of the 20 patients who underwent surgery, and 7 patients showed deterioration of neurological symptom and signs. In 7 patients, 4 patients were injured in the middle one-third of the superior sagittal sinus and 4 patients had a linear skull fracture parallel to the dural venous sinus.

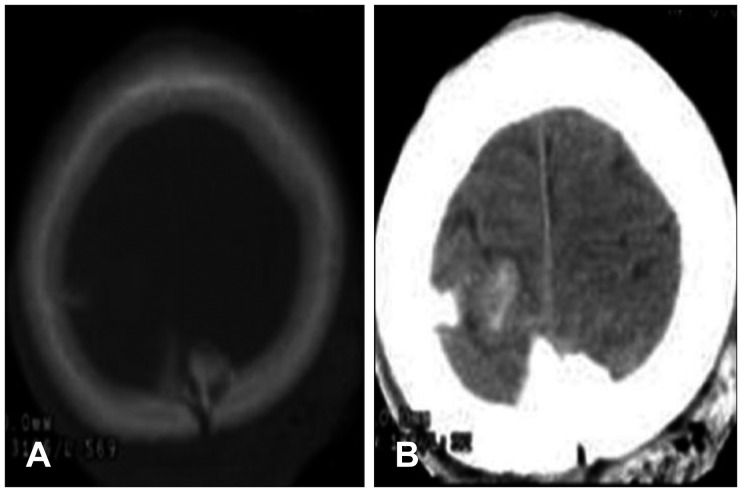

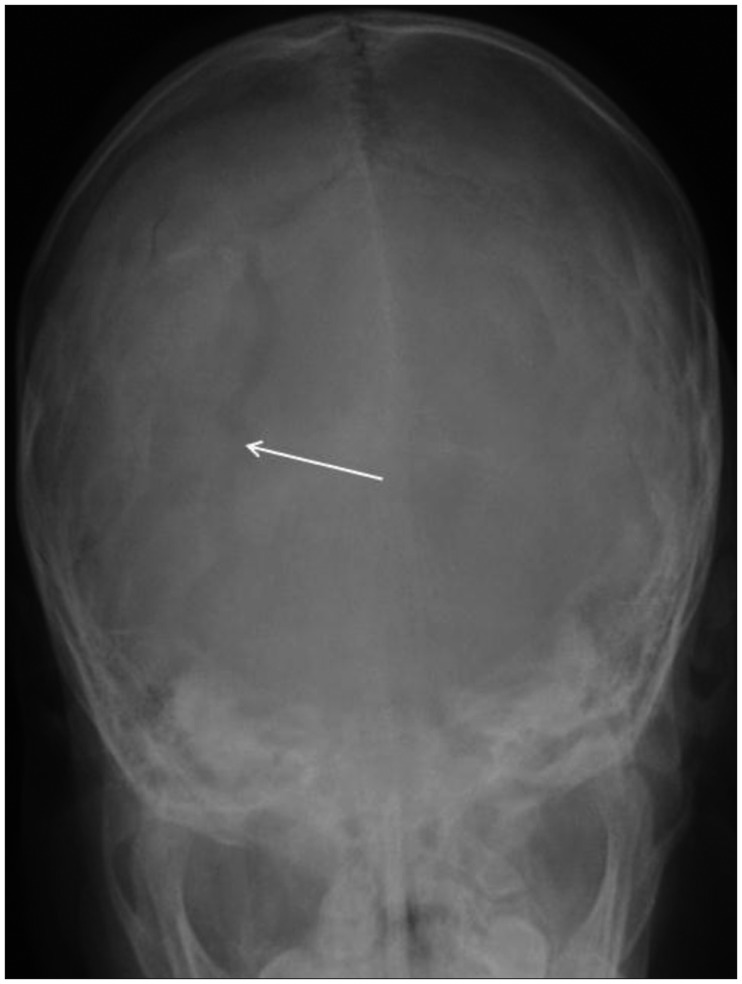

A 23-year-old man was hit in the head by a heavy iron pipe while working at a construction site. An ambulance transferred him immediately to our hospital. The patient did not suffer an initial loss of consciousness and did not show any neurologic deficit with a GCS score of E3 V5 M6 on admission. Plain X-ray and a CT scan demonstrated a compound depressed skull fracture penetrating the middle part of the superior sagittal sinus (Figure 1). There were signs of parenchymal abnormality including multiple hemorrhagic contusions, but no cerebral edema or midline shift. During conservative treatment, his mental status was worsened and his GCS score was down to E1 V1 M1. His continuously worsening mental status and profuse bleeding from the fracture necessitated an operation under general anesthesia. Open reduction and wound irrigation were performed. During the operation, we encountered massive bleeding from a 4 cm-sized complex longitudinal lacerated sinus after elevation of the bone fragments. Despite all efforts to control sinus bleeding, his systolic blood pressure (BP) dropped to 40 mm Hg and 12 units of packed red cells were transfused. The patient expired due to hypovolemic shock during postoperative care.

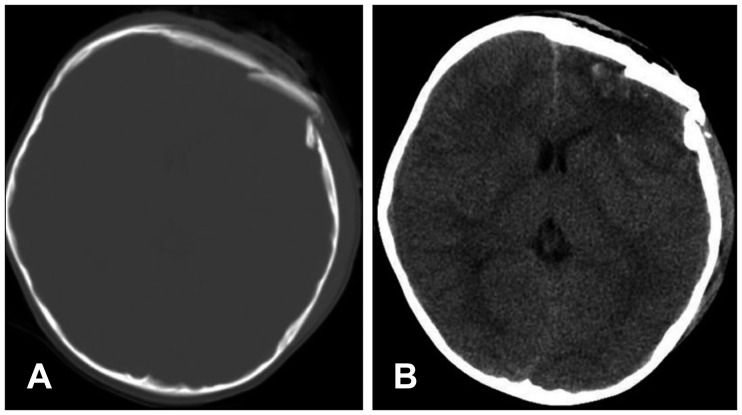

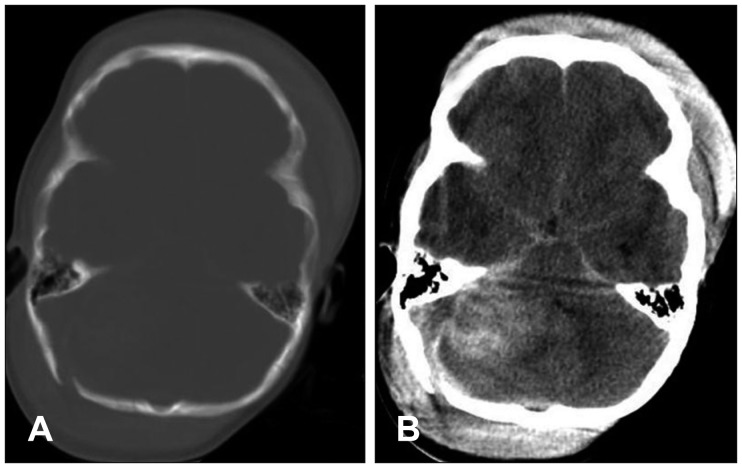

A 6-year-old boy was brought to the emergency department after being struck in the head during a traffic accident. His GCS score was E2 V2 M5 on admission. CT scan revealed an open compound depressed skull fracture overlying the anterior part of the superior sagittal sinus in the region of the left frontal bone with hemorrhagic contusions mainly in left frontal and temporal lobes and partially in the left parietal lobe (Figure 2). There was no midline shift. Emergency craniotomy and bony reconstruction were performed. At operation, we encountered massive bleeding from the lacerated sinus wall due to the fracture. Bleeding was stopped by simple digital pressure using Gelfoam and tenting. The patient fully recovered and his GCS score was 15 at discharge.

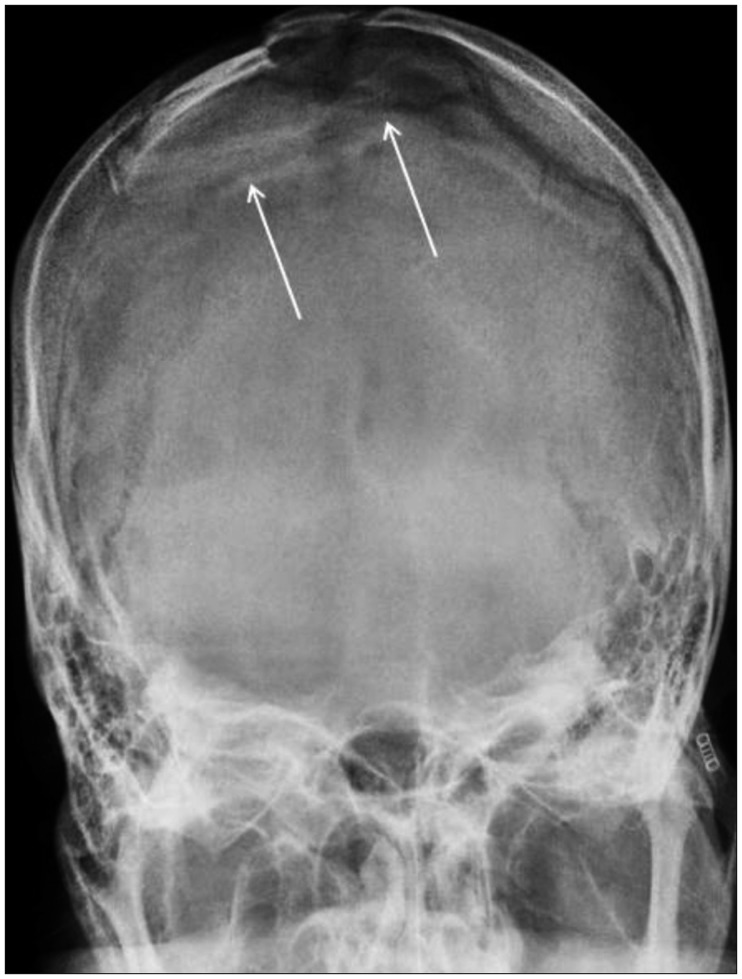

A 4-year-old girl who was injured in a traffic accident was transferred to our neurosurgical service. On arrival, her mental status was semicoma and she was given a GCS score of 7 (E1 V2 M4). Skull X-ray revealed a right occipital skull fracture parallel to the sigmoid sinus (Figure 3). CT of the brain showed a right posterior temporal and cerebellar epidural and subdural hematoma with mass effect and midline shift. It also revealed a skull fracture in the right occipital bone (Figure 4). Emergency right parieto-occipital craniotomy exposing the right supra- and infratentorial regions adjacent to the transverse and sigmoid sinus was performed. Immediately after scalp incision, we encountered massive bleeding and profuse bleeding was identified from the longitudinal lacerated wall of transverse and sigmoid sinus. During surgery, despite all efforts including Gelfoam packing and direct compression of the bleeding site to control the bleeding, the patient's BP dropped, and it could not be checked. The patient expired due to hypovolemic shock and acute renal failure.

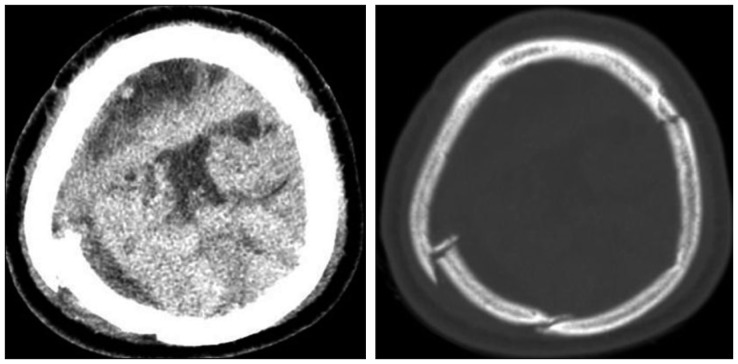

A 58-year-old male patient who sustained cranial trauma after falling down from a height of approximately 2 meters, was admitted to the emergency service. On admission to the hospital, the patient was intubated and he closed his eyes and demonstrated trace movements of all 4 extremities in response to painful stimuli. Skull X-ray showed multiple linear, depressed skull fractures of the vertex crossing the middle part of the superior sagittal sinus (Figure 5). Brain CT revealed a huge epidural hemorrhage along both high frontoparietal lobes with mass effect and midline shift (Figure 6). We considered fulminant sinus bleeding during the intraoperative period, but the hemorrhage from the injured sinus wall was stopped by simple digital pressure using Gelfoam. During the postoperative management, the patient fully recovered and he showed no neurological deficit.

Go to :

In the previous literature, the incidence of traumatic dural venous sinus injury ranges from 4% to 12% at the time of war, and from 1% to 4% in civilian life.3410) When this kind of injury occurs, surgeons face the problem of massive intraoperative blood loss and brain swelling secondary to venous stasis from occlusion of the major sinuses. Hence, the mortality rate associated with a sinus injury can increase to as high as 20% in the operative period and 41% overall. In our report, the incidence rate was 1.7%.

The most common site of dural venous sinus injury is the anterior and middle one-third of the superior sagittal sinus. Meier et al.,6) Meirowsky,7) Kapp and Gielchinsky,3) and Kapp et al.,4) reported that this same location has been noted in 66%, 57%, 74%, and 82% of the patients respectively. In our study, 75% of the patients had an injury in the anterior and middle one-third of the superior sagittal sinus. Location of sinus injury is very important in terms of perioperative mortality and morbidity. Because there is adequate collateral venous drainage associated with the tolerability for sinus injury or ligation, there is a decrease in mortality among patients with a sinus injury involving the anterior part of the superior sagittal sinus. Meier et al.6) reported that 17% of the patients with sinus injury in the anterior one-third of the superior sagittal sinus result in death, whereas 50% of the cases with injury at the middle one-third and all patients with injury to the posterior part of the superior sagittal sinus died. In our study, none of the patients with sinus injury involving the anterior part of the superior sagittal sinus died and 25% of the patients with injury at the middle part of the superior sagittal sinus and 20% of the patients with injury to the transverse sinus and sigmoid sinus died.

Multiple operative techniques have been used to control profuse bleeding from the injured sinus wall. Digital pressure with Gelfoam, dura, pericranium, temporal muscle or fascia is most frequently used simple method. Moreover, direct repair of defects on the sinus wall using simple suturing, hitching up the dura to the bone adjacent to the sinus, application of ligature around the rostral part, occlusion of the rostral part by clips, transplantation of an autologous vein, artificial sinus prosthesis, balloon catheter, and T-drainage have also been described.34) There was a recent report which suggested that application of tissue-glue-coated collagen sponge (TachoSil, Nycomed UK, Oxford, Buckinghamshire, UK) is also an effective surgical technique for repairing minor dural venous sinus laceration.2) Although various operative techniques are used in the treatment of sinus injury for stopping massive bleeding loss, there is a report in which blood loss from a lacerated dural venous sinus could be stopped with simple digital pressure in nearly all cases.9) However, in our study, although sinus bleeding could be stopped by mechanical pressure in most patients, two patients needed an extensive surgical approach, direct repair of laceration of the sinus wall using sutures.

Meier et al.6) reported that severe head injury and profuse bleeding are causes of intraoperative mortality and also of postoperative mortality to a great extent. Although a comparison of mortality rates associated with traumatic dural sinus injuries in the literature is difficult because of insufficient data from the case records and different time intervals between the accident and operation, mortality rates in patients with dural sinus injury reported in the literature range from 7% to 12% in patients without brainstem lesion.46) But, mortality rates increased to as high as 23% to 60% in patients with brain stem lesion.46) In our study, the overall mortality rate for twenty patients with dural sinus injury was 15%. Nine of the 20 patients had a GCS score of less than eight at admission in our hospital and three patients who developed uncontrolled sinus bleeding died intraoperatively.

Elevating depressed skull fractures overlying the superior sagittal sinus is considered hazardous. LeFeuvre et al.5) and Miller and Jennett8) reported that the incidences of severe hemorrhagic complications in patients undergoing operative treatment for depressed skull fractures over a venous sinus are 23% and 20%. Miller and Jennett8) also reported an incidence of 11.5% in cases with simultaneous penetration of a venous sinus. In such cases, conservative management is strongly emphasized because of the potential mortality resulting from uncontrollable bleeding. An open depressed skull fracture is usually repaired surgically and the dura is repaired as soon as possible to decrease the incidence of infection. However, in a closed depressed skull fracture, many authors recommend surgery only for 1 of the following 3 reasons: evacuation of a hematoma, repair of obviously lacerated dura (such as when large in-driven bone fragments are seen on CT), or for correction of a severe cosmetic deformity.11) But, standard textbooks on the subject rarely consider venous sinus injury caused by a closed depressed skull fracture as an indication for surgery. In one case (case 2), we considered conservative management initially. However, increased intracranial pressure in this patient accompanied by deteriorating neurologic condition necessitated surgical management. Finally, profuse uncontrollable bleeding occurred after removal of a fractured fragment perforating a venous sinus.

In addition to the skull fracture penetrating the dural venous sinus, when a linear skull fracture including diastatic skull fracture overlying the sinus is parallel to the sinus, it is possible that a longitudinal laceration of the venous sinus and uncontrollable vigorous hemorrhage from the lacerated sinus wall can occur. In our study, all 5 patients with a linear skull fracture parallel to the venous sinus developed massive sinus bleeding that could not be controlled by simple digital pressure and 2 patients among them died due to massive sinus bleeding. However, 11 out of the 13 patients with a skull fracture crossing the sinus developed sinus bleeding that could be controlled well by simple digital pressure.

Some authors reported that coagulopathy usually occurs due to massive transfusion after significant blood loss in patients with dural venous sinus injury. In a study by Behera et al.,1) thrombocytopenia occurred in 85% and defibrination occurred in 69% of cases with dural sinus injury. Hence, coagulation studies should be performed during the perioperative period. Furthermore, preoperative angiography can also be useful. Some authors have recommended that the venous sinus should be visualized by angiographic investigation before surgery.9) But, angiographic evaluation was not performed in our patients because of unsuitable conditions for emergency investigation.

Go to :

Our data shows that in many cases, massive bleeding from a lacerated dural venous sinus could be controlled with simple digital pressure. But, when there is a linear skull fracture parallel to the sinus over the dural venous sinus or a depressed skull fracture penetrating the sinus, the surgeon should be prepared for the potential fatal venous sinus injury, even in the absence of a hematoma.

Go to :

References

1. Behera SK, Senapati SB, Mishra SS, Das S. Management of superior sagittal sinus injury encountered in traumatic head injury patients: analysis of 15 cases. Asian J Neurosurg. 2015; 10:17–20. PMID: 25767570.

2. Gazzeri R, Galarza M, Fiore C, Callovini G, Alfieri A. Use of tissue-glue-coated collagen sponge (TachoSil) to repair minor cerebral dural venous sinus lacerations: technical note. Neurosurgery. 2015; 11 Suppl 2:32–36. discussion 36PMID: 25584959.

3. Kapp JP, Gielchinsky I. Management of combat wounds of the dural venous sinuses. Surgery. 1972; 71:913–917. PMID: 5030509.

4. Kapp JP, Gielchinsky I, Deardourff SL. Operative techniques for management of lesions involving the dural venous sinuses. Surg Neurol. 1977; 7:339–342. PMID: 882905.

5. LeFeuvre D, Taylor A, Peter JC. Compound depressed skull fractures involving a venous sinus. Surg Neurol. 2004; 62:121–125. discussion 125-126PMID: 15261501.

6. Meier U, Gärtner F, Knopf W, Klötzer R, Wolf O. The traumatic dural sinus injury--a clinical study. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1992; 119:91–93. PMID: 1481760.

8. Miller JD, Jennett WB. Complications of depressed skull fracture. Lancet. 1968; 2:991–995. PMID: 4176375.

9. Ozer FD, Yurt A, Sucu HK, Tektaş S. Depressed fractures over cranial venous sinus. J Emerg Med. 2005; 29:137–139. PMID: 16029821.

10. Rish BL. The repair of dural venous sinus wounds by autogenous venorrhaphy. J Neurosurg. 1971; 35:392–395. PMID: 5133588.

11. Steinbok P, Flodmark O, Martens D, Germann ET. Management of simple depressed skull fractures in children. J Neurosurg. 1987; 66:506–510. PMID: 3559717.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download