This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Traumatic intracranial pseudoaneurysms occurring after blunt head injuries are rare. We report an unusual case of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) caused by rupturing of the traumatic pseudoaneurysm of the internal carotid artery (ICA) bifurcation that resulted from a non-penetrating injury. In a patient with severe headache and SAH in the right sylvian cistern, which developed within 7 days after a blunt-force head injury, a trans-femoral cerebral angiogram (TFCA) showed aneurysmal sac which was insufficient to confirm the pseudoaneurysm. We obtained a multi-slab image of three dimensional time of flight (TOF) of magnetic resonance angiography (MRA). The source image of the gadolinium-enhanced MRA revealed an intimal flap within the intracranial ICA bifurcation, providing a clue for the diagnosis of a dissecting pseudoaneurysm at the ICA bifurcation due to blunt head trauma. We performed direct aneurysmal neck clipping, without neurological deficit. A follow-up TFCA did not show either aneurysm sac or luminal narrowing. We suggest that in the patient with a history of blunt head injury with SAH following shortly, multi-slab image of 3D TOF MRA can give visualization of the presence of a pseudoaneurysm.

Go to :

Keywords: Head injuries closed, Carotid artery injuries, Magnetic resonance angiography, Aneurysm false

Introduction

Traumatic intracranial aneurysms comprise 1% or less of all cerebral aneurysms. Regardless of the type of trauma, these pseudoaneurysms occur in association with significant morbidity, and the mortality rate is as high as 50%.

2,

4) The average time from initial trauma to aneurysmal rupture is approximately 21 days.

2,

3,

4,

5,

11,

13) An accurate, early diagnosis with appropriate treatment is vital for saving the patient's life.

We report, here, of a case of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) caused by the rupturing of a traumatic pseudoaneurysm in the internal carotid artery (ICA) bifurcation, which resulted from a blunt head injury. We confirmed the diagnosis of pseudoaneurysm through multi-slab image of 3D time of flight (TOF) of magnetic resonance angiography (MRA). The patient underwent a direct aneurysmal neck clipping, and no neurological sequelae were noted after the surgery.

Go to :

Case Report

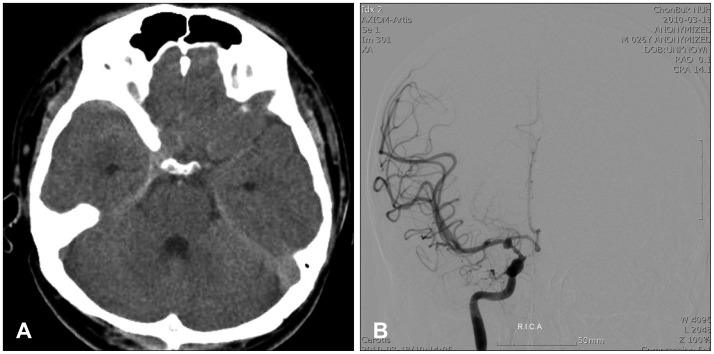

A 26-year-old man visited our medical center due to a severe headache and altered mental status. He had been healthy without any history of intracranial aneurysm or other medical and surgical history. His headache had lasted for 7 days, which started with a blunt head injury during snowboarding. Computed tomography (CT) upon his admission revealed a SAH in the right basal cistern and right sylvian fissure (

Figure 1A). A trans-femoral cerebral angiogram (TFCA) revealed luminal narrowing of the distal ICA, proximal middle cerebral artery, and aneurysmal sac in the right ICA bifurcation (

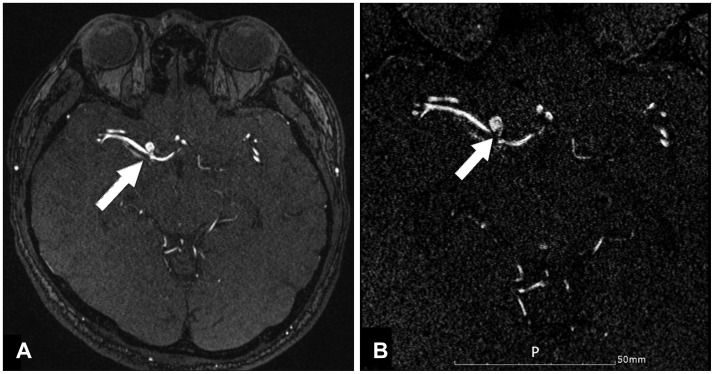

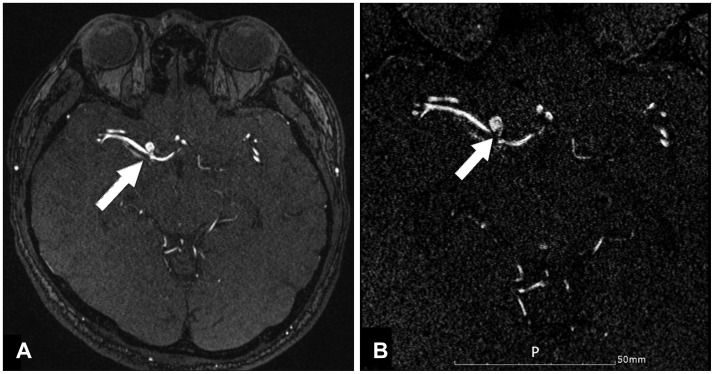

Figure 1B). The TFCA, however, could not definitively confirm the presence of a pseudoaneurysm. Therefore, we performed gadolinium (Gd)-enhanced 3D TOF MRA to reveal any evidence of a pseudoaneurysm (

Figure 2A). Resetting the parameters of the source images of Gd-enhanced 3D TOF MRA revealed an intimal flap within the aneurysm, with luminal narrowing of the distal ICA and proximal M1 (

Figure 2B). The parameters were as follows: TR 28 ms, TE 4.8 ms, flip angle 18°, matrix size 296×384, field of view 109×120 mm, slice thickness 0.29 mm, and scan time 4 min 39 sec.

| FIGURE 1A: Brain computed tomography image showing su-barachnoid hemorrhage in the right sylvian cistern. B: Trans-femoral cerebral angiogram showing luminal narrowing of distal internal carotid artery (ICA), proximal M1, and aneurysmal dilatation of right ICA bifurcation.

|

| FIGURE 2A: Initial source image of gadolinium-enhanced 3D time of flight image showing aneurysm of Rt. internal carotid artery bifurcation (white arrow). B: Resetting the initial image showing an intimal flap (white arrow) within the aneurysmal sac, suggesting of a pseudoaneurysm (parameters: TR 28 ms, TE 4.8 ms, flip angle 18°, matrix size 296×384, field of view 109×120 mm, slice thickness 0.29 mm, and scan time 4 min 39 sec).

|

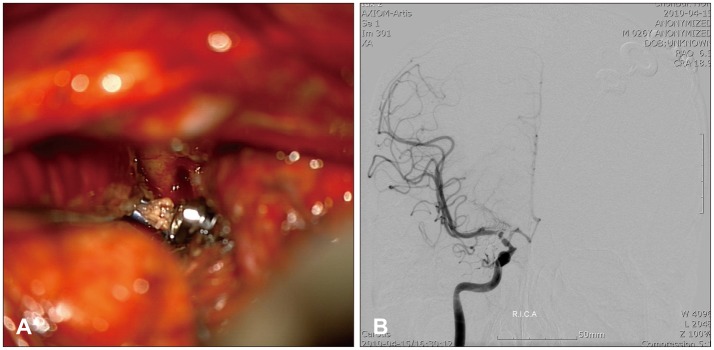

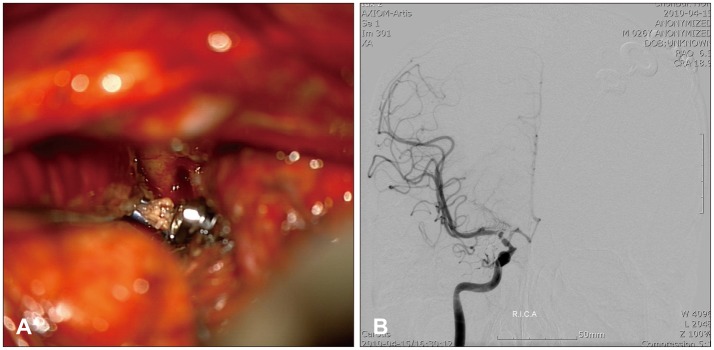

We concluded that his aneurysm must be a pseudoaneurysm due to the blunt head injury. The patient underwent direct aneurysmal neck clipping via a pterional approach (

Figure 3A). During the operation, we exposed the aneurysmal neck, and the rupture site border had full layer of the vessel; we eventually clipped one-third of the bifurcation site. No postoperative complications were noted, and the postoperative cerebral angiogram did not show any aneurysm or luminal narrowing (

Figure 3B).

| FIGURE 3A: Intraoperative findings, under microscopic guidance, of the direct neck clipping: the aneurysmal sac was larger than the preoperative evaluation suggested, and the wall was friable. B: Pos-toperative trans-femoral cerebral angiogram, showing no aneurysm and luminal narrowing.

|

Go to :

Discussion

Clinicians should consider the possibility of a pseudoaneurysm rupture in every case of a delayed neurological deterioration following any kind of head injury, because the mortality rate for untreated pseudoaneurysm cases is approximately 50%. Thus, the early and exact diagnosis with the appropriate treatment is very important to avoid an unexpected and fatal rupturing of the pseudoaneurysm.

8) Our patient showed delayed neurological deterioration, occurring 7 days after the blunt-force head injury with no visible contusion or hematoma on his head. Regarding the diagnostic modalities, the TFCA is the golden standard method. However, in our case, a TFCA revealed a round dome and a narrow neck, which are not specific to the diagnosis of pseudoaneurysm. To discern the presence of a pseudoaneurysm, we performed MRA which clearly showed an intimal flap.

The possible mechanism for the formation of the traumatic intracranial pseudoaneurysm are not fully understood.

14) Researchers propose several possible mechanisms for the formation of traumatic pseudoaneurysms, all of which involve either direct injury to the vessel or the stretching of the vessel by adjacent forces.

10) In the supraclinoid segment, the carotid artery transitions from a relatively fixed structure in the skull base and cavernous sinus to a relatively mobile structure as it ascends into the cisternal spaces. Researchers believe that either movement of the supraclinoid segment against the anterior clinoid process or stretching of the carotid artery at this transition zone leads to the formation of such an aneurysm,

7,

12,

13) and this mechanism apparently applies to our case.

Traumatic pseudoaneurysm occasionally regresses in size or spontaneously disappear,

7,

9,

11) but they also have a high incidence of rupturing. Therefore, surgery or endovascular treatment is necessary as soon as possible.

7)

Many techniques for traumatic pseudoaneurysm including clipping of the aneurysm, excision of the aneurysm with or without arterial bypass, trapping and interventional radiological techniques have been performed successfully. The surgery with direct neck clipping is difficult and dangerous due to the fragile characteristics and broad neck of pseudoaneurysm.

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6) Therefore, a widely-accepted surgical procedure is trapping or occluding the proximal ICA, with or without distal revascularization.

8) Therefore, for the safe and direct aneurysmal neck clipping, preoperative evaluation is important. Regarding the endovascular techniques for the treatment of this kind of aneurysm, directly embolizing the pseudoaneurysm is highly risky because of the false sac, and it will readily arouse bleeding during the intervention.

14) We can observe the characteristics of the pseudoaneurysm via multi-slab image of 3D TOF MRA, which consist of a narrow neck and the aneurysm's base appearing at the bifurcation with a relatively large luminal space; and a craniotomy and direct aneurysmal neck clipping can be performed safely. After the neck clipping, the aneurysmal sac collapsed and remained flat. Therefore, we were not able to perform the histopathological diagnosis. No postoperative neurological complications were reported from the patient.

Go to :

Conclusion

We suggest that when a patient with a history of blunt head injury presents with a SAH with a documented aneurysm, multi-slab imaging of Gd-enhanced 3D TOF MRA is helpful to determine the presence of an intimal flap and to confirm the pseudoaneurysm. In the case with a narrow neck and a relatively large luminal space of parent artery, direct aneurysmal neck clipping can be performed safely.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download