Abstract

Objectives

Heavy metals ingested through the consumption of aquatic products can accumulate in the human body over the long-term and cause various health problems. This study aims to present comprehensive data on the amount of heavy metals found in fish and shellfish in Korea using a systematic review of studies that report on that issue.

Methods

The study used the following databases: PubMed, Korean Studies Information Service System, and Research Information Sharing Service. The search terms for PubMed included fish OR shellfish OR seafood AND mercury OR cadmium OR lead OR heavy metal AND Korea. The search terms for Korean Studies Information Service System and Research Information Sharing Service included eoryu sueun, eoryu kadeumyum, eoryu nab, eoryu jung-geumsog, paeryu sueun, paeryu kadeumyum, paeryu nab, paeryu jung-geumsog, eopaeryu sueun, eopaeryu kadeumyum, eopaeryu nab, and eopaeryu jung-geumsog.

Results

A total of 32 articles were selected for review. The total mercury, lead, and cadmium concentrations in fish and shellfish reported in each of the articles are summarized, as are the species of fish and shellfish with relatively high concentrations of heavy metals. Total mercury concentrations tended to be higher in predatory fish species, such as sharks, billfishes, and tuna, while lead and cadmium concentrations tended to be higher in shellfish.

Due to heavy metal pollution across the globe, aquatic products contain heavy metals. Mercury (Hg), cadmium (Cd), and lead (Pb) are the primary heavy metals contained in aquatic products [1]. These heavy metals are reported to accumulate in living organisms [2] and cause various harmful health effects to humans such as neurophysiological dysfunction, kidney dysfunction, and decreases in bone mineral density, even at low concentrations [345]. Heavy metal contamination of aquatic products is transmitted to humans through food, so the heavy metal content of aquatic products has a significant impact on human health.

In Korea, 30% of all food containing protein and 80% of all animal proteins are consumed as aquatic products [6]. Aquatic products also contain various nutrients, such as selenium and omega-3 fatty acids [7]. However, since aquatic products are one of the largest sources of human exposure to hazardous heavy metals [1], there is a social concern about heavy metal contamination of marine products, and various studies have reported on the heavy metal concentrations in fish and shellfish.

Although several studies [689] have reported on the amount of heavy metals in fish and shellfish in Korea, it is difficult for researchers or the general public to obtain integrated information on the heavy metal content in fish and shellfish in Korea due to data is not found in one source.

Therefore, this study aims to present comprehensive data on the amount of heavy metals in fish and shellfish in Korea through a systematic review of studies that have investigated and reported on that issue.

To search for articles written in English and Korean, we conducted comprehensive database searches of the literature published from January 1998 to September 2017 using three databases: PubMed, Korean Studies Information Service System, and Research Information Sharing Service. The search terms for PubMed included fish OR shellfish OR seafood AND mercury OR cadmium OR lead OR heavy metal AND Korea. The search terms for Korean Studies Information Service System and Research Information Sharing Service included eoryu sueun, eoryu kadeumyum, eoryu nab, eoryu jung-geumsog, paeryu sueun, paeryu kadeumyum, paeryu nab, paeryu jung-geumsog, eopaeryu sueun, eopaeryu kadeumyum, eopaeryu nab, and eopaeryu jung-geumsog. The bibliographic records were imported, duplicates were removed, and the articles were screened to ensure that they met the inclusion criteria.

The titles and abstracts of the articles were screened by one investigator (SY) to ensure that they included English or Korean-language studies that reported original data on the three heavy metals (total Hg, Pb, and Cd) concentrations in fish and shellfish in Korea. Reviews were included at this level. Two investigators (SY and JS) independently screened the studies using exclusion criteria, and then they extracted the data. The following exclusion criteria were used to screen the articles: 1) did not report the three heavy metals concentrations; 2) heavy metal concentration unit is not convertible to ppm; 3) did not report the heavy metal concentration based on the type of fish and shellfish species; and 4) did not report the numbers or mean values of the analytical samples.

In the selected articles, the number of species samples examined, the means, the standard deviation, and the minimum and maximum values were extracted and summarized. After unifying the fish and shellfish species on the basis of Korean names, scientific names, or English names, the average of each heavy metal concentration in the same species was calculated from the data collected from several articles using the number of samples and mean values (formula 1). When recalculating the averages using formula 1, undetectable values were considered as zero.

After removing duplicate records, 398 bibliographic records were identified. Among these records, 345 articles did not meet the inclusion criteria at the first screening, 53 full-text articles were selected for full-text screening, and 32 articles were obtained and screened. Information about the searching and screening process, and the study inclusion criteria are summarized in the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram presented in Fig. 1.

Studies that examined the concentrations of three heavy metals, Hg, Pb, and Cd, in fish and shellfish in Korea are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. The number of samples analyzed, and the mean, standard deviation, and minimum and maximum values of the total Hg, Pb, and Cd concentrations in fish and shellfish reported in the selected literature are summarized in Supplementary Tables 2, 3, and 4, respectively. Of the 32 articles that reported on the concentrations of heavy metals in fish and shellfish, 15 reported Hg concentrations [101112131415161718192021222324], 12 reported heavy metal concentrations for Hg, Pb, and Cd [689252627282930313233], and 5 reported Pb and Cd concentrations [3435363738]. The mean values for each of the heavy metal concentrations for the same species were calculated using the data collected from several articles (Supplementary Tables 5, 6, 7).

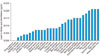

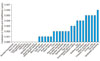

Figs. 2, 3, and 4 present information on 30 kinds of fish and shellfish with high total Hg, Pb, and Cd concentrations, respectively. The concentration of total Hg tended to be higher in predatory fish, such as sharks, billfishes, and tuna, while the concentrations of Pb and Cd tended to be higher in shellfish. The criteria for heavy metal concentrations in fish and shellfish used by the Korea Food and Drug Administration (KFDA) are as follows: total Hg concentration should be below 0.5 ppm for all fish and shellfish, except deep sea fish, tuna fish, and billfish. The concentration of methyl Hg in deep sea fish, tuna fish, and billfish should not exceed 1.0 ppm. All fish and shellfish should have Pb concentrations below 2.0 ppm, and the concentration of Cd should be 2.0 ppm or less in shellfish. After considering the concentration of methyl Hg in deep sea fish, tuna, and billfish as being 70% of the total Hg concentration [15], fish and shellfish with concentrations of heavy metals that exceed the KFDA standards were identified. Total Hg was higher than the KFDA standards in inshore hagfish and oil fish (Fig. 2). Concentrations of methyl Hg were higher than the KFDA standards in blue sharks, smooth hammerheads, shortfin mako sharks, crocodile sharks, and pelagic thresher sharks (Fig. 2). Concentrations of Pb and Cd were higher than the KFDA standard in Mediterranean mussels (Figs. 3, 4). Therefore, among the fish and shellfish with relatively high concentrations of heavy metals it is necessary to be particularly careful about consuming those that exceed the KFDA standards.

Figs. 5, 6, and 7 illustrate 30 kinds of fish and shellfish with low total concentrations of Hg, and low Pb and CD concentrations, respectively. Among the 30 kinds of fish and shellfish with low total concentrations of Hg, oysters and gizzard shads are known to contain high levels of omega-3 fatty acids (Fig. 5). Among the 30 kinds of fish and shellfish with low concentrations of Pb, river salmon and Coho salmon are known to contain high levels of omega-3 fatty acids (Fig. 6). Among the 30 kinds of fish and shellfish with low concentrations of Cd, Coho salmon is known to contain high levels of omega-3 fatty acids (Fig. 7).

The concentration of Hg was higher in predatory fish and the concentrations of Pb and Cd were higher in shellfish. Several types of fish and shellfish exceeded the KFDA heavy metal standards. Inshore hagfish and oil fish exceeded the KFDA standards for total Hg; blue sharks, smooth hammerheads, shortfin mako sharks, crocodile sharks, and pelagic thresher sharks exceeded the KFDA standards for methyl Hg; and Mediterranean mussel exceeded the KFDA standards for Pb and Cd. Thus, as the results of this study demonstrate, some types of fish and shellfish may be highly contaminated by heavy metals.

However, fish and shellfish also contain the most biologically active form of omega-3 fatty acids, docosahexaenoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid. Pacific saury, hairtail, chub mackerel, Spanish mackerel, anchovies, oysters, gizzard shad, Atka mackerel, salmon, Bluefin tuna, swordfish, and trout are known to contain high concentrations of omega-3 fatty acids [3940]. With the exception of Bluefin tuna and swordfish, which have high concentrations of Hg, hairtail, which has a high concentration of Pb, and oysters, which have high concentrations of Pb and Cd, the present study found that other types of fish were relatively low in heavy metals. According to the results of the study, salmon and gizzard shad had low concentrations of all three types of heavy metals. Consequently, the present study can be used as a basis for recommending foods with high nutrients and low concentrations of Hg, Pb, and Cd.

Of the papers that reported on the concentrations of heavy metals in fish and shellfish, most of the studies reported on Hg concentrations, while only a few reported on Pb and Cd concentrations. Fish and shellfish are major sources of Pb and Cd; therefore, further research is needed. In addition, further research on the levels of other contaminants, such as arsenic, methyl Hg, and endocrine disruptors, such as persistent organic pollutants, are also needed in the future.

This paper is the first to present a comprehensive summary of articles that investigated the concentrations of heavy metals (Hg, Pb, and Cd) in fish and shellfish. The findings could be used as evidence to protect Koreans from exposure to heavy metals due to the consumption of highly polluted aquatic products. The findings could also be useful for health researchers investigating the effects of exposure to heavy metals.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram of database search evidence and inclusion inclusion criteria. |

| Fig. 2Thirty types of fish and shellfish with high total mercury concentrations. *Sharks above the Korea Food and Drug Administration concentration standards for methyl mercury (1.0 ppm). †Fish above the Korea Food and Drug Administration concentration standards for total mercury (0.5 ppm). |

| Fig. 3Thirty types of fish and shellfish with high lead concentrations. *Shellfish above the Korea Food and Drug Administration concentration standards for lead (2.0 ppm). †The scientific name of the whelk is Neptuneaarthritica and the Korean name is Soragodung. ‡The scientific name of the whelk is Buccimon striatissimum and Korean name is Golbaeng-i. |

| Fig. 4Thirty types of fish and shellfish with high cadmium concentrations. *Shellfish above the Korea Food and Drug Administration concentration standards for cadmium (2.0 ppm). |

| Fig. 5Thirty types of fish and shellfish with low total mercury concentrations. *Fish and shellfish known to contain high levels of omega-3 fatty acids. |

References

1. Castro-Gonzalez MI, Mendez-Armenta M. Heavy metals: implications associated to fish consumption. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2008; 26:263–271.

2. Singh R, Gautam N, Mishra A, Gupta R. Heavy metals and living systems: an overview. Indian J Pharmacol. 2011; 43:246–253.

3. Zahir F, Rizwi SJ, Haq SK, Khan RH. Low dose mercury toxicity and human health. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2005; 20:351–360.

4. Needleman HL, Schell A, Bellinger D, Leviton A, Allred EN. The long-term effects of exposure to low doses of lead in childhood. An 11-year follow-up report. N Engl J Med. 1990; 322:83–88.

5. Satarug S, Moore MR. Adverse health effects of chronic exposure to low-level cadmium in foodstuffs and cigarette smoke. Environ Health Perspect. 2004; 112:1099–1103.

6. Hwang YO, Park SG. Contents of heavy metals in marine fishes, sold in Seoul. Anal Sci Technol. 2006; 19:342–351.

7. Park K, Mozaffarian D. Omega-3 fatty acids, mercury, and selenium in fish and the risk of cardiovascular diseases. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2010; 12:414–422.

8. Ha GJ. A study on the heavy metal content in fishes and shellfishes of Gyeongsangnam-do coastal area. Changwon: Changwon National University;2004.

9. Kim HY, Kim JC, Kim SY, Lee JH, Jang YM, Lee MS, et al. Monitoring of heavy metals in fishes in Korea: As, Cd, Cu, Pb, Mn, Zn, Total Hg. Korean J Food Sci Technol. 2007; 39:353–359.

10. Kang SH, Lee MJ, Kim JK, Jung YJ, Hur ES, Cho YS, et al. Contents of total mercury and methylmercury in deep-sea fish, tuna, billfish and fishery products. J Food Hyg Saf. 2017; 32:42–49.

11. Choi WS, Yoon MC, Jo MR, Kwon JY, Son KT, Kim JH, et al. Total mercury content and risk assessment of farmed fish tissues. Korean J Fish Aquat Sci. 2016; 49:7–12.

12. Kim SJ, Lee HK, Badejo AC, Lee WC, Moon HB. Species-specific accumulation of methyl and total mercury in sharks from offshore and coastal waters of Korea. Mar Pollut Bull. 2016; 102:210–215.

13. Jo M, Kim K, Jo M, Kwon J, Son K, Lee H, et al. Mercury contamination and risk evaluation in commonly consumed fishes as affected by habitat. Korean J Fish Aquat Sci. 2015; 48:621–630.

14. Yang HR, Kim NY, Hwang LH, Park JS, Kim JH. Mercury contamination and exposure assessment of fishery products in Korea. Food Addit Contam Part B Surveill. 2015; 8:44–49.

15. Kim JA, Yuk DH, Park YA, Choi HJ, Kim YC, Kim MS. A study on total mercury and methylmercury in commercial tuna, billfish, and deep-sea fish. Korean J Food Sci Technol. 2013; 45:376–381.

16. Choi H, Park SK, Kim M. Risk assessment of mercury through food intake for Korean population. Korean J Food Sci Technol. 2012; 44:106–113.

17. Kim CK, Lee TW, Lee KT, Lee JH, Lee CB. Nationwide monitoring of mercury in wild and farmed fish from fresh and coastal waters of Korea. Chemosphere. 2012; 89:1360–1368.

18. Park JS, Jung SY, Son YJ, Choi SJ, Kim MS, Kim JG, et al. Total mercury, methylmercury and ethylmercury in marine fish and marine fishery products sold in Seoul, Korea. Food Addit Contam Part B Surveill. 2011; 4:268–274.

19. Moon HB, Kim SJ, Park H, Jung YS, Lee S, Kim YH, et al. Exposure assessment for methyl and total mercury from seafood consumption in Korea, 2005 to 2008. J Environ Monit. 2011; 13:2400–2405.

20. Byeon MS, Lee JY, Park JJ, Shin SK, Han JS, Kim YH. Study on mercury concentrations of freshwater fish from lake An-dong and its upper stream. Anal Sci Technol. 2010; 23:492–497.

21. Joo H, Noh MJ, Yoo JH, Jang YM, Park JS, Kang MH, et al. Monitoring total mercury and methylmercury in commonly consumed aquatic foods. Korean J Food Sci Technol. 2010; 42:269–276.

22. Oh S, Kim MK, Yi SM, Zoh KD. Distributions of total mercury and methylmercury in surface sediments and fishes in Lake Shihwa, Korea. Sci Total Environ. 2010; 408:1059–1068.

23. Kim HY, Chung SY, Sho YS, Oh GS, Park S, Suh JH, et al. The study on the methylmercury analysis and the monitoring of total mercury and methylmercury in fish. Korean J Food Sci Technol. 2005; 37:882–888.

24. Oh KS, Suh J, Park S, Paek OJ, Yoon HJ, Kim HY, et al. Mercury and methylmercury levels in marine fish species Korean retail markets. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2008; 17:819–823.

25. Mok JS, Yoo HD, Kim PH, Yoon HD, Park YC, Lee TS, et al. Bioaccumulation of heavy metals in oysters from the southern coast of Korea: assessment of potential risk to human health. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 2015; 94:749–755.

26. Mok JS, Kwon JY, Son KT, Choi WS, Kang SR, Ha NY, et al. Contents and risk assessment of heavy metals in marine invertebrates from Korean coastal fish markets. J Food Prot. 2014; 77:1022–1030.

27. Jun JY, Xu XM, Jeong IH. Heavy metal contents of fish collected from the Korean coast of the East sea (Donghae). Korean J Fish Aquat Sci. 2007; 40:362–366.

28. Jeong JI, Min SS, Lee JS, In SW, Kim DW, Park YS, et al. A study on the analysis of harmful heavy metals in fishes and shellfishes from Korean coastal areas (II). Korean J Forensic Sci. 2003; 4:200–206.

29. Kim JH, Lim CW, Kim PJ, Park JH. Heavy metals in shellfishes around the South coast of Korea. J Food Hyg Saf. 2003; 18:125–132.

30. Kim M, Kim JS, Sho YS, Chung SY, Lee JO. The study on heavy metal contents in various foods. Korean J Food Sci Technol. 2003; 35:561–567.

31. Ham HJ. Distribution of hazardous heavy metals (Hg, Cd and Pb) in fishery products, sold at Garak wholesale markets in Seoul. J Food Hyg Saf. 2002; 17:146–151.

32. Sho YS, Kim J, Chung SY, Kim M, Hong MK. Trace metal contents in fishes and shellfishes and their safety evaluations. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr. 2000; 29:549–554.

33. Kim YC, Han SH. A study on heavy metal contents of the fresh water fish, and the shellfish in Korean. J Food Hyg Saf. 1999; 14:305–318.

34. Kim KH, Kim YJ, Heu MS, Kim JS. Contamination and risk assessment of lead and cadmium in commonly consumed fishes as affected by habitat. Korean J Fish Aquat Sci. 2016; 49:541–555.

35. Jeon MA, Kang JC, Lee JS. Contamination of heavy metal and alteration of reproductive and histological biomarker of Mytilus galloprovincialis in Gamak bay of the Southern coast of Korea. Korean J Malacol. 2013; 29:33–41.

36. Mok JS, Lee KJ, Shim KB, Lee TS, Song KC, Kim JH. Contents of heavy metals in marine invertebrates from the Korean coast. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr. 2010; 39:894–901.

37. Mok JS, Shim KB, Cho MR, Lee TS, Kim JH. Contents of heavy metals in fishes from the Korean coasts. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr. 2009; 38:517–524.

38. Hong TK, Hahm TS. Heavy metal concentrations in sediments and shellfish from western coast (Seosan, Taean). J Environ Res. 1999; 2:107–117.

39. Ahn BH, Shin HK. Fatty acid composition and content of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids of major fishes caught in Korean seas. Korean J Food Sci Technol. 1987; 19:181–187.

40. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. The reports of the dietary guidelines advisory committee on dietary guidelines for Americans [Internet]. Washington (DC): U.S. Department of Health & Human Services;c2005. cited 2017 Nov 01. Available from: https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2005/report/.

Supplementary material

Supplementary Tables are available from: https://doi.org/10.12771/emj.2018.41.1.1.

Supplementary Table 1

The reviewed studies that examined the concentrations of three heavy metals (Hg, Pb, Cd) in fish and shellfish

Supplementary Table 2

Mean, SD, Min, and Max values of the total Hg concentrations in fish and shellfish reported in the reviewed articles

Supplementary Table 3

Mean, SD, Min, and Max values of the Pb concentrations in fish and shellfish reported in the reviewed articles

Supplementary Table 4

Mean, SD, Min, and Max values of the Cd concentrations in fish and shellfish reported in the reviewed articles

Supplementary Table 5

Mean values of the total Hg concentrations calculated by species from the mean values reported in the reviewed articles

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download