Abstract

In order to examine the issue of women and health in Korean society, we need to adopt a new approach to consider health and body as a subject of social theory beyond the biomedical model. Health and diseases are not objective entities defined by universal standards that are separate from the patient or physician's life experience, but rather the products of social, cultural, and political processes. From this point of view, this paper explores Korean women and health in two aspects of health and medical field, that is, women as medical service beneficiaries and providers. First, the gender paradox phenomenon—women live longer, but suffer from more illnesses—was confirmed by evaluating the physical and mental health status of women. The life expectancy of Korean women is longer, but their morbidity rate of physical and mental health and subjective health evaluation is worse than men. Second, as medical service providers, the present status of female doctors showed the horizontal and vertical segregation in the medical labor market despite of the increase of female doctors and medical students. We pointed out the problems of gender inequality in health care sector and discuss policy implications of ‘gender specific medicine’ to improve women's health and medical education.

Figures and Tables

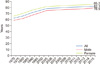

| Fig. 1Life expectancy by sex (1970–2015). Modified from Ministry of Health and Welfare [13]. |

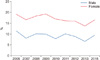

| Fig. 2Degree of stress (whether stress during the last 2 weeks) by sex. Modified from Ministry of Health and Welfare [13]. |

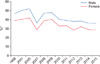

| Fig. 3Self-assessment of health by sex. *Percentage of respondents with very good and good self assessment of health. Modified from Ministry of Health and Welfare [16]. |

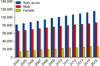

| Fig. 4Licensed physicians by sex: 2004–2015. Modified from Ministry of Health and Welfare [13]. |

Table 1

Morbidity rate, days of sickness and days in bed (during the previous 2 weeks, 0 years old and over)

Modified from Statistics Korea [15], p. 39.

Table 2

Types of employment among medical doctors by sex, 2014

Modified from Korean Medical Women's Association [26].

Table 3

Distribution of specialties among medical doctors by sex, 2014

Modified from Korean Medical Association [27], p. 85.

References

1. Scambler G, editor. Contemporary theorists for medical sociology. New York: Routledge;2012.

2. Cockerham WC. Medical sociology. 13th ed. Boston: Pearson;2015.

3. Berkman LF, Kawachi I, Glymour MM, editors. Social epidemiology. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press;2014.

4. Lupton D. Medicine as culture: illness, disease and the body. 3rd ed. London: Sage Publication;2012.

5. Cregan K. The sociology of the body. London: Sage Publication;2006.

6. Lee CW. Changes needed in the training and education of the increasing numbers of female medical students. Korean Med Educ Rev. 2011; 13:39–45.

7. Ahn JH. The influence of gender on professionalism female in trainees. Korean J Med Educ. 2012; 24:153–162.

8. Korea Medical School Council. Medical school yearbook 16. Seoul: Korea Medical School Council;2015.

9. Ly DP, Seabury SA, Jena AB. Differences in incomes of physicians in the United States by race and sex: observational study. BMJ. 2016; 353:i2923.

10. Hammarstrom A, Harenstam A, Ostlin P. Gender and health: concepts and explanatory models. In : Danielsson M, Diderichsen F, Harenstam A, Lindberg G, editors. Gender inequalities in health: a Swedish perspective. Boston: Harvard School of Public Health;2001. p. 1–22.

11. Mahowald MB. Bioethics and women: across the life span. New York: Oxford University Press;;2006.

12. Kuh D, Hardy R, editors. A life course approach to women's health. New York: Oxford University Press;2002.

13. Ministry of Health and Welfare. Ministry of Health and Welfare statistical year book 2016. Sejong: Ministry of Health and Welfare;2016.

14. Kontis V, Bennett JE, Mathers CD, Li G, Foreman K, Ezzati M. Future life expectancy in 35 industrialised countries: projections with a Bayesian model ensemble. Lancet. 2017; 389:1323–1335.

15. Statistics Korea. 2016 Report on the social survey. Daejeon: Statistics Korea;2016.

16. Ministry of Health and Welfare. National nutrition survey. Sejong: Ministry of Health and Welfare;2017.

17. Kim YT, Kim DS, Kim IS, Chung JJ. A study on the foreign cases for the strategies for promoting women's health policy in Korea. Seoul: Korean Women's Development Institute;2013.

18. Friedson E. The profession of medicine. Chicago: University of Chicago Press;1970.

19. Jacob JM. Doctors and rules: sociology of professional values. 2nd ed. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers;1999.

20. Light D. Counterveiling powers: a framework for professions in transition. In : Johnson T, Larkin G, Saks M, editors. Health professions and the states in Europe. London: Routledge;1995. p. 25–41.

21. Turner BS. Medical power and social knowledge. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press;1990.

22. Scott WR. Health care organizations in 1980s: the convergence of public and professional control system. In : Meyer JW, Scott WR, editors. Organizational environments: ritual and rationality. London: Sage Publication;1992. p. 99–113.

23. Cho BH. Korean doctors' crisis and survival strategy. Seoul: Myungkyung;1994.

24. Kim JS. An experimental study of medical education impact on the professionalism and social accountability among medical students. Health Soc Sci. 2002; 11:85–114.

25. Kim SH. The status of female doctors in Korean health institutions. Health Soc Sci. 2004; 16:89–130.

26. Korean Medical Women's Association [Internet]. Seoul: Korean Medical Women's Association;cited 2017 Jul 10. Available from: http://www.kmwa.or.kr.

27. Korean Medical Association. 2014 Annual report membership statistics Korean Medical Association. Seoul: Korean Medical Association;2015.

28. Lanska MJ, Lanska DJ, Rimm AA. Effect of rising percentage of female physicians on projections of physician supply. J Med Educ. 1984; 59:849–855.

29. Kletke PR, Marder WD, Silberger AB. The growing proportion of female physicians: implications for US physician supply. Am J Public Health. 1990; 80:300–304.

30. Brooks F. Women in general practice: responding to the sexual division of labour? Soc Sci Med. 1998; 47:181–193.

31. Riska E, Wegar K, editors. Gender, work and medicine: women and the medical division of labour. London: Sage Publication;2001.

32. Tsugawa Y, Jena AB, Figueroa JF, Orav EJ, Blumenthal DM, Jha AK. Comparison of hospital mortality and readmission rates for medicare patients treated by male vs female physicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2017; 177:206–213.

33. Legato MJ, Colman C. The female heart: the truth about women and heart disease. New York: Harper Collins;2000.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download