Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to explore the prevalence of bullying and to examine the effect of bullying on psychological well-being including depression, self-esteem, and academic major satisfaction among nursing students during clinical training.

Methods

Three hundreds one nursing students who were recruited from three universities in D City were assessed with self-report questionnaires of bullying experience and psychological well-being. Data analyses were performed using the SPSS 21.0 program, which included one-way ANOVA, independent t-test, Pearson's correlation, and multiple linear regression analyses.

Results

More than three quarters of the participants experienced bullying during their clinical training, and their experience of being bullied was a significant predictor of psychological well-being even after controlling for perceived academic performance, relationship between nurses and students, teachers' or nurses' help to deal with bullying, and religion.

Conclusion

Bullying was an issue among nursing students during clinical placement. Bullying experience yielded negative psychological outcomes associated with high depression, low self-esteem, and low academic major satisfaction. Practical guidelines are required in nursing education to protect students from the possible harm of bullying in clinical settings during training.

Bullying of healthcare workers has been a longstanding concern worldwide that extends far beyond a simple conflict between two individuals. Accumulated investigations provide evidence that staff nurses may be vulnerable to abuse, neglect, or violence in their workplaces across countries[1]. Bullying is not an issue that has been limited among healthcare workers. Approximately half of nursing students experienced verbal threats, racism or sexism and more than one third of them witnessed other students being bullied while gaining clinical experience [2]. Another study with 370 undergraduate nursing students in Turkey showed that 60% of them experienced bullying in clinical settings[3]. These findings reflected that nursing students should be considered as a risk group that might tend to be exposed to bullying during their clinical placement.

Bullying is defined as horizontal violence, interpersonal conflict, incivility, mobbing, and intimidation. It is also referred to as any act of aggression or hostility perpetrated by one person on others and can repeatedly occur in covert or overt ways over a period of time[4]. A study using a grounded theory identified three forms of bullying in nursing practice: between nurse and patient; between nurse and patient's significant other (s); and between nurse and nurse[5]. Bullying in the workplace appeared to have detrimental effects on occupational stress, staff turnover, and patient outcomes. Especially, workplace violence may lead to physical and emotional distress, lack of competence in clinical performance, reduced quality of care, and organizational burden to improve the safety for staff and patients[6].

The sentence "nurses eat their young" has been used to describe horizontal violence between senior and junior nurses in clinical settings[7]. From the hierarchical culture-based perspective of healthcare professions, nursing students are prone to become a target group of being bullied[4] because their status seem to be lower than junior nurses in this cultural context. It was suggested that lack of clinical experience and frequent ward changes were also associated with a decreased sense of control to adapt unfamiliar clinical environment and subsequent powerlessness, possibly leading to increased vulnerability to bullying in nursing students[8]. Due to a high risk of being bullied in clinical placement, nursing students may not be able to have a successful transition period from undergraduate students to healthcare professionals. According to Schlossberg's transition theory (1989), a transition was defined as "any event or nonevent that results in changed relationships, routines, assumptions, and roles about oneself and the world and thus requires a corresponding change in one's behavior (p. 27)"[9]. A successful transition depends on perceived balance of resources to deficits, such as a sense of competency[10]. Students who have experienced bullying showed lower competency of academic performance and achievement than others who were not bullied[11]. Taken together, students being bullied had negative outcomes in emotional, cognitive, and academic domains[12].

Psychological well-being was defined as a complex of cognitive and affective reactions to life experience and was evaluated with various instruments of self-esteem, locus of control, morale, mood (i.e., depression), and life satisfaction[13]. Psychological well-being has been conceptualized as depression, self-esteem, and life satisfaction. In a study to examine psychological well-being in Thai nursing students, psychological well-being was assessed with questionnaires to measure self-esteem, depression, social difficulties and life satisfaction [14]. Life satisfaction can be measured as job satisfaction for workers[15] or academic major satisfaction for college students[16]. Psychological well-being was treated as a combination of self-esteem, depression, and academic major satisfaction in this study, with consideration for special attributes of this type of well-being among college students.

Previous studies[231819] have been conducted to investigate the prevalence of bullying between nursing students and staffs and to examine the impact of bullying on occupational outcomes. However, there were no studies to examine the association between bullying experience and psychological outcomes in Korean nursing students. Based on Schlossberg's Transition Theory (1989), bullying was considered as an event that may yield negative psychological outcomes. This study aimed to explore bullying experience in nursing students during clinical placement and to examine factors associated with psychological well-being that was assessed as a combination of self-esteem, depression, and academic major satisfaction. The present study may provide useful knowledge that can be used to build a conceptual framework of bullying in Asian nursing students and suggest modifiable factors contributing to relevant interventions to improve psychological well-being in bullied students.

This study was designed as a descriptive, cross-sectional survey to examine the association of bullying experience and psychological well-being especially depression, self-esteem, and academic major satisfaction among college students at nursing schools. Participants were a convenience sample of 301 nursing students from 3 universities located in D city. All participants met the following eligibility criteria:(a) junior and senior nursing students who had clinical practices for at least 6 months, and (b) students who could speak Korean language. During the recruitment phase, 330 students were enrolled in this study. After their completed questionnaires were sent to the principal investigator, 29 of 330 students were excluded from analysis because of missing data about their bullying experiences and psychological well-being. Accordingly, the final sample consisted of 301 students.

The sample size for this study was calculated by power analysis with the G*Power program version 3.1. The needed sample size to have 80% power was calculated for multiple regression analysis including eleven independent variables with α of 0.05 two-tailed. This power analysis indicated a sample of 241 participants would sufficient to have 80% power and a minimal effect size of 0.1. Based on the sample size calculation, the current sample of 301 ensures an adequate number of subjects.

At the initial step of this study the authors obtained permission to use each self-reported questionnaire from original developers. After that, a principal investigator contacted potential participants and their instructors to receive their mutual consents and introduced the study to them prior to any data collection. Sufficient information about the purpose, procedure, data confidentiality, and the ethics of withdrawal from study participation were provided and then informed consent was obtained from all students who voluntarily decided to participate in this study. The survey packages including a cover letter, questionnaires, and a small gift were given to them. The principal investigator contacted study participants who did not return questionnaires within one week and encouraged them to send back their questionnaires. Data were collected from December 2013 to January 2014. The return rate was 91.2%. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Chungnam National University (IRB No. 2013-39).

Bullying experience was measured with the short version of the Negative Acts Questionnaire (NAQ). The original NAQ consisted of 23 items and each item ranged from 0 never to 4 daily[17]. The short version of NAQ was a 13-item instrument which was developed by Palaz [3] on the basis of studies with nursing students[1819]. This short version was translated into Korean using a standardized back translation technique with two healthcare professions who were bilingual in Korean as well as English. Additional modification was repeated until a consensus within the group for this translation project was reached. To examine the reliability and cultural relevance, a pilot study was conducted with 60 Korean nursing students who had participated in clinical placement programs for at least six months. Sufficient reliability (Cronbach's α= .89) of this measure was confirmed through this pilot study. Participants in the current study were asked how often they had been bullied during their clinical placement. Higher scores indicate a higher level of bullying. In order to explore the existence of bullying experience in participants, scores of the short version of NAQ were categorized as 1) 'no experience' which means scores=0 and 2) 'experience' which means scores ranging from 1 to 4. The Cronbach's α coefficients were higher than .80 on its development[3] and .89 in this study.

The Center for Epidemiology Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) was used to measure the level of depression. This scale is composed of 20 items and each item ranges from 0 never or rarely to 3 most of the time or all the time. The scores range from 0 to 60, with high scores indicating greater depressive symptoms. The CES-D Score of 16 was suggested as a cutoff score identifying individuals at risk for clinical depression[20]. The Cronbach's α of this scale was .89 on its development[21] and .90 in this study, showing acceptable reliability.

The Korean-translated Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale was administered to measure both positive and negative feelings about the self-esteem[22]. This scale consists of 10 items scored on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 strongly agree to 4 strongly disagree. Higher scores indicate better self-esteem. The Cronbach's α coefficients of the scale were higher than .80 in other studies[2324] and .88 in this study.

Nursing students' academic major satisfaction was measured with the Academic Major Satisfaction Scale (AMSS) developed by Nauta[16]. This scale includes 6 items that are administered using a five-point Likert scale. A higher score represents a student with higher academic major satisfaction and the Cronbach's α coefficient was .85 on its development[16], and .79 in this study.

General characteristics included gender, age, current year of study, religion, perceived academic performance, attending bullying management class, receiving any help from teachers or nurses to deal with bullying and relationship between nurses and students.

Data analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21.0. Prior to initiation of any statistical analyses, accuracy and completeness of all individual data were checked and confirmed. The participants' characteristics, bullying experience, and psychological well-being (i.e., depression, self-esteem, and academic major satisfaction) were described with frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviation. Comparative analyses including one-way analysis of variance and independent t-test were conducted to examine differences in depression, self-esteem, and academic major satisfaction according to participants' characteristics. The correlation coefficients among bullying experience, depression, self-esteem, and academic major satisfaction were computed by using the Pearson's correlation. Multiple regression analyses were performed to examine associating factors of psychological well-being.

As presented in Table 1, most participants in this study were female (89.37%). 175 (58.14%) were junior nursing students and 166 (55.15%) participants did not have any religion. About 80% of participants reported that their perceived academic performance was high (32.89%) or medium (47.51%). More than half of the students (67.77%) did not attend bullying management class and 59.80% of students did not receive any help from teachers or nurses in dealing with bullying experience. Only 26.91% of students reported that their relationships with nurses were good.

230 students (76.41%) reported that they had experienced at least one bullying behavior in the past six months. The frequency of each bullying behavior experienced by nursing students was detailed in Table 2. Specifically, the frequent types of bullying included inappropriate, nasty, rude, or hostile behavior (48.84%), belittling or humiliating behavior (39.20%), negative or disparaging remarks about nursing profession (38.21%), cursing or swearing (37.87%), yelling or shouting in rage (36.21%), and assignments made for punishment (27.57 %). Bullying behaviors were divided into verbal bullying behaviors and academic bullying behaviors in accordance with the suggestion by Celik and Bayraktar [19]. Notably, this study result showed that verbal bullying behaviors (i.e., inappropriate, nasty, rude, or hostile behavior, belittling or humiliating behavior, cursing or swearing, and yelling or shouting in rage) were experienced more frequently than academic bullying (i.e., assignments made for punishment and negative or disparaging remarks about nursing profession).

The CES-D Score of 16 or higher was considered depressed[20]. in this study, the mean of the CES-D was 18.32 (SD=10.01), indicating a high prevalence (64.78%) of depression in nursing students. The overall score on self-esteem was 29.55±4.45 and the average score on AMSS was 21.81±4.16. As seen in Table 3, psychological well-being including depression (r=.19, p=.001), self-esteem (r=-.21, p<.001), and academic major satisfaction (r=-.18, p=.003) was significantly related to bullying experience during clinical training. In addition, it was found that the level of psychological well-being was different depending on having religion, perceived academic performance, teacher/nurse's help to deal with bullying, and relationship between nurses and students. Specifically, depressive symptom scores differed significantly depending on perceived academic performance (P<.001), teacher/nurse's help to deal with bullying (p=.026), and relationship between nurses and students (p=.049). Self-esteem was significantly associated with having religion (p=.028), perceived academic performance (P<.001), teacher/nurse's help (p=.010), and relationship between nurses and students (p=.003). Academic major satisfaction was significantly associated with differences in perceived academic performance (P<.001) (Table 4).

Multiple regression analyses were performed to determine the possible predictors of psychological well-being. Based on comparative and correlational analyses, bullying score and four characteristics including having religion, perceived academic performance, teachers/nurses' help, and nurse-student relationship were selected as independent variables for the regression models(Table 5). In our study, the VIF values ranged from 1.03 to 4.30 and the tolerance values ranged from 0.23 to 0.97 for all three models. A cook distance of greater than 1 was not found in any models, indicating the absence of outliers in each regression model. The Durban-Watson statistics were within the acceptable range (1.48~1.65). The standardized residuals were normally distributed according to the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (p=.200). These findings indicated no serious issues about the assumptions of multicollinearity, homoscedasticity, and normal distribution of residuals.

Bullying score, perceived academic performance, and nurse-student relationship were found to be significant predictors of depression, accounting for 11% of the variance in depression, Multiple R=0.34, F7,293=5.33, P< .001. Specifically, students with lower score on bullying, a high level of perceived academic performance, and a good nurse-student relationship had lower depression. The same factors also significantly explained the variance in self-esteem, R2=0.19, Multiple R=0.44, F7,293=9.90, P<.001. Lower score on bullying, a high or middle level of perceived academic performance, and a good nurse-student relationship were significantly correlated with better self-esteem. Only two variables, bullying and perceived academic performance, were found to be significant predictors of academic major performance, indicating that the R2 was 0.10, Multiple R=0.31, F7,293=4.44, P<.001. Higher academic major satisfaction was associated with lower score on bullying (p=.023) and a high level of perceived academic performance (P<.001). Taken together, students with less bullying experience and a high level of perceived academic performance had better psychological well-being.

The present study was a first to describe bullying experience and to investigate factors associated with psychological well-being defined as a combined concept of depression, self-esteem, and academic major satisfaction among Korean nursing students who have been trained through diverse clinical placements for at least six months. Findings of this study revealed that nursing students experienced a high frequency of being bullied. About 76.41% of participants in this study reported that they had experienced bullying in clinical settings. This result was higher than that reported by Celik and Bayraktar[19] showing that 60% of students had experienced bullying but lower than results of previous studies that showed bullying experience in 90% of nursing students in the United States[18] and 91% of nursing students in Korea[25].

Regardless of various occurrence rates of bullying, these findings suggested that more than half of nursing students might be bullied during their clinical placements. There is a possible way to explain the existence of bullying in healthcare settings. Nurses were an oppressed group in male-dominant occupational environments so they tended to dissolve their own suffering associated with their powerlessness through bullying young coworkers or subordinates[26]. In the same way, nursing students came to become a target of bullying because of lack of professional experience and ability to deal with conflicts in clinical settings[4825]. Also, nursing students were likely to assimilate bullying into their nursing practice as they were silent about this painful experience[25]. In collectivistic societies such as East Asian countries interpersonal harmony, courtesy, and self-restraint have been suggested as the important cultural virtues for maintaining a good relationship between superiors and subordinates[23]. The culturally preferred social etiquette may influence the awareness, perception, and interpretation about abusive experience during clinical placement, leading to culture of tolerating bullying.

Findings of this study showed lower levels of psychological well-being among nursing students participated in this study. Specifically, 64.8% of participants reported experiencing a serious level of depressed mood with higher scores than that in a study with Korean college students[23]. The average scores for self-esteem (29.6) and academic major satisfaction (21.8) reported in this study were lower than those reported in non-Korean studies with nursing students having average score of 31.5 for self-esteem and 25.6 for academic major satisfaction[1416]. Similarly, nursing students of this study showed lower self-esteem than non-nursing college students in Korea[23]. Although this study did not explain why the participants showed low levels of psychological well-being, a possible explanation could be extracted from socially accepted values associated with the idiom of distress that reflects cultural meanings of suffering. Asian culture tends to emphasize stoicism including self-control, self-restraint, and self-sacrifice through the idea that people should suppress personal feelings and behaviors in sustaining harmony within hierarchical groups [27]. Likewise, self-sacrifice has been found as a virtue required to carry out professional responsibilities for patient well-being although it was pointed out that stoicism was a tradition that might interfere with professional development in nursing[28]. Based on these comparisons and the above-mentioned explanation, it is possible to say that Korean nursing students may be frequently encountered with culture-specific and/or major-related pressure that can raise negative psychological responses.

This study showed that nursing students who experienced more bullying reported higher levels of depression, lower scores of self-esteem, and lower academic major satisfaction. Psychological well-being was mainly associated with bullying, perceived academic performance, relationship between nurses and students with 11 %, 19% and 10% of the variance in depression, self-esteem, and academic major satisfaction, respectively. These results were consistent with a study showing the significant correlation between the existence of bullying and low self-esteem[24]. Kivimäki et al.,[29] also found that the effect of prolonged exposure to bullying was related with subsequent depression even when controlling for sex, age, and income . Based on findings of other studies, it can be suggested that nursing students may experience bullying through unhealthy relationships with nursing instructors or staffs in hospitals for clinical placements and subsequent stress induced by bullying experiences may result in psychological well-being[18], which can lead to reduced satisfaction and their future intentions to keep their job[30]. Other characteristics were also found as important factors of psychological well-being. That is, students who perceived their academic performance as a high level and had good nurses-students relations reported higher levels of psychological well-being. According to the transition theory by Schlossberg (1989), bullying may interfere with a successful transition, possibly due to lack of resources to manage stressful situations, and thus fail to maintain good psychological outcomes and the integration of new relationships, duties, and roles into daily routines[9]. In order to improve psychological well-being in nursing students, it may be needed to develop interventions targeting at least three different factors, especially the exposure to bullying during clinical placements, lack of resource to effectively respond to stressors, and psychological problems. Furthermore, to establish a knowledge foundation with a deep understanding it is needed to explore other antecedent factors of psychological well-being in nursing students who might experience bullying during clinical placements and to perform a causal modeling approach such as structural equation modeling based on the transition theory.

There were two limitations in this study. First, the study was performed with nursing students from 3 nursing universities in Korea so the findings cannot be generalized to all Korean nursing students. Second, this study used a cross-sectional design. To decipher the effect of long-term bullying experiences on changes in psychological well-being, a longitudinal prospective design should be conducted in future research. Despite these limitations, the current study provided several implications for nursing education and clinical practicum. The findings can be used to develop educational programs for students, clinical instructors, and nurses to enhance awareness of bullying behaviors and management in terms of response and adverse outcomes. Furthermore, nurse administrators can utilize these findings to establish policies that create a bully-free culture with supportive and communicative environment in work places.

This study revealed that bullying was an issue among nursing students during clinical placement. Bullying experience yielded negative psychological outcomes associated with high depression, low self-esteem, and low academic major satisfaction. Bullying and perceived academic performance were important factors of psychological well-being. Practical guidelines are required in nursing education to protect students from the possible harm of bullying in clinical settings during training. Furthermore, this finding can be applied to develop educational programs for promoting awareness of bullying behaviors and inappropriate coping mechanisms in nursing students during clinical training.

Figures and Tables

Table 1

Characteristics of Participants (N=301)

Table 2

Frequencies of Bullying Behaviors Experienced by Nursing Students

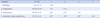

Table 3

Relationship among Bullying and Psychological Well-being

| Variables | M±SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Bullying | 5.24±6.74 | 1.00 | |||

| 2. Depression | 18.32±10.01 | .19* | 1.00 | ||

| 3. Self-esteem | 29.55±4.45 | -.21** | -.64** | 1.00 | |

| 4. Academic major satisfaction | 21.81±4.16 | -.18* | -.26** | .39** | 1.00 |

Table 4

Differences in Psychological Well-being according to Characteristics of Participants

Table 5

Predictors of Psychological Well-being

References

1. Johnson SL. International perspectives on workplace bullying among nurses: A review. Int Nurs Rev. 2009; 56(1):34–40. DOI: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2008.00679.x.

2. Ferns T, Meerabeau L. Verbal abuse experienced by nursing students. J Adv Nurs. 2008; 61(4):436–444. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04504.x.

3. Palaz S. Turkish nursing students' perceptions and experiences of bullying behavior in nursing education. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2013; 3(1):23–30. DOI: 10.5430/jnep.v3n1p23.

4. Longo J, Sherman RO. Leveling horizontal violence. Nurs Manage. 2007; 38(3):34–37. DOI: 10.1097/01.NUMA.0000262925.77680.e0.

5. Farrell GA. Aggression in clinical settings: Nurses' views-a follow-up study. J Adv Nurs. 1999; 29(3):532–541. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.00920.x.

6. Etienne E. Exploring workplace bullying in nursing. Workplace Health Saf. 2014; 62(1):6–11. DOI: 10.3928/21650799-20131220-02.

8. Ferns T, Meerabeau E. Reporting behaviours of nursing students who have experienced verbal abuse. J Adv Nurs. 2009; 65(12):2678–2688. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05114.x.

9. Schlossberg NK, Lynch AQ, Chickering AW. Improving higher education environments for adults: Responsive programs and services from entry to departure. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc;1989. p. 281.

10. Schlossberg NK. A model for analyzing human adaptation to transition. Couns Psychol. 1981; 9(2):2–18. DOI: 10.1177/001100008100900202.

11. Brown EC, Low S, Smith BH, Haggerty KP. Outcomes from a school-randomized controlled trial of steps to respect: A bullying prevention program. School Psych Rev. 2011; 40(3):423–433.

12. McDaniel KR, Ngala F, Leonard KM. Does competency matter? Competency as afactor in workplace bullying. J Manage Psychol. 2015; 30(5):597–609. DOI: 10.1108/JMP-02-2013-0046.

13. Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989; 57(6):1069–1081. DOI: 10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069.

14. Ratanasiripong P, Wang CC. Psychological well-being of Thai nursing students. Nurse Educ Today. 2011; 31(4):412–416. DOI: 10.1016/j.nedt.2010.08.002.

15. Warr P, Cook J, Wall T. Scales for the measurement of some work attitudes and aspects of psychological well-being. Occup Psychol. 1979; 52(2):129–148. DOI: 10.1111/j.2044-8325.1979.tb00448.x.

16. Nauta MM. Assessing college students' satisfaction with their academic majors. J Career Assess. 2007; 15(4):446–462. DOI: 10.1177/1069072707305762.

17. Einarsen S, Raknes BI. Harassment in the workplace and the victimization of men. Violence Vict. 1997; 12(3):247–263.

18. Cooper JR, Walker J, Askew R, Robinson JC, McNair M. Students' perceptions of bullying behaviours by nursing faculty. Issues Educ Res. 2011; 21(1):1–21.

19. Celik SS, Bayraktar N. A study of nursing student abuse in Turkey. J Nurs Educ. 2004; 43(7):330–336.

20. Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977; 1(3):385–401. DOI: 10.1177/014662167700100306.

21. Cho MJ, Kim G. Clinical properties of CES-D among depressive symptoms patients. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 1993; 32(3):381–397.

22. Jeon BJ. Self-esteem: A test of its measurability. Yonsei Nonchong. 1974; 11:107–130.

23. Ha JY. Drinking problems, stress, depression and self-esteem of university students. J Korean Acad Adult Nurs. 2010; 22(2):182–189.

24. Iglesias ME, Vallejo BR. Prevalence of bullying at work and its association with self-esteem scores in a Spanish nurse sample. Contemp Nurse. 2012; 42(1):2–10. DOI: 10.5172/conu.2012.42.1.2.

25. Park J. Nursing student's experience, their response and coping method of violence. [dissertation]. Busan: Pusan National University;2013. 162.

26. Cleary M, Hunt GE, Walter G, Robertson M. Dealing with bullying in the workplace: Toward zero tolerance. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2009; 47(12):34–41. DOI: 10.3928/02793695-20091103-03.

27. Cho GH. The confucian origin of the east Asian collectivism. Korean J Soc Pers Psychol. 2007; 21(4):21–54.

28. Scott H. Stoicism does not make nursing a profession. Br J Nurs. 2001; 10(11):696.

29. Kivimaäki M, Virtanen M, Vartia M, Elovainio M, Vahtera J, Keltikangas-Jaärvinen L. Workplace bullying and the risk of cardiovascular disease and depression. Occup Environ Med. 2003; 60(10):779–783. DOI: 10.1136/oem.60.10.779.

30. Topa G, Guglielmi D, Depolo M. Mentoring and group identification as antecedents of satisfaction and health among nurses: What role do bullying experiences play? Nurse Educ Today. 2014; 34(4):507–512. DOI: 10.1016/j.nedt.2013.07.006.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download