Abstract

Purpose

The purposes of the study were to investigate childhood traumatic experiences and social support that might influence dissociative symptoms in Marine soldiers.

Methods

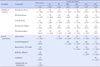

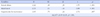

A cross-sectional study design was used with participants who were soldiers (n=122) assigned to one Marine corps in Ganghwa Island in the study. Data were collected on September 2015 through self-report using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, Social Provisions Scale (SPS), and Dissociative Experience Scale. Descriptive analysis, t-test, ANOVA, Pearson's correlation coefficients and stepwise multiple regression were performed.

Results

A total of 11.5% self-reported experiencing over three types of trauma; emotional neglect 34.4%, physical neglect 32.8%, emotional abuse 11.5%, physical abuse 11.5%, and sexual abuse 9.8%. For all subscales of the SPS, means of item were as high as three out of four points. A total of 9.0% were likely to be dissociative disorder. Sexual abuse, attachment, and opportunity for nurturance were found to be significant factors influencing dissociative symptoms.

Conclusion

Future military enlistment in Marines should include assessment of childhood trauma and dissociation to identify maladaptive soldiers. Because soldiers who experienced childhood sexual abuse are likely to show dissociative symptoms, military nurses should assess their social support and try to enhance attachment in order to prevent dissociative symptoms.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Seo HS, Kim JE, Shin HK. A study on effectiveness of transactional analysis group counselling on marine corps military life adjustment. Korean J Psychodrama. 2014; 17(2):123–139.

2. Cozolini L. The neuroscience of human relationships: attachment and the developing social brain. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company;2006.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th text revision ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association;2013. DOI: 10.1007/springerreference_179660.

4. Taylor MK, Morgan CA 3rd. Spontaneous and deliberate dissociative states in military personnel: relationships to objective performance under stress. Mil Med. 2014; 179(9):955–958. DOI: 10.7205/milmed-d-14-00081.

5. Özdemir B, Celik C, Oznur T. Assessment of dissociation among combat-exposed soldiers with and without post traumatic stress disorder. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2015; 28(6):26657. DOI: 10.3402/ejpt.v6.26657.

6. Herman J. Trauma and recovery: the aftermath of violencefrom domestic abuse to political terror. New York: Basic Books;1997. DOI: 10.1097/00005053-199308000-00018.

7. Youssef NA, Green KT, Dedert EA, Hertzberg JS, Calhoun PS, Dennis MF, et al. Exploration of the influence of childhood trauma, combat exposure, and the resilience construct on depression and suicidal ideation among U.S. Iraq/Afghanistan era military personnel and veterans. Arch Suicide Res. 2013; 17(2):106–122. DOI: 10.1080/13811118.2013.776445.

8. Jeong SB. The trauma experience, anxiety, depression, and military adaptation of enlisted soldiers [master's thesis]. Daegu: Kyungpook National University;2013. 47.

9. Mulder RT, Beautrais AL, Joyce PR, Fergusson DM. Relationship between dissociation, childhood sexual abuse, childhood physical abuse, and mental illness in a general population sample. Am J Psychiatry. 1998; 155(6):806–811.

10. Barahmand U, Hozoori R. A study of alexithymia and dissociative experiences in soldiers and male university students. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2013; 84(9):165–170. DOI: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.529.

11. Ozbay F, Johnson DC, Dimoulas E, Morgan CA, Charney D, Southwick S. Social support and resilience to stress: from neurobiology to clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2007; 4(5):35–40. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/20806028.

12. Evans SE, Steel AL, DiLillo D. Child maltreatment severity and adult trauma symptoms: does perceived social support play a buffering role? Child Abuse Negl. 2013; 37(11):934–943. DOI: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.03.005.

13. Welsh JA, Olson J, Perkins DF, Travis WJ, Ormsby L. The role of natural support systems in the post-deployment adjustment of active duty military personnel. Am J Community Psychol. 2015; 56(1-2):69–78. DOI: 10.1007/s10464-015-9726-y.

14. Bernstein DP, Fink L. Childhood trauma questionnaire: a retrospective self-report, Korean translation version. SanAntonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation;1998.

15. Cutrona CE, Russell DW. Advances in personal relationships. In : Jones WH, Perlman D, editors. The provisions of social relationships and adaptation to stress. Greenwich, Conn: JAI Press;1987. p. 37–67. .

16. Yoo YR, Lee JY. Adult attachment and help-seeking intention: the mediating roles of self concealment, perceived social support, and psychological distress. Korean J Clin Psychol. 2006; 18(2):441–460.

17. Bernstein EM, Putnam FW. Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1986; 174:727–735. DOI: 10.1037/e609912012-081.

18. Park JM, Choe BM, Kim M, Han HM, Yoo SY, Kim SH, et al. Standardization of dissociative experience scale-Korean version. Korean J Psychopathol. 1995; 4:105–125.

19. Carlson EB, Putnam FW. An update on the dissociative experiences scale. Dissociation. 1993; 6:16–27. http://hdl.handle.net/1794/1539.

20. Perales R, Gallaway MS, Forys-Donahue KL, Spiess A, Millikan AM. Prevalence of childhood trauma among U.S. Army soldiers with suicidal behavior. Mil Med. 2012; 177(9):1034–1040. DOI: 10.7205/milmed-d-12-00054.

21. Rosen LN, Martin L. Impact of childhood abuse history on psychological symptoms among male and female soldiers in the U.S. Army. Child Abuse Negl. 1996; 20(12):1149–1160.

22. Hunter WM, Cox CE, Teagle S, Johnson RM, Mathew R, Knight ED, et al. Measures for assessment of functioning and outcomes in longitudinal research on child abuse. 2003. LONGSCAN web site (http://www.iprc.unc.edu/longscan/).

23. Kim YE. The impact of army soldier's parent attachment on military life adaptation: focusing on the mediating effect of perceived social support [master thesis]. Seoul: Seoul Cyber University;2014. 83.

24. Kang S, Kim S, Lee H. Predictors of PTSD symptoms in Korean Vietnam war veterans. Korean J Clin Psychol. 2014; 33(1):35–50.

25. Escolas SM, Hildebrandt EJ, Maiers AJ, Baker MT, Mason ST. The effect of attachment style on sleep in postdeployed service members. US Army Med Dep J. 2013; 35–45. http://www.cs.amedd.army.mil/amedd_journal.aspx.

26. Draijer N, Langeland W. Childhood trauma and perceived parental dysfunction in the etiology of dissociative symptoms in psychiatric inpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 1999; 156(3):379–385.

27. Heim C, Nemeroff CB. Neurobiology of early life stress: clinical studies. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2002; 7:147–159. DOI: 10.1053/scnp.2002.33127.

28. Morgan CA 3rd, Wang S, Rasmusson A, Hazlett G, Anderson G, Charney DS. Relationship among plasma cortisol, catecholamines, neuropeptide Y, and human performance during exposure to uncontrollable stress. Psychosom Med. 2001; 63:412–422. DOI: 10.1097/00006842-200105000-00010.

29. Pershing JL. Why women don't report sexual harassment: a case study of an elite military institution. Gender Issues. 2003; 21(4):3–30. DOI: 10.1007/s12147-003-0008-x.

30. Shevlin M, Boyda D, Elklit A, Murphy S. Adult attachment styles and the psychological response to infant bereavement. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2014; 5:DOI: 10.3402/ejpt.v5.23295.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download