Abstract

Purpose

The specific aims of the present study were to compare Kirogi children's mental distress and psychosocial factors between short-term (ST) and long-term groups (LT), and to identify predictors of mental distress in the two groups.

Methods

A sample of 107 Kirogi children living in the U.S. participated in this cross-sectional study and completed the following questionnaires: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children, Somatic Symptom Scale, Self-Esteem Scale, Parent-Child (P-C) Relationship Satisfaction Scale, Parent-Adolescent Communication Inventory Social, Attitudinal, Familial, and Environmental Scale, and Social Support Scale.

Results

The LT group reported higher scores on depression and anxiety, and lower scores on self-esteem and P-C relationship than the ST group. Higher scores on somatic symptoms were found in the ST group. Problematic mother-child communication and dissatisfaction with father-child relationship were significant predictors for mental distress. Self-esteem predicted depression and anxiety in the ST group; particularly self-esteem was a significant predictor for anxiety in both groups. Discrimination and process-oriented stress were significant predictors for depression and anxiety in the ST group.

"Kirogi" is a Korean word for a wild goose. Wild geese are well recognized for their commitment to family and their migration of thousands of miles every year. These characteristics depict a new type of Korean family who voluntarily and internationally separate for their children's education and social advancement[1]. Usually, a mother and her child temporarily reside in a foreign country while her husband remains in Korea to support his family financially.

The phenomenon of Kirogi families originally began with families who had to temporarily reside in foreign countries for employment or business[2]. This phenomenon became prevalent among Koreans, as English proficiency and global knowledge and perspectives became highly desirable for success in education and employment. Parents who wished their children to succeed in their lives began pursuing opportunities for their children's education in English-speaking countries[1]. The second motive for becoming Kirogi families is to avoid difficult competition for admission to prestigious universities in Korea[3]. Many students in Korea as young as 10 years old attend intensive after school programs 5~7 hours a day. In 2012, about 81% of elementary school students received private education to gain admission to prestigious universities[4]. A third unspoken reason for choosing to become a Kirogi family is a desire to escape from a conflicting marital relationship[5].

The exact number of Kirogi families is not known, but approximately 14,340 school-aged children left Korea to study in foreign countries in 2012[6]. More than 42% of them are elementary school students. More than half of the students (54%) studied in English-speaking countries, including the U.S. (28.8%), England (7.8%), Australia (7.7 %), Canada (5.0%), and New Zealand (4.7%) the rest studied in Asian countries, including China (26.5%), Japan (8.0 %), and Southeast Asian countries (11.5%)[6]. The number of Korean international students including Kirogi children ranked third among international students in the U.S. in 2012[7]. Los Angeles, New York, Chicago, Boston, and Houston were the top five U.S. metropolitan areas with large numbers of Korean students, including Kirogi children[6]. The numbers of Kirogi families are expected to continue to grow[6].

As Kirogi families pursue opportunities for their children's education and social advancement, some children experience an increased sense of independence and selfrealization[1,3,5], while others experience challenges and difficulties. In addition to stress that international students experience, such as language barriers, acculturative stress, and discrimination[8,9], Kirogi children experience stress associated with adjustment to new family living arrangements and family roles and the loss of a father figure and social support[3,5]. Particularly, Kirogi children are under great pressure to excel academically, knowing that their parents make a sacrifice for them. These stressors and challenges may lead to academic problems and mental distress[8,9,10]. Studies reported that unlike other international students and immigrant children, Kirogi children experience high levels of social stress, low self-esteem, lack of social support, and inadequate parent-child (P-C) relationships due to their unique situations. Thus, Kirogi children are at increased risks for mental distress, such as depression, anxiety, and somatic symptoms[9,11,12,13]. To date, there have been very few published studies on mental health issues and related psychosocial factors among Kirogi children. Existing studies on Kirogi families are limited to experiences of Kirogi fathers[2,5,14] or surveys of their sociodemographic characteristics[9]. Consequently, schoolteachers and health care providers, who might have immediate contact with Kirogi families, have limited knowledge about the challenges they face. Considering the rapidly increasing number of Kirogi families and the challenges and difficulties their children encounter, studies on their mental health are warranted.

We conducted the present study to assess the levels of mental distress and related psychosocial factors among Kirogi children in relation to their length of stay in the U.S. We specifically addressed these factors, because existing studies showed that the level of mental distress among international students in the U.S. depended on the length of stay[9,15,16]. The relationships between the level of mental distress among Kirogi children and the length of stay in foreign countries have not been studied yet. For the current study, we distinguished between short-term (ST) and long-term (LT) groups, referring to students who have stayed in the U.S. less or more than 24 months, respectively. Although the results are not conclusive, the first 24 months seem to be critical for overcoming language barriers and adjusting to a new culture these two challenges are closely related to mental health and academic performance[8,9,17]. Among different types of mental distress, we focused on depression, anxiety, and somatic symptoms which are the most common types of mental health problems experienced among children[9,11]. Related psychosocial factors that we chose for the present study were self-esteem, satisfaction of P-C relationship, mother-children communication, social support, and social stress.

Thus, this study aimed to assess the level of Kirogi children's mental distress and related psychosocial factors:

The target population for this cross-sectional study was Kirogi children who resided in the Midwest region of the U.S. The inclusion criteria were:(1) self-identificationas Korean,(2) between 11 and 18 years old,(3) currently living with the mother only, and (4) the father living in Korea. Based on the power analysis using G* Power 3, a sample size of at least 90 is necessary to achieve power of .95, medium effects size of .15, α of .05, and number of predictors of 16. A purposive sampling strategy, including snowball sampling, was used to identify prospective participants for this study.

This study was conducted from September 2008 to March 2009 after obtaining approval by the University of Illinois at the Chicago Office for the Protection of Research Subjects (IRB No. 2008-0575). After obtaining permission from the directors and pastors of Korean American communities, including Korean American churches and Korean American academies, the investigator distributed information about the study and posted flyers in the communities. Families who expressed interest in the study were asked to contact the primary investigator. The survey was conducted at participants' homes or other agreed-upon, convenient locations. Prior to the survey, we informed the study participants that their participation was voluntary and their responses would remain confidential. The investigator obtained written informed parental consent/permission from the mothers and assent from the children. Children completed the questionnaires in approximately 20~30 minutes. All participants received compensation for their participation (i.e., $20-value gift per family). At the end of the survey, the investigator asked mothers to recommend other Kirogi families who might be eligible to participate in the study. This snowball sampling strategy was used because Korean Americans in general have mixed perceptions of Kirogi families, which made potential participants unwilling to reveal their identity even with assurance of confidentiality.

Demographic and Kirogi family background information were obtained from the children and their mothers. Depression, anxiety, somatic symptoms, self-esteem, satisfaction with P-C relationship, mother-child communication, social support, and social stress were measured in the children (Table 1). Overall, internal consistency statistics of all measures were satisfactory in this study (α=.75~.91).

Depression was assessed using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)[18], a 20-item scale with excellent internal consistency for Korean children (α=.84)[19]. Higher scores indicate higher level of depression.

Anxiety was assessed using the state portion of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC)[20]. Subjects were asked how they felt at the time of being questioned. This scale has shown acceptable internal consistency for children (α=.77)[24] and Korean children in particular (α=.85)[21]. Higher scores indicate higher level of anxiety.

Somatic Symptom Scale was derived from the Child Health Questionnaire[22].The 11 items correspond to the most frequent signs and symptoms manifested by depressed children, such as headache, chest pain, stomach pain, or dizziness. Higher scores indicate higher level of somatic symptoms. This scale has shown excellent internal consistency (α=.78~.93)[11,13] and a high correlation with depression in diverse samples of Korean American children (Pearson's r=.61~.62)[11,13].

Self-Esteem Scale is a 7-item version of Rosenberg's scale[23,24] items include "take a positive attitude toward myself" and "satisfied with myself." Higher scores indicate higher level of self-esteem. The scale showed satisfactory internal consistency for children (α=.89)[23] and for Korean children (α=.77)[24].

Parent-Child Relationship Satisfaction Scale (PCRSS) was used to assess children's satisfaction with P-C relationship. This scale was adapted from the items of the National Longitudinal Study of Child Health[25]. Only 2 items measuring the degrees of P-C closeness and satisfaction were used for this study. The child was asked to complete two PCRSSs, one for relationship with father and another for mother. The higher the score, the more satisfied the child is with the relationship with his/her mother or father.

Parent-Adolescent Communication Inventory (PACI) [26] was used to assess openness and problems in communication with mothers. Among 20 items from the original scale, the 10-item short version was used for the present study[24]. The 4-point Likert-type scale was composed of two subscales (open communication and problematic communication). A higher score indicates that children perceive communication with their mothers as more open. This scale has shown acceptable internal consistency (α=.73~.87)[24,26].

Social Support Scale is based on Zimet's Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS)[27]. The original 12-item Zimet scale differs from existing social support scales in that it was designed to assess three specific sources of support: family, friends, and significant others. Higher MSPSS scores indicate higher perceived support. A shorter 6-item version of the scale has shown acceptable internal consistent reliabilities (α=.79~.88) for children in previous studies[27].

Social stress was measured using the Social, Attitudinal, Familial, and Environmental Scale for Children (SAFE-C)[28], a modification of the SAFE Stress Scale[3]. Both the original SAFE Stress Scale and the 36-item SAFEC have been designed to assess the multidimensional aspects of stress and have demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency (α=.79~.84) in ethnically diverse samples, including Koreans[11,28]. The scale consists of three subscales: General Social Stress, Process-Oriented Stress and Discrimination. General social stress refers to the normative sources of stress that all children face as part of their developmental process or daily lives. Processoriented stress is derived from adjusting to interaction with another culture. It is more prevalent in immigrants who are adapting to the dominant culture. Discrimination originates from "being different" and is a source of ongoing chronic stress. Higher scores indicate higher level of social stress. This scale has shown acceptable internal consistency (α=.79~.84)[11,28].

The SPSS/WIN 18.0 program was used to manage and analyze data. To compare the level of children's mental distress and related psychosocial factors between the ST group and the LT group (specific aim 1), descriptive statistics, χ2 test, t test, and multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) were used. To identify the predictors of children's mental distress in the two groups (specific aim 2), Pearson's correlation and multiple linear regressions were used.

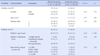

A total of 107 children in Kirogi families completed self-administered questionnaires: 55 children in the ST group and 52 children in the LT group. Their mothers (n=67) also completed demographic questionnaires. Sociodemographic characteristics of children and their mothers in the ST and LT groups are shown in Table 2. The mean age of children in the ST and LT group was 12.3±2.6 years and 14.1±2.9 years, respectively. This difference was statistically significant (t=-3.37, p =.001). The lengths of stay in the U.S. for the ST and LT group were 10.6±6.7 and 45.4±25.0 months, respectively. The mothers' average age between the two groups was also statistically different. Thus, the ages of children and mothers were controlled for in subsequent statistical analyses (MANCOVA, regressions).

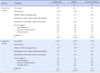

Table 3 shows the differences in level of mental distress and related psychosocial factors between the two groups using MANCOVA. Depression and anxiety of the LT group were significantly higher than those of the ST group (F=5.19, p =.007 F=9.16, p <.001, respectively). On the other hand, children in the ST group reported significantly higher levels of somatic symptoms than in the LT group (F=5.82, p=.004).

The LT group reported lower scores than the ST group in positive psychosocial factors (including selfesteem, mother-child communication, satisfaction with mother-child relationship, and satisfaction with fatherchild relationship)and higher scores in negative factors (social stress)(Table 3). Compared to children in the ST group, children in the LT group reported significantly lower level of self-esteem (F=6.07, p =.003), satisfaction with mother-child relationship (F=3.38, p =.038), and satisfaction with father-child relationship (F=11.68, p < .001).

To identify predictors for mental distress in the two groups, we conducted multiple linear regression analyses controlling for the ages of children and mothers. Overall, self-esteem, mother-child communication, satisfaction with mother-child relationship, satisfaction with father-child relationship, and social support were negatively related to all types of mental distress (depression, anxiety, and somatic symptoms)(Table 4). On the other hand, social stress (discrimination, process-oriented stress, and general social stress) was positively correlated with mental distress. Children's self-esteem was negatively correlated with all types of mental distress in both groups. In the LT group, mother-child communication was significantly negatively correlated with all types of mental distress. Particularly, anxiety had significant negative correlations with self-esteem, mother-child communication, satisfaction with mother-child relationship, satisfaction with father-child relationship, and social support (Table 4).

The results of the multiple linear regression analyses are presented in Table 5. All six models were statistically significant. For the ST group, low self-esteem and high discrimination were found to be predictors for high depression among children (R2=.47). Low self-esteem and high process-oriented stress were also found to be associated with high anxiety among children in the ST group (R2=.46). Only problematic mother-child communication was a significant predictor for high somatic symptoms among children in the ST group (R2=.15).

Among children in the LT group, problematic mother-child communication was found to be a significant positive predictor for all types of mental distress. Low self-esteem, problematic mother-child communication, and low satisfaction with father-child relationship had associations with high anxiety among children in the LT group (R2=.56). Low self-esteem significantly predicted high anxiety among children in both groups. Multicollinearity diagnostic tests showed no multicollinearities in the estimated model results (VIF: 2.29~7.48, Tolerance: .33~.85).

This study examined the level of mental distress and related psychosocial factors among Kirogi children and identified the predictors for mental distress in relation to the length of stay in the U.S.

Depression and anxiety, two of the three components of mental distress, were higher in the LT group than the ST group. In addition, self-esteem, satisfaction with mother-child relationship, and satisfaction with the fatherchild relationship were lower in the LT group. The increased level of depression and anxiety in the LT group may be explained in part by the longer separation from their fathers and longer exposure to acculturative stress, which put them at higher risk of mental distress[9]. The higher level of depression could also be due to their realization that adjusting to American education and way of living was not proceeding as they planned[3,8,9,10]. Our findings are consistent with previous studies reporting an increased risk for developing depression among international students who stayed in the U.S. for long periods of time, that is, longer than 3 years[9,15,16].

On the other hand, children in the ST group reported higher scores on somatic symptoms (third component of mental distress) than children in the LT group. Somatic symptoms are commonly associated with depression in Asian children, including Koreans, as Asian culture tends to suppress emotions and express feelings somatically[11,29,30]. Especially children in the ST group, who are less acculturated to American culture, tend to express their negative emotions somatically. Since the present study is the first to assess mental distress among Kirogi children, compatible data are not yet available in the literature.

The present study further revealed the imminent need for intervention programs for Kirogi children who are at increased risks for mental distress. Ha[10] reported that inadequate support or intervention for Kirogi families could lead to academic failures and mental health problems (e.g., substance abuse) among Kirogi children and an early return to the country of origin. In the U.S., English as a Second Language (ESL) or English Language Learners (ELL) programs are offered to international students and new immigrant students. However, the ESL and ELL programs are limited to language support, and programs for mental health issues in these populations are lacking[8,17]. Culturally relevant intervention programs designed to promoting mental health and managing early signs of mental distress, particularly for children with somatic symptoms, are needed.

Discrimination and process-oriented stress (two components of social stress) and self-esteem were significant predictors for depression and anxiety among children in the ST group. This indicates that during the first two years of stay in the U.S., social stress might be one of the contributing factors to their mental health. This finding matches previous studies reporting that international students and immigrants feel inferior and treated unfairly due to cultural differences[8,9]. With the very limited literature on Kirogi children's mental health, those groups are the most comparable to Kirogi children regarding their acculturation experiences as foreigners. Discrimination was found to be correlated with lower levels of self-esteem and higher levels of depression among immigrant adolescents[11,12,13]. It also resonates with the findings in Korean children that their self-esteem was a significant predictor for depression and anxiety[9,24,29].

On the other hand, problematic mother-child communication was a significant predictor for all types of mental distress among children in the LT group. Low satisfaction with father-child relationship also had an association with high anxiety in this group. These findings suggest that as Kirogi children stay longer in the U.S., P-C relationships begin to play a significant role in their mental health. Due to their unique family situations, Kirogi children are less likely to develop intimate P-C relationship and to rely on their parents as role models[17,29]. Inadequate P-C relationships and problematic mother-child communication may lead to family breakdown [1,30]. Due to limited contact, inadequate father-child relationship in Kirogi families is pronounced. Even if Kirogi children maintain contact with their fathers via phone, Webcam, or other media, the quality and frequency of the interactions are limited and not conducive for maintaining close relationships. Consequently, Kirogi children often feel disconnected and are less likely to be satisfied with the relationships with their fathers when they stay in the U.S. longer[3,10]. Even if mothers stay with their children to provide physical and emotional support, the present study confirmed that children in the LT group are at high risk for developing anxiety and depression. This implies that Kirogi children need more systematic support from the school, community, and society, as they spend considerable amounts of time at school[11,12].

The findings of this study need to be interpreted with caution and limitations include: first, a convenient and purposive sampling method was used; second, the study sample was limited to Kirogi families in the Midwest region of the U.S.; third, only those who were willing to overcome the mixed perception of Kirogi families in the Korean-American community participated in the study; and fourth, the potential influence of contextual factors such as family and school environments and siblings was not controlled for. All these factors limit the generalizability of the findings.

The present study revealed that developmentally and culturally relevant school-based mental health programs are needed for the increasing number of Kirogi children. Particularly, schools need to pay closer attention to Kirogi children who are vulnerable to depression and anxiety in the LT group and somatic symptoms in the ST group. In addition, low self-esteem, problematic mother-child communication, and high level of social stress were significant predictors for mental distress that warrant intervention.

Figures and Tables

Table 2

Sociodemographic Characteristics and Homogeneity between Short-term and Long-term Group (N=107)

Table 3

Differences in the Level of Mental Distress and related Psychosocial Factors between Short-term Group and Long-term Group (N=107)

References

1. Kim Y, Chang O. Issues of families that run separate household for a long time - The so-called 'Wild geese family. J Fam Relat. 2004; 9(2):1–23.

2. Choi YS. Experience of the "Geese-Fathers" family life. Theological Forurm. 2008; 54:401–437.

3. Ly P. A wrenching choice. Washington Post [Internet]. 2005. Available from: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A59355-2005Jan8.html.

4. Korea National Statistical Office. Private education expenditures survey [Internet]. 2012. Available from: http://meta.narastat.kr.

5. Um MY. Issues of male professionals living apart from their families for a long time: the so-called "Wild Geese Father". J Korean Fam Ther. 2002; 10(2):25–43.

6. Ministry of Education, Science and Technology. Education statistics [Internet]. 2012. Available from: http://www.index.go.kr/potal/main/EachDtlPageDetail.do?idx_cd=1534.

7. International of Institute Education. Open doors report on international educational exchange: top 10 sending places of origin and percentage of total international student enrollment [Internet]. 2012. Available from: http://opendoors.iienetwork.org/?p=150649.

8. Lee K, et al. The adjustments and aspirations of 'Young Korean overseas students' in U.S.A. J Soc Sci. 2005; 44:105–122.

9. Lee S. Factors related to the depression of young Korean oversea students in U. S. Korean J Adolesc Study. 2009; 16(5):99–120.

10. Ha M. 'Kirogi' Families Weigh Risks and Rewards. The Korea Times;2007. 11. 01. Available from: http://news.naver.com/main/read.nhn?mode=LSD&mid=sec&sid1=001&oid=040&aid=0000046457.

11. Choi H, Meininger JC, Robert RE. Ethnic differences in adolescent's mental distress, social stress, and resources. Adolescence. 2006; 41:263–283.

12. Yeh CJ. Age, acculturation, cultural adjustment, and mental health symptoms of Chinese, Korean, and Japanese immigrant youths. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2003; 9:34–48.

13. Choi H. Understanding child depression in ethnocultural context. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2002; 25(2):71–85.

14. Kim SS. The "Kirogi" father's change of lives and adaptation problems. J Korean Home Manag Assoc. 2006; 24(1):141–158.

15. Kim KC, Hurh WM. Beyond assimilation and pluralism: syncretic socio-cultural adaptation of Korean immigrants in the US. Ethnic and Racial Stud. 1993; 16(4):696–713.

16. Nash D. The course of sojourner adaptation: a new test of the U-curve hypothesis. Human Organization. 1991; 50:283–286.

17. Cho M. The cause of increasing young Korean students who go abroad to study. Korean J Humanities & Soc Sci. 2002; 26(4):135–152.

18. Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977; 1:385–401.

19. Park NH, Kim M. The relationship between depression and health behavior in adolescents. J Korean Acad Child Health Nurs. 2005; 11(4):436–443.

20. Spielberger CD, Edwards CD, Lushene R, Monturoi J, Platzek D. Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory for children. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologist Press;1972.

21. Cho SC, Choi JS. Development of the Korean form of the statetrait anxiety inventory for children. Seoul J Psychiatry. 1989; 14:150–157.

22. Cheng TA, Williams P. The design and development of a screening questionnaire(CHQ) for use in community studies of mental disorders in Taiwan. Psychol Med. 1986; 16:415–422.

23. Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University. Press;1965. p. 347.

24. Shin SH. Development of a structural equation model for childrens adaptation in divorced families. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2010; 40(1):127–138.

25. Carolina Population Center. Add health: The national longitudinal study of adolescent health [Internet]. 2006. Available from: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth.

26. Barnes HL, Olson DH. Parent-adolescent communication scale. In : In Olson DH, McCubbin HI, Barnes H, Larsen A, Muxen M, Wilson M, editors. Family Inventories. St. Paul, MN: Family Social Science, University of Minnesota;1982. p. 33–48.

27. Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988; 52:30–41.

28. Chavez DV, Moran VR, Reid SL, Lopez M. Acculturative stress in children: a modification of the SAFE scale. Hisp J Behav Sci. 1997; 19:34–44.

29. Kim SH, Kim CK. Depression in adolescence: path analysis of the effects of socio-environmental variables and cognitive variables. Korean J Child Stud. 2006; 27(6):249–261.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download