Abstract

Purpose

In this study relationships of different types of domestic violence experiences and parental alcoholism in childhood with adult mental and family health were explored. Adult mental health outcomes included resilience, sense of belonging, life satisfaction, and depression.

Methods

Data for this secondary analysis were from a cross-sectional study employing a web-based survey of 206 Koreans, including 30 adult children of alcoholics (ACOAs). A two-step cluster analysis was performed with seven domestic violence experience items as determinants of cluster membership.

Results

In the ACOA cohort, four clusters were identified by childhood domestic violence experience-Low Violence, Witness, Emotional Violence, and Multiple Violence. Only two clusters were found among non-ACOAs-None versus Multiple Violence. All adult mental health and family health characteristics were significantly different between these six empirically-derived clusters. The ACOAs in the Emotional Violence group showed the lowest resilience and sense of belonging, and highest depression scores, which were significantly different from each corresponding score of the ACOAs in the Witness group. ACOAs who experienced multiple violence showed lowest level of family health among the six clusters.

Childhood exposure to domestic violence is a key risk factor for developing life-long deleterious outcomes (Kulkarni, Graham-Bermann, Rauch, & Seng, 2010). Domestic violence can involve physical, sexual, as well as emotional, verbal abuse and witnessing violence. Unfortunately, exposure to domestic violence in childhood is not rare. A 2008 U.S. national survey (National Survey of Children's Exposure to Violence) identified that the prevalence rate of any child maltreatment was as high as 11.1% and witnessing family violence was as high as 5.1% (Turner, Finkelhor, & Ormrod, 2010). In the East Asia and Pacific region also, a similar but growing number of children appear to experience more than one type of domestic violence with almost halt experiencing five or more types (Fry, McCoy, & Swales, 2012).

Exposure to domestic violence can often result in severe and multiple consequences, and they are mostly life-long and complex psychological symptom profiles including depression, anxiety disorders, substance abuse, suicidal attempts, and violence towards others (Agaibi & Wilson, 2005; Runyan et al., 2002). In particular, relational abuse, such as emotional and verbal abuse, has been identified to play a critical role in developing shameproneness and depressive symptoms (Kim & Yoo, 2000; Kulkarni et al., 2010). Critical gaps remain, however, in the understanding of the complex interrelationships between the types of domestic violence experiences in childhood and the psychological consequences in adulthood. Most studies have focused on separate and relatively narrow categories of domestic violence (e.g., sexual or physical abuse), paying less attention to effects of different types of experiences on outcomes in adulthood.

Individuals who grew up in alcoholic households are also more likely to have childhood adverse experiences. Parents' alcohol problems appear to be significantly associated with children's peer bullying and victimization (Eiden et al., 2010). As the number of childhood adverse events increases, the risk of alcoholism and depression in those who grew up in alcoholic families increases (Anda et al., 2002). As reported in our previous studies, however, the negative consequences related to parents' alcohol problems and the number of adverse experiences in ACOAs' childhood have also been found to decrease as resilience and/or sense of belonging increase (Lee & Cranford, 2008; Lee & Williams, 2013). Specifically, resilient ACOAs are more likely to have tolerance of negative effect by developing better problem-solving or coping skills or positive acceptance of change (Lee & Williams, 2013). In addition, feeling valued and connected within a social system can help the individual to recognize more positive aspects in their lives and reduce potential deleterious effects of any sustained stress (Hagerty & Patusky, 1995; Lee & Williams, 2013). Having a cohesive family with supportive relationship and greater satisfaction with life are another protective factors from negative outcomes, in particular for depression (Kim et al., 2010; Lease, 2002).

However, little is known about whether ACOAs would have experienced more distinctive types of domestic violence in their childhood and how those potentially different types of domestic violence in childhood would influence mental health in adulthood. This study therefore aimed to analyze the relationships of different types of childhood domestic violence in relation to parents' alcohol problems with the adult mental health, including resilience, sense of belonging, life satisfaction, and depression, as well as family health, including family functioning and social support. A profile analysis approach (i.e., cluster analysis) was used in this study to provide a unique contribution that identifies different patterns of childhood experiences of domestic violence. We believe that this study can contribute to a better understanding of psychological features and mechanisms in adulthood in relation to childhood adversity, including parental alcoholism and domestic violence.

The parent study with cross-sectional design explored relationships and built a path model between parental alcoholism, sense of belonging, resilience, and depression (Lee & Williams, 2013). Data were collected from 206 Koreans living in the Midwestern United States, using a web-based survey. Approval was granted by the institutional review board of one university where voluntary participants were recruited. Details about the web-based survey procedure were described previously. In this paper, secondary analyses were performed with the data from the 206 participants' responses, focusing on their childhood domestic violence experiences along with adult mental health and family health variables.

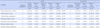

Voluntary community participants were invited to participate in a web-based survey about social experiences of Koreans in the U.S. via both on- and off-line flyers. The sample consisted of self-identified Korean males or females who were identified as eligible, if they were at least 18 years old and could read and understand either English or Korean. Among the 206 respondents who completed the web survey, more than half were female (59.8%) with a mean age of 28.4 years (SD=6.9). The biggest subset of the sample (54%) was graduate students, and almost half (46.5%) were employed in either full-time or part-time positions. A majority (68.0%) had lived in the United States for five years or less. As shown in Table 1, 30 (14.9%) respondents from the entire sample were identified as ACOAs who grew up with an alcoholic parent, based on their overall score of 3 or above on the short version of the Children of Alcoholics Screening Test (CAST-6)(Hodgins, Maticka-Tyndale, el-Guebaly, & West, 1993) which consists of 6 items about adult children's feelings, attitudes, perceptions, and experiences as they relate to their parents' alcohol problems.

Childhood domestic violence experiences were retrospectively measured by a total of nine items, with a choice to answer "yes" or "no," regarding witnessing any types of domestic violence, being either a victim or a perpetrator of physical, emotional, verbal, or sexual violence in childhood. The participants were also asked about how satisfied they are with their current life on a 5-point Likert-type response format (1=very dissatisfied; 5=very satisfied). Demographic characteristics were asked regarding the participants' age, gender, marital status, religion, country of birth (i.e., Korea or USA), and length of stay in the U.S.

Five additional measures provided the data for the secondary analysis in this study. The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC)(Connor & Davidson, 2003), which is a 25-item self-report scale with a 5-point Likert-type response format (0=rarely true; 4=true nearly all the time), assessed the participants' resilience from various aspects including personal competence, positive affect and acceptance against stress, control, and spiritual influence. The possible overall score ranges from 0 to 100 with a higher score indicating better resilience. Cronbach's α in this study was .92.

Sense of belonging, known for its significant association with depression (Choenarom, Williams, & Hagerty, 2005; Turner & McLaren, 2011),was measured by the Sense of Belonging Instrument-Psychological (SOBI-P) (Hagerty & Patusky, 1995). The SOBI-P is an 18-item self-report measure assessing an individual's experience of feeling valued and the perception of fit or connectedness within a system or environment. Respondents were asked to reflect on the past month, and to give ratings on a 4-point Likert-type scale (1=strongly disagree; 4=strongly agree), with higher scores indicating a greater sense of belonging. Cronbach's α with the study sample was .93.

Participants' depression was measured by the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II)(Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) which assesses the severity of depression by having respondents' report on several major symptoms. The BDI-II is a 21-item self-report inventory that asks respondents about their feelings over the past two weeks. Each item is scored from 0 (symptom is not present) to 3 (symptom is severe), with higher overall scores indicating more depressive symptoms. Cronbach's α in this study was .90.

Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ-6)(Sarason, Sarason, Shearin, & Pierce, 1987) was used to measure rather familial and environmental social support compared to individual feelings of sense of belonging. The SSQ-6 consists of 6 items to identify persons in the respondent's environment that can help in specific situations. The respondents were also asked to evaluate, on a 6-point scale, their level of satisfaction with the support they perceived (1=very unsatisfied; 6=very satisfied). Cronbach's α in this study was .93.

The Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scale-III (FACES-III)(Olson, Portner, & Lavee, 1985) was employed to measure functioning of the family where both respondents and their parents belong. FACES-III consists of two subscales-family adaptability and family cohesion, each with 10 items (1=almost never; 5=almost always). The possible overall score ranges from 20 to 100. The higher the total score, the better family adaptability and cohesion the participant's family has. In this study, Cronbach's α for family cohesion was 0.86; for family adaptability .79.

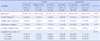

All statistical analyses were accomplished using IBM© SPSS version 19. The threshold for significance was set at p<.05. Descriptive statistics were computed to compare domestic violence experiences and psychological characteristics between ACOAs and non-ACOAs. The main analysis of data in this study was two-fold. Firstly, with seven domestic violence items as determinants of cluster membership (Table 2), a two-step cluster analysis was performed using a log-likelihood distance measure and Schwarz's Bayesian Clustering Criterion (BIC). The cluster analysis was run for ACOAs and non-ACOAs separately, with no number of clusters specified a priori. Average silhouette coefficient was used as a measure of cluster validity and strength of clustering results, because it measures combining cohesion and separation for individual points as well as clustering (Kaufman & Rousseeuw, 1990). Secondly, significant differences in psychological variables between the clusters were determined using nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test, due to unequal sizes across the new clusters.

As shown in Table 1, there were significant differences in childhood experience of domestic violence between ACOAs and non-ACOAs, with the ACOA group participants experiencing more domestic violence by 3 to 10 times depending on the type of experience (p<.05), except for sexual violence. In particular, being a victim of verbal or emotional violence, being a perpetrator of emotional violence, and witnessing any domestic violence were very distinctive types found in ACOAs (p<.01). Since there were only two subjects who experienced sexual violence as a victim and/or a perpetrator, sexual violence items were not used in the next cluster analysis.

For the psychological features, ACOAs had significantly lower levels of sense of belonging and social support, and higher levels of depression than the non-ACOA group (p<.05). No statistically significant mean differences were found in resilience and life satisfaction as well as family functioning, both overall score and the two subscale scores-family cohesion and family adaptability.

The seven types of domestic violence items, except sexual violence ones, were subjected to a cluster analysis that investigates the specific sub-groups to each cohort by their different domestic violence experiences. Table 2 presents a very distinctive pattern of clusters for ACOAs compared to non-ACOAs, along with the proportion of different types of domestic violence for each cluster. Average silhouette coefficients were 0.6 for ACOAs, indicating a reasonable structure, and 0.8 for non-ACOAs, indicating a strong structure (Kaufman & Rousseeuw, 1990).

In the analysis with 30 ACOAs, four clusters were identified with 10 participants in the first cluster (Cluster 1), 8 participants in the second cluster (Cluster 2), 7 participants in the third cluster (Cluster 3), and 5 participants in the fourth cluster (Cluster 4). Cluster 1 appears to be less exposed to any domestic violence, thus labeled "Low Violence" group. Cluster 2 involves witnessing any kinds of domestic violence and partially being victim of verbal violence, which is labeled "Witness." Cluster 3 appears to be mainly victims of emotional violence, so it is labeled "Emotional Violence." Cluster 4 is labeled "Multiple Violence" as it involves almost all types of domestic violence experiences. Only two clusters were found among 171 non-ACOAs, with 131 participants in the first "No Violence" cluster, and 40 participants in the second "Multiple Violence"cluster. These six new clusters by childhood violence experiences were used together in the following analyses to examine demographic and adult psychological characteristics in the sample.

There were no statistical differences found in demographic variables, including age, gender, marital status, religion, and country of birth with length of stay in the U.S. between the six clusters (Table 3). However, psychological features at both individual and familial levels were significantly different between the six clusters by childhood violence experiences.

Kruskal-Wallis tests were conducted to evaluate differences among the six clusters in adult mental health and family health variables (Figure 1). The test, which was corrected for tied ranks, was significant for resilience, sense of belonging, depression, social support and family functioning in the overall as well as the two sub-scales (p<.05). No significant difference was found in life satisfaction. Follow-up post hoc tests were conducted to evaluate pairwise differences among the six clusters for each significant test, controlling for Type 1 error across tests by using the Bonferroni approach. The pair with a significant difference was indicated with an asterisk in each box plot in Figure 1.

One of the ACOA clusters, the Emotional Violence group, had significantly lower levels of resilience (Figure 1-a) and sense of belonging (Figure 1-b), and higher levels of depression (Figure 1-d), than ACOAs in the Witness group as well as non-ACOA with no violence experiences (p<.05). Interestingly, ACOAs in the Witness group reported greater resilience than ACOAs in the Low Violence group (p<.05). Between the two non-ACOA groups, as expected, the No Violence experienced group had greater sense of belonging (Figure 1-b) and lower depression scores than the Multiple Violence group (Figure 1-d)(p<.05). For the familial health variables, ACOAs in the Multiple Violence group had the lowest levels of social support (Figure 1-e) and family functioning overall (Figure 1-f) as well as the two subscale scores (Figures 1-g and 1-h)(p<.05).

Studies have reported that childhood experience of domestic violence plays a substantial role in developing deleterious outcomes, even in later life. This study has further expanded those findings, by identifying and comparing specific patterns of domestic violence experiences in childhood between ACOAs and non-ACOAs via a cluster analysis and exploring their relationships with adult mental health as well as family health.

Before the new clusters were identified by domestic violence experiences in childhood, only significant differences between ACOAs and non-ACOAs were in sense of belonging, social support, and depression (Table 1). The unique clusters of ACOAs by their childhood domestic violence experiences, however, identified more variations in those adult mental health as well as family health variables. In particular, ACOAs who were victimized by emotional violence in the family reported the highest depression score as well as the lowest levels of resilience and sense of belonging among the six clusters (p<.05), which include multiple violence-experienced, both ACOAs and non-ACOAs. In addition, the post hoc test revealed that ACOAs who witnessed domestic violence reported much greater resilience, sense of belonging, and lower depression scores compared to the emotional abused ACOAs (p<.05). Statistically not significant, but as Figures 1-a, 1-b, and 1-d illustrate, the multiple violence-experienced ACOAs also appeared better than the emotionally victimized ACOAs in terms of resilience, sense of belonging, and depression.

Among various types of violence, emotional abuse is one of the most common types in alcoholic families (Verduyn & Calam, 1999). In our study, the cluster size of emotional violence group was not much different from the other clusters' in ACOAs, but its associations to adult mental health (i.e., depression, resilience and sense of belonging) were significant. More severe levels of depression in the emotionally abused victims have also been found in other studies. Compared to other types of violence, emotional abuse in the family showed a stronger association with depression as well as other emotional difficulties, including aggression, instability, or dependency (Nicholas & Rasmussen, 2006; Verduyn & Calam, 1999). Because domestic violence is passed from one generation to the next, it has been thought that domestic violence affects not only the victim but also the psychological states of the witnesses and especially the psychosocial development of children. However, in the current study findings indicate that ACOAs who witnessed domestic violence experienced better mental health than the emotionally victimized group, possibly due to the fact that emotional violence can be a more direct victimization that involves more intense feelings than just witnessing (Kulkarni et al., 2010).

The significant differences between the emotionally victimized and the multiple violence-experienced ACOAs remained at the familial level as well, but in the opposite direction. The Multiple Violence-experienced ACOA group showed the lowest overall and subscale scores of family functioning as well as social support (p<.05), which is not surprising. Experiencing multiple incidents of domestic violence, including physical and emotional ones, can be more likely to create constant fear for every family member and to make it difficult for family members to build a cohesive, adaptable, and supportive family environment. Traumatic childhood experiences are also more likely to correspond to reduced opportunities to build attachment within the family (i.e., having insecure attachments) or reduced feelings of trust within interpersonal relationships (Agaibi & Wilson, 2005).

Interestingly though, except for the Multiple Violence-experienced cluster, most of the ACOA participating in this study seem to have a similar level of family functioning to that of non-ACOAs with no violence experiences. However, these associations at the familial level should be interpreted carefully. It may be difficult to make a direct relationship between family functioning and psychological outcomes in the context of domestic violence. When considering what family cohesion and family adaptability refers to, however, we can make a possible interpretation of the double-sidedness of both family cohesion and adaptability in the alcoholic families. Family cohesion means the emotional intimacy in a family, and family adaptability means the changeable range of a family system (Olson et al., 1985). The closed system of alcoholic families (Lease, 2002; Lee & Williams, 2013) is high likely to hinder potential, healthy support from outside the family, but because the family as a whole has been through the very same adversities, unless their domestic violence experience becomes fatal (i.e., multiple types of violence occurring), they could develop intimate relationships within the family that they could lean on as well as more flexible coping strategies than the other families would do. Family focused-intervention, thus, can bring the greatest potential for success with alcoholic families by producing significant improvements, for instance, in positive parenting styles and child behaviors. Nonetheless, further studies are required to decipher the details behind such a relationship between certain types of domestic violence and family functioning in alcoholic families.

Nevertheless, childhood exposure to domestic violence, in general., increases the risk of experiencing negative mental health consequences, physical health sequelae, and high-risk sexual behaviors (Fry et al., 2012). Particularly, depression and anger have been found to be more prevalent in ACOAs who lived through traumatic experiences such as emotional, physical, and sexual abuse during childhood. In addition, those who have been the victim of violence during their childhood will use violence to a greater extent as adults, such as intimate partner violence. Therefore, family violence offenders should be included in any clinical approach to intervene in family violence, and their past experience and psychological consequences need to be carefully assessed and addressed. Practical barriers though exist that impede the identification of individuals early on the initial risk. Children may be mostly perceived as "belonging to" and "in debt toward" their parents and caretakers. In addition, victims of violence are discouraged from speaking out and obtaining external support and discussing or reporting violence publicly, thus often remain invisible (Runyan et al., 2002).

This study has limitations. The data were from a web-based survey that only certain participants could access, so the results may not be generalizable. In addition, the measure of violence did not specify the exact nature, frequency, or severity of the violence experiences. All violence experienced was assessed retrospectively and current adulthood experience was not includeed. Lastly, given the relatively small proportion of ACOAs in the current study (~15%), no further multivariate analyses could be conducted to explore causal., underlying relationships among the variables.

However, there also are important strengths. We were able to identify unique patterns of childhood domestic violence experiences in ACOAs that are significantly associated with adult psychological features and family health. Thus, the data fill gaps in our understanding of how domestic violence and parental alcoholism in childhood influence later mental health, with addressing differences by the type of domestic violence.

This study identified unique patterns of childhood experience of domestic violence among ACOAs and compared them to those in non-ACOAs. Those who were victims of emotional violence showed negative psychological features at the individual level and those exposed to multiple incidents of domestic violence were shown to have lower levels of family functioning than others. The findings suggest that ACOAs and non-ACOAs may have experienced very different patterns of childhood domestic violence which are associated with distinct psychological entities in their adulthood. On the basis of these results, comprehensive clinical approach to alcoholic families is encouraged to prevent negative health outcomes, by assessing and identifying the different types of domestic violence experiences and family functioning.

The author reports no conflicts of interest. The author alone is responsible for the content and writing of the article.

This research and manuscript were prepared by Hyunhwa Lee in her personal capacity. The opinions and assertions in this manuscript are the author's own and do not necessarily represent those of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the United States government.

This project was supported in part by grants from the Rackham Graduate School (Dissertation Fellowship) and the School of Nursing (New Investigator Award), University of Michigan.

The author thanks Joan Austin, Consulting Services for NINR, and Cindy Clark, NIH Library Writing Center, for manuscript editing assistance.

Figures and Tables

| Figure 1Differences in Adult Mental Health and Family Health between Empirically-Derived Clusters by Childhood Domestic Violence Experiences (a, b, c).

Differences in Adult Mental Health and Family Health between Empirically-Derived Clusters by Childhood Domestic Violence Experiences (d, e, f).

Differences in Adult Mental Health and Family Health between Empirically-Derived Clusters by Childhood Domestic Violence Experiences (g, h).

|

Table 1

Differences in the Types of Childhood Domestic Violence Experience and Adult Psychological Features, and Family Health between ACOAs and Non-ACOAs

References

1. Agaibi CE, Wilson JP. Trauma, PTSD, and resilience: A review of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2005; 6:195–216.

2. Anda RF, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, Chapman D, Edwards VJ, Dube SR, et al. Adverse childhood experiences, alcoholic parents, and later risks of alcoholism and depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2002; 53:1001–1009.

3. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory: Manual. 2nd ed. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corp;1996.

4. Choenarom C, Williams RA, Hagerty BM. The role of sense of belonging and social support on stress and depression in individuals with depression. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2005; 19:18–29.

5. Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003; 18:76–82.

6. Eiden RD, Ostrov JM, Colder CR, Leonard KE, Edwards EP, Orrange-Torchia T. Parent alcohol problems and peer bullying and victimization: Child gender and toddler attachment security as moderators. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2010; 39:341–350.

7. Fry D, McCoy A, Swales D. The consequences of maltreatment on children's lives: Asystematic review of data from the East Asia and Pacific Region. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2012; 13:209–233.

9. Hodgins DC, Maticka-Tyndale E, el-Guebaly N, West M. The CAST-6: Development of a short-form of the Children of Alcoholics Screening Test. Addict Behav. 1993; 18:337–345.

10. Kaufman L, Rousseeuw PJ. Finding groups in data: An introduction to cluster analysis. New York: John Wiley & Sons;1990.

11. Kim S, Nam KA, Lee H, Hyun MS, Lee H, Kim HL. Factors predicting depressive symptoms in employed women: Comparison between single and married employed women in Korea. J Korean Acad Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2010; 19:339–347.

12. Kim YH, Yoo SJ. The study of child abuse and health status. J Korean Acad Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2000; 9:651–669.

13. Kulkarni MR, Graham-Bermann S, Rauch SAM, Seng J. Witnessing versus experiencing direct violence in childhood as correlates of adulthood PTSD. J Interpers Violence. 2011; 1264–1281. (OnlineFirst published).

14. Lease SH. A model of depression in adult children of alcoholics and nonalcoholics. J Couns Dev. 2002; 80:441–451.

15. Lee HH, Cranford JA. Does resilience moderate the associations between parental problem drinking and adolescents' internalizing and externalizing behaviors?: A study of Korean adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008; 96:213–221.

16. Lee H, Williams RA. Effects of parental alcoholism, sense of belonging, and resilience on depressive symptoms: A path model. Subst Use Misuse. 2013; 48:265–273.

17. Nicholas KB, Rasmussen EH. Childhood abusive and supportive experiences, inter-parental violence, and parental alcohol use: Prediction of young adult depressive symptoms and aggression. J Fam Violence. 2006; 21:43–61.

18. Olson DH, Portner J, Lavee Y. FACES III. St. Paul, MN: Family Social Science, University of Minnesota;1985.

19. Runyan D, Wattam C, Ikeda R, Hassan F, Ramiro L. Chapter 3: Child abuse and neglect by parents and other caregivers. In : Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R, editors. World report on violence and health. Geneva: World Health Organization;2002.

20. Sarason IG, Sarason BR, Shearin EN, Pierce GR. A brief measure of social support: Practical and theoretical implications. J Soc Pers Relat. 1987; 4:497–510.

21. Turner HA, Finkelhor D, Ormrod R. Poly-victimization in a national sample of children and youth. Am J Prev Med. 2010; 38:323–330.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download