Abstract

Objectives

The purpose of this in vivo study was to investigate the microbial diversity in symptomatic and asymptomatic canals with primary endodontic infections by using GS FLX Titanium pyrosequencing.

Materials and Methods

Sequencing was performed on 6 teeth (symptomatic, n = 3; asymptomatic, n = 3) with primary endodontic infections. Amplicons from hypervariable region of the small-subunit ribosomal RNA gene were generated by polymerized chain reaction (PCR), and sequenced by means of the GS FLX Titanium pyrosequencing.

Results

On average, 10,639 and 45,455 16S rRNA sequences for asymptomatic and symptomatic teeth were obtained, respectively. Based on Ribosomal Database Project Classifier analysis, pyrosequencing identified the 141 bacterial genera in 13 phyla. The vast majority of sequences belonged to one of the seven phyla: Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Fusobacteria, Proteobacteria, Spirochetes, and Synergistetes. In genus level, Pyramidobacter, Streptococcus, and Leptotrichia constituted about 50% of microbial profile in asymptomatic teeth, whereas Neisseria, Propionibacterium, and Tessaracoccus were frequently found in symptomatic teeth (69%). Grouping the sequences in operational taxonomic units (3%) yielded 450 and 1,997 species level phylotypes in asymptomatic and symptomatic teeth, respectively. The total bacteria counts were significantly higher in symptomatic teeth than that of asymptomatic teeth (p < 0.05).

Microbial infection of root canal system is essential cause of apical periodontitis.1 To understand the pathogenic process of endodontic infection and thus develop more effective strategies for intracanal disinfection, clinicians should have the information about the microbial profile or diversity in endodontic infection.2-4 Although various molecular diagnostic techniques have been developed, bacterial diversity in endodontic infections has not been sufficiently performed. Previous studies by 16S rRNA gene clone libraries demonstrated that 391 bacterial taxa belong to 82 genera and 9 phyla have been identified in primary endodontic infections.5-10 However, interpretation of the relative abundance of different taxa identified by any molecular method must be done with care.11 The steps of DNA extraction, PCR amplification (choice of primers), and intrinsic differences in 16S rDNA copy number may result in a skewed taxonomic interpretation of the microbial profiles, and probably result in an underestimation of microbial diversity.12 Furthermore, 16S rRNA gene-based clonal analysis utilizes the conventional Sanger capillary sequencing technique, which has a limitation to detect the low-abundance taxa.13 The pyrosequencing technique, however, is a new approach that allows for extensive sequencing microbial populations without clonal bias of amplified 16S rRNA sequences.14 Recently, pyrosequencing studies in the human oral cavity and endodontic infection revealed higher bacterial diversity than previously reported.11,15 However, the pyrosequencing systems used in both studies had the short length of sequences (< 250 bases) for bacterial detection and therefore, is unsuitable for robust reconstruction of bacterial communities especially for lower taxa levels such as the species level. Therefore, the present study was to investigate the microbial profile in asymptomatic and symptomatic teeth with primary endodontic infections by the current generation GS FLX Titanium pyrosequencing, which has long sequence length more than 400 bases.

Six patients (4 men and 2 women) aged 25 to 62 years were included in this study. Specimens from six patients were obtained from a maxillary anterior tooth, a mandibular anterior tooth, a mandibular premolar, a maxillary premolar and two mandibular molars. All teeth had a primary endodontic lesion, but did not have active periodontal diseases. Three individuals had lesions that were deemed symptomatic (PY), whereas the rest three individuals were asymptomatic (PN). Symptomatic group included percussion pain, spontaneous pain, fistulous track formation, and swelling. Patients who were receiving antiviral, antibiotics, or immunosuppressive therapy were excluded from the study. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Seoul National University Dental Hospital, Seoul, Korea. Written informed consent was obtained after the procedures had been fully explained.

Intracanal exudate specimens were collected at the time of scheduled nonsurgical endodontic treatment. Nonsurgical endodontic treatment was performed in teeth with primary lesion. The tooth under treatment was polished with pumice and isolated with rubber dam. Blockout resin (Ultradent, South Jordan, UT, USA) was applied around the dam margin to prevent leakage of saliva. The surfaces of the tooth, rubber dam, clamp, and blockout resin were decontaminated by scrubbing with 30% (v/v) hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (Sigma-Aldrich Company Limited, Poole, UK), and iodine tincture (10% w/v) (Betadine, Seton Healthcare Group plc, Oldham, UK) and NaOCl (2.5%) (Sainsbury's household bleach, J. Sainsburyplc, London, UK) were then applied for 1 minute. The solutions were inactivated by sterile sodium thiosulphate solution (5% w/v) (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA). Access cavity preparation using a sterile tungsten carbide bur in an air-turbine handpiece was done. The bacterial samples were taken by ten sterile paper points for each canal following access cavity preparation. Genomic DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA mini Kit (Invitrogen Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

The following universal 16S rRNA primers were used for the PCR reactions, 27F (GAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG) and 518R (WTTACCGCGGCTGCTGG).16 Each PCR reaction was carried out with two of the 25-µL reaction mixtures containing 60 ng of DNA, 10 µM of each primer (Macrogen, Seoul, Korea), and AccuPrime Taq DNA Polymerase High Fidelity (Invitrogen, WI, USA) in order to obtain the following final concentrations: 1.25 U of Taq polymerase, 50 mM of MgSO4, and 10X of the PCR buffer. A C1000 thermal cycler (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA, USA) was used for the PCR as follows: (i) an initial denaturation step at 94℃ for 3 minutes, (ii) 30 cycles of annealing and extending (each cycle occurred at 94℃ for 60 seconds followed by 54℃ for 30 seconds and an extension step at 72℃ for 60 seconds), and (iii) the final extension at 72℃ for 5 minutes. After this PCR amplification, the amplicons were purified by gel electrophoresis and two-time purifications using a QIA quick Gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and QIA quick PCR purification kit. In order to recover a sufficient amount of purified amplicon from the purification steps, two 25-µL reaction mixtures were combined into one mixture prior to amplicon purification. All amplicons were pooled and Amplicon pyrosequencing was performed by Macrogen Inc. (Seoul, Korea) using a 454/Roche GS-FLX Titanium instrument (Roche, Nutley, NJ, USA).

Analysis of sequencing data was conducted using pyrosequencing pipeline at Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) 10 (http://pyro.cme.msu.edu/index.jsp). Low-quality sequences were trimmed using pyro initial process to remove sequences having a length shorter than 300 nucleotides and no ambiguous nucleotide with an average quality score of less than 20.15,17 Pyrosequencing reads were aligned using Infernal and clustered at 97% sequence similarity using the complete linkage clustering. In addition, representative reads were extracted from clusters using dereplicates in RDP software. The RDP Classifier was used to assign representative operation taxonomic unit (OTU) reads to taxonomical hierarchy with a confidence threshold of 50% at all phylum, class, order, family and genus level. To get information of strain level, the identification of phylogenetic neighbor was carried out by the BLAST against the EzTaxon database of type strain of recognized prokaryotic names.18

The six samples yielded 56,094 16S rRNA sequence reads with an average length of 440 bases (10,639 reads for PN group and 45,455 reads for PY group) following the sequence quality filtering steps (Table 1). In total, 8.42% and 3.25% of the sequences could not be assigned to phylum or genes levels, respectively, and were classified at the next higher resolution level of family, order, or class. Most of the sequences that were discarded had insufficient length rather than poor sequence qualities. In total, 13 bacterial phyla 21 classes and 142 genera were assigned by RDP II Classifier to pyrosequences.

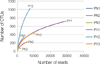

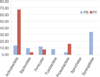

The richness of total bacterial communities of asymptomatic and symptomatic teeth with primary apical periodontitis at 3% difference was estimated by rarefaction analysis. The shape of the curves indicates that bacterial richness of the sampled infected root canals is not yet complete, especially in symptomatic group (Figure 1). The individual sequences could be clustered into unique V3 tag sequences, representing 13 known phyla. The vast majority of sequences belonged to one of the seven phyla in the order of Actinobacteria, Synergistetes, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Fusobacteria, and Spirochetes. Each of other 6 phyla (Acidobacter, Planctomycete, TM7, Nitrospira, Cyanobacter, and Chloroflexi) corresponded to less than 1% of the sequences. Of the major phyla, Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria were overrepresented in symptomatic teeth, whereas Bacteroides, Firmicutes, Fusobacteria, Spirochetes, and Synergistetes were more abundant in asymptomatic teeth (Figure 2). Planctomycete and Nitrospira were newly found in primary endodontic infections.

At genus level, both symptomatic and asymptomatic teeth contained total 142 different genera. Three genera (Pyramidobacter, Streptococcus, Leptotrichia) constituted about 50% of microbial profile in asymptomatic teeth, whereas Neisseria, Propionibacterium and Tessaracoccus were found in symptomatic teeth (69%). The 10 most abundant genera in asymptomatic teeth and the 10 most prevalent genera in symptomatic teeth were summarized (Figure 3). Most of the genera were of relatively low abundance. At species level, defined as OTU at 3% difference, about 450 and 1997 phylotypes were found in asymptomatic and symptomatic teeth, respectively (Table 1). The most diverse species in the asymptomatic teeth was the Pyramidobacter piscolens, whereas Propionibacterium acidifaciens was in symptomatic teeth (Table 2).

The introduction of high-throughput, deep-coverage pyrosequencing has dramatically increased the resolution at which microbial profile can be analyzed.11 The present GS FLX Titanium pyrosequencing results clearly demonstrated higher microbial diversity than previously reported by using 16S rRNA gene-based clonal analysis in endodontic infection with different clinical conditions.19,20 16S rRNA gene-based clonal analysis utilizes the Sanger capillary sequencing technique, which has a limitation in depth of coverage.13 As a result, the less abundant microflora cannot be selected for sequencing. In a previous study, only 8 phyla and 25 genera were detected in seven root canal samples by using the Sanger sequencing.15 On the contrary, the present pyrosequencing study identified 13 bacterial phyla and 142 genera. This might due to the difference of depth of coverage for detection of low-abundance taxa between two techniques.

In the dental field, the previous pyrosequencing studies used GS 20 system and GS FLX platform.11,15 However, those systems fundamentally use short reading length of sequence (100 to 250 bases) and thus cannot produce full length 16S rRNA sequences, traditionally used for microbial taxonomic studies.19 On the contrary, the current GS FLX Titanium pyrosequencing generated informative sequences longer (more than 400 bases) than those two systems, therefore enabling more accurate taxonomic assignments to be made. In other words, since we only included the sequence reads longer than 400 bp in the final dataset, all analyzed sequences contained at least two of the V1, V2, and V3 regions, which are important neucleotide regions for detection of similarity between new bacteria and bacteria listed on the DSMZ Bacterial Nomenclature Web site (http://www.dsmz.de/microorganisms/bacterial_nomenclature.php).

A recent study using the current GS FLX Titanium pyrosequencing in ten teeth with chronic apical periodontitis demonstrated 10 phyla, 84 genera, and 187 species-level phylotypes confined to apical third root segment,21 which showed relatively lower abundance of bacterial diversity than our results. This might be due to the difference of sample collecting sites in the root canal between two studies. Our study used the samples taken from the entire extent of the canal by using 7 paper points, whereas the other study confined in the apical canal area.

One of the strong points of this study is the resolution and the deep coverage of sequence identification with the help of pyrosequencing in primary infected root canals. Due to the insufficient and inaccurate classification on "uncultured bacteria", the vast majority of unnamed oral taxa have been referenced by clone numbers or 16S rRNA GenBank accession numbers, or identified at most down to the genera level.22-24 In this study, the hierarchical taxonomic structure of the EzTaxon-e database allowed us the complete identification of obtained root canal massive data at the species level for the first time.

The most predominant bacterial phylum detected in the present study was Actinobacter, whereas Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria were in the previous pyrosequencing studies by Li et al. and Siqueira Jr et al., respectively.15,21 This might be due to the racial and geographic difference. Another remarkable discovery in this study was the presence of Planctomycete and Nitrospira, which are known bacterial phyla in marine, in primary endodontic infection because they have never been reported previously in the root canal microbial ecosystem.25 This could be explained by the specific diet for Koreans. Koreans consume a volume of salted foods like Kimchi, raw fish, and Jotgal which may be good sources for Planctomycete and Nitrospira. As previously reported by Singnoretto et al. consumption of specific foods could affect the microbiological composition of saliva and dental plaque of subjects.26 Nonetheless, the present data obtained in primary endodontic infections showed a less diverse microflora than the bacterial diversity in saliva and supragingival plaque through pyrosequencing, confirming that endodontic microflora are a subset derived from the total oral microflora.11,15

One important factor in the variation of endodontic microflora is the presence or absence of clinical signs and symptoms.2 The microbial community within the root canal is thought to undergo ecological succession as nutritional, acidic, and oxygenation changes occur in conjunction with bacterial growth.27 This chronic infectious process can progress asymptomatically, but dramatic clinical symptoms can occur.20 Although the present study did not show any correlation between clinical symptoms and specific bacteria because of small sample size, symptomatic teeth had nearly 4 times more bacterial diversity than the asymptomatic teeth at the species level. This result suggests that lack of clinical symptoms related to low bacterial growth in the root canal and periapical region.4 Therefore, it is possible that more virulent multispecies communities can form as a result of overall bacterial combinations and give rise to clinical symptoms and signs.28 In the present study, the microflora found in the symptomatic teeth at the species level were Propionibacterium acidifaciens and Propionibacterium propionicum, which were different from the species (Peptostreptococcus, Prevortella, and Porphyromonas spp.) found in the previous studies.2-4,9,20 This might be due to the accuracy of the present sequencing technique.11 In the present study, symptomatic teeth mostly had longer and steeper rarefaction curves than those of the asymptomatic teeth. This means that the symptomatic teeth still have more bacterial communities need to be found in their root canals. In conclusion, the current generation GS FLX Titanium pyrosequencing demonstrated a very high bacterial diversity in primary endodontic infections, indicating that the etiology of primary apical periodontitis is much more complex than anticipated. Further study to compare the microbial profile in refractory apical periodontitis should be followed to find out their functional roles in endodontic microbial community.

Figures and Tables

| Figure 1Plots of the numbers of different operational taxonomic units (OTUs) in infected root canals from symptomatic and asymptomatic teeth. The steepness and length of the curve indicates that a large fraction of the species diversity has not sampled. PN, asymptomatic canal; PY, symptomatic canal. |

| Figure 2Bacterial abundance and prevalence distribution at phylum level. PN, asymptomatic canal; PY, symptomatic canal. |

| Figure 3The 10 most abundant genera identified in asymptomatic teeth (a, PN) and the 10 most abundant genera in symptomatic teeth (b, PY) with their abundance values. |

Table 1

Sequencing information for the bacteria in asymptomatic and symptomatic teeth with primary apical periodontitis

aTrimmed reads that passed quality control as described in Huse SM et al.15

References

1. Kakehashi S, Stanley HR, Fitzgerald RJ. The effects of surgical exposures of dental pulps in germ-free and conventional laboratory rats. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1965. 20:340–349.

2. Gomes BP, Drucker DB, Lilley JD. Associations of specific bacteria with some endodontic signs and symptoms. Int Endod J. 1994. 27:291–298.

3. Gomes BP, Lilley JD, Drucker DB. Associations of endodontic symptoms and signs with particular combinations of specific bactreria. Int Endod J. 1996. 29:69–75.

4. Yoshida M, Fukushima H, Yamamoto K, Ogawa K, Toda T, Sagawa H. Correlation between clinical symptoms and microorganism isolated from root canal of teeth with periapical pathosis. J Endod. 1987. 13:24–28.

5. Rôças IN, Siqueira JF Jr. Root canal microbiota of teeth with chronic apical periodontitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2008. 46:3599–3606.

6. Siqueira JF Jr, Roôças IN. Community as the unit of pathogenicity: an emerging concept as to the microbial pathogenesis of apical periodontitis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009. 107:870–878.

7. Kim SY, Choi HY, Park SH, Choi GW. Distribution of oral pathogens in infection of endodontic origin. J Korean Acad Conserv Dent. 2003. 28:303–313.

8. Kum KY, Fouad AF. PCR-based identification of Eubacteirum species in endodontic infection. J Korean Acad Conserv Dent. 2003. 28:241–248.

9. Lee YJ, Kim MK, Hwang HK, Kook JK. Isolation and identification of bacteria from the root canal of the teeth diagnosed as the acute pulpitis and acute periapical abscess. J Korean Acad Conserv Dent. 2005. 30:409–422.

10. Siqueira JF Jr, Rôças IN. Diversity of endodontic microbiota revisited. J Dent Res. 2009. 88:969–981.

11. Keijser BJ, Zaura E, Huse SM, van der Vossen JM, Schuren FH, Montijn RC, ten Cate JM, Crielaard W. Pyrosequencing analysis of the oral microflora of healthy adults. J Dent Res. 2008. 87:1016–1020.

12. Horz HP, Vianna ME, Gomes BP, Conrads G. Evaluation of universal probes and primer sets for assessing total bacterial load in clinical samples: general implications and practical use in endodontic antimicrobial therapy. J Clin Microbiol. 2005. 43:5332–5337.

13. Weisburg WG, Barns SM, Pelletier DA, Lane DJ. 16S ribosomal DNA amplication for phylogenetic study. J Bacteriol. 1991. 173:697–703.

14. Huse SM, Huber JA, Morrison HG, Sogin ML, Welch DM. Accuracy and quality of massively parallel DNA pyrosequencing. Genome Biol. 2007. 8:R143.

15. Li L, Hsiao WW, Nandakumar R, Barbuto SM, Mongodin EF, Paster BJ, Fraser-Liggett CM, Fouad AF. Analyzing endodontic infections by deep coverage pyrosequencing. J Dent Res. 2010. 89:980–984.

16. Lee TK, Van Doan T, Yoo K, Choi S, Kim C, Park J. Discovery of commonly existing anode biofilm microbes in two different wastewater treatment MFCs using FLX Titanium pyrosequencing. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010. 87:2335–2343.

17. Brockman W, Alvarez P, Young S, Garber M, Giannoukos G, Lee WL, Russ C, Lander ES, Nusbaum C, Jaffe DB. Quality scores and SNP detection in sequencing-by-synthesis system. Genome Res. 2008. 18:763–770.

18. Chun J, Lee JH, Jung Y, Kim M, Kim S, Kim BK, Lim YW. EzTaxon: a web-based tool for the identification of prokaryotes based on 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequences. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007. 57:2259–2261.

19. Siqueira JF Jr, Rôças IN, Paiva SS, Magalhães KM, Guimarães-Pinto T. Cultivable bacteria in infected root canals as identified by 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2007. 22:266–271.

20. Vickerman MM, Brossard KA, Funk DB, Jesionowski AM, Gill SR. Phylogenetic analysis of bacterial and archaeal species in symptomatic and asymptomatic endodontic infections. J Med Microbiol. 2007. 56:110–118.

21. Siqueira JF Jr, Alves FR, Rôças IN. Pyrosequencing analysis of the apical root canal microbiota. J Endod. 2011. 37:1499–1503.

22. Zaura E, Keijser BJ, Huse SM, Crielaard W. Defining the healthy "core microbiome" of oral microbial communities. BMC Microbiol. 2009. 9:259.

23. Lazarevic V, Whiteson K, Hernandez D, François P, Schrenzel J. Study of inter- and intra-individual variations in the salivary microbiota. BMC Genomics. 2010. 11:523.

24. Lazarevic V, Whiteson K, Huse S, Hernandez D, Farinelli L, Osterås M, Schrenzel J, François P. Metagenomic study of the oral microbiota by Illumina high-throughput sequencing. J Microbiol Methods. 2009. 79:266–271.

25. Nercessian O, Fouquet Y, Pierre C, Prieur D, Jeanthon C. Diversity of Bacteria and Archaea associated with a carbonate-rich metalliferous sediment sample from the Rainbow vent field on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Environ Microbiol. 2005. 7:698–714.

26. Signoretto C, Burlacchini G, Bianchi F, Cavalleri G, Canepari P. Differences in microbiological composition of saliva and dental plaque in subjects with different drinking habits. New Microbiol. 2006. 29:293–302.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download