Abstract

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether rhBMP-2 (BMP2) could induce synergistic effect with Pro-Root® MTA (MTA) in pulpotomized teeth in the rats. Healthy upper first molars from thirty-two, 10 weeks old, Sprague-Dawley rats were used for this investigation. The molars were exposed with round bur, and light pressure was applied with sterilized cotton to control hemorrhage. 1.2 grams of MTA cement was placed in right first molars as a control group. In left first molars, 1 µg of BMP2 was additionally placed on exposed pulps with MTA. All cavities were back-filled with light-cured glass-ionomer cements. The rats were sacrificed after 2 weeks and 7 weeks, respectively. Then histologic sections were made and assessed by light microscopy. Data were statistically analyzed via student t-test with SPSSWIN 12.0 program (p < 0.05).

Inflammation observed in 2 weeks groups were severe compared to the 7 weeks groups. But the differences were not statistically significant. BMP2-addition groups had less inflammation than MTA groups in both periods, though these differences were also not statistically significant. In conclusion, the combination of BMP2 and MTA showed no differences with MTA only for pulpotomy of rat teeth.

The goal of treating exposed pulp with an appropriate material for vital pulp therapy is to promote the regeneration of dental pulp cells1). Wound healing and new hard tissue formation beneath the injury are prerequisites for long-term control of pulp survival in vital pulp therapy. Successful outcome for vital pulp therapy is very dependent on the type and location of injury, development of the tooth, capping material and integrity of the cavity restoration2).

Formocresol has long been the standard pulpotomy agent in primary teeth, and calcium hydroxide in immature permanent teeth. However they have some disadvantages to be used as a pulpotomy agent3). Advance in material and biological sciences offered better treatment modalities to us in vital pulp therapy.

Mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) cement has recently been introduced to clinical dentistry4). MTA showed good outcomes in pulpotomy of primary teeth5), and has been used in pulp-capping procedures in animals, demonstrating remarkable success compared with calcium hydroxide6-8). Better results of cell response were found in the presence of MTA9-11). Some studies have demonstrated that the antibacterial effects of MTA are comparable to those of calcium hydroxide12-14). And some researches demonstrated MTA induced better results than calcium hydroxide as an agent for vital pulp therapy8,15). But there are no long-term results on the effectiveness of MTA as an agent for vital pulp therapy.

For better results in vital pulp therapy, several authors have encouraged the evaluation of growth factors like bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) as morphogens16,17). These proteins are osteogenic proteins, originally identified as the active components within osteoinductive extracts derived from bone, which is able to stimulate osteoblast differentiation and bone formation at ectopic sites18,19). Implications of these proteins to dentistry are enormous, including orthopedic, oral and periodontal surgeries, and vital pulp therapy and so on. Several BMPs have been used experimentally, with the aim of introducing reparative dentinogenesis in the dental pulp20-22).

In this respect, we used rhBMP-2 (BMP2) combined with clinically accepted material, MTA, as a pulpotomy material. The purpose of this study was to investigate whether BMP2 could induce synergistic effect with MTA in pulpotomized teeth in the rats.

The animal experimental protocol was approved by the Animal Research Committee of Asan Medical Center (Seoul, Korea) and all ethical criteria contained in Helsinky declaration. Healthy non-carious upper first molars from thirty-two, 10 weeks old, Sprague-Dawley rats were used for this investigation. All procedures were performed under anesthesia using intraperitoneal injection of ketamin (90 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). The teeth were washed with 0.5% chlorhexidine. Access cavities were prepared through the occlusal surface using a sterile high-speed 1/4 round bur. Bleeding was controlled by light pressure with sterile cotton pellets and paper points before placing the materials. No salivary contamination was allowed.

The materials used in this study were ProRoot® MTA (MTA, ProRoot®, Dentsply Tulsa, Tulsa, OK, USA) and recombinant human Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 (BMP, R&D Systems lnc. Minneapolis, MN, USA). 1.2 grams of MTA cement was mixed according to manufacturer's instructions. MTA was placed in upper right first molars as a control group. In upper left first molars, 1 µg of BMP2 was placed on exposed pulps followed by a restoration of MTA. All cavities were restored with light-cured glass-ionomer cements (Fuji II LC®, GC Co. Tokyo, Japan). After 2 weeks, sixteen rats were sacrificed by subcutaneous injection of an overdose of pentobarbital sodium and perfused with 10% buffered formalin through the aorta. The other sixteen rats were sacrificed after 7 weeks by same manner. The teeth were divided into four groups.

Group I - 2 weeks with MTA (n = 16)

Group II - 2 weeks with MTA & BMP (n = 16)

Group III - 7 weeks with MTA (n = 16)

Group IV - 7 weeks with MTA & BMP (n = 16)

Then upper molars and their associated periodontal supporting tissues were dissected out and fixed in 10% buffered formalin. The sections were decalcified with 10% EDTA for 5 - 7 days. The teeth were processed by standard paraffin embedding procedures and at least five 5 µm thick stepserial sections per tooth were taken at 0.5 to 1.0 mm intervals. The resultant sections were stained by hematoxylin and eosin.

Histological changes of teeth were evaluated under light microscope (Nikon Eclipse TE 200, Tokyo, Japan). The two endodontists were blinded to the treated groups and evaluated the histological sections according to the following category.

Grade 0; no inflammation and occurring hard tissue repair in pulp chamber

Grade 1; mild inflammation in pulp area

Grade 2; moderate inflammation in pulp area

Grade 3; severe inflammation in pulp area or microabscess

Data were statistically analyzed via student t-test with SPSSWIN 12.0 program (p < 0.05).

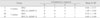

Inflammation observed in 2 weeks groups were severe compared to the 7 weeks groups. So, inflammation scores were higher in group I & II as compared to group III & IV (Table 1). But these differences were not statistically significant. BMP2 groups had less inflammation than MTA groups in both periods, but these differences were also not statistically significant (p < 0.05). The degree of inflammation of four groups is summarized in Table 1.

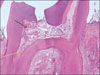

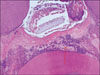

In 2 weeks groups, most of histological sections had zones of some inflammation. The slightly heavily inflammed tissue was composed of many infiltrated inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes, macrophages and plasma cells in group I (Figure 1-A, 1-B). Most specimens of group I and II showed some intracanal hard tissue formation, but complete dentinal bridge was not formed at any specimen (Figure 2-A, 2-B).

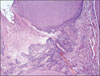

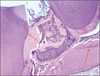

In 7 weeks groups, inflammation was reduced than that of 2 weeks groups, but the specimens still showed mild inflammation. In group III and IV, most of specimens indicated nearly complete formation of dentinal bridge (Figure 3-A, 4-A) and the type of hard tissue that is newly formed was osteodentin, including cell body, rather than true dentin in group III and IV (Figure 3-B, 4-B). The amounts of hard tissue formation were similar between group III and group IV.

Growth factors are polypeptides that increase cell replication and have important effects on differentiated cell function23). And it was reported that a few growth factors were used in animal studies for endodontic treatment24,25). Bone morphogenetic factors (BMPs) are growth factors belonging to the TGF-β superfamily26). BMPs have been implicated in tooth development, and the expression of BMP2 is increased during the terminal differentiation of odontoblasts27,28). Under pathologic conditions such as carious lesions, the secretory activity of odontoblasts is stimulated to produce dentin via a process that may be exerted by signaling molecules, like BMPs, liberated from the dentin during demineralization29). BMP2 also induces a large amount of reparative dentin on the amputated pulp in vivo27).

Conventional endodontic therapy has been reported to show a high success rate30). But, many teeth are not restorable, and vital pulp therapy is not always predictable. The dental pulp contains progenitor/stem cells, which can proliferate and differentiate into dentin-forming odontoblasts. And it was reported that BMP2 could direct pulp progenitor/stem cell differentiation into odontoblasts and result in dentin formation31).

BMP's multiple effects on inducible cell populations include mitotic effects on undifferentiated mesenchymal cells and osteoblast precursors; induction of expression of the osteoblast phenotype; chemoattractiveness to mesenchymal cells and monocytes and binding to extracellular matrix type IV collagen26). But the exact molecular control mechanism of BMP is still not clear.

MTA was chosen for this study because of its proven hard tissue-forming capabilities6-8). MTA cement powder consists of fine hydrophilic particles mainly containing tricalcium silicate, tricalcium aluminate, tricalcium oxide and bismuth oxide. MTA sets in the presence of moisture, prevents microleakage, is biocompatible, and promotes reparative dentin formation4-8,12-15). MTA has been found to induce a significantly greater frequency of dentin bridge formation, less pulp inflammation, and bridges with significantly greater than mean thickness compared with calcium hydroxide6-8). But there is no data in long-term result of MTA using in vital pulp therapy.

We expected that BMP2 could induce the synergistic effect with MTA in reparative dentin formation. This assumption was based on the earlier finding by us that the cytotoxicity of MTA and combination treatment of MTA & BMP decreased with passage of time32). So, the addition of BMP to MTA has a beneficial effect to reduce initial cytotoxicity of freshly mixed MTA cement32).

However, in this study, between MTA and BMP groups there were no statistically significant differences in pulpal inflammation and formation of reparative dentin. The different outcomes between two studies may be due to the effect of dosage or local tissue concentration of BMP2. But, in another study using BMP7, BMP7 was not dose-dependent in inducing reparative dentinogenesis33). Further study is necessary to evaluate if the outcome of vital pulp therapy is affected by the dosage of BMP2. And we speculate that BMP2 could have been denaturated due to high pH of MTA on before-setting. Also the half-life of BMPs is limiting, so high concentration is required in addition to an optimal carrier during the local application to the exposed pulp for reparative dentin formation27).

In our results, newly formed dentin matrix was almost osteodentin. Nakashima reported22) that tubular dentin formation was induced when BMP2 implanted on the amputated pulp with 4M-guanidine chloride extracted inactivated demineralized dentin matrix. During the early steps of reparative dentin formation, odontoblast-like cells are embedded in the dentin bridge. Therefore, the reparative structure is initially of the osteodentin type, whereas later the reparative dentin appears to be of the tubular dentin type, with tubules and without cell body inclusions34).

In this study, most of specimens indicated nearly complete formation of dentinal bridge in 7 weeks groups. And the type of hard tissue that is newly formed was osteodentin. There were also no obstruction signs of entire pulp canals. These could be hopeful signs of regenerating pulp tissues. Although the current study did not demonstrate improved healing with BMP2, the future regimens of vital pulp therapy are likely to be based on physiological strategies using biomolecules such as BMPs. And additional research is needed to confirm if the differences come from the kind of the growth factors or filling materials.

Figures and Tables

Figure 1-A

Histological specimen of MTA-pulpotomized tooth (2 weeks, × 100)

Black arrow: Capping materials, Blue arrow: Inflammation zone, Yellow arrow: Early stage of hard tissue formation.

Figure 1-B

Histological specimen of MTA-pulpotomized tooth (2 weeks, × 400)

Red arrow: Inflammation zone was filled with many inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes, macrophages and plasma cells.

Figure 2-A

Histological specimen of MTA&BMP2-pulpotomized tooth (2 weeks, × 100)

Black arrow: Pulp capping materials, Blue arrow: Inflammation zone, Yellow arrow: Some vessels were dilated in pulp tissue.

Figure 2-B

Histological specimen of MTA&BMP2-pulpotomized tooth (2 weeks, × 400)

Red arrow: Inflammation zone was composed of inflammatory cells.

Figure 3-A

Histological specimen of MTA-pulpotomized tooth (7 weeks, × 100)

Black arrow: Pulp capping materials, Blue arrows: Hard tissue formation, Yellow circle: Dentinal bridge formation.

Figure 3-B

Histological specimen of MTA-pulpotomized tooth (7 weeks, × 400).

Red arrows: Newly formed hard tissues. Morphologies of new dentinal tubules are different from old those.

Figure 4-A

Histological specimen of MTA&BMP2-pulpotomized tooth (7 weeks, × 100).

Black arrow: Pulp capping materials, Blue arrow: Hard tissue formation, Yellow circle: Dentinal bridge formation, Red arrow: Slightly inflammed pulp tissue.

Figure 4-B

Histological specimen of MTA&BMP2-pulpotomized tooth (7 weeks, × 400).

Yellow arrow: Hyalinization of surrounding materials, Red arrow: Newly formed dentinal bridge. The type of hard tissue that is newly formed was osteodentin, including cell body, rather than true dentin, Blue arrow: Slightly inflammed pulp tissue.

References

1. Schroder U. Effects of calcium hydroxide-containing pulp-capping agents on pulp cell migration, proliferation, and differentiation. J Dent Res. 1985. 64:541–548.

2. Tziafas D. The future role of a molecular approach to pulp-dentinal regeneration. Caries Res. 2004. 38:314–320.

3. Ranly DM, Garcia-Godoy FJ. Current and potential pulp therapies for primary and young permanent teeth. J Dent. 2000. 28:153–161.

4. Torabinejad M, Chivian N. Clinical applications of mineral trioxide aggregate. J Endod. 1999. 25:197–205.

5. Peng L, Ye L, Tan H, Zhou X. Evaluation of the formocresol versus mineral trioxide aggregate primary molar pulpotomy: a meta-analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006. 102:e40–e44.

6. Abedi HR, Torabinejad M, Pitt Ford TR. Using mineral trioxide aggregate as a pulp-capping material. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996. 127:1491–1494.

7. Ford TR, Torabinejad M, Abedi HR, Bakland LK, Kariyawasam SP. Using mineral trioxide aggregate as a pulp-capping material. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996. 127:1491–1494.

8. Faraco IM, Holland R. Response of the pulp of dogs to capping with mineral trioxide aggregate or a calcium hydroxide cement. Dent Traumatol. 2001. 17:163–166.

9. Mitchell PJ, Pitt Ford TR, Torabinejad M, McDonald F. Osteoblast biocompatibility of mineral trioxide aggregate. Biomaterials. 1999. 20:167–173.

10. Koh ET, McDonald F, Pitt Ford TR, Torabinejad M. Cellular response to Mineral Trioxide Aggregate. J Endod. 1998. 24:543–547.

11. Koh ET, Torabinejad M, Pitt Ford TR, Brady K, McDonald F. Mineral trioxide aggregate stimulates a biological response in human osteoblasts. J Biomed Mater Res. 1997. 37:432–439.

12. Torabinejad M, Rastegar A, Kattering J, Pitt Ford TR. Bacterial microleakage of mineral trioxide aggregate as a root-end filling material. J Endod. 1995. 21:109–112.

13. Al-Nazhan S, Al-Judai A. Evaluation of antifungal activity of mineral trioxide aggregate. J Endod. 2003. 29:826–827.

14. Al-Hezaimi K, Al-Shalan TA, Naghshbandi J, Oglesby S, Simon JH, Rotstein I. Antibacterial effect of two mineral trioxide aggregate(MTA) preparations against Enterococcus Faecalis and Streptococcus sanguis in vitro. J Endod. 2006. 32:1053–1056.

15. Aeinehchi M, Eslami B, Ghanbariha M, Saffar AS. Mineral trioxide aggregate(MTA) and calcium hydroxide as pulp capping agents in human teeth; a preliminary report. Int Endod J. 2003. 36:225–231.

16. Nakashima M, Akamine A. The application of tissue engineering to regeneration of pulp and dentin in endodontics. J Endod. 2005. 31:711–718.

17. Sloan AJ, Smith AJ. Stem cells and the dental pulp:potential roles in dentine regeneration and repair. Oral Dis. 2007. 13:151–157.

18. Wozney JM. The bone morphogenetic protein family: multifunctional cellular regulators in the embryo and adult. Eur J Oral Sci. 1998. 106:160–166.

19. Lianjia Y. Immunohistochemical localization of bone morphogenetic protein(BMP) in calcifying fibrous epulis. J Oral Pathol Med. 1993. 22:406–410.

20. Tziafas D, Kolokuris I. Inductive influences of demineralized dentin and bone matrix on pulp cells: an approach of secondary dentinogenesis. J Dent Res. 1990. 69:75–81.

21. Smith AJ, Tobias RS, Cassidy N, Begue-Kirn C, Ruch JV, Lesot H. Influence of substrate nature and immobilization of implanted dentin matrix components during induction of reparative dentinogenesis. Connect Tissue Res. 1995. 32:291–296.

22. Nakashima M. Induction of dentin formation on canine amputated pulp by recombinant human bone morphogenetic proteins (BMP)-2 and -4. J Dent Res. 1994. 73:1515–1522.

23. Canalis E, McCarthy T, Centrella M. Growth factors and the regulation of bone remodelling. J Clin Invest. 1988. 81:277–281.

24. Hu CC, Zhang C, Quan Q, Tatum NB. Reparative dentin formation in rat molars after direct pulp capping with growth factors. J Endod. 1998. 24:744–751.

25. Kim MR, Kim BH, Yoon SH. Effect on the healing of periapical perforations in dogs of the addition of growth factors to calcium hydroxide. J Endod. 2001. 27:734–737.

27. Nakashima M. Induction of dentine in amputated pulp of dogs by recombinant human bone morphogenetic proteins-2 and -4 with collagen matrix. Arch Oral Biol. 1994. 39:1085–1089.

28. Nakashima M, Reddi AH. The application of bone morphogenetic proteins to dental tissue engineering. Nat Biotechnol. 2003. 21:1025–1032.

29. Bègue-Kirn C, Smith AJ, Loriot M, Kupferle C, Ruch JV, Lesot H. Comparative analysis of TGF-βs, BMPs, IGF, msxs, fibronectin, osteonectin and bone sialoprotein gene gene expression during normal and in vitro induced odontoblast differentiation. Int J Dev Biol. 1994. 38:405–420.

30. Torabinejad M, Kutsenko D, Machnick T, Ismail A, Newton CW. Levels of evidence for the outcome of nonsurgical endodontic treatment. J Endod. 2005. 31:637–646.

31. Iohara K, Nakashima M, Ito M, Ishikawa M, Nakashima A, Akamine A. Dentin regeneration by dental pulp stem cell therapy with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein 2. J Dent Res. 2004. 83:590–595.

32. Kim MR, Ko HJ, Yang WK, Kim WK, Lee YK. Cytotoxicity of ProRoot® MTA cement with rhBMP-2. J Korean Acad Endod. 2006. 7:39–49.

33. Six N, Lasfargues JJ, Goldberg M. Differential repair responses in the coronal and radicular areas of the exposed rat molar pulp induced by recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein 7 (osteogenic protein 1). Arch Oral Biol. 2002. 47:177–187.

34. Goldberg M, Six N, Decup F, Lasfargues JJ, Salih E, Tompkins K, Veis A. Bioactive molecules and the future of pulp therapy. Am J Dent. 2003. 16:66–76.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download