Abstract

The purposes of this study were to compare the effects of one or two applications of all-in-one adhesives on microtensile bond strengths (µTBS) to unground enamel and to investigate the morphological changes in enamel surfaces treated with these adhesives using a scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

Twenty-five noncarious, unrestored human mandibular molars were used. The unground enamel surfaces were cleansed with pumice. The following adhesives were applied to lingual, mid-coronal surfaces according to manufacture's directions; Clearfil SE bond in SE group, Adper Prompt L-Pop™1 coat in LP1 group, 2 coats in LP2 group, Xeno® III 1 coat in XN1 group, and 2 coats in XN2 group. After application of the adhesives, a hybrid light-activated resin composite was built up on the unground enamel. Each tooth was sectioned to make a cross-sectional area of approximately 1.0 mm2 for each stick. The microtensile bond strength was determined. Each specimen was observed under SEM to examine the morphological changes. Data were analyzed with one-way ANOVA.

The results of this study were as follows;

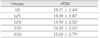

1. The microtensile bond strength values were; SE (19.77±2.44 MPa), LP1 (13.88±3.67 MPa), LP2 (14.50±2.52 MPa), XN1 (14.42±2.51 MPa) and XN2 (15.28±2.79 MPa). SE was significantly higher than the other groups in bond strength (p < 0.05). All groups except SE were not significantly different in bond strength (p < 0.05).

2. All groups were characterized as shallow and irregular etching patterns.

Enamel adhesion is one of the important factors for the longevity of restorations because failure of sealing in the enamel margin leads to leakage of oral fluid and bacterial invasion, and finally results in hypersensitivity and secondary caries. Marginal discoloration and recurrent caries are the most frequent reasons for replacement of resin composite restorations1).

Opdam et al.2) reported that the Class II resin composite restorations placed in vivo are frequently found (i.e., 43%) to have overextended cervical margins. It is often difficult to remove the overextended cervical margins of approximal restorations without damaging the gingival tissues. In addition, some operators preferred to etch and bond materials over the existing enamel without removing any tooth structure when performing a laminated veneer restoration or diastema closure work3). Thus, optimal bonding to unground enamel, as well as ground enamel, is important to obtain good clinical performance of resin composite restorations. Most of the adhesive restorative materials are developed through bonding tests to ground enamel surfaces4). However, not all enamel margins are prepared. Therefore, the bonding performance of the current adhesive systems should be evaluated on the unground enamel surfaces.

Many types of resin bonding systems have been developed in the last decade, however, current resin bonding systems can generally be divided into etch and rinse, self-etching primer and self-etching adhesive in terms of means to achieve the goal of micromechanical retention between resin and dentin5). Contemporary self-etching primers and the recently introduced all-in-one adhesives are attractive additions to the clinician's bonding armamentarium. They are user-friendly in that the number of steps required in the bonding protocol is reduced.

Introduced in 1955 by Buonocore6), enamel etching is conventionally achieved by phosphoric acid conditioning to cause preferential dissolution of interprismatic enamel, allowing micro-mechanical retention by adhesive resins7). Bond strength is reported to correspond to intraprismatic penetration of resin tags, highlighting the importance of a successful etching regimen8). However, in most studies, when self-etching adhesives are used, shallow and irregular etching patterns are observed on intact enamel9, 10). Also Kanemura et al.11) concluded that the self-etching adhesives had low bond strengths to intact enamel. On the other hand, self-etching adhesives have been reported to bond well to normal dentin and ground enamel12). In addition, multiple consecutive applications of adhesives on dentin surface have increased bond strengths13).

The purposes of this study were to compare the effects of one or two applications of all-in-one adhesive on microtensile bond strengths(µTBS) to unground enamel and to investigate the morphological changes in enamel surfaces treated with these adhesives using a scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

The two adhesives evaluated were an unfilled, all-in-one adhesive, Adper Prompt L-Pop™ (3M Dental Products, St. Paul, MN, USA) and a filled, all-in-one adhesive, Xeno® III (Densply Caulk, Milford, DE, USA). In addition, two-step self-etching primer, Clearfil™ SE Bond (Kurarary Medical Inc., Okayama, Japan) was used as a control. The compositions of these adhesives are shown in Table 1.

Twenty-five noncarious, unrestored human mandibular molars that were extracted for periodontal problems were used in this study. The unground enamel surfaces were cleansed with pumice using a rubber cup engaged in a slow speed dental handpiece. Because of the need for a flat enamel surface, the mid-coronal portion of lingual surface of these teeth was utilized for all bonding experiments.

Fifteen molars were used for this part of the experiment. All teeth were randomly divided into five groups so that each group contained three teeth. In group SE, Clearfil™ SE Bond was applied. In group LP1, Adper Prompt L-Pop™ was applied and light-cured. In group LP2, after light-curing the first layer, the adhesive was reapplied. In group XN1, Xeno® III was applied and light-cured. And in group XN2, after light-curing the first layer, the adhesive was re-applied and light-cured. The five groups were etched and bonded in the manner described in Table 2. A hybrid light-activated resin composite, Z100 (A2; 3M Dental Products, St. Paul, MN, USA) was built up incrementally in five layers. Each increment was 2 mm and light-cured for 20 s. The bonded teeth were then stored in distilled water at 37℃ for 24 h prior to sectioning.

Each tooth was sectioned using a high speed precision cut-off machine (Accutom-50; Struers, Ballerup, Denmark) under water lubrication to make a cross-sectional area of approximately 1.0 mm2 for each stick. Ten sticks for each group were used for µTBS test. The stick was fixed to the test bed using cyanoacrylate adhesive (Zapit; DVA, Corona, CA, USA). The sticks were pulled to failure under tension using a Micro Tensile Tester (Bisco inc., Schaumburg, IL, USA) at a crosshead speed of 1 mm/min.

Bond strength data obtained for the five groups (SE, LP1, LP2, XN1 and XN2) were analyzed with the SPSS 12.0K for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Duncan's post-hoc test was computed.

Lingual enamel surfaces of the two teeth from each group were conditioned with the self-etching adhesives, in a same manner described in Table 2. In LP2 and XN2 groups, however, the enamel surfaces were applied consecutive coat without light-curing the first layer. Enamel etched with self-etching adhesive was rinsed with acetone for 10 s to remove the self-etching adhesive. Then, the specimens were dehydrated with an ascending series of ethanol (70, 80, 90 and 100%) for 1 min each. All the teeth were allowed to air-dry. They were secured to aluminum stubs, sputtered coated with gold/palladium and examined using a scanning electron microscope (S-4200; HITACHI, Tokyo, Japan) operation at 15 kV. The mid-coronal part of the lingual etched surface of each tooth was examined (× 1000).

Table 3 lists the µTBS of the all-in-one adhesives (Group LP1, LP2, XN1 and XN2) as well as the control two-step self-etching primer (Group SE) on unground enamel. The mean bond strength of the SE group was 19.77 MPa and that of the other groups varied between 13.88 and 15.28 MPa. Statistically significant differences were found between group SE and the other groups (p < 0.05).

SEM images of unground enamel surfaces, treated with the adhesives, are shown in Figure 1. Unground enamel surfaces did not have different surface morphologies depending on whether they were etched one or two times. A non-uniform etched pattern was exhibited with the use of all adhesives. Prismatic structures of enamel were not clearly observed.

Bonding to the unground enamel surface is important to prevent marginal microleakage and for the retention of pit and fissure sealants. In addition, clinically, not all enamel margins are prepared11). Therefore, we have to test about bond strength to the unground enamel surfaces as well as ground surfaces.

Recently introduced all-in-one adhesives simplified clinical applications and reduced post-operative sensitivity and technique sensitivity. However, recent studies showed that some all-in-one adhesives exhibited relatively low bond strengths when compared with phosphoric acid etching9) and two-step self-etching systems14). In dentin bonding, this problem was overcome by multiple applications of adhesives15).

Therefore, in this study, we investigated the effects of one or two applications of all-in-one adhesive on microtensile bond strength to unground enamel. According to the result of this study, there were significant differences in the microtensile bond strength to unground enamel treated with either Clearfil™ SE bond or Prompt L-Pop™, Xeno® III. Our results confirmed those of Senawongse et al.3), who reported significant differences between unground enamel-resin bonds produced following two-step self-etching primers versus all-in-one adhesives. Nikaido et al.16) suggested that double application of a self-etching primer improved the bond strength of paste-type resin-modified glass ionomer cements and resin composite to enamel. According to our results, however, there were no significant differences in the effects of one or two coats of all-in-one adhesive on microtensile bond strength to unground enamel. Consequently, in contrast to multiple applications increased the bond strength in dentin surfaces, there were no increase in unground enamel bond strength.

The unground enamel surface is hypermineralized and contains more fluoride than ground enamel. This infers that saturated calcium phosphate in the saliva might hypermineralize the enamel, and fluorine ions can convert the hydroxyapatite into fluoroapatite17). Hence, in this layer, the etching effects relatively were less than those on ground enamel and dentin surface18).

The abilities of etching the aprismatic enamel surface were affected by the pH and the etching time of acid19). However, a thick prismless enamel layer may prevent the permeation of all-in-one adhesives, thus leaving some areas partially unetched20). Because the etching abilities of all-in-one adhesives are insufficient, penetration of the adhesive resin into microporosities of unground enamel surface are deficient. In addition, the manufacturer-recommended etching time was short to demineralize the enamel surface21). Ferrari et al.22) concluded that the performance of the all-in-one adhesive provided adequate marginal seals of Class V cavities both in vitro and in vivo when the all-in-one adhesive is applied for 60 s instead of the manufacturer-recommended 30 s etch. For this reasons, we concluded that all-in-one adhesives did not have sufficient bond strength at the initial adhesive layer, thus the second application of these adhesives did not affect to the bond strength on unground enamel surface.

Miyazaki et al.23) concluded that the adequate filler level (i.e., 10 wt%) in bonding agent optimized the dentin bond strength. In our study, however, there were statistically no significant differences between unfilled groups and filled groups. It may be related to the chemical and micromorphologic differences between intact unground enamel and ground enamel24).

Kanemura et al.11) showed that the etching pattern of all-in-one adhesives was not deep enough to obtain good penetration of bonding resin when applied to unground enamel. Similarly, the SEM evaluation of this study revealed that the etching patterns in all groups were shallow, poorly defined, and structurally incomplete.

Within the limits of this study, it may be concluded that the two all-in-one adhesives examined produced low microtensile bond strengths to unground enamel. There was no correlation between their number of application times and the strength of their bonds to unground enamel. In addition, the etching pattern of all-in-one adhesives was shallow and irregular.

Therefore, improvements may be necessary in the formulations of all-in-one adhesives or in the instructions for their use in order to achieve optimal bond strengths to unground enamel surface.

Figures and Tables

| Figure 1The SEM photographs show unground enamel surface treated with the two-step self-etching primer, Clearfil™ SE Bond (a), the unfilled, all-in-one adhesive, Adper Prompt L-Pop™ (b; 1 coat, c; 2 coats) and the filled, all-in-one adhesive, Xeno® III (d; 1 coat, e; 2 coats) (× 1000). |

References

1. Friedl KH, Hiller KA, Schmalz G. Placement and replacement of composite restorations in Germany. Oper Dent. 1995. 20:34–38.

2. Opdam NJM, Roeters FJM, Feilzer AJ, Smale I. A radiographic and scanning electron microscopic study of apporximal margins of Class II resin composite restorations placed in vivo. J Dent. 1998. 26:319–327.

3. Senawongse P, Sattabanasuk V, Shimada Y, Otsuki M, Tagami J. Bond strengths of current adhesive systems on intact and ground enamel. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2004. 16:107–116.

4. Chigira H, Yukitani W, Hasegawa T, Manabe A, Itoh K, Hayakawa T, Debari K, Wakmoto S, Hisamitu H. Self-etching dentin primers containgin Phenyl-P. J Dent Res. 1994. 73:1088–1095.

6. Buonocore MG. A simple method of increasing the adhesion of acrylic filling materials to enamel surfaces. J Dent Res. 1955. 34:849–853.

7. Pilecki P, Stone DG, Sherriff M, Watson TF. Microtensile bond strengths to enamel of self-etching and one bottle adhesive systems. J Oral Rehabil. 2005. 32:531–540.

8. Ten Cate JM, Keizer S, Arends J. Polymer adhesion to enamel. The influence of viscosity and penetration. J Oral Rehabil. 1977. 4:149–156.

9. Perdigao J, Geraldeli S. Bonding characteristics of self-etching adhesives to intact versus prepared enamel. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2003. 15:32–41.

10. Oh SK, Hur B, Kim HC. The etching effects and microtensile bond strength of total etching and self-etching adhesive system on unground enamel. J Korean Acad Conserv Dent. 2004. 29:273–280.

11. Kanemura N, Sano H, Tagami J. Tensile bond strength to and SEM evaluation of ground and intact enamel surfaces. J Dent. 1999. 27:523–530.

12. Perdigao J, Duarte S Jr. Enamel bond strengths of pairs of adhesives from the same manufacturer. Oper Dent. 2005. 30:492–499.

13. Hashimoto M, Sano H, Yoshida E, Hori M, Kaga M, Oguchi H, Pashley DH. Effects of multiple adhesive coatings on dentin bonding. Oper Dent. 2004. 29:416–423.

14. Fritz UB, Finger WJ. Bonding efficiency of single-bottle enamel/dentin adhesives. Am J Dent. 1999. 12:277–282.

15. Frankenberger R, Perdigao J, Rosa BT, Lopes M. No-bottle vs. Multi-bottle dentin adhesives-a microtensile bond strength and morphological study. Dent Mater. 2001. 17:373–380.

16. Nikaido T, Nakajima M, Higashi T, Kanemura N, Pereira P, Tagami J. Shear bond strength of a single-step bonding system to enamel and dentin. Dent Mater J. 1997. 16:40–47.

17. Sturdevant CM, Barton RE, Sockwell CL, Strickland WD. The art and science of operative dentistry. 1985. 2nd ed. St. Louis, Missouri: The C.V. Mosby Co.;54–55.

18. Nathanson D, Bodkin JL, Evans JR. SEM of etching patterns in surface and subsurface enamel. J Pedod. 1982. 7:11–17.

19. Cehreli ZC, Altay N. Effects of a non-rinse conditioner and 17% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid on the etch pattern of intact human permanent enamel. Angle Orthodont. 2000. 70:22–27.

20. Gwinnett AJ. The ultrastructure of prismless enamel of permanent teeth. Arch Oral Biol. 1967. 12:381–386.

21. Finger WJ, Fritz U. Laboratory evaluation of one-component enamel/dentin bonding agents. Am J Dent. 1996. 9:206–210.

22. Ferrari M, Mannocci F, Vichi A, Davidson C. Effect of two etching times on the sealing ability of Clearfil Liner Bond 2 in Class V restorations. Am J Dent. 1997. 10:66–70.

23. Miyazaki M, Ando S, Hinoura K, Onose H, Moore BK. Influence of filler addition to bonding agents on shear bond strength to bovine dentin. Dent Mater. 1995. 11:234–238.

24. Ibarra G, Vargas MA, Armstrong SR, Cobb DS. Microtensile bond strength of self-etching adhesives to ground and unground enamel. J Adhes Dent. 2002. 4:115–124.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download