Abstract

The equivalence margin is the largest difference that is clinically acceptable between the test (or experimental) drug and the active control (or reference) drug. This paper discusses the scientific principles, along with the regulatory issues, that need to be addressed when determining the equivalence margin for the biosimilar product. The concept of assay sensitivity is introduced, and the ways to ensure assay sensitivity in the equivalence trial are emphasized. A hypothetical example is presented to show how an equivalence margin is determined. The regulatory agency should carefully assess if the equivalence margin of the biosimilar product was determined using a scientifically valid and clinically relevant approach, not subject to selection bias. This is important because the consumer risk of erroneously declaring equivalence when in fact it is not must be controlled conservatively low in the approval of any biosimilar products.

Figures and Tables

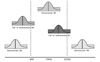

| Figure 1Assessment of bioequivalence of the generic product (T) against the reference product (R). Bioequivalence is declared if the two one sided 90% confidence interval of the geometric mean ratio (T/R) falls entirely within the range of [0.8, 1.25]. BE and BIE represent bioequivalence and bioinequivalence, respectively. Adapted from Lawrence X. Yu, PhD., Deputy Director for Science and Chemistry, Office of Generic Drugs, FDA, "Approaches to Demonstrate Bioequivalence of Narrow Therapeutic Index Drugs", Advisory Committee for Pharmaceutical Science and Clinical Pharmacology July 26, 2011. |

| Figure 2Assessment of equivalence of the biosimilar product (T) against the reference product (R) using the equivalence margin of [ML, MU]. Equivalence is declared if the confidence interval of the comparative index falls completely within the equivalence margin. |

| Figure 3Forrest plot of the differences in the proportions of patients meeting the response criteria between the reference product and placebo (hypothetical data). 'Events' denotes the number of patients who met the response criteria in each treatment group. 'RD' represents risk difference, where risk means meeting the response criteria. 'W' is relative weight used to combine the results of different studies to determine the pooled estimate. |

References

1. McCamish M, Woollett G. The state of the art in the development of biosimilars. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012. 91(3):405–417.

2. Mellstedt H, Niederwieser D, Ludwig H. The challenge of biosimilars. Ann Oncol. 2008. 19(3):411–419.

3. Njue C. Statistical considerations for confirmatory clinical trials for similar biotherapeutic products. Biologicals. 2011. 39(5):266–269.

4. Korea Food & Drug Administration. National Institute of Food and Drug Safety Evaluation. Guidelines on the Evaluation of Biosimilar Products. 2009. Seoul (Korea):

5. World Health Organization. Guidelines on evaluation of similar biotherapeutic products (SBPs). 2012.

6. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER). Guidance for industry: Scientific considerations in demonstrating biosimilarity to a reference product (Draft). 2012.

7. European Medicines Agency. Guideline on similar biological medicinal products containing monoclonal antibodies (EMA/CHMP/BMWP/403543/2010). last visited on Feb 13 2012. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2010/11/WC500099361.pdf. 10/2010, 2010. [Online].

8. Food and Drug Administration. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER). Guidance for Industry: Non-inferiority clinical trials (Draft). 2010. 03.

9. Greene CJ, Morland LA, Durkalski VL, Frueh BC. Noninferiority and equivalence designs: issues and implications for mental health research. J Trauma Stress. 2008. 21(5):433–439.

10. Hwang IK, Morikawa T. Design Issues in Noninferiority/Equivalence Trials. Drug Inf J. 1999. 33(4):1205–1218.

11. United States Government Accountability Office. New drug approval: FDA's consideration of evidence from certain clinical trials. 2010. Washington, DC, USA: United States Government Accountability Office.

12. Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Guideline on the Choice of the Non-inferiority margin. EMEA/CPMP/EWP/2158/99. 2005. 07. 27. London (UK):

13. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Spiegelhalter DJ. A re-evaluation of random-effects meta-analysis. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc. 2009. 172(1):137–159.

14. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986. 7(3):177–188.

15. The Cochrane Collaboration. Higgins J, Green S, editors. 9.5.4 Incorporating heterogeneity into random-effects models. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 5.1.0. 2011. [updated March 2011].

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download