Abstract

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) is a rare disorder that is associated with hypertensive crises. In this article, we present a 59-year-old male patient with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) caused by an acute hypertensive crisis after entering a steam bath in alcohol intoxicated status. In our case, oxidative stress resulting from alcohol metabolism may have lead to blood brain barrier (BBB) breakdown, serving as an aggravating factor in PRES. Thus we must always consider the possibility of PRES when treating chronic alcoholic patients with abnormal neurologic symptoms.

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) was initially described by Hinchey et al in 1996.1 PRES is a diagnosis based on a characteristic clinical and radiographic pattern in the setting of a predisposing factor. The clinical presentation is characterized by several reversible symptoms such as headache, altered mental status, seizures and visual disturbance. The typical neuroimaging findings of PRES are symmetric hyper-intensities on magnetic resonance FLAIR images due to vasogenic edema classically in the occipital and parietal regions.2 Various co-morbidities and drugs have been suggested as triggering factors. We report on the case of 59-year-old man with chronic alcoholism, who suddenly developed PRES caused by an acute hypertensive crisis after entering a steam bath in drunken status as a triggering event.

A 59-year-old man with a history of chronic alcoholic who drank half a bottle of Soju (korean distilled spirits) per day for the last 35 years was admitted to the emergency room for behavioral change. He went to a public sauna in drunken status 4 days before hospital admission. After a few hours in the sauna, he suddenly went out naked in public, and a clerk helped him into his clothes and led him outside. He did not return home for 3 days and the police brought him home. His family took him to the hospital the next day for his abnormal behavior. He failed to grasp nearby objects due to visual disturbances, and also presented with gait disturbance, cognitive impairment and aphasia. At the time of presentation, the patient was apyretic, with a blood pressure of 191/100 mmHg and heart rate of 52 beat/min. He was never diagnosed with any other medical conditions, including hypertension. His initial laboratory analysis showed no specific abnormalities except for macrocytosis (MCV : 96.2 10-6 m3), low platelet count (101 × 103) and a slightly elevated ammonia level (36µmol/L). Vitamin B12, vitamin B1 dosage and transketolase activity studies were not performed. Brain CT scan on admission showed an old infarction at the right basal ganglia and abnormal low densities at bilateral occipital and parietal subcortical white matter.

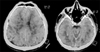

Wernicke-Korsakoff's syndrome was the initial impression, and intravenous thiamine (100 mg daily) was administered for 7 days, followed by oral thiamine (20 mg daily). The patient was evaluated with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) including diffusion weighted images. Focal lesions with high signal intensity were noted at the right basal ganglia on T2-weighted images from an old infarction. Increased signal intensities were also noted in the subcortical white matter of bilateral parietal and occipital lobes on T2-weighted and diffusion-weighted images (Fig. 1). The radiological pattern was compatible with PRES. This finding prompted doctors to reconsider their first impression, and the diagnosis of PRES was made for which the patient was admitted to the neurology department.

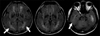

He was given 80 mg of steroid for resolution of brain edema. Blood pressure control was difficult, and intravenous Labetalol was infused on the first day followed by intravenous Nicardipine infusion for 7 days. Fourteen days after initial presentation, he was transferred in to the Department of Rehabilitation. Restless behavior suspicious of akathisia, and rapid mood changes were observed. Lab results showed normal Vitamin B12, Vitamin B1, and Folate levels. Brain positron emission tomography scan done 1 month after onset showed decreased metabolic function in the portion where brain edema had formerly existed (Fig. 2). Visual Evoked Potential showed prolonged P100 latency at both sides and torched P1 waves (Table 1). We treated the patient with 120 mg of Propranolol for his akathisia, 5 mg of escitalopram for mood changes, and 10 mg of donepezil with 2 combination tablets of levodopa 50 mg/carbidopa 12.5 mg/entacapone 200 mg to improve his cognitive function. We also tapered out oral prednisolone. After 1 month of treatment, the patient showed improvements restlessness and mood instability, but only limited improvements in cognitive function and verbal output. Visual improvement had improved to an extent where he could grasp near objects. Follow-up T2-weighted axial MRI 2 months later revealed that the previously recognized T2 high-signal lesions had resolved only slight (Fig. 3).

PRES is usually associated with several conditions including hypertension, renal disease, eclampsia, infections, immunosuppression status, transplantation, collagen vascular disorders like systemic lupus erythematosus and use of several cytotoxic drugs such as cyclosporine and tacrolimus.3 Recently, PRES has also been mentioned in association with alcoholism. To date, only two cases of PRES associated with chronic alcoholism have been documented.4,5 In those previous reports, and also in our case, all patients were chronic alcoholics without previous history of hypertension. Compared with the previous reports, one of the characteristics of this case was that the patient showed high blood pressure at time of admission despite lack of hypertensive history. It is likely that there is a close temporal relation between development of neurological symptoms and entering a steam bath in drunken status as a triggering event.

The exact mechanism of PRES is not clear and remains controversial and seems to be multifactorial. However, it is known that the biologic basis for PRES is likely an insult to cerebrovascular autoregulation. It may result from specific substances that induce focal breakdown of the BBB endothelium with fluid shifts from the intravascular to the extravascular compartment.2 In this case, alcohol-induced oxidative stress in brain endothelial cells may have caused blood-brain barrier dysfunction. PRES may also result from a sudden and severe hypertension that overwhelmes the brain's normal autoregulation of cerebral blood flow. This may lead to acute disruption of the blood-brain barrier like dilatation of cerebral arterioles secondary to capillary leakage and subsequent vasogenic edema. Until now it is not known whether increased blood pressure is a cause or a consequence of the disrupted BBB and the consecutive cerebral vasogenic edema.

Alcohol exposure increases the levels of reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide in brain endothelial cells. Oxidative stress resulting from alcohol metabolism can especially lead to BBB breakdown, serving as an aggravating factor in PRES. Moreover, the catabolic rate of alcohol increases in high temperature environments such as a steam bath. In this case, a rapidly increased level of alcohol metabolites induced by steam bathing in drunken status may have evoked an acute vascular endothelium dysfunction and led to cerebral vasogenic edema, in particular at the posterior cerebral artery. The selective involvement of parts of the brain perfused by the posterior circulation and the rapid reversibility of symptoms indicates a loss of autoregulation of the vertebrobasilar system, likely due to its relatively sparse sympathetic innervation. Gharabawy et al.6 stated that cerebral white matter is preferentially involved in PRES, probably because it is composed of myelinated-fiber tracts in a cellular matrix of glial cells, arterioles, and capillaries, which renders this region more at risk for vasogenic edema.

PRES is usually managed with supportive care such as control of hypertension, correction of electrolyte imbalance, and management of seizures. Treatment of hypertension is likely to play a significant role in reversibility of posterior reversible encephalopathy. If hypertension is present, the mean arterial pressure should only be reduced by 20 to 25% within the first 1 to 2 hrs.7 For hypertensive emergency, intravenous nicardipine, labetolol or hydralazine can be given as a bolus and both have an onset of action of less than 15 min.8 However, there are no definite treatment guidelines for the use of steroids, even though we used steroids in this case for symptomatic relief and observed recovery. PRES is known to be associated with vasogenic edema, and the use of steroids for this purpose may be relevant.2,7 With appropriate treatment, PRES is usually reversible. However, permanent neurologic disability and death from progressive cerebral edema and intracranial hemorrhages have been reported, and the possibility of irreversibility should be considered.1 In this case, cognitive impairment and abnormal signal changes in brain MRI had lasted for longer than two months since the onset of the disease. Usually, PRES is reversible with appropriate treatment and rapid correction of the cause. The temporal delay between symptom onset and hospitalization maybe the major cause of incomplete recovery in this case.

We presented a case of PRES in a chronic alcoholism patient who had visual impairment and acute psychiatric symptoms. PRES should be considered when making a diagnosis for disturbed consciousness in alcoholic patients. PRES is a diagnosis based on a characteristic clinical and radiographic pattern in the setting of a predisposing factor. In this case, we considered Wernicke's encephalopathy and hepatic encephalopathy in the differential diagnosis. This might be the first case that reports PRES related with alcoholism in Korea. We must bear in mind that great caution is needed when treating chronic alcoholic patients with abnormal neurologic symptom.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Magnetic resonance imaging in PRES. T2 weighted axial MRI images on admission (A) Diffusion weighted axial MRI on admission (B), shows increased signal intensities in the subcortical white matter of bilateral parietal and occipital lobes.

Fig. 2

Positron Emission Tomography (PET) brain scan axial images done 30 days after onset shows decreased glucose uptake in bilateral parietal and occipital lobes.

References

1. Hinchey J, Chaves C, Appignani B, Breen J, Pao L, Wang A. A reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1996; 334:494–500.

2. Bartynski WS. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, part 1: fundamental imaging and clinical features. Am J Neuroradiol. 2008; 29:1036–1042.

3. Lee VH, Eelco FM, Manno EM, Rabinstein AA. Clinical spectrum of reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome. Arch Neurol. 2008; 65:205–210.

4. Kimura R, Yanagida M, Kugo A, Taguchi S, Matsunaga H. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in chronic alcoholism with acute psychiatric symptoms. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010; 32:447.

5. Bhagavati S, Choi J. Atypical cases of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: clinical and MRI features. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008; 26:564–566.

6. Gharabawy R, Pothula VR, Rubinshteyn V, Silverberg M, Gave AA. Epinephrine-induced posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: a case report. J Clin Anesth. 2011; 23:505–507.

7. Stott VL, Hurrell MA, Anderson TJ. Reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome: a misnomer reviewed. Intern Med J. 2005; 35:83–90.

8. Finsterer J, Schlager T, Kopsa W, Wild E. Nitroglycerin-aggravated preeclamptic posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES). Neurology. 2003; 61:715–716.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download