Abstract

West Nile virus (WNV) is the most widespread arbovirus in the world. It can cause serious or fatal central nervous system (CNS) infection. We present a case of 58-year-old man who developed neuropsychologic and psychiatric impairment such as cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, health concerns and thought disorder after West Nile virus encephalitis. This is the first imported case of West Nile virus infection in Korean.

West Nile virus is found throughout Africa and the Middle East and in parts of Europe, Russia, India, and Indonesia. The virus was widely known when there was the outbreak of West Nile infection in New York City in 1999 and since then, West Nile virus progressively has extended its range.1 Although most West Nile virus infections are asymptomatic, but up to 20% of patients develop a flulike illness called West Nile fever and up to 1% of patients develop neuroinvasive disease such as meningitis, encephalitis.2 Manifestations have been reported including fever, headache, nausea, vomiting, altered level of consciousness, lethargy, nuchal rigidity, tremors, myoclonus, features of parkinsonism and behavioral or personality changes. We experienced the first case of neuropsychologic and psychiatric impairment after West Nile virus encephalitis which is imported in Korea.

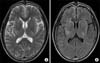

A 58-year-old man was admitted to the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine on August 27th, 2012. He was an ordinary office worker after he graduated from college, and he visited Ghana for business purposes. During his stay in Ghana, he developed a headache in the month of May 2012. He took some medication, but his headache worsened. He returned to Korea on June 28th, 2012, and was admitted to the Neurology Department of a general hospital on June 29th, 2012. He presented with headache, mild weakness, sensory changes in 4 extremities, gait disturbance, and urinary symptoms such as frequency and urgency. He was suspected of having encephalitis and MRI findings were consistent with encephalitis, demonstrating multifocal patchy T2 high signal lesions in both the basal ganglia, posterior limb of the internal capsule, and temporoparietal areas (Fig. 1). West Nile virus-specific IgG ELISA titer was elevated to 16. He was diagnosed as having West Nile encephalitis and was treated with intravenous interferon-α. Then, he was admitted to the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine of our hospital because of weakness in 4 extremities, gait disturbance, and cognitive rehabilitation. The neurologic examination was performed at the time of admission. He was alert and conscious. Manual muscle test based on the Medical Research Council grade of all extremities were grade 4. The sensory examination of all extremities was normal. He was able to walk indoors for about 50 m under supervision due to balance problem and decreased endurance. He scored 49 points on the Berg Balance Scale. Initial Functional Independence Measure (FIM) score was 94. He could perform activities of daily living, such as eating, grooming, dressing, toileting under supervision, but he needed moderate assistance with bathing.

His headache had been treated with phenytoin 400 mg, gabapentin 300 mg, pregabalin 600 mg, tramadol 50 mg, ultracet (acetaminophen 325 mg, tramadol 37.5 mg), fentanyl patch 25 mcg/h, amitriptyline 10 mg, quetiapine fumarate 25 mg, mirtazapine 7.5 mg, and escitalopram 5 mg, but the visual analogue scale (VAS: 0~10) score for his headache was 10 points. We reduced the dose of phenytoin to 200 mg and that of pregabalin to 300 mg, and stopped giving gabapentin, tramadol, ultracet, fentanyl patch, amitriptyline, and mirtazapine. We increased the dose of quetiapine fumarate to 100 mg for sleep control and that of escitalopram to 10 mg for treating the depressive mood. When he complained of exacerbation of the headache, we gave him a placebo injection, which was effective in reducing the headache immediately. After the headache was improved to a VAS score of 2 points, he started complaining that there were worms in his left ear. He also complained of both nipple pain and the source of the pain came out though his mouth and converted into the green gas. He had no previous psychiatric history. We conducted some psychological assessments to assess his thoughts and emotions on October 25th, 2012 (Table 2). Beck's Depression Inventory, reflecting the recent depression status, revealed 'minimal depression'. Depression, hypochondriasis, and schizophrenia scale scores were clinically found to be significantly elevated on the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory II. However, on face-to-face projective tests such as Rorschach-Test and House-Tree-Person (HTP) drawing test, he was found to be uncooperative; therefore, we could not confirm the possibility of thought disorder. During the interviews, he talked about the gas and the worms; hence, we suspected that he had somatic delusions. We performed the Seoul neuropsychological screening battery8 to assess multiple aspects of cognitive function on September 6th, 2012 (Table 1). The results showed impaired performance in language and related functions such as repetition, calculation, attention, visuospatial function, short-term and long-term auditory memory, retrieval of visual memory, and frontal executive functions. But generally, there was a limitation to the test because of poor patient cooperation.

He refused cognitive rehabilitation for improving the memory and attention. He also refused to undergo psychiatric treatment and medications. His delusions were limited to the somatic complaints and they did not influence his daily living; therefore, we observed his symptoms. After 2 months of comprehensive rehabilitation therapy including muscle strengthening exercises, dynamic standing balance training, and gait training, he was discharged in such a condition that he could walk independently outdoors and perform activities of daily living independently. At the time of discharge, the FIM score was 118. At the 3-month follow-up after the discharge, his somatic delusions were sustained without significant interval change. At the 1-year follow-up after the discharge, on October 8th, 2013, we conducted the Seoul neuropsychological screening battery8 and face-to-face projective test. The Seoul neuropsychological screening battery showed abnormalities in calculation, which is a language-related function, attention, visuospatial function, short-term and long-term auditory memory, and retrieval of visual memory without significant interval change (Table 1). But, he showed improvement in some of the language-related functions such as repetition, calculation, body part identification, short-term and long-term auditory memory, and frontal executive functions. The patient refused to take the Controlled Oral Word Association Test and Korean version of the Color Word Stroop Test; hence, there was a limitation in interpreting the results of frontal executive function tests. Korean Mini-Mental State Examination showed improvement in time and place orientation and language function. On face-to-face projective tests such as Rorschach-Test and HTP, the patient did not show any signs of thought disorder or perceptual disturbance and he no longer complained about the worms and the gas. But he repeatedly showed simple responses, which implied poor and unsophisticated ability to think and judge. He had persistent cognitive impairment in some of the language functions, attention, visuospatial function and memory.

The patients with West Nile virus infection experience significant long-term morbidities, such as pain, weakness, headache, and balance problem.2,3,4,5,6,7,9 The patient whom we have described in this report had weakness and balance problem, but these symptoms improved after comprehensive rehabilitation therapy. Neuropsychological and psychiatric impairment more profoundly affected his return to the society than the other problems. He showed mild to moderate impairment in multiple domains of the neuropsychological test. MRI findings showed multifocal lesions in both the basal ganglia and internal capsule, which has a critical role in frontally-mediated neurobehavioral domains such as executive function, comportment, and motivation.10 This may result in neurobehavioral impairments. After one year, the follow-up test showed improvement in some of the language-related functions, memory and frontal executive functions, but it still showed impairment in some of the language functions, attention, visuospatial function and memory.

There are few studies that used objective measures of neuropsychological functions in West Nile virus infection.2,3 Carson and Konewko et al.2 performed standardized neuropsychological tests of physical and emotional functioning in patients with West Nile virus infection. Immediate visual memory impairments and mild-to-moderate executive function impairments were reported. Sadek and Pergam et al.3 found that among the patients with West Nile neuroinvasive disease, more than half had objective neuropsychological impairment in at least two cognitive domains. David and Alan et al.10 evaluated 17 patients with West Nile virus infection. Although elemental neurologic impairments generally were mild, executive dysfunction and neuropsychiatric symptoms (particularly impulsivity and anxiety) were more severe. Also, the severity of cognitive impairments was related strongly to the rating on the FIM scale at the time of discharge from acute rehabilitation. Murray and Resnick et al.6 evaluated depression after infection with West Nile virus. About half of the patients were classified as having major depression, and mild-to-moderate depression was common.

Overall, the neuropsychiatric and psychiatric sequelae of West Nile virus infection include executive dysfunction, cognitive impairments, personality and behavioral abnormalities with varying degrees of severity. West Nile virus infection has a tendency to affect the basal ganglia, thalamus, and brainstem, which are related neurobehavioral domains than the cortical gray matter. In our case, the patient had the above mentioned symptoms to a mild degree. The difference was his somatic delusions, which were not enough to interfere with activities of daily living. A recent study found that symptoms after West Nile virus infection include fatigue and depression, and the overall mental and physical functioning returned to normal within one year of initial infection.10 In our case, the patient had persistent cognitive impairment in some of the language functions, attention, visuospatial function and memory until a year later.

We report our experience of a patient who presented with neuropsychological impairment in multiple domains, depressive symptoms, health concerns, and thought disorder after West Nile encephalitis for the first time in Korea. Attention should be paid to the neuropsychological and psychiatric impairment after West Nile virus encephalitis.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

T2 weighted magnetic resonance imaging showed multifocal patchy high signal lesions in both basal ganglia, internal capsule posterior limb, and corona radiata (A). FLAIR images reveals high signal change along the gyrus (B).

References

1. Azad H, Thomas S. West Nile encephalitis. Hosp Physician. 2004; 40:12–16.

2. Carson PJ, Konewko P, Wold KS, Mariani P, Goli S, Bergloff P, Crosby RD. Long-Term Clinical and Neuropsychological Outcomes of West Nile Virus Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2006; 43:723–730.

3. Sadek JR, Pergam SA, Harrington JA, Echevarria LA, Davis LE, Goade D, Harnar J, Nofchissey RA, Sewell CM, Ettestad P, Haaland KY. Persistant neuropsychological impairment associated with West Nile virus infection. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2010; 32:81–87.

4. Arciniegas D, Anderson C. Viral encephalitis: Neuropsychiatric and neurobehavioral aspects. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2004; 6:372–379.

5. Aslan M, Kocazeybek B, Turan N, Karakose AR, Altan E, Yuksel P, Saribas S, Cakan H, Caliskan R, Torun MM, Balcioglu I, Alpay N, Yilmaz H. Investigation of schizophrenic patients from Istanbul, Turkey for the presence of West Nile virus. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012; 262:173–177.

6. Murray KO, Resnick M, Miller V. Depression after infection with West Nile virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007; 13:479–481.

8. Kang Y, Na D. Seoul Neuropsychological Screening Battery (SNSB). Seoul: Human Brain Research & Consulting Co;2003.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download