Abstract

Reduplicative paramnesia (RP) is one of delusional disorders characterized by false belief that a familiar place, person, or object had been duplicated. There have been several hypotheses about anatomical basis of RP, and right hemispheric pathology combined with or without diffuse bifrontal pathology is commonly accepted. We report a 74-year-old man who developed reduplication of place and person after right frontoparietal cerebral infarction. On the neuropsychological examination, the patient showed marked deficit in several parts of cognition including attention, memory and execution. In accordance with the literature, our clinical report suggests that RP is associated with right parietal and frontal lesion which causes deficits of visuospatial attention, memory and integration, and also emotional confusion during hospitalization.

Delusions are pathologic beliefs that remain fixed despite clear evidence that they are incorrect. Content-specific delusions predominate in neurologic patients, usually misidentification and reduplication syndromes, with beliefs that places (reduplicative paramnesia), people (Capgras syndrome, Fregoli syndrome), or events are transformed or duplicated.1 Reduplicative paramnesia (RP) was named by Pick in 1903 to describe specific disturbance in memory characterized by subjective certainty that a familiar place, person, object or body part had been duplicated.2 RP is not a rare syndrome and its prevalence is estimated to be up to 7.8% in patients with neurological disorders.3 It is most commonly seen in patients with traumatic brain injury, and it has been also reported in many other neurologic conditions, such as stroke, brain tumor, dementia, encephalopathy and various psychiatric conditions.4 The most commonly suggested neuroanatomical location of RP is the right hemispheric pathology combined with or without diffuse bifrontallesion. However, exact pathomechanism and neural substrate are still inconclusive. Also development of classical RP after cerebral infarction is rare. We report a casethat showed RP after right frontoparietal infarction and discussed underlying pathomechanisms.

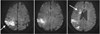

A 74-year-old, right-handed man, with 12 years of formal education, was admitted to the department of neurology due to sudden onset of left side weakness. He had been suffered diabetes mellitus for 10 years, and had lung surgery 6 months ago due to non-small cell lung cancer. He had no prior history of neurological or psychiatric illness and drug or alcohol abuse. Brain magnetic resonance (MR) diffusion weighted image showed evidence of acute cerebral infarction in right frontoparietal, right anterior corona radiata, right caudate head, and right upper basal ganglia representing right middle cerebral artery territory infarction (Fig. 1).

After 2 weeks of acute management, he was transferred to the department of physical medicine and rehabilitation for comprehensive rehabilitation programs. At the time of transfer, neurologic examination showed left side motor weakness and the grade of manual muscle testing was 3/5 in upper and lower extremities. There was no abnormality in the cranial nerve examination and the visual field was intact. He was able to perform activities of daily living, such as dressing, hygiene, and eating almost independently, and could walk with some assist.

Cognitive function was evaluated by Korean-Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) and domain specific neuropsychological tests using computerized neurocognitive function test (Max Medica, Seoul, Korea) and Rey-O-Complex Figure Test (Table 1) on the 2nd day after transfer in. The K-MMSE score was 24 out of 30 points, and he was disoriented in 'time'. In attention and working memory tests, he showed a marked impairment. In verbal and nonverbal memory tests, he also showed a marked impairment, but exhibited a slightly better performance of verbal memory than nonverbal memory tests. A marked impairment was also demonstrated in the executive function tests in stroop and Wisconsin card sorting test, and nonverbal intelligence test by Raven's Coloured Progressive Matrices. Visuoconstructive ability was also poor and additional neglect tests, which were a line bisection test and a star cancellation test, revealed left hemineglect.

On the 6th day after transfer in, he suddenly got upset and claimed that someone had built this whole hospital in his house without his permission. As the nurse who was in charge of him disbelieved his claim, he showed an aggressive behavior. He became somewhat calmed down after his attending doctor promised him for a contact with the hospital director next day. There was no preceding drug administration which could cause a delirium or delusion. Brain MR diffusion weighted image was taken immediately for a suspicion of recurrence of cerebral infarction, but there was no newly developed lesion. Medical consultation with the department of psychiatry was performed for a doubt of emergency psychiatric illness. The psychiatrist considered his symptom as a delirium caused by general medical condition. A few days later, when questioned as to where he was, he was correctly oriented in "Seoul, Korea University Anam Hospital, seventh floor". However, he insisted that "Korea University Anam Hospital" was in his room at his house. When pressed about how the entire hospital can be in his room, he didn't know the reason, but was able to describe well about the hospital bed and other facilities like a curtain and a toilet which were in his hospital room. During the admission period, he often deluded his doctor into a familiar relative, which could be explained as another RP about person. He had no other behavioral problem except delusions about 'person' and 'place'.

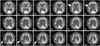

His delusions seemed to be continued after he went home on leave and got back to the hospital during his hospitalization period. As the disruption of sleep-wake cycle was accompanied with RP, we started pharmacologic intervention with 25 mg/day of trazodone before bedtime, and it seemed to help him to lessen sleep disturbance, but there was no promising effect for RP. Tc-99m-ECD SPECT was performed at 1 week after the onset of RP to assess brain metabolism, and it revealed markedly decreased perfusion in the right basal ganglia and posterior parietooccipital region (Fig. 2). After 4 weeks of rehabilitation program, he became to perform activities of daily living and walk independently. He still believed that the hospital was in his house, but anyway the impulsiveness of thought was disappeared, and discharged from hospital. Two months after the onset of cerebral infarction, when he came to our outpatient clinic, the K-MMSE score was improved to 26 out of 30 points, but we still could find the existence of RP. However, the extent of RP had seemed to be much diminished, as he was not tend to tell about his false belief, unless someone asked in detail. One year after the onset, on the interview over the phone, he stated that he no longer believed that the hospital was in his house, and he also indicated that his misconception might have resulted from initial confusion about being sick.

RP is a content-specific delusion characterized by a duplication of familiar place, person or event, and is infrequently reported when the right hemispheric or other diffuse brain lesion exists. Some authors have proposed that right posterior cerebral pathology causing disorientation for place should be essential for production of RP, and also right frontal pathology is necessary condition.5,6 Others suggested another neuroanatomical basis of RP, an acute right hemispheric lesion which was superimposed on diffuse or bifrontal deficit.7,8 Budson et al.9 have pointed out that a lesion in the ventral visual stream, which disrupting communication between the visual cortex and both visual processing areas in the inferior temporal lobe and visual memory in the nondominant parahippocampal region can produce RP. Our case had right frontoparietal lesion without diffuse bifrontal pathology or visual problem, so that, this case is the one adding sufficient evidences on the neuroanatomical hypothesis of RP after right frontal and parietal pathology.

Neuropsychological test of our patient indicated deficits in many fields of cognition: attention, memory, frontal executive function, and visuoconstructional ability. At the neuropsychological level, our findings are in general accord with the hypotheses offered by Kapur et al.,5 and Hakim et al.7 The former insisted that the combination of impairment of memory, attentional/spatial deficits and conceptual integration should be necessary for RP to occur, while the latter proposed that the right hemispheric dysfunction alter spatial coding of the environment, and the frontal dysfunction prevent recognition of this alteration. Ruff and Volpe6 once reported that in addition to visuospatial perception and memory deficit, confusion soon after admission and a strong desire to be at home might be crucial factors for producing RP. Actually, on the interview after the complete resolution of RP, our patient stated that he might have been in confusion during the admission period.

During the rehabilitation of brain injury patients, various neurobehavioral symptoms may prevent active participation of rehabilitative programs and could lead to negative consequences on functional outcomes. Classical RP is rare after cerebral infarction and inexperienced physiatrist may misrecognize RP for delirium or another psychotic disorder. This misperception may lead to excessive and long-term use of antipsychotic drugs or sedatives, and resultant negative influences on recovery from stroke. Most reports described the pathophysiology of RP, but few mentioned the clinical course and treatment. Only one report by Yamada et al.,10 stated that antipsychotics might be beneficial for resolution of RP. In our case, small dose of trazodone relieved sleep disturbance and improved his mood and motivation. And RP had lessened with the lapse of time and spontaneously disappeared. Therefore proper diagnosis of infrequent behavioral symptoms like RP may help planning rehabilitation programs and medication uses.

In conclusion, we suggest that RP is associated with right parietal and frontal lesion combined with deficits of visuospatial attention, memory and integrative functions. Although the clinical course of RP may vary according to the mechanism and location of brain injury, long-term observation of our case with right frontoparietal infarction demonstrated spontaneous recovery as time goes by.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Brain diffusion MRI at the onset of cerebral infarction showed high signal intensity in diffusion weighted image in right frontoparietal, right anterior corona radiata, right caudate head, and right upper basal ganglia, which indicated acute infarction (arrows). |

References

1. Devinsky O. Delusional misidentifications and duplications: right brain lesions, left brain delusions. Neurology. 2009. 72:80–87.

2. Pick A. Clinical studies: III. On reduplicative paramnesia. Brain. 1903. 26:260–267.

3. Murai T, Toichi M, Sengoku A, Miyoshi K, Morimune S. Reduplicative paramnesia in patients with focal brain damage. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol. 1997. 10:190–196.

4. Forstl H, Almeida OP, Owen AM, Burns A, Howard R. Psychiatric, neurological and medical aspects of misidentification syndromes: a review of 260 cases. Psychol Med. 1991. 21:905–910.

5. Kapur N, Turner A, King C. Reduplicative paramnesia: possible anatomical and neuropsychological mechanisms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1988. 51:579–581.

6. Ruff RL, Volpe BT. Environmental reduplication associated with right frontal and parietal lobe injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1981. 44:382–386.

7. Hakim H, Verma NP, Greiffenstein MF. Pathogenesis of reduplicative paramnesia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1988. 51:839–841.

8. Pisani A, Marra C, Silveri MC. Anatomical and psychological mechanism of reduplicative misidentification syndromes. Neurol Sci. 2000. 21:324–328.

9. Budson AE, Roth HL, Rentz DM, Ronthal M. Disruption of the ventral visual stream in a case of reduplicative paramnesia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000. 911:447–452.

10. Yamada M, Murai T, Ohigashi Y. Postoperative reduplicative paramnesia in a patient with a right frontotemporal lesion. Psychogeriatrics. 2003. 3:127–131.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download