Abstract

Isolated rupture of distal semitendinosus is reported rarely. Here, we report a case of 51-year-old previous healthy working man diagnosed with isolated semitendinosus tendon rupture treated successfully by conservative management.

Hamstring strains are common. They are usually treated by conservative managements with good results. Surgical treatments have been advocated in cases of complete rupture of the proximal and distal attachments1,2).

Although rare, distal ruptures of isolated semitendinosus tendon have been reported previously3-6). However, all of these previous reports were based on professional young athletes whom mostly resulted from competitive sports activity. Here, we report a case of 51-year-old previous healthy working man diagnosed with isolated semitendinosus tendon rupture treated successfully by conservative management. The patient was informed that data concerning the case would be submitted for publication, and he consented.

A 51-year-old previous healthy working man presented with popliteal area pain. Although he was active, he was not a professional sports player. The pain presented for 1 week. He claimed that the shooting-nature pain developed in medial aspect of popliteal area during stair climbing in knee extension position.

On physical examination, there was a palpable gap along the distal medial hamstring tendons that was accentuated on knee flexion. There was tenderness on palpation along the medial side of the popliteal fossa, which was exacerbated by resisted knee flexion. A full range of knee movement was maintained, and there was no medial joint laxity on valgus straining at 0 and 30 degrees of flexion.

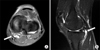

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the knee was performed. MRI examinations were performed on a 1.5 Tesla MR scanners (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI, USA) using a phased array knee coil. The MR protocol included coronal, sagittal and axial images. On coronal spin echo proton density images, the parameters were as followings: TR/TE (3000/41.8), a slice thickness of 3.5 mm, a 4-mm interslice gap, 2 NEX, field of view 16×16 cm, and a matrix of 512×256. On T2 weighed fat saturated images, the parameters were as followings: TR/TE (4000/90.9), a slice thickness of 3.5 mm, a 4-mm interslice gap, 3 NEX, field of view 16×16 cm, and a matrix of 416×256. MRI demonstrated edema, semitendinosus tendon retraction and decreased muscle volume on axial images (Fig. 1).

A nonoperative management with rest, ice, compression, and immobilization was initiated. Crutches were used as needed until independent. This was followed by focused physical therapy to maintain the strength and conditioning of the hamstrings. Strength training was always with isotonic resistance. Treatment modality progressed from walking, fast walking, jogging, and running over a 6-week period. The patient was able to climb stairs stepwise 6 weeks without difficulty.

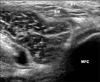

Sonography performed 12 months post-injury showed that the ruptured tendon had retracted and was tethered to the underlying semimembranosus muscle belly (Fig. 2). Hamstring muscle strength was estimated by Cybex examination which consisted of measuring the hamstring peak torque at two speeds: 60°/s and 180°/s. Relative strength reached 85% compared to the contralateral limb. The initial Lysholm score7) of 58 improved to 95 at latest follow-up.

There have been a few case reports in the English literature regarding the isolated distal semitendinosus tendon rupture5,6). Recently, Cooper and Conway4) reported the retrospective case series with the results of treatment in professional athletes. However, this is the first report of isolated distal semitendinosus tendon rupture developed in non-athlete ordinary office-working man with injury developed during daily activity.

Because of the rarity, there is paucity of evidence over the best method of managing the injury; whether surgical or non-surgical. Cooper and Conway4) reported 42% (5/12) of failure when managed initially by nonoperative treatment. However, the failure of non-operative treatment in their study was defined by one of the following: no substantial improvement in hamstring muscle weakness or pain over a 6-week period, intractable pain on sprinting, or persistence of scarring in the distal medial thigh that did not improve with soft tissue rehabilitation techniques. This strict definition may not be necessary to non-athletic people. In contrary to the mentioned article, Sekhon and Anderson5) described 2 cases that a professional National Football League player returned to competition 2 weeks after injury with infiltration of a local anesthetic for pain control and a professional baseball player who resumed competition after 4 weeks of rehabilitation alone. They suggested that in given time, athletes do make a complete recovery without the need for surgical repair.

The exact mechanism of isolated semitendinosus tendon injury is not known. Schilders et al.6) in their case report, they described, "The injury had been sustained whilst lunging for the ball with an outstretched leg: which had sustained an impact; with eccentric loading of the hamstrings." Adejuwon et al.3) in their report described, "While performing sprint-start drills…" and "During a 100-m preliminary round…" Therefore, it is mentioned that most athletic players give a history of feeling sharp, searing, acute pain during sprinting or on extended stride4). The patient in our case also had sudden-onset shooting nature pain during knee extension position, although not in a highly-demanding strenuous activity. Without any underlying disease, we were surprised that this disease entity could not only be found in professional sports player but also in ordinary people with daily living activities such as a stair climbing.

When patients complain of posteromedial aspect pain with tenderness, such disease entity should be kept in mind. Because unlike semiteninosus bursitis or tendinitis, focused physical therapy may be needed.

It is prone to report the outcome of our interventions, particularly after a surgical course of action, but it is also important to document the outcomes of conservative treatments of rare tendinous injury especially in patients who are not involved in professional sports activity. Conservative treatment including careful rehabilitation program can be successful in the management of isolated semiteninosus tendon rupture.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Orava S, Kujala UM. Rupture of the ischial origin of the hamstring muscles. Am J Sports Med. 1995. 23:702–705.

2. Sallay PI, Friedman RL, Coogan PG, Garrett WE. Hamstring muscle injuries among water skiers. Functional outcome and prevention. Am J Sports Med. 1996. 24:130–136.

3. Adejuwon A, McCourt P, Hamilton B, Haddad F. Distal semitendinosus tendon rupture: is there any benefit of surgical intervention? Clin J Sport Med. 2009. 19:502–504.

4. Cooper DE, Conway JE. Distal semitendinosus ruptures in elite-level athletes: low success rates of nonoperative treatment. Am J Sports Med. 2010. 38:1174–1178.

5. Sekhon JS, Anderson K. Rupture of the distal semitendinosus tendon: a report of two cases in professional athletes. J Knee Surg. 2007. 20:147–150.

6. Schilders E, Bismil Q, Sidhom S, Robinson P, Barwick T, Talbot C. Partial rupture of the distal semitendinosus tendon treated by tenotomy: a previously undescribed entity. Knee. 2006. 13:45–47.

7. Lysholm J, Gillquist J. Evaluation of knee ligament surgery results with special emphasis on use of a scoring scale. Am J Sports Med. 1982. 10:150–154.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download