Abstract

PURPOSE

To longitudinally assess the quality of life in maxillectomy patients rehabilitated with obturator prosthesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Thirty-six subjects were enrolled in the span of 16 months, out of which six were dropouts. Subjects (age group 20-60 years) with maxillary defects, irrespective of the cause, planned for definite obturator prosthesis, were recruited. The Hindi version of European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, Head and Neck version 1 of Quality of Life Questionnaire was used before surgical intervention and one month after definitive obturator. Questionnaire includes 35 questions related to the patient's physical health, well being, psychological status, social relation and environmental conditions. The data were processed with statistical package for social science (SPSS). Probability level of P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The quality of life after rehabilitation with obturator prosthesis was 81.48% (±13.64) on average. On item-level, maximum mean scores were obtained for items problem with teeth (1.87 ± 0.94), pain in mouth (1.80 ± 0.92), trouble in eating (1.70 ± 0.88), trouble in talking to other people (1.60 ± 1.22), problems in swallowing solid food (1.57 ± 1.22) and bothering appearance (1.53 ± 1.04); while minimum scores were obtained for the items coughing (1.17 ± 0.38), hoarseness of voice (1.17 ± 0.53), painful throat (1.13 ± 0.43), trouble in having social contacts with friends (1.10 ± 0.40) and trouble having physical contacts with family or friends (1.10 ± 0.31).

The term quality of life has have been used since Aristotle, when quality of life meant happiness. Quality of life is the degree of well-being felt by an individual. The WHO defines quality of life as the individual's perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns.1,2 It also encompasses the aspects of physical well being, personal well being, social, functional activities and economic influences.3 Earlier, end points such as recurrence rates and survival were used to evaluate the efficacy of various therapeutic measures in head and neck cancer while patient's quality of life was usually ignored. Presently, the multitudinal impact of maxillofacial tumors on a patient's life has been recognized, which led various researchers to investigate the quality of life of those patients.4 However, studies evaluating the quality of life of patients with maxillectomy defects and the effect of prosthodontic therapy with obturator prostheses on their quality of life remain rare.

The significant areas of treatment concern after maxillary resection are reconstruction of the defect and restoration of oronasal functions while maintaining the facial contours. The obturator prosthesis fulfills most of these requirements and it also reduces the procedure time and offers the possibility of immediate rehabilitation. It is possible to examine the surgical site after removing the prosthesis, and recurrence may be detected at an early stage.5-8 So, the obturator can be considered as a highly positive approach for rehabilitation after maxillectomy. However, in some cases, impaired obturator functioning and handling may lead to deficits in speech, mastication, swallowing or facial disfigurement, thereby resulting in patient dissatisfaction.5,9,10

Various investigators have found that orofacial deformities result in profound psychological and social consequences.11-13 Such subjects are more likely to encounter social negligence and usually develop negative personality traits. McGrouther11 concluded that even minor orofacial abnormalities are considered as a social taboo. Maxillofacial injury rehabilitation represents one of the greatest challenges to public health service providers worldwide because of their high incidence and significant financial burden. They are often associated with morbidity and varying degree of physical, functional and aesthetic damages.12,13

However, only a few cross-sectional studies have evaluated the change in quality of life in maxillectomy patients after obturator therapy. Hence, this study was planned to longitudinally assess the quality of life in maxillectomy patients rehabilitated with obturator prostheses. The null hypothesis of this study was that the quality of life of maxillectomy patients after obturator prosthesis is not changed.

Thirty six subjects were enrolled in the study for the span of sixteen months. Ethical approval was obtained from the institution. Prior to the participation in the study, all procedures utilized for the study were thoroughly explained to the patients, a written consent was obtained and patients were free to ask any study related questions. Patients only with maxillary defects, irrespective of the cause of the defect, otherwise healthy, planned for definite obturator prosthesis, in age group of 20-60 years were selected. Standard technique was used for obturator fabrication by the same prosthodontist who has more than eight years of clinical experience.

The instructions regarding filling of questionnaire were explained to the selected thirty six subjects, but for evaluation, only thirty subjects were available as six subjects had declined to be involved in the study. The Hindi version of European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, Head and Neck version 1 of Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-H&N 35) was used.14

The questionnaire includes 35 questions related to patient's physical health, well being, psychological status, social relation and environmental conditions. The questionnaire was divided into two parts with initial 30 multiple choice questions, with scoring based on Likert scale of four-points, which were used to quantitatively measure the patient's perceived changes in the quality of life. Remaining 5 questions were dichotomous and were used for status evaluation of the patients. Patients were asked to complete questionnaire based on their experience during the past one week before surgical intervention, the same questionnaire was completed by the patient after definitive prosthetic rehabilitation. The quality of life of subjects was broadly divided into eight dimensions as follows:

To compare the relative quality of life on different dimensions, weighted mean scores have been noted. The weighted scores were taken by dividing the total scores of a dimension by the number of items for that particular dimension. The data were processed with statistical package for social science (SPSS) version 15.0 for windows statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The pre- and post-observations were compared by paired t-test while discrete observations were compared by Chi-Square test. Quality of life scores were computed. The probability levels of P<.05 were considered statistically significant for all statistical analyses.

The social, demographic, disease and treatment characteristics of the 30 patients assessed are mentioned in Table 1.

The patient's perceived quality of life after rehabilitation with obturator was calculated to be 81.48% (± 13.64). Majority of patients belonged to age group <30 years and age group 51-60 years respectively, showing a bimodal age distribution. There were only 2 patients in age group >70 years. Mean age of patients was 46.83 ± 16.98 years.

Maximum number of subjects were illiterates (n = 12; 40%) followed by those who had completed their schooling up to Standard XII (n = 9; 30%) and those who were Graduates or above (n = 9; 30%).

The lower incidence rate combined with high mortality rate of maxillary cancer usually results in small sample sizes found in studies related to maxillectomy patients. Majority (n = 17; 56.7%) of the patients were from rural areas while remaining 13 (43.3%) belonged to urban areas. Majority of the patients were tobacco users (56.3%) consuming tobacco 6-10 times a day (58.8%). Majority of subjects (n = 16; 53.3%) belonged to Aramany's15 class I, followed by those in Class II (20%), Class VI (13.3%) and Class III (10%) respectively. There was only 1 (3.3%) subject who belonged to Class IV.

Squamous cell carcinoma was the most common clinical diagnosis (50%) responsible for maxillectomy. Surgery alone (n = 19; 63.3%) was the most common treatment modality used.

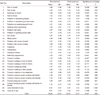

On item-level, maximum mean scores were obtained for items problem with teeth (1.87 ± 0.94), pain in mouth (1.80 ± 0.92), trouble in eating (1.70 ± 0.88), trouble in talking to other people (1.60 ± 1.22), problems in swallowing solid food (1.57 ± 1.22) and bothering appearance (1.53 ± 1.04) while minimum scores were obtained for the items coughing (1.17 ± 0.38), hoarseness (1.17 ± 0.53), painful throat (1.13 ± 0.43), trouble in having social contacts with friends (1.10 ± 0.40) and trouble having physical contacts with family or friends (1.10 ± 0.31) (Table 2).

Minimum effect on quality of life was observed for the sex related QOL whereas maximum was observed for social life. At item-level, statistically significant reduction in mean scores was found for the items such as pain in mouth (P=.032), soreness in mouth (P=.001) and coughing (P=.025) (Table 2). A statistically significant increase in mean scores was observed for items such as problems in swallowing solid food, problem in opening mouth wide, trouble in eating, difficulty in eating food in front of family and other people, problem in enjoying food, difficulty in conversation to people and on the telephone, problem in making social contacts with friends, trouble in making public appearance and difficulty in making physical contacts with others. For all the other items the change was not significant statistically (P>.05). Overall, no significant change in mean scores was observed.

Recently, after the recognition of the multitudinal impact of maxillofacial tumors on a patient's life, increased heed has been paid to research related to investigating their quality of life. The present study investigated the quality of life of patients with maxillectomy after rehabilitation with obturator prostheses. In spite of numerous researches regarding the quality of life after cancer therapy, only a few studies emphasize on the quality of life of maxillectomy patients rehabilitated with obturator.4-6,16-21

In the present study, thirty patients were investigated. Depprich et al.21 studied forty three patients, Rogers et al.22 interviewed ten patients, Hertrampf et al.17 evaluated seventeen patients, Irish et al.4 forty two patients and Kornblith et al.6 forty seven patients.

Numerous previous investigators have used the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (QLQ-C30) for assessing the health related quality of life of cancer patients.23-26 In the present study, a 35-item head and neck module (EORTC QLQ-H&N35) was utilized. This standardized questionnaire allows a comparison between multiple study groups.

The quality of life after rehabilitation with obturator prostheses was calculated to be 81.48% (± 13.64). The direct comparison of these results with the previous studies are not possible as in different studies, different tests and scales were used to evaluate the quality of life. But the results obtained from the present study are supported by the results of Depprich et al.21, Schwarz and Hinz26 and Hertrampf et al.17 Studies conducted by Irish et al.4 and Kornblith et al.27 also reported that the patients adjusted favorably after maxillectomy and rehabilitation with obturator prostheses.

In most of the previous studies, similar tothe study conducted by Depprich et al.,21 only the quality of life after prosthetic rehabilitation was evaluated by a cross-sectional study whereas in the present study, the quality of life before prosthetic rehabilitation as well as the quality of life after prosthetic rehabilitation have been assessed by a longitudinal study, thereby enabling us to simultaneously evaluate the change in the quality of life scores, which was found to be in order of significance of change as 0.665.

In the present study, age of patients ranged from 20 to 76 years. Majority of patients belonged to age group <30 years and age group 51-60 years respectively, showing a bimodal age distribution. There were only 2 patients in age group >70 years. Mean age of patients was 46.83 ± 16.98 years. For younger patients, the quality of life score was 73.02% in comparison to the score of older age group which was 87.78% after prosthetic rehabilitation. These findings correspond to the findings of Depprich et al.21 who also credited the preponderance of older patients (61% > 60 years) for the outcome of his study, considering that there exists an inverse relationship between age and psychological distress. Elderly patients, who anticipate to have age related physical illness, suffer less from distress related to cancer as compared with younger patients who feel that their life span has been shortened and their quality of life impaired due to the ailment.28

Patients suffering from maxillofacial tumors develop coping strategies and so they gain an increase of quality of life after prosthetic rehabilitation.17 Most of the patients do not criticize their decision after knowing the treatment outcome and consider that being alive outweighs the demerits of obturator therapy.

Good obturator function has been found to be responsible for improved quality of life.4,6,16,17,22 However, in the present investigation, only the quality of life of maxillectomy patients after obturator was assessed but other domains related to the obturator function and the effect of family behavior, which also contribute to the quality of life were not studied in detail.

The small sample size and selection bias introduced by a refusal rate of 12% were the limitations of the present study. However, the refusal rate in the present study was relatively low as compared with the refusal rates reported in other cancer studies such as Depprich et al.21 where refusal rate was 28%, Kornblith et al.6 28% and Irish et al.4 with refusal rate of 39%. The lower incidence rate combined with high mortality rate of maxillary cancer usually results in small sample sizes found in studies related to maxillectomy patients.

The present study found that except for change in scores for senses, general health and sex, for all the other dimensions a significant change was observed. Except for pain, for all the other dimensions where significant changes were observed, mean scores were found to be significantly increased after treatment. For pain a significant reduction in mean scores was found. For both pre-and-post-treatment evaluations, minimum scores were observed for the dimension sex whereas maximum scores were obtained for the item eating. No significant change in physical status was observed following treatment (P>.05). The reduction in pain scores as found in this study is contradictory to the previous studies done by Hertrampf et al.17 and Rogers et al.22

In the present study, at item-level, statistically significant decrease in mean scores was observed for the items pain in mouth, soreness in mouth and coughing. A statistically significant increase in mean scores was observed for items - problems in swallowing solid food, problem in opening mouth wide, trouble in eating, difficulty in eating food in front of family and other people, problem in enjoying food, difficulty in conversation to people and on the telephone, problem in making social contacts with friends, trouble in making public appearance and difficulty in making physical contacts with others. The above observations of the present study are supported by the results obtained from study conducted by Depprich et al.21, Irish et al.4 and Kornblith et al.6

In the present study, surgery alone (n = 19; 63.3%) was the most common treatment modality availed followed by surgery + radiotherapy + chemotherapy (n = 5; 16.7%), surgery + radiotherapy (n = 4; 13.3%) and surgery + chemotherapy (n = 2; 6.7%). According to the study conducted by Depprich et al.21, the most common treatment modality was surgery only.

It was found that squamous cell carcinoma was the most common clinical diagnosis (50%) followed by adenoid cystic carcinoma of hard palate (n = 4; 13.3%). Malignant melanoma (n = 3; 10%) and nasopharyngeal angiofibroma (n = 2; 6.7%) were the next most common diagnosis. Ameloblastoma, cleft lip and palate, cystic lesion, giant cell tumor, osteoclastoma and sinonasal solitary fibrous tumor were present in 1 (3.3%) case each. Depprich et al.21 also found the similar results with most common diagnosis to be Squamous cell carcinoma (52%, 16/31), followed by adenocarcinoma (19%, 6/31).

The hypothesis that the quality of life of maxillectomy patients after obturation is acceptable is justified by the results of the present study. Future research on defect related newer obturator designs may help to overcome the problems typically associated with obturator prostheses and will help to improve patient's quality of life after maxillectomy in the future.

Figures and Tables

References

1. What quality of life? The WHOQOL Group. World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment. World Health Forum. 1996. 17:354–356.

2. The World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL): position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc Sci Med. 1995. 41:1403–1409.

3. Felce D, Perry J. Quality of life: its definition and measurement. Res Dev Disabil. 1995. 16:51–74.

4. Irish J, Sandhu N, Simpson C, Wood R, Gilbert R, Gullane P, Brown D, Goldstein D, Devins G, Barker E. Quality of life in patients with maxillectomy prostheses. Head Neck. 2009. 31:813–821.

5. Borlase G. Use of obturators in rehabilitation of maxillectomy defects. Ann R Australas Coll Dent Surg. 2000. 15:75–79.

6. Kornblith AB, Zlotolow IM, Gooen J, Huryn JM, Lerner T, Strong EW, Shah JP, Spiro RH, Holland JC. Quality of life of maxillectomy patients using an obturator prosthesis. Head Neck. 1996. 18:323–334.

7. Matsuyama M, Tsukiyama Y, Tomioka M, Koyano K. Clinical assessment of chewing function of obturator prosthesis wearers by objective measurement of masticatory performance and maximum occlusal force. Int J Prosthodont. 2006. 19:253–257.

8. Depprich RA, Handschel JG, Meyer U, Meissner G. Comparison of prevalence of microorganisms on titanium and silicone/polymethyl methacrylate obturators used for rehabilitation of maxillary defects. J Prosthet Dent. 2008. 99:400–405.

9. Martin JW, King GE, Kramer DC, Rambach SC. Use of an interim obturator for definitive prosthesis fabrication. J Prosthet Dent. 1984. 51:527–528.

10. Wolfaardt JF. Modifying a surgical obturator prosthesis into an interim obturator prosthesis. A clinical report. J Prosthet Dent. 1989. 62:619–621.

11. McGrouther DA. Facial disfigurement. BMJ. 1997. 314:991.

12. Alvi A, Doherty T, Lewen G. Facial fractures and concomitant injuries in trauma patients. Laryngoscope. 2003. 113:102–106.

13. Brasileiro BF, Passeri LA. Epidemiological analysis of maxillofacial fractures in Brazil: a 5-year prospective study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006. 102:28–34.

14. Chaukar DA, Das AK, Deshpande MS, Pai PS, Pathak KA, Chaturvedi P, Kakade AC, Hawaldar RW, D'Cruz AK. Quality of life of head and neck cancer patient: validation of the European organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ-C30 and European organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ-H&N 35 in Indian patients. Indian J Cancer. 2005. 42:178–184.

15. Aramany MA. Basic principles of obturator design for partially edentulous patients. Part I: classification. J Prosthet Dent. 1978. 40:554–557.

16. Rieger JM, Wolfaardt JF, Jha N, Seikaly H. Maxillary obturators: the relationship between patient satisfaction and speech outcome. Head Neck. 2003. 25:895–903.

17. Hertrampf K, Wenz HJ, Lehmann KM, Lorenz W, Koller M. Quality of life of patients with maxillofacial defects after treatment for malignancy. Int J Prosthodont. 2004. 17:657–665.

18. Koyama S, Sasaki K, Inai T, Watanabe M. Effects of defect configuration, size, and remaining teeth on masticatory function in post-maxillectomy patients. J Oral Rehabil. 2005. 32:635–641.

19. Landes CA. Zygoma implant-supported midfacial prosthetic rehabilitation: a 4-year follow-up study including assessment of quality of life. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2005. 16:313–325.

20. Lethaus B, Lie N, de Beer F, Kessler P, de Baat C, Verdonck HW. Surgical and prosthetic reconsiderations in patients with maxillectomy. J Oral Rehabil. 2010. 37:138–142.

21. Depprich R, Naujoks C, Lind D, Ommerborn M, Meyer U, Kübler NR, Handschel J. Evaluation of the quality of life of patients with maxillofacial defects after prosthodontic therapy with obturator prostheses. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011. 40:71–79.

22. Rogers SN, Lowe D, McNally D, Brown JS, Vaughan ED. Health-related quality of life after maxillectomy: a comparison between prosthetic obturation and free flap. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003. 61:174–181.

23. Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, de Haes JC, Kasa S, Klee M, Osoba D, Razavi D, Rolfe PB, Schraub S, Sneeuw K, Sullivan M, Takeda F. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993. 85:365–376.

24. Bjordal K, de Graeff A, Fayers PM, Hammerlid E, van Pottelsberghe C, Curran D, Ahlner-Elmqvist M, Maher EJ, Meyza JW, Brédart A, Söderholm AL, Arraras JJ, Feine JS, Abendstein H, Morton RP, Pignon T, Huguenin P, Bottomly A, Kaasa S. EORTC Quality of Life Group. A 12 country field study of the EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 3.0) and the head and neck cancer specific module (EORTC QLQ-H&N35) in head and neck patients. Eur J Cancer. 2000. 36:1796–1807.

25. Fayers PM. Interpreting quality of life data: population-based reference data for the EORTC QLQ-C30. Eur J Cancer. 2001. 37:1331–1334.

26. Schwarz R, Hinz A. Reference data for the quality of life questionnaire EORTC QLQ-C30 in the general German population. Eur J Cancer. 2001. 37:1345–1351.

27. Kornblith AB, Anderson J, Cella DF, Tross S, Zuckerman E, Cherin E, Henderson E, Weiss RB, Cooper MR, Silver RT. The Cancer and Leukemia Group B. Hodgkin disease survivors at increased risk for problems in psychosocial adaptation. Cancer. 1992. 70:2214–2224.

28. Gurland B. Sadavoy J, Lazarus LW, Jarwik LF, editors. Epidemiology of psychiatric disorders. Comprehensive review of geriatric psychiatry. 1991. . Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press;25–40.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download