Abstract

PURPOSE

The purpose of this study was to investigate the diametral tensile strength of polymer-based temporary crown and fixed partial denture (FPD) materials, and the change of the diametral tensile strength with time.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

One monomethacrylate-based temporary crown and FPD material (Trim) and three dimethacrylate-based ones (Protemp 3 Garant, Temphase, Luxtemp) were investigated. 20 specimens (ø 4 mm × 6 mm) were fabricated and randomly divided into two groups (Group I: Immediately, Group II: 1 hour) according to the measurement time after completion of mixing. Universal Testing Machine was used to load the specimens at a cross-head speed of 0.5 mm/min. The data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, the multiple comparison Scheffe test and independent sample t test (α = 0.05).

RESULTS

Trim showed severe permanent deformation without an obvious fracture during loading at both times. There were statistically significant differences among the dimethacrylate-based materials. The dimethacrylate-based materials presented an increase in strength from 5 minutes to 1 hour and were as follows: Protemp 3 Garant (23.16 - 37.6 MPa), Temphase (22.27 - 28.08 MPa), Luxatemp (14.46 - 20.59 MPa). Protemp 3 Garant showed the highest value.

Temporary crown and fixed partial dentures are subjected to heavy and consistent loading by the mastication, and failure of the restoration frequently occurs. One of the common failure modes of the restorations which may lead to severe economic loss and patient discomfort is fracture.1 The materials used for temporary restoration must be strong particularly for long term use.2,3 The mechanical strength properties of the material are an important factor for the clinical success of temporary crown and fixed partial dentures.1 Although the mechanical properties of polymer-based crown and fixed partial denture materials have been reported previously by many researchers in terms of flexural strength, hardness and edge strength,1,4-11 there are few papers concerning their diametral tensile strength. The tensile strength is important because temporary restorations are prone to tensile failure. Although, the diametral tensile strength is a critical requirement, because many clinical failures are due to tensile stress.18 The diametral tensile strength test provides a simple method for measurement of the tensile strength of brittle materials. As it is not possible to measure the tensile strength of brittle materials directly, the British Standards Institution adopted the diametral tensile strength test.19 In this test, a compressive force is applied to a cylindrical specimen across the diameter by compression plates. While the stresses in the contact regions are indeterminate, there is evidence of a compressive component that hinders the propagation of the tensile crack. Large shear stresses that exist locally under the contact area may also induce a shear failure before tensile failure at the center of the specimen.7

The objectives of this study were to investigate the diametral tensile strength of polymer-based crown and fixed partial denture materials and to investigate the change of the diametral tensile strength with time. The null hypothesis to be tested was that there was no difference in the diametral tensile strength between monomethacrylate-based and dimethacrylated-based crown and fixed partial denture materials.

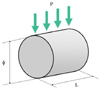

Polymer-based crown and fixed partial denture materials used in this study are presented in Table I. Specimens of the four materials were prepared in a cylindrical stainless steel mould which could be split so that no force would be required to remove the set specimen from the mould. The specimens had a size of 4 mm in diameter and 6 mm in length (Fig. 1). Protemp 3 Garant (PT3), Fast set Temphase (TMP) and Luxatemp (LXT) were injected into the mould with the automixing gun applicator, while Trim (TRM) was mixed with a clean plastic spatula for 30 seconds and immediately placed into the mould. The mould was covered with a glass slab and a plastic strip to prevent the inhibition of polymerization by oxygen, and hand pressure was applied to create flat end surfaces. After setting of the material, the mould was disassembled and the specimen was removed gently from the mould. For each material, twenty specimens were fabricated and randomly divided into two groups of ten according to the measurement time after completion of mixing.

The specimens of Group I were tested immediately (circa 5 min after completion of mixing). Specimens of Group II were prepared in the same method described above, and stored at 23℃ in a dry state for 1 hour before mechanical testing.

Diametral tensile strength of the specimens was investigated through a diametral compression test (indirect tensile test) in which a cylinder of material was compressed diametrically to failure. The diametral compression test was conducted using a Howden Universal Testing Machine (RDP Howden Ltd., Southam, Warks, UK) at 23 ± 1℃ operated at a compression rate of 0.5 mm/min. Specimens were placed with the flat ends perpendicular to the platens of the apparatus so that load was applied to the diameter of the specimens. The maximum load applied till failure of the specimens was recorded. The diametral tensile strength was calculated from the following equation.

where σ = the diametral tensile strength (MPa)

P = the maximum fracture load (N)

D = the diameter (mm) of the specimen

T = the length (mm) of the specimen

The mean values and standard deviations of the results were computed. The data were statistically analyzed using one-way ANOVA and the multiple comparison Scheffé test to determine whether statistically significant differences existed among the materials. Independent sample t test was also performed for each material to compare the diametral tensile strength between immediate and 1 hour specimens. For all statistical analyses, a significance level of 0.05 was used (SPSS, Version 10.1, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA).

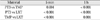

The mean strength values and standard deviations of each material are presented in Table II. Statistical analyses are presented in Tables III, IV, V.

TRM showed severe permanent deformation without an obvious fracture during loading at both times. Thus, the data for TRM were not presented (Table II).

At 5 minutes, PT3 showed the highest value (23.16 MPa), followed by TMP (22.27 MPa) and LXT (14.46 MPa). PT3 and TMP were significantly higher than LXT (P < .05) (Table II). PT3 and TMP were comparable (P = 0.694).

At 1 hour, the value of PT3 (37.6 MPa) was also the highest, followed by TMP (28.08 MPa) and LXT (20.59 MPa). There were significant differences among them (P < .05) (Table II).

The values for PT3, TMP and LXT at 1 hour were higher than those at 5 minutes. The strength was improved by 62.3% for PT3, 42.4% for LXT and 26.1% for TMP. Those increases in diametral tensile strength of PT3, TMP and LXT were significant with time (P < .001) (Table V).

A pure tensile test is problematic as brittle materials are liable to fracture at their gripped ends rather than show a single fracture along the midline of the specimen.12 One way to overcome this problem is to use dumbbell-shaped specimens, but the production of specimens of such geometry may not be easy in some materials such as dental amalgam. An alternative method is a diametral compression test which is a common method for measuring tensile strength of brittle materials.13 The diametral compression test is simple and offers good information about internal coherence of a material.14 Although the diametral compression test is applicable only for brittle materials, the test is appropriate for polymer-based materials and frequently used.13 However, if a specimen deforms excessively at the point of loading before fracture, the test may not be suitable for the specimen as it could lead to an invalid test result.15 Some polymer specimens do not show complete brittleness. Test on the specimens will give a type of flow test or early compressive strength rather than a proper diametral tensile strength.14 However, if a near-vertical fracture occurred and if the contact width is less than 20% of the specimen diameter, the test result can be accepted.16

All specimens tested in this study failed with vertical diametral cracks. They fractured into two pieces of approximately the same size along the midline of the specimen. They showed no measurable permanent deformation at the contact areas except TRM with an eye inspection. This confirms that the data were valid.

It was suggested that the water storage of resins at 37℃ has a tendency to lower the strength of the resins.17 Therefore, all specimens in this study were stored dry to eliminate any effects of water sorption.

The observed diametral tensile strengths ranged from 14.46 MPa to 23.16 MPa at 5 minutes and from 20.59 MPa to 37.59 MPa at 1 hour. These values are similar to those of resin core materials.12 It was found that diametral tensile strengths for chemically-cured core materials were 21.1 MPa - 31.6 MPa.12 PT3 showed significantly higher strength than the other materials investigated at both times. PT3 was 1.6 times stronger than the weakest material at 5 minutes after mixing, and 1.8 times stronger at 1 hour after mixing.

All test materials showed a uniform increase in strength from 5 minutes to 1 hour (P < .05). This increase can be explained by the setting reaction of polymer-based crown and fixed partial denture materials due to polymerization of thin type of polymer, what continues for several hours. According to the results, it can be concluded that the dimethacrylate-based materials (PT3, LXT and TMP) showed higher values in the diametral tensile strength than monomethacrylate-based material (TRM) as TRM exhibited such severe deformation that the strengths could not be measured under this test condition. Thus, the null hypothesis that there was no difference in the diametral tensile strength between monomethacrylate-based and dimethacrylate-based crown and fixed partial denture materials could be rejected. This can be explained by molecular structure of the materials. Chain scission occurs during fracture of the resins. The extent to which chain scission takes place depends upon the structure and morphology of the molecules. The dimethacrylate-based materials have a network structure which resists forces, while monomethacrylate-based materials allow movement of the molecules with relative ease under stress.

This study has shown that in dimethacrylate-based materials, the highest diametral tensile strength was shown by PT3. The different values between the materials shown in this study may be explained by different composition of the material, different filler type, different filler size, different filler distribution and different quantity of remaining double bonds, etc.11

When the test results were compared with the results by Kim and Watts, a generally positive correlation was observed between the edge strength at 0.5 mm from the edge and the diametral tensile strength at 1 hour after completion of the mixing (R = 0.92).1 The edge strength tended to be larger when the diametral tensile strength was large. This also means that these two properties tend to be determined by the same characteristics of the materials.

The diametral tensile strength of a polymer-based material is an important factor to be taken into account in selecting suitable materials for clinical use. These findings show that the monomethacrylate-based temporary restorations would be expected to be more susceptible to mechanical failure and less durable than the dimethacrylate-based temporary restorations when they are exposed to masticatory stresses.

1. The dimethacrylate-based crown and fixed partial denture materials (PT3, TMP and LXT) tested were stronger in diametral tensile strength than the monomethacrylate-based one (TRM) which showed severe deformation without fracture under the test conditions.

2. The diametral tensile strength of the materials investigated increased with time.

3. The diametral tensile strengths of all materials at 1 hour were about 1.3 - 1.6 times higher than those at 5 minutes after completion of mixing.

Figures and Tables

Table II

Means and standard deviation in parenthesis of diametral tensile strength of the materials investigated

Table III

One-way ANOVA test of the diametral tensile strengths of materials investigated at each time

References

1. Kim SH, Watts DC. In vitro study of edge-strength of provisional polymer-based crown and fixed partial denture materials. Dent Mater. 2007. 23:1570–1573.

2. Haselton DR, Diaz-Arnold AM, Vargas MA. Flexural strength of provisional crown and fixed partial denture resins. J Prosthet Dent. 2002. 87:225–228.

3. Koumjian JH, Nimmo A. Evaluation of fracture resistance of resins used for provisional restorations. J Prosthet Dent. 1990. 64:654–658.

4. Donovan TE, Hurst RG, Campagni WV. Physical properties of acrylic resin polymerised by four different techniques. J Prosthet Dent. 1985. 54:522–524.

5. Gegauff AG, Pryor HG. Fracture toughness of provisional resins for fixed prosthodontics. J Prosthet Dent. 1987. 58:23–29.

6. Khan Z, Razavi R, von Fraunhofer JA. The physical properties of a visible light-cured temporary fixed partial denture material. J Prosthet Dent. 1988. 60:543–544.

7. Craig RG. Mechanical properties. Restorative dental materials. c1997. 10th. St. Louis: Mosby;56–103.

8. Osman YI, Owen CP. Flexural strength of provisional restorative materials. J Prosthet Dent. 1993. 70:94–96.

9. Ireland MF, Dixon DL, Breeding LC, Ramp MH. In vitro mechanical property comparison of four resins used for fabrication of provisional fixed restorations. J Prosthet Dent. 1998. 80:158–162.

10. Kim SH, Watts DC. Effect of glass-fiber reinforcement and water storage on fracture toughness of polymer-based provisional crown and FPD materials. Int J Prosthodont. 2004. 17:318–322.

11. Asmussen E. Hardness and strength versus quantity of remaining double bonds. Scand J Dent Res. 1982. 90:484–489.

12. Combe CE, Shaglouf AMS, Watts DC, Wilson NHF. Mechanical properties of direct core build up materials. Dent Mater. 1999. 15:174–179.

13. Cho GC, Kaneko LM, Donovan TE, White SN. Diametral and compressive strength of dental core materials. J Prosthet Dent. 1999. 82:272–276.

14. Lange C, Bausch JR, Davidson CL. The influence of shelf life and storage conditions on some properties of composite resins. J Prosthet Dent. 1983. 49:349–355.

15. Jandt KD, Al-Jasser AMO, Al-Ateeq K, Vowles RW, Allen GC. Mechanical properties and radiopacity of experimental glass-silica-metal hybrid composites. Dent Mater. 2002. 18:429–435.

16. Pilliar RM, Filiaggi MJ, Wells JD, Grynpas MD, Kandel RA. Porous calcium polyphosphate scaffolds for bone substitute applications-in vitro characterization. Biomaterials. 2001. 22:963–972.

17. Coury TL, Miranda FJ, Duncanson MG. The diametral tensile strengths of various composite resins. J Prosthet Dent. 1981. 45:296–299.

18. McKinney JE, Antonucci JM, Rupp NW. Wear and microhardness of glass-ionomer cements. J Dent Res. 1987. 66:1134–1139.

19. British Standards Institution. British Standards Specification for Dental Glass Ionomer Cement BS 6039. 1981. 4.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download