Cryptorchidism is one of the most common congenital defects of the reproductive system in mammals, including dogs and human beings. It is caused by the failure of the scrotum of one or both testes to descent [

1]. The incidences of cryptorchidism are 0.8-9.7% in dogs [

2,

3,

4,

5] and 1-5% in human beings [

6]. In terms of breed predisposition in dogs, the incidence of cryptorchidism is highest in Chihuahuas, Boxers, and German Shepherds, with incidences of 30.4, 20.6, and 14.0%, respectively [

7].

Germ cells, Sertoli cells, and Leydig cells have the potential to proliferate in testicular tissue [

8,

9]. However, the abdominal testis is at increased relative risk of neoplasms such as Sertoli cell tumors and seminomas [

4,

10]. Approximately 70% of Sertoli cell tumors arising in abdominal testes are functional [

10,

11,

12]. The prevalence of testicular tumors is higher in dogs than in any other mammalian species [

13,

14].

GATA-binding proteins (GATA-1 to GATA-6) are structurally related zinc finger proteins and are expressed in blood-forming cells [

15,

16,

17], heart, gut, yolk sac endoderm, and gonads [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Among these GATAs, GATA-4 is expressed in mouse Sertoli and Leydig cells throughout fetal and postnatal testicular development [

23,

24].

There are some reports concerning the incidence of cryptorchidism in dogs [

2,

3,

4,

5,

7] and there are also morphological studies in cryptorchid boars [

25,

26]. However, there have been no previous reports of the morphology in the cryptorchid and control testis and epididymis of dogs. In this study, we investigated the morphological characteristics and cellular proliferative activity in spermatogenic cells and Sertoli cells in the cryptorchid and control testes and epididymides of a dog.

An 18-month-old German Shepherd with unilateral cryptorchidism was referred to the Seoul National University Veterinary Teaching Hospital, South Korea for elective orchidectomy. The left testis was present within the scrotum but the right testis was not palpable in the scrotum or inguinal area. Laparotomy revealed the cryptorchid testis in the right abdominal region. Both testes were surgically removed.

For histological analysis, both testes were fixed in neutral buffered formalin for 2 days and dehydrated with graded concentrations of alcohol before being embedded in paraffin. Paraffin-embedded tissues were sectioned using a microtome (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) into 3-micrometer coronal sections and were mounted onto silane-coated slides (Cat# 5116-20F, Muto Pure Chemicals Co., Ltd). The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) according to the standard protocol.

To ensure that the immunohistochemical data were comparable between control and cryptorchid testis/epididymis, the sections were carefully processed under the same conditions. The sections were hydrated and treated with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 30 min. For antigen retrieval, the sections were placed in 400-mL jars filled with citrate buffer (pH 6.0) and heated in a microwave oven (Optiquick Compact, Moulinex) operating at a frequency of 2.45 GHz and a 800-W power setting. After three heating cycles of 5 min each, slides were allowed to cool to room temperature and were washed in PBS. After washing, the sections were incubated in 10% normal goat serum in PBS for 30 min. They were then incubated with rabbit anti-Ki67 antibody (1:1,000; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), mouse-anti-proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA, 1:1,000) or GATA-4 (1:500, SantaCruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) for 48 h at 4℃. They were then exposed to biotinylated goat antirabbit IgG, streptavidin peroxidase complex (diluted 1:200, Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA), and visualized with 3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Sigma) in 0.1 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4).

Thirty sections per tissue (control or cryptorchid) were selected from the corresponding areas of each level of testis or epididymis. The number of Ki67-positive or GATA-4 positive cells in each group of sections was counted in the seminiferous tubules using an image analyzing system equipped with a computer-based CCD camera (software: Optimas 6.5, CyberMetrics, Scottsdale, AZ, U.S.A.). Cell counts were obtained by averaging the counts from three seminiferous tubules per section (10 sections).

The data shown here are presented as mean and standard errors of counts performed for each area. The data were evaluated by Student's t-test. Results were considered statistically significant if P<0.05.

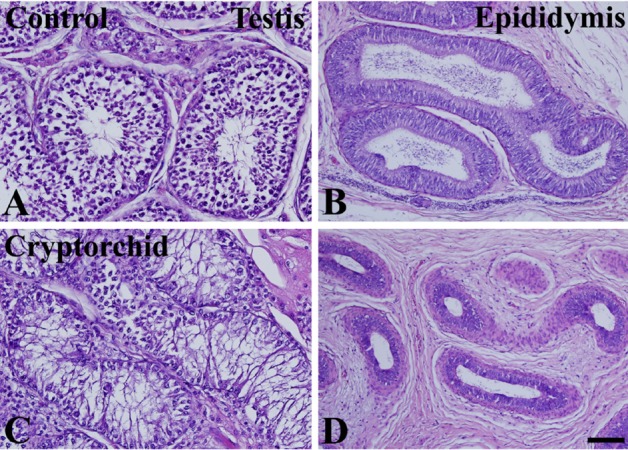

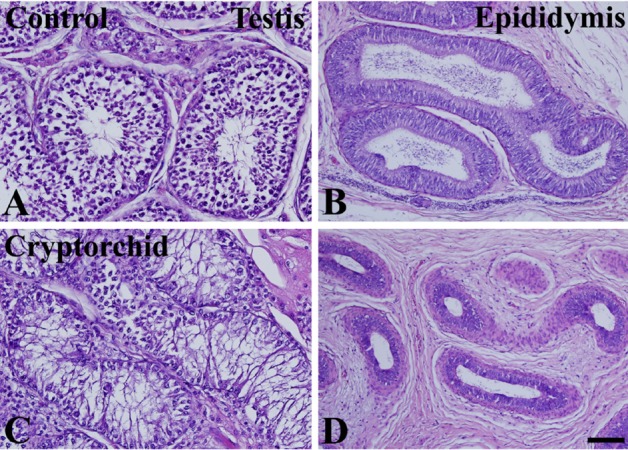

In the control testis and epididymis, normal spermatogenesis was observed in H&E-stained sections. Many germ cells and Sertoli cells were observed in the basal seminiferous epithelium of seminiferous tubules. Spermatocytes and spermatids were detected in the vicinity of the lumen in seminiferous tubules (

Figure 1A). In the epididymis, cross-sections of the epididymal duct were clearly observed and spermatids were located in the lumen of the duct (

Figure 1B). In the cryptorchid testis, few cells were observed in the basal seminiferous epithelium of seminiferous tubules. In addition, spermatocytes and spermatids were rarely observed in the seminiferous tubules (

Figure 1C). In the epididymis, the lumen of the epididymal duct was relatively small compared to that in the control epididymis, and interstitial tissue was abundant. In addition, only a few spermatids were observed in the lumen of the epididymal duct (

Figure 1D).

| Figure 1Photomicrographs of hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of testis (A and C) and epididymis (B and D) in unilateral cryptorchidism. In control (intact) testis (A) and epididymis (B), normal spermatogenesis and epididymal duct are present, respectively. In the cryptorchid testis (C), most cells are Sertoli cells, and there are relatively few spermatogonia and spermatocytes. In the cryptorchid epididymis (D), the diameter of the epididymal duct is relatively small.

|

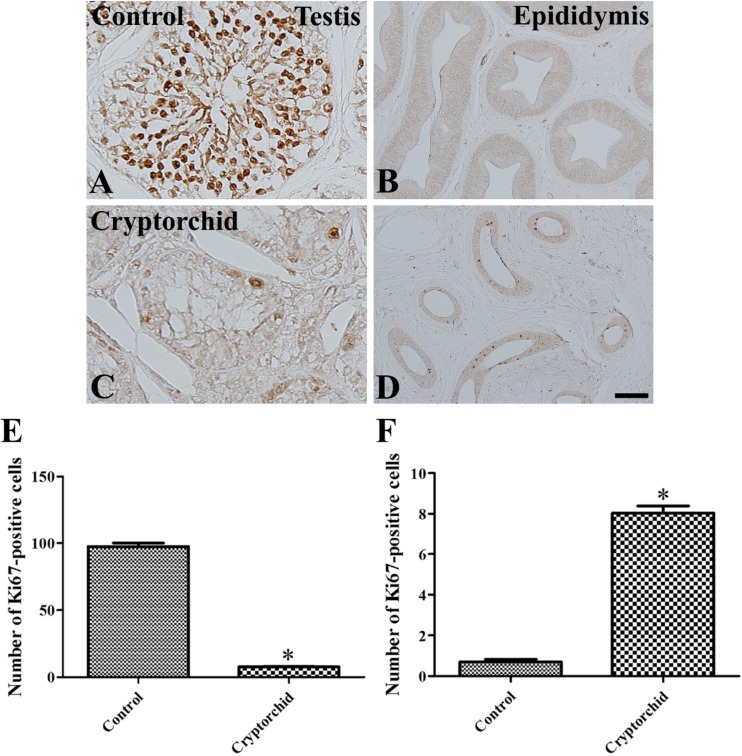

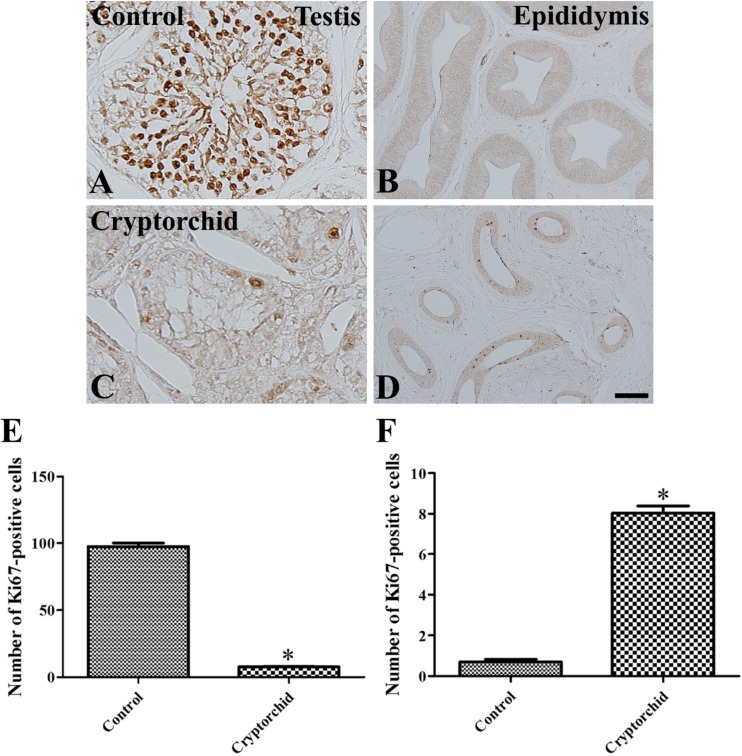

In the control testis, abundant Ki67-positive cells were observed in the seminiferous tubules, although there were relatively few Ki67-positive cells in the basal seminiferous epithelium of seminiferous tubules (

Figure 2A). Few Ki67-positive cells were observed in the epididymal duct (

Figure 2B). In the cryptorchid testis, a few Ki67-positive cells were detected in the basal seminiferous epithelium of seminiferous tubules (

Figure 2C), and a few Ki67-positive cells were also observed in the epididymal duct (

Figure 2D).

| Figure 2Immunohistochemistry for Ki67 in testis (A and C) and epididymis (B and D) in unilateral cryptorchidism. In the control testis (A), a Ki67-positive reaction is detected in most cells, except in the basal seminiferous epithelium of the seminiferous tubules. In the control epididymis (B), Ki67-positive cells are not observed. In the cryptorchid testis (C), Ki67-positive cells are present in the basal seminiferous epithelium of seminiferous tubules. In the cryptorchid epididymis (D), Ki67-positive cells are present in the epididymal duct. E and F: The number of Ki67-positive cells per each seminiferous tubule/epididymal duct in testis and epididymis, respectively, in unilateral cryptorchidism (10 sections; *P<0.05, control vs. cryptorchid group). All data are shown as the mean±SE.

|

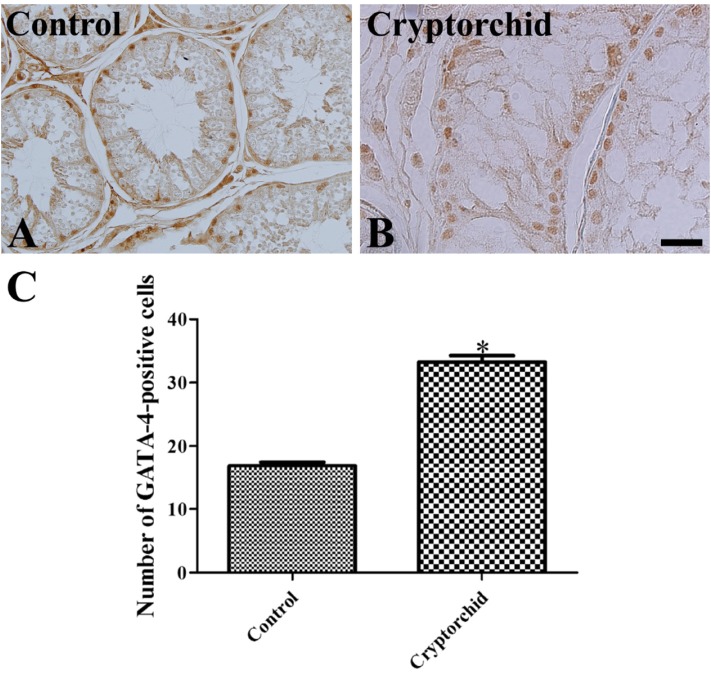

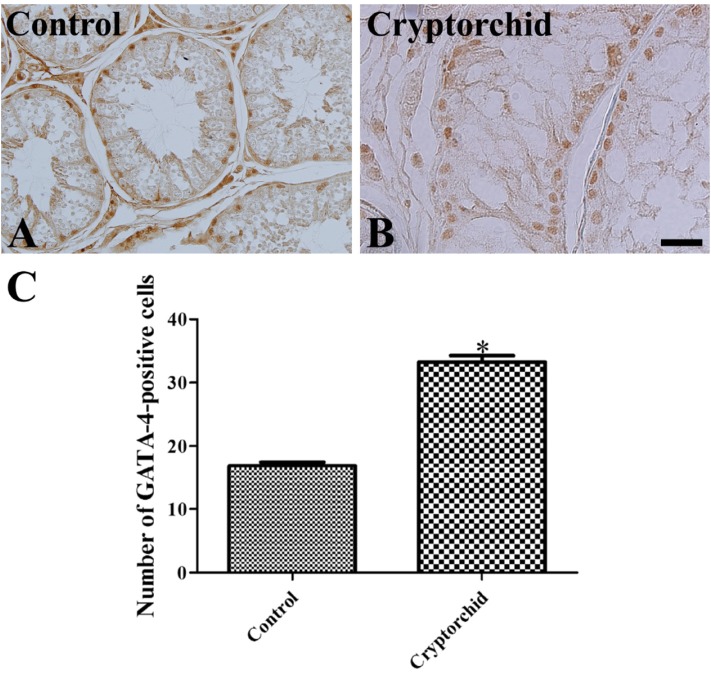

In both control and cryptorchid testis, GATA-4 positive cells were detected in the basal seminiferous epithelium of seminiferous tubules (

Figure 3A, 3B). However, the numbers of GATA-4 positive cells were greater in the cryptorchid testis than in the control testis (

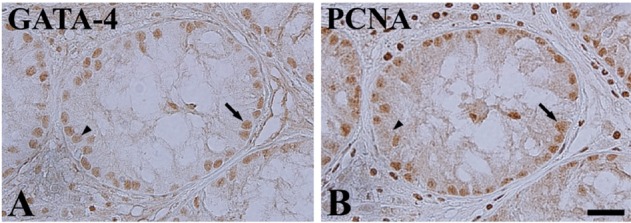

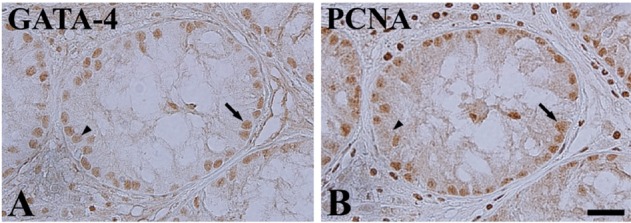

Figure 3C). In the cryptorchid testis, GATA-4 positive cells were also stained with PCNA (

Figure 4A, 4B).

| Figure 3Immunohistochemistry for GATA-4 in testis (A and B) in unilateral cryptorchidism. In the control (A) and cryptorchid (B) testis, GATA-4 positive cells are present in the basal seminiferous epithelium of seminiferous tubules. GATA-4 positive cells are abundant in the cryptorchid testis as compared to the control testis. C: The number of GATA-4 positive cells per seminiferous tubule in testis in unilateral cryptorchidism (10 sections; *P<0.05, control vs. cryptorchid group). All data are shown as the mean±SE.

|

| Figure 4Immunohistochemistry for GATA-4 and PCNA in mirror-imaged testis sections in unilateral cryptorchidism. Most GATA-4 positive cells (arrow) are also labeled with PCNA, but some GATA-positive cells are not co-localized with PCNA (arrowhead).

|

In dogs, cryptorchidism is a common disorder and is mainly of genetic origin [

11]. In the present study, we observed the morphology of the control and cryptorchid testes and epididymides in a dog. The unilateral cryptorchidism affected the right testis. The right testis is more frequently affected because it develops in a more cranial position than the left and has a longer distance to travel to reach the scrotum [

7,

27,

28]. There was a significant reduction in the numbers of spermatogonia, spermatocytes, and spermatids in the cryptorchid testis as compared to the control testis. The diameter of the epididymal duct was significantly decreased in the cryptorchid epididymis compared to that in the control epididymis. In addition, the interstitial tissue was relatively abundant in the cryptorchid epididymis. This finding that cryptorchidism changes the histology of the lamina propria, spermatogenic tissue, and interstitial tissue in the testis, resulting in a significant reduction in the number and diameter of seminiferous tubules [

26] and a decrease in the number of spermatogonia [

29], which results in a reduction in fertility [

6] is consistent with that of previous reports.

In the control testis, Ki67-positive cells were abundant in most cells in the seminiferous tubules, but were not detected in the epididymal duct. However, in the cryptorchid testis, Ki67-positive cells were only detected in the basal seminiferous epithelium of seminiferous tubules. In addition, Ki67-positive cells were observed in the epididymal duct of the cryptorchid epididymis. This result is consistent with that of a previous study, which found that cell proliferation (as determined by proliferating cell nuclear antigen-positive cells) significantly decreased in experimentally induced cryptorchidism [

30]. The proliferative activity of spermatogonia is decreased in cryptorchid testes of male children [

31], boars [

25] and rabbits [

29]. Most proliferating cells in the cryptorchid testis were identified as Sertoli cells based on mirrorimage immunohistochemistry for PCNA and GATA-4. This finding suggests that Sertoli cells in the cryptorchid testis can proliferate and this may increase the risk of Sertoli cell tumors in the cryptorchid testis. This result is consistent with that of previous reports that the prevalence of Sertoli cell tumors in cryptorchid testes of dogs is much higher than that in scrotal testes [

4,

10,

32].

It has been reported that 1-3% cells are proliferating in the epididymal duct of 2.5-month-old rats, and the cell proliferation decreases with age [

33]. In the present study, Ki67-positive cells were rare in the control epididymis, while in the cryptorchid epididymis the number of Ki67-positive cells significantly increased. This result suggests that the epithelium in cryptorchid epididymis can proliferate.

We observed that the cryptorchid testis and epididymis showed defects in morphology, and that cell proliferation was pronounced in the Sertoli cells of the cryptorchid testis and in the epididymal duct. These results indicate that Sertoli cells in the cryptorchid testis have the potential to proliferate, and that this may be associated with the high prevalence of Sertoli cell tumors in cryptorchid testes in dogs.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download