Abstract

Group formation of rhesus monkeys, often leads to victims of repeated attacks by the high ranking animal. We reported a case of an injured middle ranking monkey from repetitive and persistent aggression. 4-male rhesus group was formed by a rapid group formation strategy 2 years ago. One monkey in the group suddenly showed depressive and reluctant movement. Physical examination revealed multiple bite wounds and scars in the dorsal skin. Overall increased opacity of the dorsal soft tissue and some free air was observed on radiographic examination. An unidentified anaerobic gram negative bacillus was isolated from the bacterial culture. Reconstructive surgery was performed and in consequence, the wound was clearly reconstructed one week later. Eventually, the afflicted monkey was separated and housed apart from the hierarchical group. This case report indicate that group formation in rhesus monkeys is essentially required sufficient time and stages, as well as more attention and a progressive contact program to reduce animal stress and fatal accidents.

Go to :

Housing system is considered very important in laboratory non-human primates, because these species have the property of emotional and social interaction. Group housing is widely accepted as the most appropriate housing condition for nonhuman primates. A number of studies have demonstrated that singly caged primates show signs of distress and general poor welfare [1,2,3]. Although group housing has virtually a lot of positive effects, group formation is not always simple and easy in hierarchical nonhuman primates. Therefore, research on group formation could produce mixed results according to the period of contact, as well as structural complexity of the house. For example, some rhesus macaques showed aggressive and affiliative behavior during group formation using simultaneous versus staged strategies [4]. It was found that increased structural complexity and visual cover did not decrease contact aggression during formation of rhesus macaque groups [5]. Hierarchy is another issue to be considered when forming primate social groups. Establishment of a dominance hierarchy has been viewed as a potent psychosocial stressor with potentially greater effects on lower ranking animals [6]. Therefore, social group formation could be discontinued due to excessive violent aggression and an unacceptably high death rate. In this report, we showed that inappropriate social group formation could wound latently lower or middle ranking rhesus monkeys during group housing. Consequently, appropriate surgical intervention and quick separation can be of great help to the injured monkey for improved physical and psychosocial status.

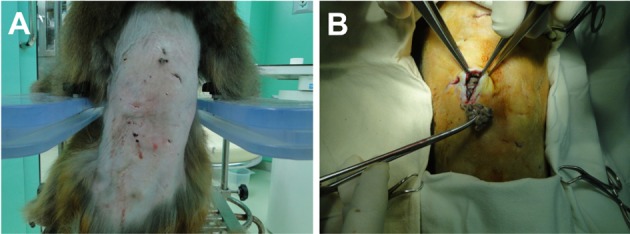

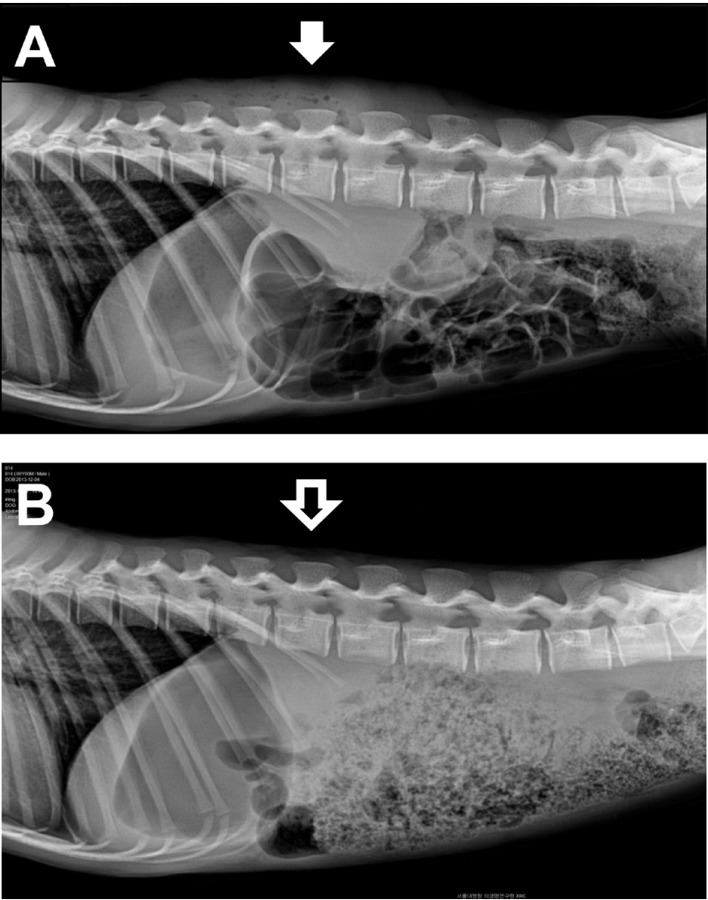

A male 6-year-old rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta), showed sudden lowered appetite and activity. 2 years ago, this monkey was released over a period of one week for a study. Fortunately, this monkey had adjusted to the other 3-male monkeys without particular problems. One of the monkeys developed suppressive and cringing behavior. Surprisingly on physical examination, profuse purulent discharge and cystic mass was detected on the back (Figure 1A). Vital signs including body temperature, heart rate, and respiratory rate were within normal range. Multiple bite wounds and extended scars in the middle of the dorsal skin were observed after hair clipping in the injured monkey. Overall increased opacity of the dorsal soft tissue and some free air was observed on lateral view of the thoracolumbar spine, on radiographic examination (Figure 2A). We concluded that this suppurative and granulomatous wound had occurred due to chronic and repeated bite injury. Bacterial culture from the wound and reconstructive surgery was performed. A large amount of necrotic debris and pus was removed during a surgical intervention, and washed out with normal saline (Figure 1B). Two silicone drainage tubes were placed under the skin to remove remaining inflammatory discharge.

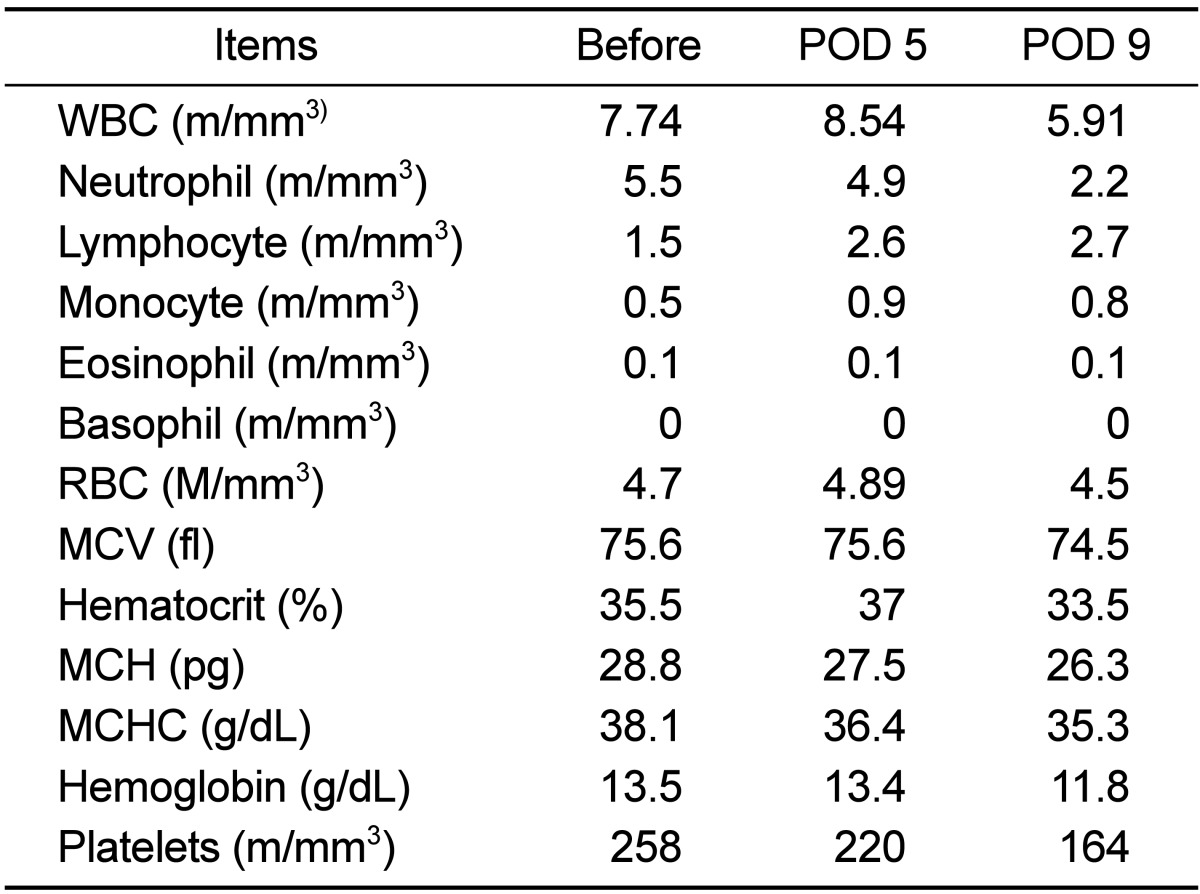

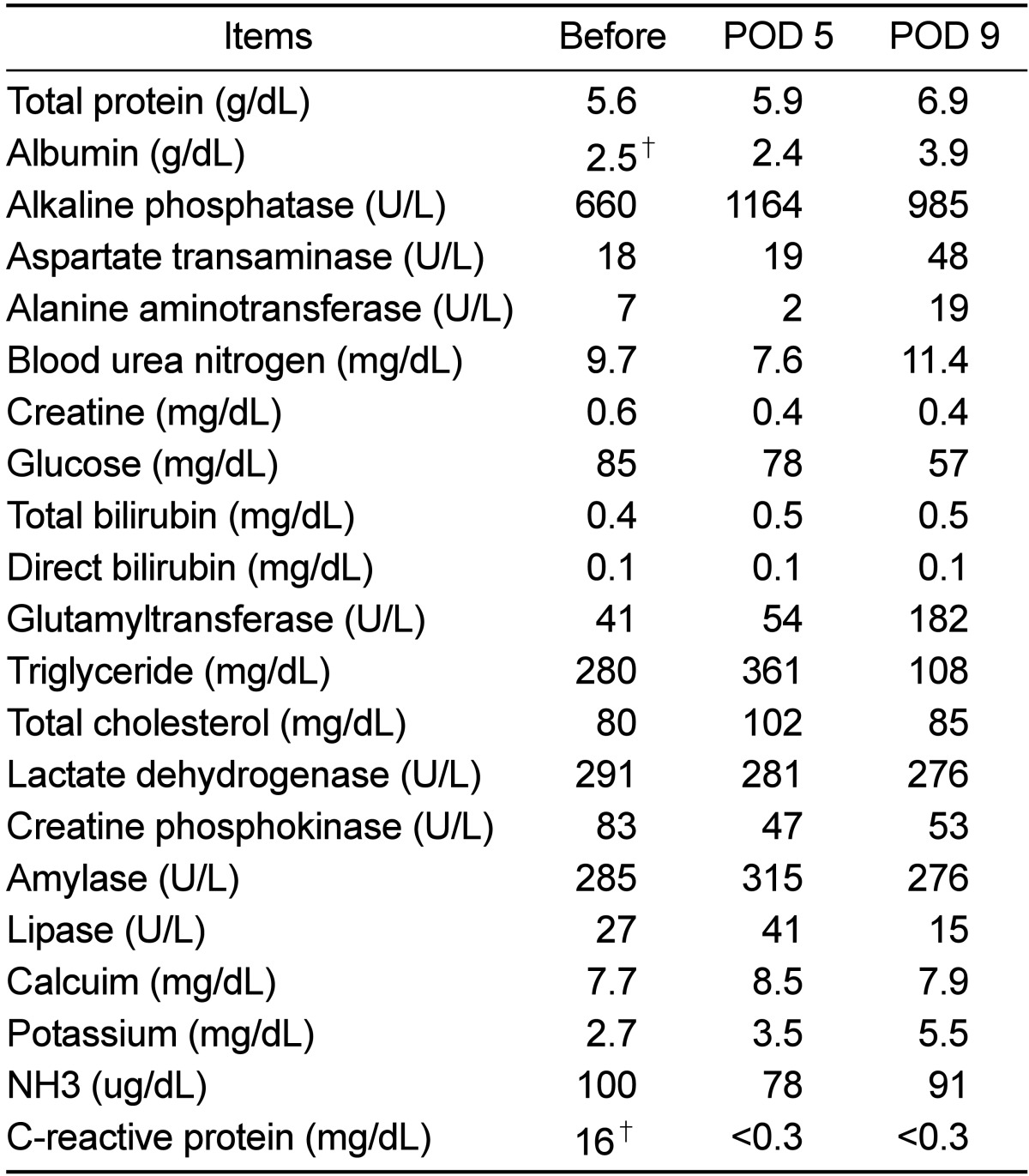

Laboratory profile showed no remarkable finding in CBC analysis (Table 1), but hypoalbuminemia (2.5 g/dL) and a high level of C-reactive protein (16 mg/dL) were recorded in the serum chemistry results (Table 2). Antibiotics (Cefotaxim, 50 mg/kg, bid, IV) and anti-inflammatory drugs (Meloxicam, 0.1-0.2 mg/kg, sid, IV or IM) had been administered for 7 days post-operatively. Wound dressing was performed every other day. Appetite and activity of the monkey improved gradually on medical treatment, and the volume of wound exudate significant decreased with time. All laboratory profiles, including CBC and serum chemistry were normalized on day 9. Previous opacity of the dorsal soft tissue had complete disappeared on the follow-up radiographs (Figure 2B). Unidentified anaerobic gram negative bacillus was isolated from the bacterial culture using phenylalanine agar and brucella agar. Eventually, the monkey was separated from the group and housed in a single cage for a long time to avoid hierarchical distresses.

Traumatic wound is a common medical problem requiring treatment in single, pair or group-housed primates. Therefore, close observation and careful management are required to preventing traumatic or bite wound in the husbandry of rhesus monkeys [7]. We reported severe suppurative bite wounds by repetitive aggression from the high ranking monkey during group housing. Linear dominance hierarchies that characterize many nonhuman primate social groups are established in a large part by dyadic agonistic interactions, and are maintained by aggressive, submissive and affiliative behaviors [8]. Dominant monkeys (i.e. those above the median in social rank) typically have greater control over resources, and maintain their status through physical aggression and/or intimidation [9]. It is not known for how long persistent aggressive behaviors lead to recessive hierarchies. This depends on variable environments, including contact period, group formation strategy and structural conditions. Westergaard et al [10] reported that the wounding rate was 3 fold higher in rapid formation of groups than staged formation groups during the first year after group formation. However, it was markedly decreased 2 years later in rapid formation of groups. In addition, the wounding rates were higher for animals in undivided vs. divided corrals as well as for males vs. females. These results indicate that group formation method and corral design influence rates of traumatic wounding among adult males.

In this case, despite the rapid group formation of only one week, severe aggression or intimidation was not revealed in the initial stage. However, the dominant monkey might have been traumatizing the recessive monkey since then. The conflict of dominance hierarchies may have persisted for a long time to control and maintain their group. Therefore, when aggressive harassment was intensive and persistent, the subordinate monkeys can occasionally be victims of repeated and potentially fatal violence. Consequently, group housing of previously single caged adult rhesus macaques was associated with considerable risks which were not overcome by systematically familiarizing all group members before the animals were introduced as a group. Incrementally releasing subgroups of animals and incorporating a housing design that facilitates visual and social separation of individuals will be more effective strategies for reducing rates of traumatic wounding when forming multi-male rhesus macaque group. In summary, our report demonstrated that group housing formation needs sufficient time and stages, as well as more attention and a progressive contact program to avoid fatal consequences. Furthermore, adequate housing systems (e.g. devices) will helpful to reduce animal stress and associated demands on veterinary and animal management resources following formation of rhesus macaque groups.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Taehyeong Lee for animal care.

Go to :

References

1. McKinney WT Jr. Primate social isolation. Psychiatric implications. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1974; 31(3):422–426. PMID: 4415204.

2. Olsson IAS, Westlund K. More than numbers matter: The effect of social factors on behaviour and welfare of laboratory rodents and non-human primates. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2007; 103:229–254.

3. Reinhardt V, Houser D, Eisele S. Pairing previously singly caged rhesus monkeys does not interfere with common research protocols. Lab Anim Sci. 1989; 39(1):73–74. PMID: 2918690.

4. Bernstein IS, Gordon TP, Rose RM. Factors influencing the expression of aggression during introductions to rhesus monkeys groups. In : Holloway RL, editor. Primate aggression, territoriality, and xenophobia: a comparative perspective. New York: Academic Press;1974. p. 211–240.

5. Fairbanks LA, McGuire M, Kerber W. Effects of group size, composition, introduction technique and cage apparatus on aggression during group formations in rhesus monkeys. Psychol Rep. 1978; 42(1):327–333. PMID: 417359.

6. Rose RM, Bernstein IS, Gordon TP. Androgen and aggression: A review and recent findings in primates. In : Holloway RL, editor. Primate aggression, territoriality, and xenophobia: a comparative perspective. New York: Academic Press;1974. p. 275–304.

7. Lee JI, Lee CW, Kwon HS, Chung DH, Park CG, Kim SJ, Kang BC. Prevalence and causes of wound of rhesus monkey in the laboratory nonhuman primate facility. Lab Anim Res. 2008; 24:293–296.

8. Kaplan JR, Manuck SB, Clarkson TB, Lusso FM, Taub DM. Social status, environment, and atherosclerosis in cynomolgus monkeys. Arteriosclerosis. 1982; 2(5):359–368. PMID: 6889852.

9. Kaplan JR, Manuck SB. Ovarian dysfunction, stress, and disease: a primate continuum. ILAR J. 2004; 45(2):89–115. PMID: 15111730.

10. Westergaard GC, Izard MK, Drake JH, Suomi SJ, Higley JD. Rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta) group formation and housing: wounding and reproduction in a specific pathogen free (SPF) colony. Am J Primatol. 1999; 49(4):339–347. PMID: 10553961.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download