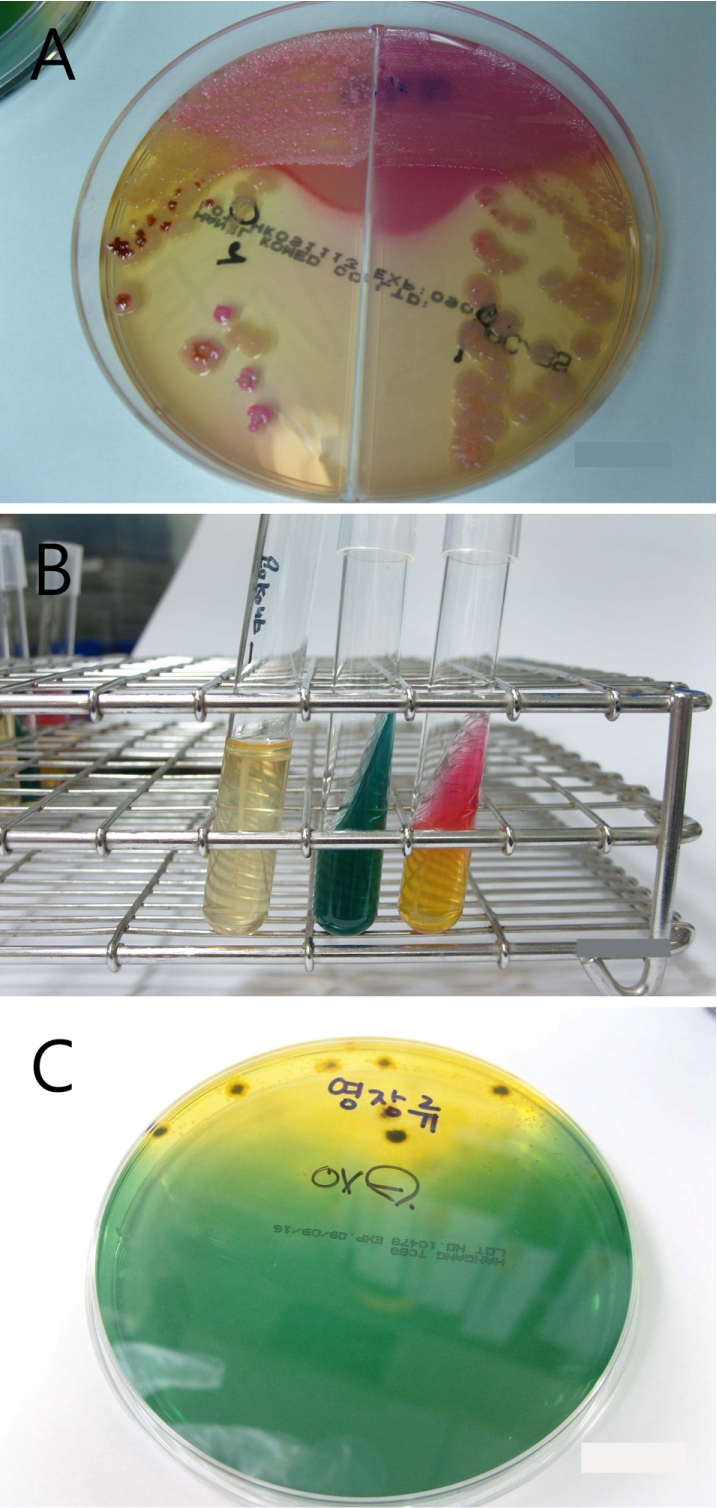

| Figure 2(A) Colorless or black colonies grown on the Mac/SSa were subcultured in BAP. (B) IMVIC test showed negative for indole, motility and H2S in SIM broth, negative in citrate and K/A in triple sugar iron agar. (C) Oxidase-negative result was seen for colony grown in thiosulfate-citrate-bile-sucrose media. |

Abstract

A 3.4 year-old rhesus macaque weighing 4.5 kg, was suffering from anorexia, acute mucous and bloody diarrhea. On physical examination, the monkey showed a loss of activity, hunched posture, abdominal pain, dehydration, mild gingivitis and unclean anus with discharge. Whole blood was collected for the examination of electrolytes, hematology and serum chemistry; fresh stool was also collected for bacterial culture. Blood profiles showed leukocytosis (14.5 K/µL) and neutrophilia (11.0 K/µL) on complete blood cell count and imbalanced electrolytes associated with diarrhea. As a result of bacterial culture, Shigella flexneri was identified through Mac/SS, IMVIC test, TCBS and VITEK II. Based on these results, this monkey was diagnosed as having acute enteritis caused by Shigella flexneri. Treatment was performed with enrofloxacin prior to the isolation of Shigella flexneri to prevent the transmission of disease. Fortunately, mucus and bloody diarrhea did not persist and general conditions fully recovered. Our results show that the use of enrofloxacin is effective in controlling Shigella flexneri infection in newly acquired rhesus monkeys.

Go to :

Shigella is gram-negative bacterium that causes bacillary dysentery in human and non-human primates [1-4]. Shigella flexneri belonging to the B subgroup of the genus is a well-known pathogen for primates, chiefly responsible for morbidity and mortality in colonized monkeys [5]. Bloody diarrhea and mucus discharge is often accompanied with abdominal pain, tenesmus, fever, anorexia, weight loss and dehydration. In colonies of research macaques, Shigella infections are spread by the fecal-oral route, originating from the addition of animals that are asymptomatic carriers, either from the wild or from other colonies [1,6]. In humans, persons traveling in areas with poor sanitation and crowded conditions become particularly susceptible to such diseases [7-9]. Importantly, Shigella is a zoonotic organism which could present in people working with nonhuman primates or vice versa.

Currently, a vaccine for Shigella has not been licensed in the United States and the organism quickly becomes resistant to medication. During the past 10 years, several live, attenuated oral Shigella vaccines, including the strains WRSs1, WRSs2 and WRSs3, are acceptable candidates for continued development as human Shigella sonnei vaccines [10]. However, commercial vaccine of Shigella is not yet used in the clinic for human and nonhuman primates. Thus, veterinary clinicians must assume shigellosis by clinical signs and instigate appropriate therapy or wait 24 to 48 h for the results of bacterial culture. For this reason, regular screening is necessary to prevent spreading of this pathogen to other individuals or colonies.

Recently, China has become one of the major breeders and suppliers of macaques for the biotech, pharmaceutical and medical communities worldwide. Also, our requirement of these animals is increasing in the field of biomedical research. Therefore, adequate prevention and prompt treatment of this pathogen is required to preserve a source of laboratory nonhuman primates in our country.

Here, we report that a newly acquired rhesus monkey infected by Shigella flexneri was precisely diagnosed and successfully treated with enrofloxacin. In addition, prompt treatment against this pathogen could control the spread of disease and preserve healthy colonies.

A 3.4-year-old male rhesus macaque, weighing 4.5 kg, was suffering from anorexia, acute mucous production and bloody diarrhea. The colony including this monkey was screened by the exporting country for bacterial and parasitic pathogens, such as Mycobacterium, Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia and endo/ecto parasites. This rhesus macaque was imported from China and finished the legal quarantine process. Then, the colony including this monkey was acclimating at a laboratory animal facility which maintained at was 24±4℃ and a relative humidity of 50±10% with artificial lighting and a 12:12 light-dark cycle (7:00 AM onset) as well as with 13-18 air changes per h. This monkey was housed in an individual home cage and had daily provided food (PS DIET®, Oriental Yeast Co, Ltd, Japan and fresh fruits) and unlimited access to water. The animal was managed by the National Institutes of Health "Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals".

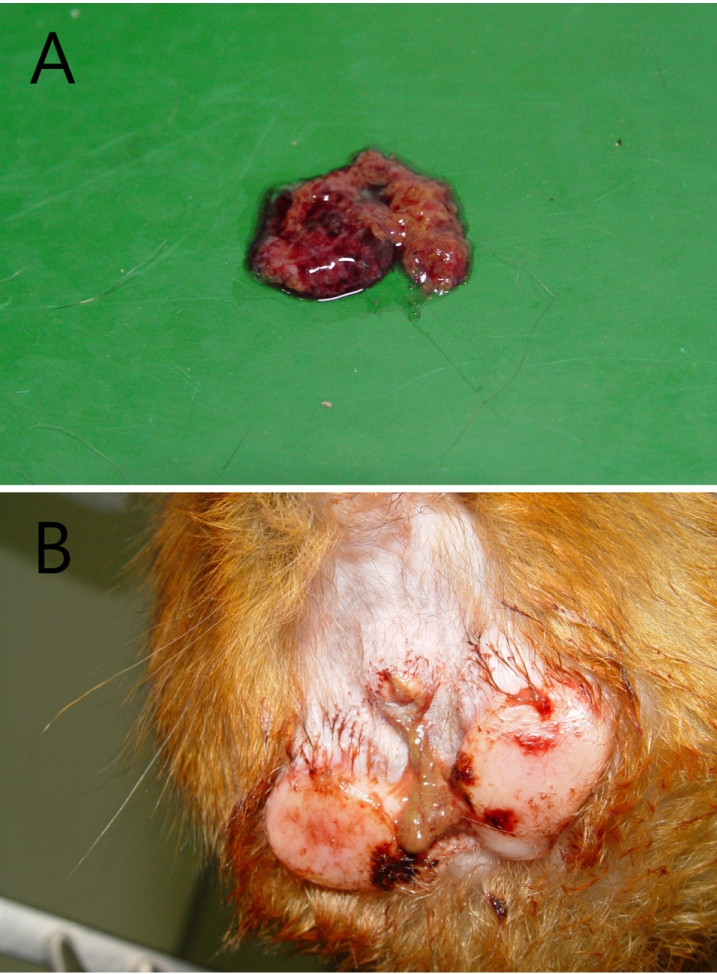

Fresh bloody diarrhea persisted for two days and gradually increased infrequency and volume, along with a foul smell (Figure 1A). The perianal region was unclean with a bloody discharge (Figure 1B). Vital signs recorded were as follows: body temperature (39.2), heart rate (250 beats/min) and respiratory rate (44 breaths/min). On physical examination, the monkey showed a loss of activity, hunched position, abdominal pain, dehydration and mild gingivitis. Differential diagnosis included parasitic, bacterial and viral infection. To rule out these factors, bloody stool was collected immediately for bacterial culture and then other laboratory tests were performed. Laboratory profiles revealed leukocytosis (14.5 K/µL) and neutrophilia (11.0 K/µL) on complete blood cell count as well as hyponatremia (139 mmol/L), hypokalemia (3.1 mmol/L) and hypochloremia (99 mmol/L) on electrolytes, and a normal range for serum chemistry. Based on the clinical signs, presumptive diagnosis was made as dysentery by Shigella, Vibrio or Campylobacter species. Preferentially, enrofloxacin (5 mg/kg, sid, intravenous or intramuscular injection) as an antibiotic for bacillary dysentery infection was administered for 3 days; bacterial cultures and parasitic examinations were also performed. No evidence of parasitic infection was found in the stool. On the other hand, the bacterial culture results showed growth of an unidentified organism.

To identify the organism, bloody stool samples were inoculated on MacConkey/Salmonella-Shigella agar (Mac/SSa) (Hanil Komed, Seoul, Korea) and incubated at 37℃. Colorless or black colonies grown on Mac/SSa were subcultured in blood agar (Figure 2A). An IMVIC (Hanil Komed) test was negative for indole, motility and H2S in SIM broth, and negative in citrate, and K/A in triple sugar iron (TSI) agar (Figure 2B). Also, colonies grown in thiosulfate-citrate-bile-sucrose (TCBS) media were negative for oxidase (Figure 2C). Vibrio spp. and Campylobacter spp. were not detected in mCCDA and TCBS media. Finally, through the serological grouping using VITEK II, the organism was identified as Shigella flexneri. Consequently, the monkey was diagnosed as enterocolitis caused by Shigella flexneri and was continually treated with enrofloxacin. At post-onset day 5, bloody diarrhea completely disappeared and general body conditions recovered.

Asymptomatic carriers are common, especially in new world monkeys, and bacteriological screening is known to have low sensitivity [11]. Quarantine stations may perform routine stool-screening for enteric pathogens and commence antibiotic treatment, but this does not guarantee that animals remain free of infection on delivery to a primate facility. Organisms may continue to be shed intermittently, commonly at times of stress, such as when animals are in transit [11]. In these cases, the infected monkey has been examined regularly for enteric pathogens at the animal's breeding and pre-embarkation quarantine facility, and all animals are documented as negative in the individual records. However, a latent pathogen in this monkey was revealed at the time of post-transport and post-quarantine processes.

Clinical symptoms of shigellosis include mucus and bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and fever. Affected monkeys are weak and moderately to severely dehydrated, and they require prompt medical treatment to correct life-threatening fluid and electrolyte imbalances [12]. Fortunately, this monkey showed rapid recovery from the illness without electrolyte correction.The enteric pathogen Shigella flexneri has also been implicated as a cause of periodontal disease [13,14]. This animal also showed mild gingivitis at both the upper/lower periodontal region, but has since been terminated. Diagnosis was based on clinical signs and isolation of the organism from deep rectal swabs and fresh stool specimens. Culture and isolation of the organism is facilitated by the use of selective media such as selenite broth and SSa agar [15].

Currently, no Shigella vaccine has been licensed, although several are under development [16-20]. China does not vaccinate for laboratory nonhuman primate colonies. For that reason, there is very high potential that asymptomatic carriers may spread pathogens to other monkeys or colonies. In this case, the infected monkey was newly imported from China and just finished the quarantine process when it showed clinical signs. It is suspected that asymptomatic monkeys reveal clinical signs by transport or environmental stress.

In this case, treatment of shigellosis was performed very rapidly and was completed by enrofloxacin administration. Enrofloxacin is a widely utilized antibiotic in veterinary medicine that has antibacterial activity against both gram-negative and gram-positive organisms [21,22]. Enrofloxacin is generally regarded as not only an efficacious antibiotic, but also a safe drug [23].This treatment regimen was suggested successful in controlling Shigella in rhesus monkey based on clinical signs and successive cultures of rectal swabs from the infected monkey. In summary, our case suggests that a newly acquired rhesus monkey can be infected by Shigella flexneri, even with previous screening of bacterial and parasitic pathogens by the exporting country. It is considered that the infected monkey was an asymptomatic carrier and revealed clinical symptoms due to stressful environmental changes. Regular screening tests, control of transmission and aggressive treatment for this pathogen are essential for preservation of healthy nonhuman primate facilities.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by a grant from the Korea Health 21 R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (Project No.: A040004).

Go to :

References

1. Banish LD, Sims R, Sack D, Montali RJ, Phillips L Jr, Bush M. Prevalence of shigellosis and other enteric pathogens in a zoologic collection of primates. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1993; 203(1):126–132. PMID: 8407446.

2. Kelly-Hope LA, Alonso WJ, Thiem VD, Anh DD, Canh do G, Lee H, Smith DL, Miller MA. Geographical distribution and risk factors associated with enteric diseases in Vietnam. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007; 76(4):706–712. PMID: 17426175.

3. Pucak GJ, Orcutt RP, Judge RJ, Rendon F. Elimination of the Shigella carrier state in rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) by trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. J Med Primatol. 1977; 6(2):127–132. PMID: 875006.

4. Talukder KA, Mondol AS, Islam MA, Islam Z, Dutta DK, Khajanchi BK, Azmi IJ, Hossain MA, Rahman M, Cheasty T, Cravioto A, Nair GB, Sack DA. A novel serovar of Shigella dysenteriae from patients with diarrhoea in Bangladesh. J Med Microbiol. 2007; 56:654–658. PMID: 17446289.

5. Good RC, May BD, Kawatomari T. Enteric pathogens in monkeys. J Bacteriol. 1969; 97(3):1048–1055. PMID: 4180466.

6. Vickers JH. Infectious diseases of primates related to capture and transportation. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1973; 38(2):511–513. PMID: 4347673.

7. Beecham HJ 3rd, Lebron CI, Echeverria P. Short report: impact of traveler's diarrhea on United States troops deployed to Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997; 57(6):699–701. PMID: 9430530.

8. Thornton SA, Sherman SS, Farkas T, Zhong W, Torres P, Jiang X. Gastroenteritis in US Marines during Operation Iraqi Freedom. Clin Infect Dis. 2005; 40(4):519–525. PMID: 15712073.

9. Riddle MS, Sanders JW, Putnam SD, Tribble DR. Incidence, etiology, and impact of diarrhea among long-term travelers (US military and similar populations): a systematic review. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006; 74(5):891–900. PMID: 16687698.

10. Collins TA, Barnoy S, Baqar S, Ranallo RT, Nemelka KW, Venkatesan MM. Safety and colonization of two novel VirG(IcsA)-based live Shigella sonnei vaccine strains in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). Comp Med. 2008; 58(1):88–94. PMID: 19793462.

11. Kennedy FM, Astbury J, Needham JR, Cheasty T. Shigellosis due to occupational contact with non-human primates. Epidemiol Infect. 1993; 110(2):247–251. PMID: 8472767.

12. Bernacky BJ, Gibson SV, Kelling ME, Abee CR. Fox JG, editor. Nonhuman Primates. Laboratory Animal Medicine. 2002. 2nd ed. Amsterdam: Academic Press;p. 730–732.

13. Armitage GC, Newbrun E, Hoover CI, Anderson JH. Periodontal disease associated with Shigella flexneri in rhesus monkeys. J Periodontal Res. 1982; 17(2):131–144. PMID: 6124590.

14. Armitage GC, Banks TA, Newbrun E, Greenspan JS, Hoover CI, Anderson JH. Immunologic observations in macaques with Shigella-associated periodontal disease. J Periodontal Res. 1983; 18(2):139–148. PMID: 6135769.

15. Fortman JD, Hewett TA, Bennett BT. Laboratory Nonhuman Primate. 2002. 1st ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press;p. 100–101.

16. Levine MM, Kotloff KL, Barry EM, Pasetti MF, Sztein MB. Clinical trials of Shigella vaccines: two steps forward and one step back on a long, hard road. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007; 5(7):540–553. PMID: 17558427.

17. Oaks EV, Turbyfill KR. Development and evaluation of a Shigella flexneri 2a and S. sonnei bivalent invasin complex (Invaplex) vaccine. Vaccine. 2006; 24(13):2290–2301. PMID: 16364513.

18. Passwell JH, Ashkenazi S, Harlev E, Miron D, Ramon R, Farzam N, Lerner-Geva L, Levi Y, Chu C, Shiloach J, Robbins JB, Schneerson R. Safety and immunogenicity of Shigella sonnei-CRM9 and Shigella flexneri type 2a-rEPAsucc conjugate vaccines in one- to four-year-old children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003; 22(8):701–706. PMID: 12913770.

19. Ranallo RT, Thakkar S, Chen Q, Venkatesan MM. Immunogenicity and characterization of WRSF2G11: a second generation live attenuated Shigella flexneri 2a vaccine strain. Vaccine. 2007; 25(12):2269–2278. PMID: 17229494.

20. Venkatesan MM, Ranallo RT. Live-attenuated Shigella vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2006; 5(5):669–686. PMID: 17181440.

21. Kaartinen L, Salonen M, Alli L, Pyörälä S. Pharmacokinetics of enrofloxacin after single intravenous, intramuscular and subcutaneous injections in lactating cows. J Vet Pharmacol Ther. 1995; 18(5):357–362. PMID: 8587154.

22. Aramayona JJ, Mora J, Fraile LJ, García MA, Abadía AR, Bregante MA. Penetration of enrofloxacin and ciprofloxacin into breast milk, and pharmacokinetics of the drugs in lactating rabbits and neonatal offspring. Am J Vet Res. 1996; 57(4):547–553. PMID: 8712523.

23. Klein H, Hasselschwert D, Handt L, Kastello M. A pharmacokinetic study of enrofloxacin and its active metabolite ciprofloxacin after oral and intramuscular dosing of enrofloxacin in rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta). J Med Primatol. 2008; 37(4):177–183. PMID: 18384536.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download