Abstract

Purpose

Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) is a disease that is primarily seen in adults and is comparatively rare in children. Consequently, only a few studies have focused on the pathogenesis of the disease in children. This study investigated the possible role of metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) in the pathogenesis of CSU in children.

Methods

The study group was composed of 54 children with CSU; 34 healthy children comprised the control group. The demographic and clinical features of the study group were extensively evaluated, and laboratory assessments were also performed. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was used to evaluate levels of plasma MMP-9. Disease activity was quantified using the urticaria activity score (UAS).

Results

The median value of plasma MMP-9 was 108.9 ng/mL (interquartile range, 93.3-124.1) in the CSU group and 87.8 ng/mL (69.4-103.0) in the control group. The difference between the 2 groups was statistically significant (P<0.001). Also, MMP-9 levels showed a significant positive correlation with UAS (rho=0.57, P<0.001). Twenty-six percent of patients had positive autologous serum skin test (ASST) results. Neither UAS nor plasma MMP-9 levels were significantly different between ASST-positive and -negative patients (P>0.05).

Chronic urticaria (CU) is defined as the persistence of an urticarial episode for at least 6 weeks.1 The prevalence of CU in children is one-tenth of that in adults (0.1% vs 1%).23 Autoimmune disorders, physical stimuli, infections, vasculitis, and allergies are the primary causes of CU. However, an underlying cause can only be identified in 20% to 55% of pediatric cases in spite of thorough clinical and laboratory investigations.45 CU is classified according to whether it is inducible or not into chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) or chronic inducible urticaria (CIU). CSU may be attributed to known or unknown causes.67

Matrix-metalloproteinases (MMPs) are a large family of zinc-dependent endopeptidases that can degrade many components of the extracellular matrix and other extracellular proteins.8 MMP-9 belongs to the gelatinase subfamily of MMPs and cleaves gelatin and type 4 collagen, which is the main component of the basement membrane. This cleavage helps inflammatory cells reach the site of inflammation.9 Additionally, MMPs can cleave proinflammatory chemokines, thereby regulating their functions and modulating inflammatory processes.1011 MMP-9 can be synthesized by many types of cells, including macrophages, neutrophils, T cells, and mast cells, and play a substantial role in autoimmune diseases, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and allergic diseases.91213

A few studies (with conflicting results) exist on the role of MMP-9 in the pathogenesis of CSU in adults; however, to our knowledge no studies have been performed in children. This study aims to clarify this topic.

Seventy-two consecutive patients who were referred between January and June of 2015 to the pediatric allergy outpatient clinics of 2 university hospitals (Istanbul University/Istanbul Medical Faculty and Bezmialem Vakif University) with the diagnosis of CSU were assessed for study eligibility. Patients who were diagnosed with CIU and whose potential causes of CU had been defined (except autoimmunity) were excluded. Diagnosis was based on the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology guidelines.6 None of the patients were taking corticosteroids, omalizumab, or immunosuppressive drugs. Detailed medical histories were obtained, and physical examinations were performed. Children with diseases that influence plasma MMP-9 levels, including concomitantly diagnosed asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, or other identified autoimmune disorders, were excluded from the study.91314 After exclusion, 54 patients with CSU were finally enrolled.

The control group included 34 healthy children who were periodically attending pediatric welfare clinics in the same hospitals for regular checkups. Children in the control group did not have a history of either acute or chronic urticaria, had never been diagnosed with any allergic disease, and were not taking any medications. Additionally, no signs of infectious disease were present in any of the subjects in the control group. The study was performed in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and good clinical practice, and was approved by the Bezmialem Vakif University Ethical Committee. All study patients and their parents were given information about the study, and signed consent was obtained from the parents.

Disease activity was evaluated by the same pediatric allergist using the urticaria activity score (UAS) according to the EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO Guidelines.15 UASs were calculated in interviews with patients and families as well as during physical examination. UAS consisted of the sum of the wheal number score and the pruritus score, which ranged from 0 to 6. The wheal numbers are graded as follows: 0, none; 1, Mild (<20 wheals/24 hours); 2, Moderate (20-50 wheals/24 hours); 3, Intense (>50 wheals/24 hours or large confluent areas of wheals). Moreover, the severity of itching is graded as follows: 0, none; 1, Mild (present but not annoying or troublesome); 2, Moderate (troublesome but does not interfere with normal daily activity or sleep); 3, Intense (severe pruritus, which is sufficiently troublesome to interfere with normal daily activity or sleep).15

Antihistamines and montelukast were discontinued at least 24 hours before blood sampling. After overnight fasting, peripheral blood samples (total, 4 mL) were collected from an antecubital vein into heparinized tubes; thereafter, blood was centrifuged at 1,500×g for 10 minutes to obtain the plasma. The separated plasma was stored at -80℃ until further analysis of MMP-9 levels.

For standard laboratory procedures, the following tests were obtained: thyroid-stimulating hormone, free thyroxin, anti-thyroid peroxidase and anti-thyroglobulin antibodies, liver function tests, complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, serum total immunoglobulin E (IgE), urinalysis with test strips and urine cultures, microscopic investigation of stool for parasites, and stool enzyme immunoassay for Helicobacter pylori antigen.

Skin prick tests and autologous serum skin tests (ASSTs) were also performed in the CSU group, but not for the control group. Commercial allergen solutions manufactured by Stallergenes (Paris, France) were used for skin prick tests. Among the test allergens were 10 different aeroallergens consisting of grass pollen mixture, Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, Dermatophagoides farinae, Alternaria, Aspergillus mixture, weed pollen mixture, birch, cypress, cat epithelia, dog epithelia, and 6 food allergens consisting of milk, egg white, egg yolk, peanut, wheat, and cocoa. Skin prick tests were considered positive with the presence of a wheal with at least 3-mm maximum diameter after subtraction of the negative value. ASST was performed using the method described by Sabroe et al.16 We were not able to perform skin prick tests and ASST on 8 patients because their antihistamine-containing medications could not be discontinued due to the intensity and severity of their symptoms.

Plasma levels of MMP-9 were assessed using a human MMP-9 enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Bender Med Systems, Vienna, Austria). Samples were thawed at room temperature and were then centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 minutes. Samples were diluted to obtain the appropriate concentrations, and an ELISA was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Supplied standards were used to generate standard curves. The samples and standards were added to the wells. Unbound protein was removed by washing, and conjugate was added. After a color reaction with a substrate, the optical density was recorded using an automated ELISA reader at a wavelength of 450 nm. The absorbance at 450 nm was converted to ng/mL for MMP-9. The minimal detection limit was 0.05 ng/mL for MMP-9.

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS 19 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test distributions for normality. Parametric data are expressed as the mean±standard deviation (SD), and non-parametric data are expressed as the median, interquartile range (IQR). The Mann-Whitney U test was used to calculate the differences in variables between groups. The correlation between 2 variables was assessed using the Spearman rank correlation coefficient. Categorical data were evaluated using the chi square test; P<0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

The CSU group consisted of 33 boys and 21 girls, and the control group consisted of 18 boys and 16 girls. The mean ages of the CSU and control group participants were 10.8±4.2 and 10.3±3.9 years, respectively. No significant differences in age or gender were present between the 2 groups (P>0.05). The median duration of disease was 13 months (7-23.3 months), and the median value of UAS was 4 (2-5). Some demographic and clinical features of the patients and the control subjects are shown in Table.

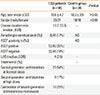

The median values of plasma MMP-9 were 108.9 ng/mL (93.3-124.1) in the CSU group and 87.8 ng/mL (69.4-103.0) in the control group. The difference between the 2 groups was statistically significant (P<0.001; Fig. 1). Additionally, plasma MMP-9 levels showed a significant positive correlation with UAS (rho=0.57, P<0.001; Fig. 2). We detected ASST positivity in 26% of CSU group patients; plasma MMP-9 levels were not different between patients with ASSTs positivity and those without (P>0.05).

Our results clearly showed that children with CSU had elevated MMP-9 levels compared to healthy control subjects and that plasma MMP-9 levels were positively correlated with disease activity. Although some studies exist that evaluate the plasma MMP-9 levels in adult patients with CSU, this is the first study that focuses on the pediatric age group. This focus is especially important because CSU is rare in children, and recommendations for its management and also because treatment in children are based on data obtained from studies conducted on adults.17 Even comprehensive guidelines written on this topic include little information about children.1615 Undoubtedly, it is not the proper approach to interpret children as "small adults."17 Therefore, further studies are needed that focus on children, so the necessity of adapting the experiences of adults with the disease (and with treatment) is lessened or eliminated.

The activity of CSU can be assessed both by the physician during the examination (UAS) or by patients measuring and documenting urticaria through 24-hour self-evaluation scores once daily for 7 days (UAS7).6 UAS7 includes full family-derived information and scores, and provides an overview of the overall activity of the disease. We preferred to use UAS in this study because we attempted to compare momentary activity scores and cytokine levels. In addition, we aimed to reduce the influence on scoring of subjective assessments provided by families as much as possible. Although UAS has some limitations, it is simple, widely accepted, and only validated for assessing the severity of CU.615

The exact pathogenesis of CSU is not well delineated. The presence of persistent activation of dermal mast cells is a hallmark of CSU pathogenesis, but the underlying mechanisms of mast cell activation are an enigma.118 Urticarial wheals are characterized by dermal edema, vasodilatation, and perivascular infiltrates comprising lymphocytes, monocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils.1819 Altered numbers and imbalanced cytokine production of T cells have also been reported in patients with CSU.2021

Kessel et al.22 first reported that adult patients with CU have elevated plasma MMP-9 levels compared to healthy subjects, besides the presence of a positive correlation between MMP-9 levels and UAS. They also demonstrated that the CD4+ T cells of these patients were highly activated, concluding that activated CD4+ T cells residing in urticarial lesions may cause dermal mast cell activation and MMP-9 secretion.22 Tedeschi et al.23 and Altricher et al.24 also reported elevated plasma MMP-9 levels in patients with CU compared to healthy subjects in their studies conducted in adults. Conversely, in study by Altricher et al. the authors stated that disease activity is not correlated with MMP-9 levels, and that MMP-9 should not to be used to monitor disease activity or the efficacy of treatment.24

Wheals, flares, and angioedema, which are characteristics of CSU, develop as a result of increased vascular permeability.25 The literature provides some evidence that the presence of MMPs leads to increased vascular permeability, primarily through the disruption of tight junction proteins.26 Furthermore, MMPs strongly induce leukocyte migration.27 These features of MMP-9 could explain some of the key points behind the pathogenesis of CSU. The therapeutic efficacy of MMP-9 activity inhibition is a highly active area of research in the treatment of cancer and ischemic strokes.2829 Several methods and drugs have been proposed for this purpose in the literature, including lentiviral-mediated MMP-9 gene silencing, MMP-9 neutralizing antibodies, recombinant tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases-1, gold nanoparticles, minocycline, and synthetic MMP inhibitors.2829 Therefore, MMP-9 seems not only to be a good biomarker of disease activity, but also to be a promising therapeutic target.

Plasma MMP-9 levels were elevated in pediatric patients with CSU and were positively correlated with the UAS. Therefore, MMP-9 seems to be both a good biomarker for disease activity and a promising therapeutic target. Several drugs and methods that can inhibit MMP-9 activity are described in the literature. Additionally, we emphasize that this is the first and only study conducted on children. We need further studies to say the last word on this subject.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 2

Correlation graphs between plasma matrix metalloprotease-9 (MMP-9) levels and urticaria activity scores (UASs) in patients with CSU.

Table

Some demographic and clinical features of the study and control groups

References

1. Powell RJ, Leech SC, Till S, Huber PA, Nasser SM, Clark AT. British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology. BSACI guideline for the management of chronic urticaria and angioedema. Clin Exp Allergy. 2015; 45:547–565.

2. Maurer M, Weller K, Bindslev-Jensen C, Giménez-Arnau A, Bousquet PJ, Bousquet J, et al. Unmet clinical needs in chronic spontaneous urticaria. A GA2LEN task force report. Allergy. 2011; 66:317–330.

3. Khakoo G, Sofianou-Katsoulis A, Perkin MR, Lack G. Clinical features and natural history of physical urticaria in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008; 19:363–366.

4. Volonakis M, Katsarou-Katsari A, Stratigos J. Etiologic factors in childhood chronic urticaria. Ann Allergy. 1992; 69:61–65.

5. Ghosh S, Kanwar AJ, Kaur S. Urticaria in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 1993; 10:107–110.

6. Zuberbier T, Aberer W, Asero R, Bindslev-Jensen C, Brzoza Z, Canonica GW, et al. The EAACI/GA(2) LEN/EDF/WAO guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria: the 2013 revision and update. Allergy. 2014; 69:868–887.

7. Vestergaard C, Deleuran M. Chronic spontaneous urticaria: latest developments in aetiology, diagnosis and therapy. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2015; 6:304–313.

8. Wells JM, Gaggar A, Blalock JE. MMP generated matrikines. Matrix Biol. 2015; 44-46:122–129.

9. Ram M, Sherer Y, Shoenfeld Y. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 and autoimmune diseases. J Clin Immunol. 2006; 26:299–307.

10. Van den Steen PE, Proost P, Wuyts A, Van Damme J, Opdenakker G. Neutrophil gelatinase B potentiates interleukin-8 tenfold by aminoterminal processing, whereas it degrades CTAP-III, PF-4, and GRO-alpha and leaves RANTES and MCP-2 intact. Blood. 2000; 96:2673–2681.

11. Song J, Wu C, Zhang X, Sorokin LM. In vivo processing of CXCL5 (LIX) by matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 and MMP-9 promotes early neutrophil recruitment in IL-1β-induced peritonitis. J Immunol. 2013; 190:401–410.

12. Yabluchanskiy A, Ma Y, Chiao YA, Lopez EF, Voorhees AP, Toba H, et al. Cardiac aging is initiated by matrix metalloproteinase-9-mediated endothelial dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014; 306:H1398–H1407.

13. Belleguic C, Corbel M, Germain N, Léna H, Boichot E, Delaval PH, et al. Increased release of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in the plasma of acute severe asthmatic patients. Clin Exp Allergy. 2002; 32:217–223.

14. Harper JI, Godwin H, Green A, Wilkes LE, Holden NJ, Moffatt M, et al. A study of matrix metalloproteinase expression and activity in atopic dermatitis using a novel skin wash sampling assay for functional biomarker analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2010; 162:397–403.

15. Zuberbier T, Asero R, Bindslev-Jensen C, Walter Canonica G, Church MK, Giménez-Arnau A, et al. EAACI/GA(2)LEN/EDF/WAO guideline: definition, classification and diagnosis of urticaria. Allergy. 2009; 64:1417–1426.

16. Sabroe RA, Grattan CE, Francis DM, Barr RM, Kobza Black A, Greaves MW. The autologous serum skin test: a screening test for autoantibodies in chronic idiopathic urticaria. Br J Dermatol. 1999; 140:446–452.

17. Church MK, Weller K, Stock P, Maurer M. Chronic spontaneous urticaria in children: itching for insight. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2011; 22:1–8.

18. Jain S. Pathogenesis of chronic urticaria: an overview. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014; 2014:674709.

19. Caproni M, Giomi B, Volpi W, Melani L, Schincaglia E, Macchia D, et al. Chronic idiopathic urticaria: infiltrating cells and related cytokines in autologous serum-induced wheals. Clin Immunol. 2005; 114:284–292.

20. Sun RS, Sui JF, Chen XH, Ran XZ, Yang ZF, Guan WD, et al. Detection of CD4+ CD25+ FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in peripheral blood of patients with chronic autoimmune urticaria. Australas J Dermatol. 2011; 52:e15–e18.

21. Dos Santos JC, Azor MH, Nojima VY, Lourenço FD, Prearo E, Maruta CW, et al. Increased circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines and imbalanced regulatory T-cell cytokines production in chronic idiopathic urticaria. Int Immunopharmacol. 2008; 8:1433–1440.

22. Kessel A, Bishara R, Amital A, Bamberger E, Sabo E, Grushko G, et al. Increased plasma levels of matrix metalloproteinase-9 are associated with the severity of chronic urticaria. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005; 35:221–225.

23. Tedeschi A, Asero R, Lorini M, Marzano AV, Cugno M. Plasma levels of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in chronic urticaria patients correlate with disease severity and C-reactive protein but not with circulating histamine-releasing factors. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010; 40:875–881.

24. Altrichter S, Boodstein N, Maurer M. Matrix metalloproteinase-9: a novel biomarker for monitoring disease activity in patients with chronic urticaria patients? Allergy. 2009; 64:652–656.

25. Carr TF, Saltoun CA. Chapter 21: urticaria and angioedema. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2012; 33:Suppl 1. S70–S72.

26. Bauer AT, Bürgers HF, Rabie T, Marti HH. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 mediates hypoxia-induced vascular leakage in the brain via tight junction rearrangement. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010; 30:837–848.

27. Song J, Wu C, Korpos E, Zhang X, Agrawal SM, Wang Y, et al. Focal MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity at the blood-brain barrier promotes chemokine-induced leukocyte migration. Cell Rep. 2015; 10:1040–1054.

28. Herszényi L, Hritz I, Lakatos G, Varga MZ, Tulassay Z. The behavior of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in colorectal cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2012; 13:13240–13263.

29. Chaturvedi M, Kaczmarek L. Mmp-9 inhibition: a therapeutic strategy in ischemic stroke. Mol Neurobiol. 2014; 49:563–573.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download