Abstract

Jeju is an island in South Korea located in a temperate climate zone. The Japanese cedar tree (JC) has become the dominant tree species while used widely to provide a windbreak for the tangerine orchard industry. An increase in pollen counts precedes atopic sensitization to pollen and pollinosis, but JC pollinosis in Jeju has never been studied. We investigated JC pollen counts, sensitization to JC pollen, and JC pollinosis. Participants were recruited among schoolchildren residing in Jeju City, the northern region (NR) and Seogwipo City, the southern region (SR) of the island. The JC pollen counts were monitored. Sensitization rates to common aeroallergens were evaluated by skin prick tests. Symptoms of pollinosis were surveyed. Among 1,225 schoolchildren (49.6% boys, median age 13 years), 566 (46.2%) were atopic. The rate of sensitization to Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus (35.8%) was highest, followed by D. farinae (26.2%), and JC pollen (17.6%). In the SR, 156 children (23.8%) were sensitized to JC pollen; this rate was significantly higher than that in the NR (59 children, 10.4%, P<0.001). A significant increment in the sensitization rate for JC pollen with increasing school level was observed only in the SR. JC pollen season in the SR started earlier and lasted longer than that in the NR. JC pollen season in Jeju was defined as extending from late January to mid-April. The prevalence of JC pollinosis was estimated to be 8.5%. The prevalence differed significantly between the NR and SR (5.3% vs 11.3%, P<0.001), mainly due to the difference in sensitization rates. JC pollen is the major outdoor allergen for early spring pollinosis in Jeju. JC pollen season is from late January to mid-April. Warmer weather during the flowering season scatters more JC pollen in the atmosphere, resulting in a higher sensitization rate in atopic individuals and, consequently, making JC pollinosis more prevalent.

Allergic inflammation in response to pollen antigens in the nasal airway causes pollinosis. Sneezing, coryza, stuffiness, and itching around the nose and eyes are evoked during the efflorescence. Repeated and extended exposure to pollen among atopic individuals is considered to precede atopic sensitization to pollen antigens.

Jeju is a province of South Korea, an island separated from the Korean peninsula.1 Because of its warm climate, tangerine orchards are one of the main industries. The Japanese cedar tree (Cryptomeria japonica, JC) was planted as a windbreak to decrease fruit loss. Because of systematic planting, JC became the dominant tree species. Jeju is the only province where JC pollen is detected in Korea,2 and as a result it has become the most common sensitizing outdoor allergen for Jeju residents.3,4 However, the prevalence of JC pollinosis has never been studied.

In Jeju, there are 2 city districts (Jeju City and Seogwipo City), only about 30 km north and south of each other. Although they are in the same climate zone, there is a natural temperature gradient between the cities.1 We investigated the JC pollen-sensitization-pollinosis and hypothesized that the climate difference might influence the prevalence of JC pollinosis among the residents in the 2 cities.

In Jeju, there are 2 school districts that correspond with the city districts. A balanced selection of schools and grades was made from each school district. The attendees of the schools located in Jeju City are representative of residents of Jeju City (northern region, NR), and those in Seogwipo City are of Seogwipo City (southern region, SR) (Fig. 1). All those students in the school year of 2010 were initially included.

The skin prick test was performed after informed consent from each student's parents. JC pollen (Greer Laboratories Inc., Lenoir, NC, USA) was diluted with 0.9% saline to a protein concentration of 100 µg/mL, and the same volume of 50% glycerin was added. Sensitization to an antigen was defined as a mean wheal size that was the same or larger than that of the positive control (allergen/histamine ratio ≥1). Atopy was defined as sensitization to one or more aeroallergens tested. The data were excluded when the wheal size for the positive control (histamine 1 mg/mL) was smaller than 2 mm or if a wheal was observed in the negative control (0.9% saline).

A questionnaire was designed, which asked whether pollinosis symptoms were present within the last 12 months and in which month they were present. A case of JC pollinosis was defined as one with pollinosis symptoms present during the JC efflorescence season among the JC pollen-sensitized.

Burkard 7-day recording volumetric spore traps (Burkard Manufacturing Co., Rickmansworth, UK) were installed in the 2 geographic locations of 126°31'13.67" E, 33°29'29.27" N, representative of the NR, and 126°33'18.97" E, 33°15'11.86" N, representative of the SR (Fig. 1). The drum in the device was harvested weekly at the same time. The trapped pollen was mounted in glycerin jelly and stained. The pollen collected per 24-hour period was identified and counted by an expert at ×400.

JC pollen season in each year was defined as extending from the first day when JC pollen was detected on 2 or more consecutive days to the first day when no JC pollen was identified for a full day.

Monthly mean temperature data for the two regions were obtained from the database of the Korea Meteorological Administration.5

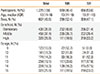

Among the 1,750 questionnaires distributed, 1,524 (87.1%) were returned. Skin prick tests were performed on 1,291 students (73.8%) in April 2010, and 1,225 participants with valid skin prick tests (607 boys, 49.6%, median age of 13, interquartile range [IQR] 11-16) were included in the final analysis. Among those, 438 (35.8%) were attending elementary school, 458 (37.4%), middle school, and 329 (26.9%), high school. Overall, 569 students (46.4%, boys 52.4%, median age 13, IQR 11-16) resided in the NR, and 656 (53.6%, boys 47.1%) resided in the SR (Table 1).

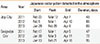

The sensitization rate was highest for house dust mites followed by JC pollen (17.6%). The participants from the SR showed a higher rate of atopy than those from the NR (50.6% vs. 41.1%, P<0.001). The sensitization rates for the individual aeroallergens, mold II, JC, pine, willow, and birch pollens were higher in the SR than in the NR (P<0.05, respectively) (Table 2).

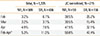

The sensitization rates for JC pollen were highest among the outdoor aeroallergens tested, and identical between sexes, but significantly increased with school grade (P=0.010). Those were significantly higher in the SR (156 sensitized, 23.8%) than in the NR (59, 10.4%) (P<0.001) (Table 3). According to their school level, a significant increment in the sensitization rate for JC pollen with age was observed only in participants from the SR (Fig. 2).

The JC pollen season was estimated from 2011 to 2013. In the SR, the JC pollen season lasted for 47 days in 2011, 72 in 2012, and 95 in 2013 in the SR, and in the NR for 43 days in 2011, 65 in 2012, and 65 in 2013 (Table 4). The JC pollen season started earlier and lasted longer in the SR than in the NR. For pollen counts measured on the peak days, the level of JC pollen in the atmosphere in the SR was estimated to be 2-8 times higher than that in the NR (Fig. 3). Despite the yearly variations, JC pollen season in Jeju can be considered from late January to mid-April.

Of 1,225 participants, 104 were sensitized to JC pollen and had symptoms of pollinosis in the JC pollen season in Jeju. The prevalence of JC pollinosis was estimated to be 8.5%. The prevalence differed significantly between the NR and SR (5.3% vs 11.3%, P<0.001). The difference was mainly related to the difference in sensitization rates in the 2 regions (Table 5).

During the JC pollen season, there was a difference in the mean temperature between the geographic regions. The mean temperature during the main efflorescence season for JC pollen was higher by 2.0℃ in February and by 1.9℃ in March in Seogwipo City than in Jeju City (Fig. 4).

Among several cities in Korea for which pollen counts are monitored, JC pollen is detected only in Jeju. Consequently, the sensitization rates for JC pollen are much higher (33.8%) in Jeju than in Seoul (1.1%) and Suwon (0.7%).4 JC pollen is the most frequent sensitizer among the outdoor aeroallergens found in Jeju.3,6

In Japan, JC pollinosis has been investigated in depth. Due to the systemic afforestation after World War II, JC pollen is the major allergen contributing to most prevalent seasonal allergic rhinitis.7,8,9 JC pollen triggers pollinosis more commonly than other pollens primarily because of its physical characteristics: a large amount of pollen is released, it disseminates further, and it stays longer in the air.9 In recent years, the amount of pollen in the atmosphere has increased, which is associated with an increase in sensitization rates with age.10 The prevalence of JC pollinosis has also been increasing, and as expected, is significantly correlated with the increment in sensitization rates.11 Up to one-third of the Japanese population suffers from JC pollinosis in early spring, and it is considered a national affliction in Japan.8

According to the recently updated calendar of allergenic pollen levels in Korea, pollens from birch, alder, pine, and juniper are also observed in early spring (February-March) in Jeju. The sensitization rates for these pollens, which were studied with a commercially available tree pollen mixture (alder, elm, hazel, poplar, willow, beech, birch, oak, and plane), were shown to be trivial,3 as we also showed in this study. The atmospheric concentrations of pollen other than JC pollen are expected to be relatively low3 because relatively fewer of these trees have been planted in Jeju.

The sensitization rate for JC pollen has been increasing year by year. In 1998, the sensitization rate for JC pollen was 9.7%,12 which rose to 18.2% in 2008,3 17.6% in 2010, and 24.4% in 2013 among schoolchildren in Jeju (unpublished data from the Environmental Health Center). Undoubtedly, the pattern of sensitisensitization is following that seen in Japan. In this study, the sensitization rate to JC pollen increased with age and school grade. There could be 2 opposite explanations for a higher sensitization rate in the older inhabitants of a geographic region, presuming no mass influx in population. First, a longer environmental exposure to an allergen may make atopic individuals more likely to be sensitized with increasing age, so sensitization could be cumulative. Alternatively, a recent decrease in the level of an allergen in the environment could result in less frequent sensitization in the younger population.

In Jeju, the sensitization rates for only some pollens increased with participant age. The sensitization rate for Japanese hop pollen and early flowering trees actually decreased with age.3 The rate of sensitization to JC among schoolchildren in Jeju has undoubtedly increased over time, and as postulated above, a higher rate of sensitization in the older participants might be related to their longer cumulative environmental exposure to pollen. Interestingly, the age-related increment in sensitization was observed in the Seogwipo City residents, but not in the Jeju City residents. This could be related to the difference in climate between the 2 geographical regions.

Why is the rate of sensitization to JC pollen increasing? Roles are hypothesized for global climate change, forest growth, or air pollutants.13 There may be 2 ways that global climate change could influence human health: an indirect effect by increasing the average temperature, and a direct effect caused by CO2-induced stimulation of photosynthesis and plant growth.14,15 Warmer weather evokes earlier flowering, more effective pollen scattering in the air, and a prolonged efflorescence season.16,17,18 Monitoring has shown an increasing mean temperature in Jeju since 1990.19 The temperature gradient in early spring between the 2 regions, although they are just 30 km apart, might be caused by the different ocean currents and the effect of Halla Mountain (1,950 meters above sea level), situated between them. The results of the current study support the hypothesis that any global warming, especially in the flowering season, might increase further the rate of sensitization to JC pollen in future, which results in a greater prevalence of pollinosis.

A population-based prevalence of pollinosis to a specific pollen is difficult to estimate without mass provocation testing with the pollen. Although changes in sensitization rate and prevalence correlate significantly,11 a cross-sectional study found that the sensitization rate is not the same as the prevalence due to the presence of asymptomatic sensitized individuals. In this study, the population-based prevalence of JC pollinosis was estimated on the basis of the number of JC pollen sensitized individuals who had rhinitis symptoms in early spring. The proportion of pollinosis evoked by pollens other than JC pollen seems to be negligible due to the markedly lower concentration of and lower sensitization rate to other pollen.2,3 The prevalence of symptomatic JC pollinosis is estimated to be half that of JC pollen sensitization, regardless of the residential region, which is a figure that can be applied in future studies.

There are some limitations to this study. Climatic variables other than temperature, such as wind speed, wind direction, and precipitation during the efflorescence season, might influence the pollen counts. Higher rainfall or higher humidity is considered to have a negative effect on pollen scattering. Finally, we can suggest no explanation as to why increasing sensitization rates with age were observed only in the Seogwipo City residents. Sequential monitoring should provide an answer.

In conclusion, JC pollen is the major outdoor allergen that causes early spring pollinosis in Jeju. The JC pollen season is from late January to mid-April. Warmer weather during the flowering season scatters more JC pollen in the atmosphere, resulting in more sensitization in atopic individuals, and as a consequence, making JC pollinosis more prevalent. This is the first study addressing the relationship between pollen counts, sensitization rate, and the prevalence of JC pollinosis in Jeju, Korea.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

(A) A geographical scheme of the study. The white arrow indicates Jeju island in South Korea. (B) The approximate geographical locations of the selected schools (circles) and the pollen counters (white stars) are marked.

Fig. 2

The sensitization rate to Japanese cedar pollen by residential areas and schools attended. Numbers indicate proportions (%). *P=0.839; **P=0.029.

Fig. 3

The actual counts of Japanese cedar pollen collected in Jeju City (A) and Seogwipo City (B) from 2011 (upper)-2013 (lower).

Fig. 4

The monthly mean temperature during Japanese cedar efflorescence season in Jeju City and Seogwipo City.

Table 1

Demographic characteristics

Table 2

Sensitization rates to common aeroallergens

Table 3

Characteristics of the 215 participants sensitized to Japanese cedar pollen

Table 4

Japanese cedar pollen season in Jeju

Table 5

The prevalence of Japanese cedar pollinosis in Jeju, estimated by the presence of pollinosis symptoms during the pollen season

| Total, N=1,225 | JC sensitized, N=215 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NR, N=569 | SR, N=656 | NR, N=59 | SR, N=156 | |

| Feb | 3.2% | 6.7% | 30.5% | 28.2% |

| Mar | 3.2% | 3.7% | 30.5% | 15.4% |

| Apr | 4.9% | 7.6% | 47.5% | 32.1% |

| Feb-Apr* | 5.3% | 11.3% | 50.8% | 47.4% |

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by a research grant from the Environmental Health Center (Atopic Dermatitis & Allergic Rhinitis) at Jeju National University School of Medicine, Jeju, Korea.

References

1. Jeju Special Self-Governing Province (KR). [Internet]. Jeju: Jeju Special Self-governing Province;2007. cited 2014 Dec 1. Available from: http://english.jeju.go.kr/.

2. Oh JW, Lee HB, Kang IJ, Kim SW, Park KS, Kook MH, et al. The revised edition of Korean calendar for allergenic pollens. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2012; 4:5–11.

3. Jeon BH, Lee J, Kim JH, Kim JW, Lee HS, Lee KH. Atopy and sensitization rates to aeroallergens in children and teenagers in Jeju, Korea. Korean J Asthma Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010; 30:14–20.

4. Kim TB, Kim KM, Kim SH, Kang HR, Chang YS, Kim CW, et al. Sensitization rates for inhalant allergens in Korea; a multi-center study. J Asthma Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003; 23:483–493.

5. Korea Meteorological Administration. [Internet]. Seoul: Korea Meteorological Administration;2013. cited 2014 Dec 1. Available from: http://www.kma.go.kr/.

6. Lee HS, Hong SC, Kim SY, Lee KH, Kim JW, Kim JH, et al. The Influence of the residential environment on the sensitization rates to aeroallergens and the prevalence of allergic disorders in the school children in Jeju. Pediatr Allergy Respir Dis. 2011; 21:176–185.

7. Honda K, Saito H, Fukui N, Ito E, Ishikawa K. The relationship between pollen count levels and prevalence of Japanese cedar pollinosis in Northeast Japan. Allergol Int. 2013; 62:375–380.

8. Kanazawa A, Terada T, Ozasa K, Hyo S, Araki N, Kawata R, et al. Continuous 6-year follow-up study of sensitization to Japanese cedar pollen and onset in schoolchildren. Allergol Int. 2014; 63:95–101.

9. Okamoto Y, Horiguchi S, Yamamoto H, Yonekura S, Hanazawa T. Present situation of cedar pollinosis in Japan and its immune responses. Allergol Int. 2009; 58:155–162.

10. Ozasa K, Hama T, Dejima K, Watanabe Y, Hyo S, Terada T, et al. A 13-year study of Japanese cedar pollinosis in Japanese schoolchildren. Allergol Int. 2008; 57:175–180.

11. Kaneko Y, Motohashi Y, Nakamura H, Endo T, Eboshida A. Increasing prevalence of Japanese cedar pollinosis: a meta-regression analysis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2005; 136:365–371.

12. Min KU, Kim YK, Jang YS, Jung JW, Bahn JW, Lee BJ, et al. Prevalence of allergic rhinitis and its causative allergens in people in rural area of Cheju island. J Asthma Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999; 19:42–49.

13. Yamada T, Saito H, Fujieda S. Present state of Japanese cedar pollinosis: the national affliction. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014; 133:632–639.

14. Interagency Working Group on Climate Change and Health. A human health perspective on climate change: a report outlining the research needs on the human health effects of climate change. Research Triangle Park, NC: Environmental Health Perspectives/National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences;2010.

15. Stitt M. Rising CO2 levels and their potential significance for carbon flow in photosynthetic cells. Plant Cell Environ. 1991; 14:741–762.

16. Beggs PJ. Impacts of climate change on aeroallergens: past and future. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004; 34:1507–1513.

17. van Vliet AJ, Overeem A, De Groot RS, Jacobs AF, Spieksma FT. The influence of temperature and climate change on the timing of pollen release in the Netherlands. Int J Climatol. 2002; 22:1757–1767.

18. Teranishi H, Katoh T, Kenda K, Hayashi S. Global warming and the earlier start of the Japanese-cedar (Cryptomeria japonica) pollen season in Toyama, Japan. Aerobiologia. 2006; 22:90–94.

19. Lee SH, Nam KW, Jeong JY, Yoo SJ, Koh YS, Lee S, et al. The effects of climate change and globalization on mosquito vectors: evidence from Jeju island, South Korea on the potential for Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) influxes and survival from Vietnam rather than Japan. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e68512.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download