Abstract

Purpose

Methods

Results

Conclusions

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Study flow and subject disposition. A total of 258 subjects aged ≥18 years successfully completed the study. Subjects were randomly assigned to treatment groups receiving 200 µg ciclesonide nasal spray, 5 mg oral levocetirizine, or a combination of both.

Fig. 2

Changes in efficacy parameters. Analysis of symptom severity was conducted using reflective total nasal symptom score (rTNSS) values recorded in patient diaries and averaged over the 2-week period. The rTNSS was calculated as the sum of four nasal symptoms: rhinorrhea, nasal itching, nasal congestion, and sneezing, each of which was rated on a scale of 0 (no signs/symptoms evident) to 3 (signs/symptoms causing significant discomfort that interfered with daily activities) for the full analysis set (FAS) population. The Reflective total ocular symptom score (rTOSS) was calculated as the sum of three ocular symptoms: itchy eyes, red eyes, and watery eyes, each rated on a scale of 0 (no signs/symptoms evident) to 3 (signs/symptoms causing significant discomfort that interfered with daily activities). physician-assessed overall nasal signs and symptoms severity (PANS) values were obtained from the investigators assessments of nasal signs (discoloration, swelling, discharge, and postnasal drip) and symptoms (rhinorrhea, itching, nasal congestion, and sneezing). Rhinoconjunctivitis quality-of-life questionnaires (RQLQ) was obtained via patient self-assessment of the 28 listed items. SD, standard deviation.

Fig. 3

Changes in efficacy parameters. Analysis of symptom severity was conducted using rTNSS (reflective total nasal symptom score) values recorded in patient diaries and averaged over the 2-week period. The rTNSS was calculated as the sum of four nasal symptoms: rhinorrhea, nasal itching, nasal congestion, and sneezing, each of which was rated on a scale of 0 (no signs/symptoms evident) to 3 (signs/symptoms causing significant discomfort that interfered with daily activities) for the full analysis set (FAS) population. The P values shown in the figure measure statistical significance between C (ciclesonide) vs L (levocitirizine) vs C+L (combination treatment) groups at P<0.05 through ANOVA. The P value for rhinorrhea was 0.0388, for itching 0.0429, for nasal congestion 0.0202, and for sneezing 0.4014. If a P value indicated statistical significance at P<0.05 within a scoring system, additional comparative analyses were performed in order to clarify which groups were responsible for the significance. Significant comparisons at the 0.05 level are indicated by asterisks (*) through multiple comparison analysis by Fisher's Least Significance Difference (LSD). Whiskers to the bars indicate SEM.

Fig. 4

Correlation analysis between rTNSS and PANS. Exploratory analysis for the correlation of rTNSS and PANS was conducted using Pearson's correlation analysis.

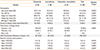

Table 1

Patient Characteristics (FAS)

*ANOVA; †Fisher's exact test; ‡Chi-square test.

FAS, full analysis set; SD, standard deviation; BMI, body-mass Index; ARIA, allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma; rTNSS, reflective total nasal symptom score; rTOSS, reflective total ocular symptom score; PANS, physician-assessed overall nasal signs and symptoms severit; RQLQ, rhinoconjunctivitis quality-of-life questionnaires.

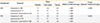

Table 2

Subgroup analysis by allergic rhinitis classification-change in rTNSS before and after treatment (FAS)

*P value by Paired t test; †P value by ANOVA; ‡Data entry for one subject failed to clarify whether the subject had SAR or PAR, so they were excluded from this analysis. FAS, full analysis set; rTNSS, reflective total nasal symptom score; SAR, seasonal allergic rhinitis; PAR, perennial allergic rhinitis.

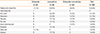

Table 3

Adverse drug reactions, of which a causal relationship with treatment could not be ruled out (Safety Analysis Set)

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download